RKUL: Time Well Spent, 11/27/2025

Gratitude edition

Your time is finite. Your phone and the internet stand ready to help you squander it. Here are my latest picks for spending it well instead. Feel free to add more in the comments.

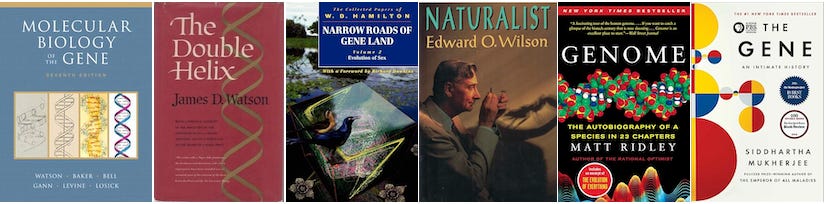

Books, what else?

James Watson died on November 6th, 2025. Born in 1928, in his 97 years, he witnessed sea changes in culture, technology and of course science. Along with Francis Crick, he puzzled out the structure of DNA, the substrate of genetic inheritance. He, Crick and Maurice H. F. Wilkins shared the 1962 Nobel Prize in Medicine for that discovery. Watson was no one-trick pony; appointed director of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in 1968, he transformed it into one of America’s premier centers of biological discovery, steering it past its eugenicist past. In 1990, Watson helmed the Human Genome Project, departing after two years over a disagreement concerning gene patents. In 2013, the Supreme Court invalidated the concept of gene patents, coming down on the side Watson (and most geneticists, frankly) had always favored.

Americans had many reasons to know Watson better than Crick. First, and foremost, Watson was American, while Crick was English (though after 1977 Crick moved to the US from Cambridge, England. There, until his death in 2004,Crick devoted 30 years of his scientific career to neuroscience and understanding consciousness). Second, Watson was a more voluble, flamboyant and provocative figure than the more focused Crick. But perhaps most importantly, Watson wrote a scientific autobiography of their Nobel-prize winning discovery, The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA. The Double Helix, a personal memoir, presented Watson’s particular perspective on how he and Crick discovered the structure of DNA. The book has gone through 213 printings in various editions and languages across the world, capped off by 2012’s Annotated and Illustrated Double Helix. People have faulted Watson’s narrative in various ways, most prominently for giving short shrift to Rosalind Franklin’s contributions, but it remains the definitive account of DNA’s discovery and the prose captures the excitement of biological science in a post-war England then just springing back to life and normalcy. If you want to understand how scientists came to grasp DNA’s structure, The Double Helix there is no better place to start, even acknowledging that it is not the entire story.

If Watson’s authorship of The Double Helix established his reputation and public stature, it was 1965’s The Molecular Biology of the Gene that most influenced working scientists and biology students. The elucidation of genetics’ physical mechanics, as opposed to observation of statistical regularities within pedigrees, revolutionized the field and established the foundation of contemporary molecular biology. Understanding DNA as a biological machine allowed researchers to re-conceptualize as biophysical processes abstractions like recombination and mutation, previously only inferred via patterns of traits transmitted through breeding lineages. And once genetics became a biophysical science, the methods of instrumentation and analysis could focus on its material variation in ways that paved the way for genomics’ advent. Genomics was stillborn, and the human genome could not have been mapped completely, until genetics became a molecular-biological discipline. It was Watson’s focus on establishing heredity’s physical basis that unlocked the key to the emergence of genomics, which in turn brought big data to genetic inference.

Not unlike James Watson, E. O. Wilson gained fame among the general public for his popular works and scientific controversies, from Sociobiology to his conflict with Harvard colleagues Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin. But before Wilson’s clashes with his left-wing peers in the department of Organismic Biology at Harvard, he had had tussles with a brash young James Watson in the 1950s. In Naturalist, Wilson’s autobiography, he relates how the co-discoverer of DNA had little use for traditional fields like taxonomy and anatomy, dismissing them as the domains of “stamp collectors.” The Watson-Wilson dispute in the 1950s prefigured the eventual fissure of Harvard’s biologists into molecular and non-molecular factions (this bifurcation is actually now very common in American science). But Naturalist clarifies that the dispute was personal too; Watson was egotistical, bold and vocal, Wilson more soft-spoken, if nevertheless quietly self-assured.

