Genghis Khan, the Golden Horde and an 842-year-old paternity test

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #7

This year I’m trying out an occasional feature for paying subscribers, the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club where I offer a brisk review and consideration of an interesting paper in human population genomics.

In the spirit of a conventional journal club, after each post, interested subscribers can vote on papers for future editions. I’m open both to covering the latest papers/preprints and reflecting back on seminal publications from across these first decades of the genomic era.

If your lab has work we might like or you otherwise want to suggest a paper for me to cover, feel free to respond to this email or comment on this post.

The previous editions are:

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Homo with a side of sapiens: the brainy silent partner we co-opted 300,000 years ago

Brave new human: counting up the de novo mutations you alone carry

The wandering Fulani: children of the Green Sahara

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #7

Today we’re reviewing a recent preprint that actually has bearing on an open question in Central Asian history: Genomes of the Golden Horde Elites and their Implications for the Rulers of the Mongol Empire (2025). It comes out of Naruya Saitou’s group at National Institute of Genetics, Mishima, Japan, and appeared on BioRxiv on June 17th, 2025. The first author is Ayken Askapuli, Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The rise of Tatary

In 1697, Peter the Great became the first Tsar in a century to leave Russia. He traveled incognito to Western Europe to see how the more advanced continental nations ran their affairs. Since the Tsar was 6 foot 8 (over 2 meters), his identity was an open secret in the nations where he traveled. The “Grand Embassy,” as the mission was called, is more important as an historical marker than an actual fact-finding foray for the way it illustrates the new Tsar’s desire to reorient Russia towards the west. Thus began the centuries-long internal debate between Westernizers and Slavophiles about whether their nation should orient itself toward the West or continue to identify as the core of a separate civilization, the two wolves within the Russian soul that continue to grapple to this day.

For most, Peter the Great is an exemplar of the handful of famous Russian rulers who demanded that their subjects join the community of European nations, as opposed to viewing themselves as a civilization apart, liminal between the East and West. The Tsar reputedly even demanded that his nation’s cartographers include European Russia in any maps nominally of the European continent. But in his own genealogy he exemplified the Russian people’s complex antecedents, and in particular its ruling class. As a Romanov, on his paternal line, Peter descended from conventional Russian nobility. But the Tsar’s mother, on the other hand, had a more exotic background; Natalya Naryshkina was from a family of nobles descended from a 15th-century Crimean Tatar named Mordko Kurbat Naryshko. His descendants, the House of Naryshkin, accepted Orthodox Christianity, and so were fully integrated into the Russian aristocracy. The old Western European quip that Russians were just Tatars if you scratched the surface was not entirely wrong about its ruling class, even for most Western-oriented members like Peter.

To begin to wrap your mind around Russia, it helps to go back to Kievan Rus, and Vladimir the Great’s 988 AD conversion to Christianity, which marked the heretofore backward and tribal peoples of Europe’s far eastern fringe’s entrée into civilization. Kievan Rus became Christian Europe’s bulwark against the various Turkic people menacing the continent, the last outpost of the civilization that saw itself as heir to Rome. But Peter’s Russia was not purely a product of Kievan Rus, whose rulers intermarried with the reigning dynasties of early medieval England, Norway and France.

But to really understand its history, culture and even its elite, recall that for centuries the Russian principalities were extensions of the empires of the steppe, subject to the powers that ruled the lands Westerners called Tatary. Though the term Tsar of all the Russians has Classical roots in the title Caesar, the Russian rulers only took up that mantle in 1547, centuries after the formative experience of the Grand Princes of Moscow, as vassals to rulers of the Golden Horde, the territory ruled by the descendents of Genghis Khan’s eldest son, Jochi. What the Russians term the “Tatar Yoke,” the period between the mid-13th and mid-15th centuries during which their rulers were subordinate to and paid tribute to Jochi’s descendants, transformed Russia from a state on Europe’s eastern edge, to a civilization intent on spanning Eurasia from the Baltic to Siberia.

