Antiquity’s miracle skin whitening method: migrate to Sweden, wait millennia

Journal Club #11: the DNA of ancient pigmentation and the drive to pallor

Welcome back to the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club, an occasional feature for paying subscribers where I review interesting papers in human population genomics. In the spirit of a conventional journal club, after each post, interested subscribers can vote on papers for future editions.

Recent editions:

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Homo with a side of sapiens: the brainy silent partner we co-opted 300,000 years ago

Brave new human: counting up the de novo mutations you alone carry

Genghis Khan, the Golden Horde and an 842-year-old paternity test

Ghost Population in the Machine: AI finds Out-of-Africa plot twists in Papuan DNA

Immigrants of Imperial Rome: Pompeii’s genetic census of the doomed

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #11

Today we’re reviewing a PNAS paper, Inference of human pigmentation from ancient DNA by genotype likelihoods (2025). The authors use paleogenetics and the latest in genomic inference to shine new light on the evolution of pigmentation in Eurasia, and particularly in Europe. It comes out of Guido Barbujani’s lab in the Department of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Universitá degli studi di Ferrara, Ferrara. The first author is Silivia Perretti, at the same university.

By your skin you shall be known

“Of the Ethiopians above Egypt [Nubia] and of the Arabians the commander, I say, was Arsames; but the Ethiopians from the direction of the sunrising (for the Ethiopians were in two bodies [Nubians and Indian]) had been appointed to serve with the Indians, being in no way different from the other Ethiopians [Nubians and Indians serving together], but in their language and in the nature of their hair only; for the Ethiopians from the East are straight-haired [India], but those of Libya have hair more thick and woolly than that of any other men [Nubians].”

— Herodotus, The Histories (Book 7, Chapter 70), circa 440 BC

Skin is our largest organ. It’s one of our most faithful indices of age and health. A potential mate’s complexion is critical information in an evolutionary context, signalling both fitness in spite of environmental stress, and underlying genetics. But not everything is about age and health. Perhaps one of the most important aspects of skin, its color or shade (something to which humans have paid immense attention for all of recorded history) is to discern race and identity. The ancient Egyptians perceived the people of the Levant to have been “yellow,” while already calling the Nubians to their south “black.”

Herodotus, arguably both the first historian and anthropologist, illustrates the centrality of coloration in identifying and classifying human populations. In The Histories, he mentions both the people of the Indian subcontinent and those of Sub-Saharan Africa as “Ethiopians,” from the Greek word aithíops, meaning literally “burnt face” or, in practical terms, red-brown. Part of this conflation of Africans and Indians is some early Greeks’ confusion over whether India and Africa were somehow geographically connected via a land bridge far to the south. But clearly a major reason that Herodotus made the connection is that these were the two darkest populations the Greeks knew in that time period.

This fixation on skin color almost alone to make identifications seems universal, whether the population are of a darker range of complexion or one on the paler side; Frank Dikötter, in The Discourse of Race in Modern China, notes that before the 20th century, the Han Chinese referred to themselves as “white,” in contrast to “black” peoples, like those of Cambodia. Upon encountering Europeans, they observed that this new people was somehow like them in color, white, while also unlike them in a host of other characteristics (e.g., eye color and shape, full beards and nose shapes). Only in the 20th century, with new ideas of scientific racialism, did the Chinese shift to thinking of themselves as “yellow,” in contrast to white Europeans.

The origin of the variation in human complexion remains of deep scientific interest. In The Third Chimpanzee Jared Diamond argued that variation in pigmentation across human races was driven by sexual selection, extending on Charles Darwin’s assessment in The Descent of Man. Darwin rejected the idea that adaptation through natural selection caused the differences across the spectrum of skin colors. He noted that the people of the Amazon were far lighter than those of Africa, while indigenous Tasmanians, despite living at the same latitude south of the equator as Spain is north of it, had black skin.

Darwin believed that skin color was primarily an aesthetically driven trait, with people of different regions preferring different complexions in their mates. Nevertheless, the majority view today is roughly in line with the ancient Greeks’: excessive radiation at lower latitudes drove selection for darker skin, while reduced sun exposure at higher latitudes drove lighter skin’s development in order to better synthesize vitamin D (Peter Frost’s Fair Women, Dark Men: The Forgotten Roots of Color Prejudice is probably the most extensive contemporary articulation of the alternative sexual selection theory).