Near the end of their lives, Watson and Wilson reconciled on personal terms, developing a friendship based on a shared fascination with biology’s power to explain the world around them and a tendency towards heterodox, and often incendiary pronouncements. Watson famously got in hot water in 2007 for asserting that the black-white IQ gap likely has a genetic basis. Wilson was never canceled on account of such topics, but it has become clear looking at his correspondence and talking to those who knew him that he held much the same views as Watson. But unlike DNA’s co-discoverer, the more prudent Wilson shared those opinions solely with intimates (Francis Crick’s personal correspondence makes it clear that Wilson also took Arthur Jensen’s side in the Jensen controversy).

The general public knew Watson and Wilson well during their lifetimes via their popular works. In contrast, W. D. Hamilton’s substantial oeuvre was known almost solely to scientists during his life, though after his 2000 death from malaria contracted during fieldwork Richard Dawkins eulogized him as the “most distinguished Darwinian since Darwin.” Hamilton’s ideas appear in most of Dawkins’ published works, as well as in Matt Ridley’s The Red Queen and The Origins of Virtue, but it is Hamilton’s volume 2 of his collected papers, Narrow Roads of Gene Land: Evolution of Sex, where he steps outside the narrower confines of science and comes alive as a human figure. Volume 2 of Narrow Roads of Gene Land was at a draft stage when Hamilton died, so his editors were powerless to force revisions that might have reduced its length and candor. It is true that Hamilton’s collected papers have overly indulgent introductions, are larded with biographical detail and myriad meandering asides, but it is in volume 2 that you can most easily discern the awkward and sensitive scholar described in other works like Ullica Segerstrale’s Nature’s Oracle: The Life and Work of W. D. Hamilton. Hamilton occupies a strange and gray space between Watson and Wilson, though his life paralleled that of the two American biologists. Hamilton, an evolutionary geneticist steeped in the mathematical formalism of R. A. Fisher and, in his leisure an enthusiastic naturalist in the British tradition, saw little to be gained from embracing Watson’s molecular reductionism. But unlike Wilson, Hamilton was an evolutionary reductionist, working out complex and abstruse mathematical theories that would offer conceptual scaffolding to generations of empirical biologists. Though never entirely convinced of their completeness, Wilson describes encountering Hamilton’s ideas of inclusiveness in the 1960s in a scales-falling from his eyes moment that would eventually lead him to write Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.

More recently, Matt Ridley’s 1999 book Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters, inspired a generation of geneticists to enter the field, while Siddhartha Mukherjee’s 2016 The Gene: An Intimate History gives a flavor of the field midway through its plunge deep into the genomic era. Genome was written at the tail end of the Human Genome Project, so though it anticipates questions like the number of genes to be found in the human genome; those details remained to be finalized at the time. Ridley’s book also came out before the genome-wide association era, and so includes no discussion of the surfeit of post-2005discoveries. Nevertheless, Genome already satisfyingly establishes the superstructure of genetics as it was to be understood in the first 25 years of the 21st century.

Mukherjee’s The Gene came out after the publication of the human genome, and the widespread deployment of genomic technologies toward understanding classical genetic questions. The Gene was also written four years into the CRISPR gene-editing revolution, and so could anticipate the probable future of writing-in-the-genome that will likely follow close upon reading-the-genome’s advent. Though Mukherjee reviews Mendelism’s historical origins, as a medical doctor, he is more interested in genetics’ practical applications to ameliorate human suffering. While Genome seems to reflect more of the evolutionary curiosities of British geneticists like W. D. Hamilton, The Gene favors Watson’s more hard-headed reductionist perspective with the aim of vanquishing the ailments that have plagued humanity for all of its history.

Thought

Two Hundred Years to Flatten the Curve. Charles C. Mann writes in The New Atlantis about how public health has transformed our lives. The US in particular took public health seriously beginning in the late 19th century because of the waves of immigration from Europe whom native-born Americans believed arrived bearing disease. This resulted in a public health push that arguably rendered the US world’s first society to drive urban infant mortality rates lower than rural ones.

