Ghost Population in the Machine: AI finds Out-of-Africa plot twists in Papuan DNA

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #9

This year I’ve introduced an occasional feature for paying subscribers, the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club where I offer a brisk review and consideration of an interesting paper in human population genomics.

In the spirit of a conventional journal club, after each post, interested subscribers can vote on papers for future editions. I’m open both to covering the latest papers/preprints and reflecting back on seminal publications from across these first decades of the genomic era.

Previous editions:

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Homo with a side of sapiens: the brainy silent partner we co-opted 300,000 years ago

Brave new human: counting up the de novo mutations you alone carry

The wandering Fulani: children of the Green Sahara

Genghis Khan, the Golden Horde and an 842-year-old paternity test

Re-writing the human family tree one skull at a time

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #9

Today we’re reviewing a Nature paper which elucidates the deep evolutionary history of Papuans: Resolving out of Africa event for Papua New Guinean population using neural network (2025). It comes out of Mait Metspalu & Anders Eriksson’s joint groups at the University of Tartu. The first author is Mayukh Mondal, Institute of Clinical Molecular Biology, Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel, Kiel, Germany.

Papuans out of Africa

When Europeans first voyaged out into the world beyond their home continent in the 1400s and 1500s, they encountered populations of fellow humans previously unfathomed. Adrift amid unexpectedly vast new realms of human biodiversity, they groped for familiar qualifiers along which to sort their newly discovered kin. Christopher Columbus famously misidentified the natives of the New World as Indians, presuming he had reached the East Indies. A few decades later, and much further west, on the edge of Asia, Spanish Basque explorer Yñigo Ortiz de Retez, already a veteran of voyages throughout the New World and to such far flung holdings as the Philippines and the Spice Islands, named the island that spans the seas between Southeast Asia and Australia New Guinea. This was because the natives’ physical appearance, with dark pigmentation and tightly curled hair, led him to suspect a kinship with Africans of the Guinea coast, 11,000 miles away along the equator as the crow flies.

But despite its equatorial latitude, New Guinea, also known as Papua, differs significantly from Africa. Humanity’s original home continent has deserts, savannas and tropical rainforests. In contrast, while New Guinea’s coastal lowlands are all lush tropical forest, highlands dominate the spine of the isle. There, steep, ice-covered mountain peaks reach over 16,000 feet, high enough that they are capped by equatorial glaciers. These higher altitudes were ideal for horticulture, and so the island’s population’s highest concentration was found deep inland, beyond the ken of Europeans, who spent centuries pointedly skirting New Guinea’s malarial coasts along their voyages west and east. As late as the 1930s, European explorers were still discovering isolated valleys with hundreds of thousands of inhabitants, entire societies unknown to the outside world. Like Australia, New Guinea was a realm of exotic marsupial mammals; it was humans who brought the pigs, chickens and rats, and those only within the last 3,000 years.

For most of the past two million years, during the Ice Age, New Guinea and Australia both belonged to the continent of Sahul, a unified ecoregion. This long-time association explains the similarity in flora and fauna of the world’s second-largest island and its smallest continent. It also implies that the expansion of humans eastward into the western Pacific and beyond, to Australia, likely had a staging point in New Guinea, given both that locale’s proximity to Asia and its peripheral position within Oceania. But during the Holocene, about 10,000 years ago, as the world warmed and sea levels rose, Australia and New Guinea went their separate ways, as did their respective peoples and cultures. While Australia remained a continent of foragers, still living as their Paleolithic ancestors had until the arrival of Europeans en masse in the 19th century, New Guinea’s people abandoned a pure hunter-gatherer lifestyle over 7,000 years ago, turning instead to taro, yam and banana cultivation. By 2000 BC, Papuans began to re-engineer their landscape with ditches and vast clearings, evidence that by then they were expanding their system of agriculture at scale. On the edge of the Pacific, isolated from Eurasia’s social and cultural currents, New Guinea witnessed an independent farming revolution, in stark contrast to its Australian neighbors to the south.