But the Golden Horde was not just some bit player in Russia’s historiography. It was for centuries at the heart of affairs all across Eurasia, playing a central role in the politics of Iran and the Levant, supplying the manpower that made Egypt’s Mamelukes a formidable military power at the nexus of Africa and Asia, and guarding over the Silk Road trade routes that would tie China to Europe.

When Genghis Khan divided his domains before his death, bequeathing Jochi the territory that became the Golden Horde, vast, empty lands stretching from Siberia to the fringes of Central Europe, the terms of distribution seemed almost a punishment. A possible explanation for this was always the lingering cloud over his first-born’s paternity; Genghis Khan’s wife Bortai was kidnapped by the Merkid tribe, when he was leader of a Mongol faction. This was revenge: Genghis Khan’s own father had kidnapped his mother, Hoelun from her Merkid husband. During her captivity, Bortai was given in marriage to the younger brother of Hoelun’s original husband, and nine months after her kidnapping, Genghis Khan’s forces managed to free her from the Merkids. She returned heavily pregnant, forever casting a shadow over Jochi’s paternity (indeed his name means “guest” in Mongolian).

Although it was said that Genghis Khan never questioned his son's paternity, his irascible second son, Chagatai, did, sowing discord within the ruling clan. Because of this conflict between his two eldest, Genghis Khan tapped his third son, Ogedei, habitual peacemaker between his two elder brothers, to be his direct heir. From the Mongol capital in Karakorum Ogedei kept a close watch on the lands that were coming into his rule via the conquest of China. These eastern territories were the most populous and richest portion of the Genghiside domains. Further west, Chagatai would inherit the great cities of Central Asia, from Samarkand to Kashgar. The youngest son, Tolui, died campaigning in China before coming into his inheritance, the Mongol homelands, in keeping with tradition that confers upon the lastborn son their herds. To the firstborn Jochi and his heirs were then granted the vast northwestern lands, the most expansive of the domains, but also the poorest. They were also the furthest removed from Eurasian civilization’s rich hearths, which stretched in a vast arc from Anatolia to Iran, through South and Southeast Asia and up toward China. But Europe was within the ambit of the Mongol armies that coalesced into the Golden Horde, which ranged as far as the Adriatic and the forests of Poland, but that continent was only just recovering from the Roman Empire’s collapse, and its wealthiest regions were the furthest from the pasturelands that could sustain the vast Mongol herds.

Many interpreted Jochi’s dispatch to the western steppe as his father exiling him in a sense. While descendants of Genghis Khan’s three younger sons would eventually contend for the grand prize of becoming the Great Khan over all the other branches of the family, the Jochids held themselves apart, perhaps conscious of the cloud that hung over their lineage.

As implied in its title, Genomes of the Golden Horde Elites and their Implications for the Rulers of the Mongol Empire, speaks directly to the issue of Jochi’s paternity. Though it does not settle the question, it nudges the needle persuasively in one direction, finally getting us closer to what in premodern lifetimes without even our most primitive testing methods could only ever have been a matter of guesswork and speculation.

