Brave new human: counting up the de novo mutations you alone carry

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #5

For 2025, I’m trying out a new occasional feature for paying subscribers, the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club: I’ll offer a brisk review and consideration of an interesting paper in human population genomics.

In the spirit of a conventional journal club, at the end of each post, interested subscribers can vote on next papers to review. I’m open both to covering the latest papers/preprints and reflecting back on seminal publications from across these first decades of the genomic era.

If your lab has work we might like or you otherwise want to suggest a paper for me to cover, feel free to respond to this email or comment on this post.

The first four editions are here:.

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Homo with a side of sapiens: the brainy silent partner we co-opted 300,000 years ago

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #5

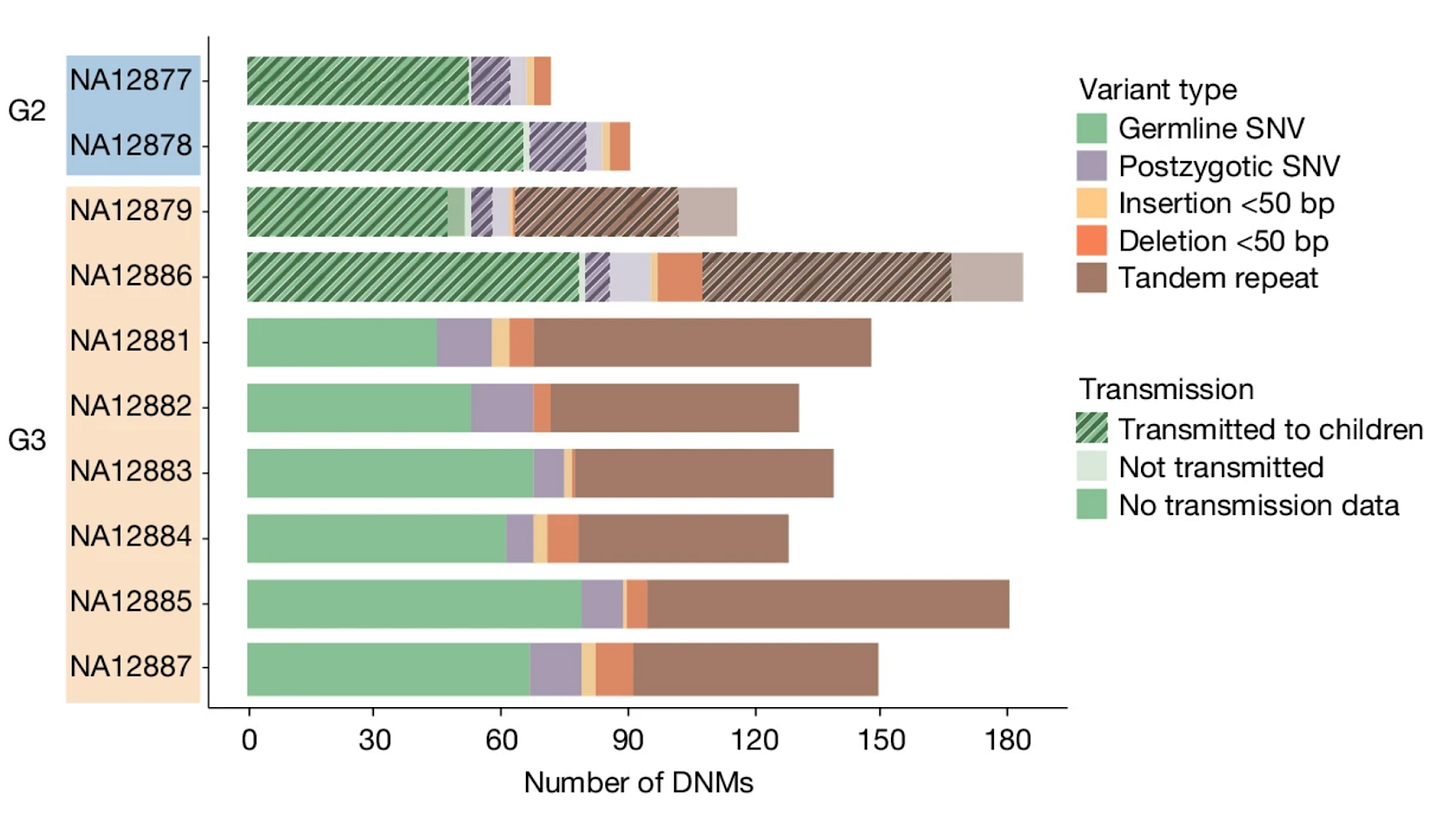

In last month’s journal club poll, the top vote getter was Humans in Africa’s wet tropical forests 150 thousand years ago (2025). But upon digging into the paper, I realized its strong archaeological focus (stratigraphy upon stratigraphy!) meant that my expertise didn’t really contribute much to unraveling it. So while I look into a conversation with someone equipped to shed more light, I instead bring you last month’s second most requested paper: Human de novo mutation rates from a four-generation pedigree reference (2025). It comes out of Evan Eichler’s group at the University of Washington, and appeared in Nature on April 23rd, 2025. The first author is David Porubsky.