Mamdani’s biggest challenges. The headquarters of the global capital, New York City, is now going to be governed by a man who is on record expressing deep misgivings about capitalism. As Noah Smith notes, finance powers New York City’s fiscal health, but this is the same sector that Zohran Mamdani and his fellow travelers are most suspicious of.

The Sierra Club Embraced Social Justice. Then It Tore Itself Apart. The organization seems to have lost sight of why people donate to it. We’ve come a long way from, “The mountains are calling and I must go” to “One of the staff said, ‘That’s fine, Delia. But what do wolves have to do with equity, justice and inclusion?’”

The dirty secret of the Muslim world: The neglect of the history of Islamic slavery reflects a culture of American exceptionalism and a tradition of denial. This is just plain ignorance or intellectual dishonesty that it is a “dirty secret”; anyone who has read Islamic history even casually knows that sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Central Asia were the hunting grounds of Muslim slavers.

China Started Separating Its Economy From the West Years Ago. They are ready for the trade war because they have been preparing for it.

Data

Estimation and mapping of the missing heritability of human phenotypes. Blockbuster paper that surveys what we know from the UK Biobank about the heritability of phenotypes as understood through genomics.

Revisiting the Evolution of Lactase Persistence: Insights from South Asian Genomes. As in Europeans, it looks like there are some late (as recent as 1,000 years ago) selection events increasing the frequency of lactase persistence in the Indian subcontinent, though most of the variation in frequency across populations is a function of steppe ancestry.

Post-admixture selection favours Duffy negativity in the Lower Okavango Basin. Malaria has reshaped the genomes of Africans. First among these were agricultural populations, but these findings show that the same dynamic occurs with Khoisan people who mix advantageously with Bantus and invade the malarial zone.

The persistence and loss of hard selective sweeps amid ancient human admixture. Using deep learning on ancient genomes to reconstruct classical evolutionary dynamics that poor data quality and demographic phenomena like population bottlenecks might otherwise obscure.

My Two Cents

There’s still no free lunch, free subscribers; my most in-depth pieces for this Substack remain beyond the paywall. Most recently, I delved into the genetics of successive waves of Greenland settlers and the recent publication of a second high-coverage Denisovan genome.

First, The cave where it happened: Denisova cavern’s congress of ancient peoples:

Although we now have genetic material from many more than a single Denisovan (for example, mitochondrial DNA from 10 individuals), because all the other samples have been comparatively incomplete, for paleogeneticists the high-quality whole genome from 2010 has continued to do the load-bearing work. This is the individual we call Denisova 3, sequenced at 30-fold coverage, meaning geneticists have sampled each region of her genome about thirty times to assure themselves of the accuracy of each position’s precise read. Not only is this excellent if we want to undertake deep evolutionary genomic analysis, it is modern medicine’s gold standard for medical-grade genetic inference (insurance companies traditionally require 30-fold coverage for whole-genome tests). Despite finding further fossils, attaining what they call environmental DNA (from debris where the group lived rather than even trace identifiable human remains) and snippets of sequence here and there from other Denisovans, the bulk of our genomic understanding of these enigmatic humans over the last 15 years has remained the legacy of Denisova 3. Until today.

Finally, at the end of 2025, a preprint reports a new high-quality whole-genome sequence, at 24-fold coverage: A high-coverage genome from a 200,000-year-old Denisovan. Though researchers found this individual, Denisova 25, at the same location, he is vastly older than Denisova 3, who died 65,000 years ago. Not only does this allow geneticists to probe deeper into the past (the rough estimate is that a staggering 5,400 generations separate Denisovan 25 from Denisova 3!), it finally allows for comparative genomic analyses, apples-to-apples high-quality genome to high-quality genome.

Denisovan 25 has already yielded fresh insights, from further confirmation of the carryover of pre-Denisovan humans into their lineage (and so ultimately, into parts of ours), to refinements in the understanding of Denisovan population structure and the timing of admixtures. The sequencing of a new Denisovan might not be as field-altering as the species’ 2010 discovery, but in 2025 we can say we are truly getting to grips with this people; we can now discern how many races they subdivided into, how many distinct times they mixed with different modern human populations and even the lineaments of their mysterious interactions among even more ancient and barely understood human lineages that preceded them into Asia.