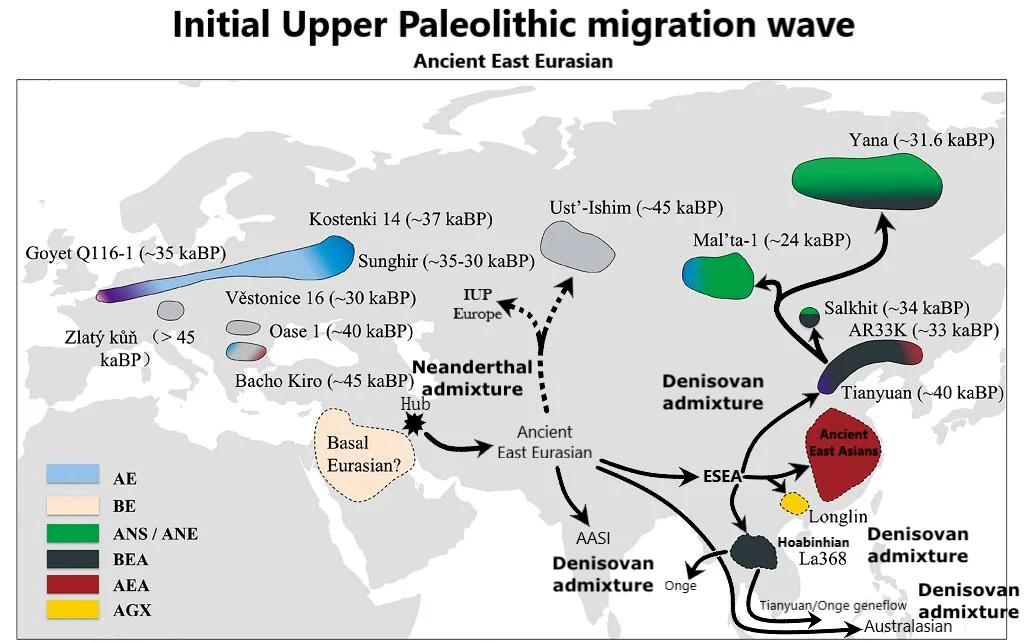

Papuans, in their splendid isolation, might seem to be of little interest to the broader narrative of human evolution and genetic history, but it is their very distance from the migrations and the rise and fall of empires that renders them notable. Until recently, New Guinea seems to only have ever been occupied by the first modern humans to settle the island, with nothing beyond minor changes upon Austronesians’ arrival to its shores 3,000 years ago. But in 2010 New Guinea and Papuans were suddenly thrust to the center of human evolutionary discoveries. In that year, researchers discovered upon sequencing that the genome from Denisova cave in Siberia matched about 5% of the New Guinean people’s ancestry (and almost none outside of Australasia). Then, in 2016, other researchers examining Papuan whole genomes concluded that the people might also harbor ancestry from an earlier out-of-Africa migration than the well-characterized expansion 50,000 years ago that swept from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

So in the last 15 years New Guinea has gone from an interesting and curious Pacific outpost of the human species to being at the center of several deep and essential questions. How many distinct out-of-Africa migrations have humans actually undertaken? And how many admixture events with earlier human species? 2025’s Resolving out of Africa event for Papua New Guinean population using neural network leverages the data from ancient DNA, including 320 whole genomes, and the computational power of the 21st century in the form of neural networks, to extract greater analytic insight and finally tackle these evolutionary genetic questions.

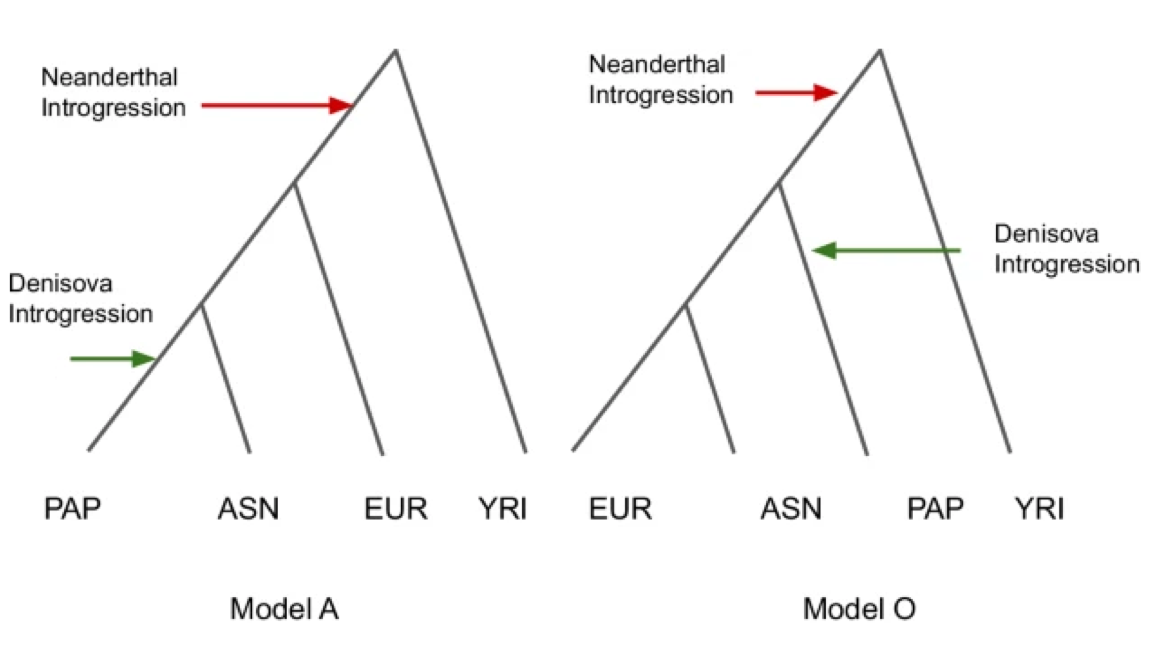

Doing deep learning on the Papuan genome

When Nature published 2010’s Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from Denisova Cave in Siberia, paleogenomics was in its infancy, the total number of human whole-genome sequences was relatively small and analytic methods were still being developed to grapple with the welter of data. A total of 12 modern whole genomes were analyzed in that paper at 1 to 5-fold coverage, the number of times a region of the genome is resampled by the sequencing machine (for medical-grade diagnostic sequencing, we now usually require 20-30 fold coverage to ensure each genetic call’s accuracy). 2016’s Genomic analyses inform on migration events during the peopling of Eurasia, was a step forward, with “483 high-coverage human genomes from 148 populations worldwide.” That being said, population genomics was then arguably still establishing its footing, with analyses only recently having gone from inspecting a single precious whole genome to grappling with hundreds. This step change had just come within the space of five years. The most surprising result from the 2016 paper was that at least 2% of the Papuan genome originates from an early expansion, a largely false dawn of modern humans who left Africa long before that fateful little exodus 50,000 years ago. But it was greeted with some skepticism at the time given prior issues in the field with artifactual errors being introduced when the nuances of whole-genome analyses were still not wholly appreciated (a 2011 paper on Australian Aboriginals with a similar result seems to have suffered from this issue).