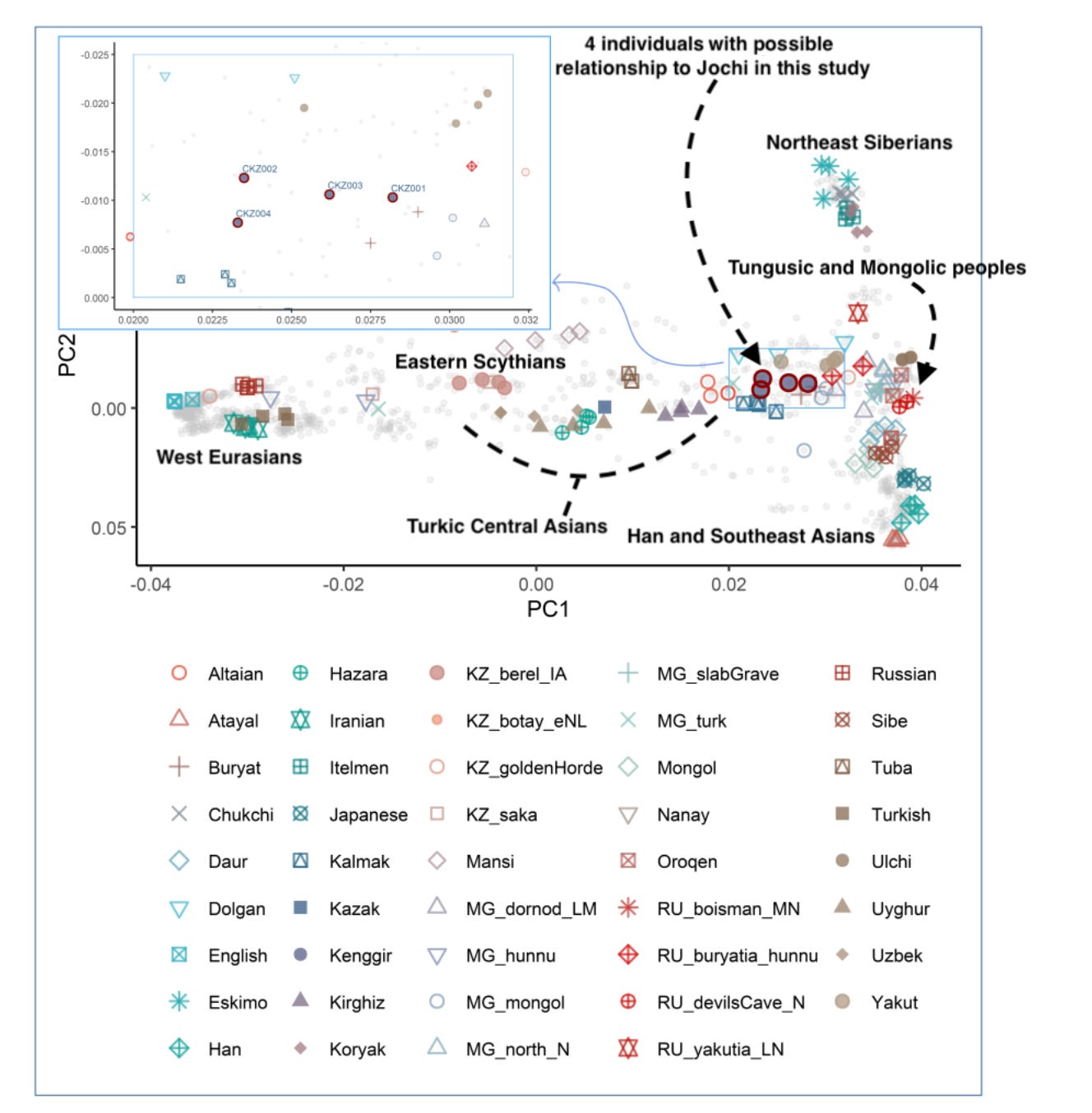

Scions of the star phylogeny

Four individuals, distributed across four mausoleums in northern Kazakhstan (the core of the Golden Horde’s territories), yielded the novel data in the preprint. Three were male, one female. One of the tombs is known locally as “Jochi’s mausoleum,” and its rich appointments and opulent grave goods suggest very high status individuals inhumed before the Mongol elites’ extensive 14th-century Islamization of the Golden Horde (as in Christianity, grave goods are not typically the norm in Islam). The three samples: CKZ001, CKZ002 and CKZ003, are male; CKZ004 is the female one. CKZ001 has been radio-carbon dated to the 18th century, while the other three individuals yielded dates 1286-1398 AD, so at least several generations after Jochi’s 1227 death. The read-depth of the genomes of the individuals from CKZ001 to CKZ004 are, in order, 14.6, 3.9, 0.80 and 3.9. These values give the expected number of times a narrow region of the genome was re-read by a sequencing machine; so by definition, the variant calls on CKZ001 are much more confident than on CKZ003. Compared to a 1,240,000- position SNP-array, a high-density array widely preferred in population genetics labs, the authors managed to pull out 1,149,000 SNPs for CKZ001, over a million for both CKZ002 and CKZ004, and even 636,000 for CKZ003. This is more than enough data for population-genomic analysis, which has a much lower confidence threshold for any given SNP than medical-grade work (where read-depth of 30 is the gold standard).