Land acknowledgement, Greenland edition:

The Saga of the Greenlanders is a tale of daring and high adventure in strange and bleak landscapes. Texts went silent after 1408, while the archaeological record, with its paucity of material goods after 1300 and evidence of stress and dietary changes in some of the later remains, points to their saga’s final chapter closing not in triumph but sad, grinding defeat. Genetics confirms the medieval Norse left no long-term imprint on modern Greenlanders. Greenlanders today carry small amounts of ancestry from recent Danish male adventurers, but descend in the main from the Thule, the whale-hunters who swept so successfully across the Arctic. But the Saqqaq genome also shows that the Dorset suffered the same fate as the Norse, withering in their last centuries in the face of Thule expansion, even abandoning southern Greenland nearly a millennium before the Norse arrived. The parallel trajectories of these two groups, western and eastern, North American and European, show how the Thule were the exception. The Thule could withstand (and even flourish in) the most extreme climates that our species faced. From Neanderthals to Ancient North Eurasians, archaeology and genetics tell us that northern peoples have always teetered on the edge of existence, with the elements themselves an implacable enemy arrayed against their survival. The Norse were not exceptional failures, unable to adapt; rather, they faced the same formidable challenges of innumerable cultures that have pushed the northern limits of human occupation, going back nearly a million years. The centuries-long occupation of the Western and Eastern Settlements by the medieval Norse was simply the last of many failed attempts by humans of every stripe, all later to be overshadowed by the exceptional skills and talents of the Thule people in harnessing the resources of the north. In the end, the Norse defeat turns out to have actually been a footnote in someone else’s grand saga, a story of incredible resilience and outsized success, the tale of the Thule.

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club

A 2025 feature for paying subscribers, the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club briskly reviews notable new papers or preprints. At the end of each edition, I invite subscribers to vote on papers/preprints for future editions.

Most recently, Ghost Population in the Machine: AI finds Out-of-Africa plot twists in Papuan DNA:

Papuans, in their splendid isolation, might seem to be of little interest to the broader narrative of human evolution and genetic history, but it is their very distance from the migrations and the rise and fall of empires that renders them notable. Until recently, New Guinea seems to only have ever been occupied by the first modern humans to settle the island, with nothing beyond minor changes upon Austronesians’ arrival to its shores 3,000 years ago. But in 2010 New Guinea and Papuans were suddenly thrust to the center of human evolutionary discoveries. In that year, researchers discovered upon sequencing that the genome from Denisova cave in Siberia matched about 5% of the New Guinean people’s ancestry (and almost none outside of Australasia). Then, in 2016, other researchers examining Papuan whole genomes concluded that the people might also harbor ancestry from an earlier out-of-Africa migration than the well-characterized expansion 50,000 years ago that swept from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Previous editions:

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Homo with a side of sapiens: the brainy silent partner we co-opted 300,000 years ago

Brave new human: counting up the de novo mutations you alone carry

The wandering Fulani: children of the Green Sahara

Genghis Khan, the Golden Horde and an 842-year-old paternity test

For free subscribers: a sense of the format from my coverage of two favorite papers last year:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Discussion

All my podcasts go ungated two weeks after their Substack release. So I encourage subscribers on the free plan who’d like to automatically get them to subscribe to that podcast stream (Apple, Stitcher, and Spotify). If you want to listen on YouTube, please subscribe.

Here are podcasts since the last Time Well Spent:

ICYMI

My own domain also has all my links and updates: https://www.razib.com

, including links to the few different podcasts I’ve contributed to or run, my total RSS feed, and my more mainstream or print articles when I remember to post them, my Twitter, the occasional guest appearance, etc.

DM me

Facebook message me

Some of my past pieces for Palladium Magazine, The New York Times, Slate, Quillette and Nautilus.

Over to you

Comments are open to all for this post, so if you have more reading/listening suggestions or tips on who I should be talking to or what you’ve been waiting to read about, put them here.