Errors in us all

The paper leverages both the gift of a complete multi-generational pedigree (the culmination of an international, decades-long human genetics collaboration going back decades, that produced the first extensive maps of the human genome starting in 1987), with the now ubiquitous power of deep whole-genome sequencing, to answer what in the end is a very simple question: what is our species’ de novo mutation rate? That is, how many unique new mutations emerge every generation per individual (i.e., mutations that differentiate you from your parents). Before we dive in, let’s review where mutations come from and why they are important.

The human genome consists of three billion bases, A’s, C’s, G’s and T’s. Of these bases, a large number in any individual vary from those carried by most other humans; around 4.5 million positions (often this is approximated as every thousandth base in your genome differing from the reference genome). These divergent bases are single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs. But they are not the only genetic variants that matter, whether for functional variation or diseases. Further, in any given human, over 500,000 sections of the genome are impacted by indels, small deletions or insertions 50 bases or shorter. And finally, a class of variants qualifies as “structural,” by spanning more than 50 bases. These longer variants can still be both deletions and insertions, but at this scale they also include copy number variations, where a single gene gets copied on repeat, like a record getting stuck. Though only some tens of thousands of structural variants at most, appear in the genome, as versus millions of total SNPs, given that many structural variants number hundreds of bases in total length, you can see how their appearance has a more outsized impact on the genome than a simple headcount might suggest. Structural variants are less than 1% of the total variants in any given human’s genome, but they account for more than 50% of the DNA sequence in the genome that diverges from the reference.

Ultimately, such changes in the genome derive from mutations, and these matter for several reasons. In contexts where we call them “markers,” their utility to us is clearly as genealogical tracers allowing us to track the process of Mendelian transmission over the scale of generations and genetic evolution over millions of years. The concept of genetic markers emerged more than a century ago, when researchers began to track the inheritance of physical mutations in model organisms like Drosophila. Of course, each of the mutations in Drosophila, whether red eyes or droopy wings, was underpinned by a change in underlying genes. But in 1920, there were no sequencing machines, and geneticists did not yet even know that DNA was the specific molecular mode of information transmission genetics uses. They were simply looking at the correlation of inheritance between mutant characteristics, and from those values creating abstract genetic maps. Because recombination, the swapping of DNA segments across two copies of the genome in diploid organisms, continually breaks apart associations between genes, the more distant two underlying genes that cause the mutations, the more likely the telltale characteristics were to become decoupled as they were passed down through pedigrees.

Today population genomics takes the logic of harnessing genes as markers for other underlying phenomena to its logical conclusion. Using sequencing technology, researchers explore pedigrees and populations at hundreds of thousands of markers per individual, allowing them to infer population histories, population structure, as well as the genomic impact of evolutionary forces like natural selection. The more mutations that evade the body’s DNA-repair mechanisms, the more variation there is for these algorithms to examine. Early 21st-century molecular evolutionary studies have been blessed with an absolute surfeit of data compared to their late 20th-century predecessors because of the transformative impact of genomics. Before genome-wide technologies, most projects involving phylogenetic analyses of populations were limited to focusing on structural variants called “single tandem repeats,” or STRs. In an era where you would be lucky to get a few dozen markers, the reality that most SNPs are not all that variable (e.g., at a given position, the majority allele, A, might be at 92% frequency and the minority allele, T, at 8%), and only have four possible variable alleles, A, C, G and T, in the first place, was an additional severe limitation. In contrast, STRs record much more variation, providing more bang for the buck. An STR might consist of four bases (e.g., TTCT) repeated over and over, but the number of repeats could range between 1-30, due to structural variants’ order-of-magnitude higher mutation rate than SNPs. This means this hypothetical STR position would offer 30 potential variants, each stepwise increment in copy number marking a new variant.

Because most of the genome is not functional, like our famously vast realms of “junk DNA,” most STRs only reflect demographic forces, rather than natural selection. They are optimal DNA tracers of a population’s history, as the patterns found in these regions solely reflect drift and gene flow, or lack thereof, between populations, as well as different rates of migration and fluctuating population sizes over time.

But the STRs also appear in regions of the genome that code for protein. These are variations within genes that yield important downstream molecular consequences: the DNA is the first link in a causal chain that is translated into biochemistry (proteins and enzymes), sometimes morphology (e.g., nose shape) and even behavior (e.g., whether fish school or not). One of the best known cases of STRs causing functional change is Huntington’s disease, a fatal adult-onset neurodegenerative disease that spells loss of motor function in the space of a few years. Huntington’s is caused by a trinucleotide repeat, strings of CAG injecting themselves in the regular progression of DNA bases, their intrusion changing the value of other amino acids in the protein sequence. These repeats appear in exon 1 of the gene that codes for the huntingtin protein, which expresses in the brain. Exons are units within a gene where transcribed RNA is eventually translated into protein. This is in contrast to other parts of the gene, introns, where the transcribed RNA does not direct the making of protein. Each exon is further broken down into codons defined by sets of three bases that together each direct the synthesis of one of 61 amino acids. For biophysical reasons, the CAG repeat in the huntingtin protein gene goes rogue, proliferating at an unusually high rate, resulting in a lot of malformed protein, whose structure and folding dynamics are nonfunctional in their normal biochemical pathway. The mechanistic way the protein breaks is that the CAG codon corresponds to the amino acid glutamine. Large numbers of CAG repeats at the beginning of the gene mean that when huntingtin is translated into protein it ends up weighed down with an inordinate number of glutamine amino acids, literally slicking the normal protein with sticky “glutamine sheets” that render it non-functional.