Though skin color has interested biologists and anthropologists for over a century, only after the year 2000 has genetics truly begun to understand its heritable basis with granularity. In his 2005 book Mutants, Armand Leroi could still write an epilogue lamenting that we didn’t yet know the biological basis of variation in traits like skin color. But within a year, Trends in Genetics had published a review paper “A golden age of human pigmentation genetics,” reporting on numerous new and exciting findings associating particular genes, like SLC24A5 and OCA2, with lighter skin and blue eyes, respectively. Within a few years this led to the emergence of algorithms like HirisPlex, which looks at 41 markers to predict eye, hair and skin color. Forensic genomics of this sort is all fun and games when you see your phenotype correctly predicted on 23andMe, but advances in the field are in fact largely driven by crime scene investigation, where the authorities need to reconstruct the physical appearance of perpetrators from DNA left behind.

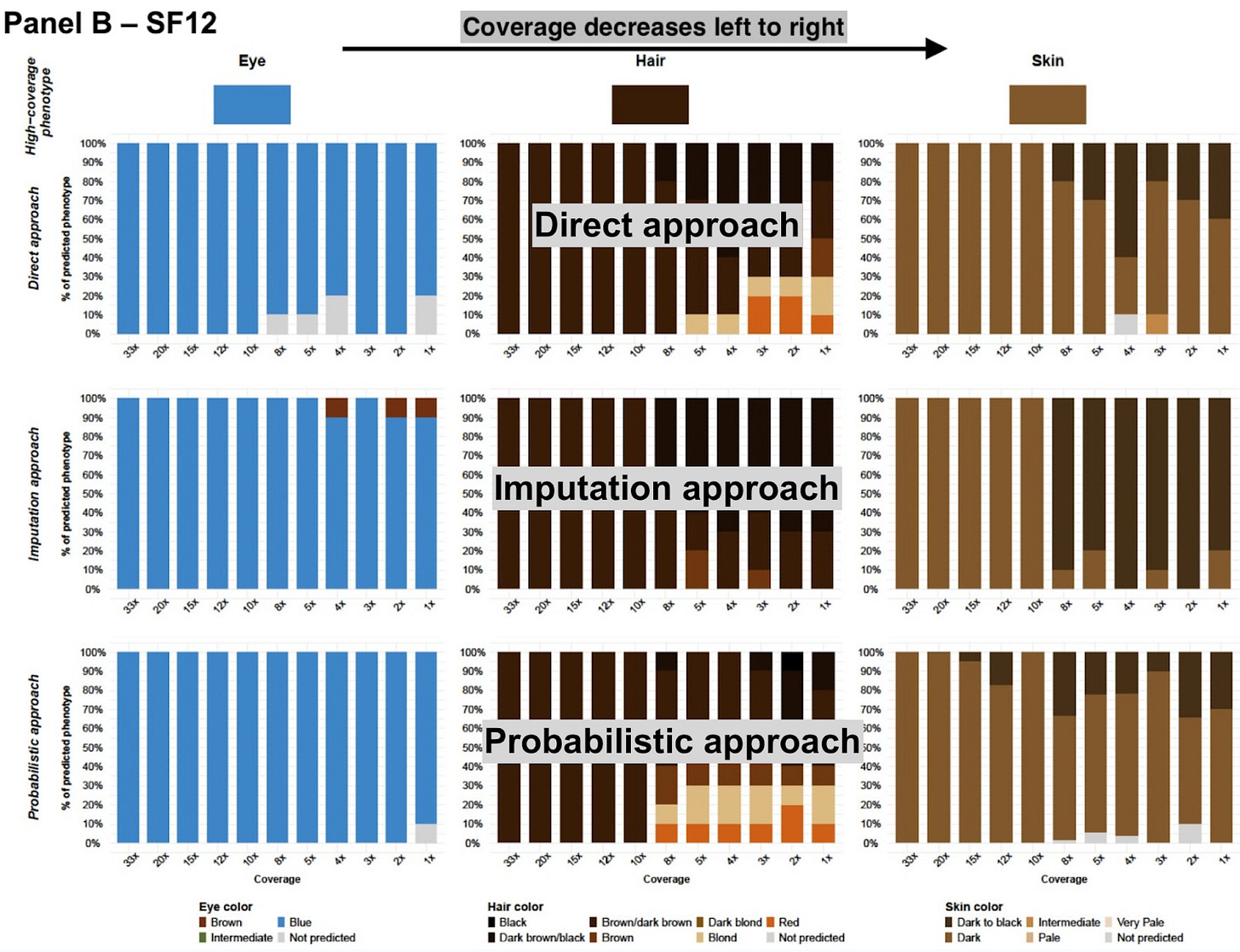

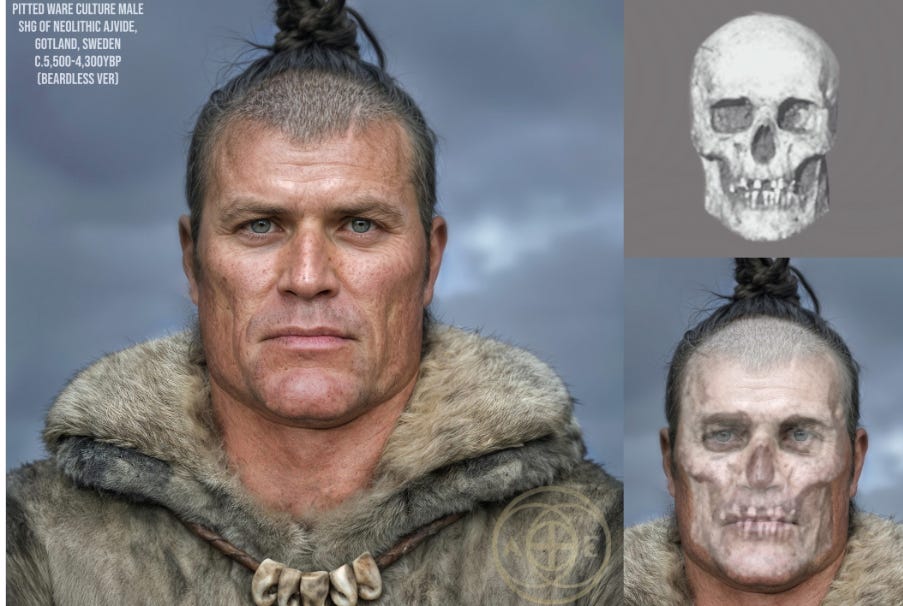

Of course, phenotypic predictions can offer a utility beyond closing cold cases. Paleogeneticists too need to reconstruct the faces of the past, as we attempt to understand how and why our appearance changed as we expanded out of Africa to Europe, Asia and Oceania. But ancient DNA is often hobbled by quality far lower than that of crime scene samples; cold cases might be, at most, decades old, whereas ancient DNA can have had some 10,000 years to degrade. Better techniques of extraction innovated by biologists at the bench have resolved some of this, but statistical genomics has also played a role. Instead of limiting themselves to “calling” only genotypes that can be deduced from high confidence positions, researchers today also have available probabilistic Bayesian methods developed for low-coverage genomic sequencing; in short, they can also infer phenotype from a large number of lower confidence marker positions. Old data, it turns out, can be taught new tricks.

Beyond black and white

Human genomics emerged as a field after 2000, upon the release of the draft human genome. But it remained squarely “blue sky” science in the early aughts. Whole-genome sequencing was a theoretical possibility, but still largely beyond the reach of even well-funded research labs until the year 2010. Then sequencing costs finally dipped below $10,000 per sample, and it became conceivable that insurance might reimburse the costs of tests done for medical diagnostic purposes. The move from super-expensive proof-of-concept science to mass-market technology drove the development of a convention to ensure quality control.

This was essential given that the emerging sequencing technologies as the 21st century dawned still had significant baked-in error rates. In 2010, the HiSeq 2000, Illumina’s workhorse machine, had an error rate of about 1 in every 200 calls, or 0.5%, meaning that every single assignment of A, C, G or T to a particular base in the three billion positions of the human genome, would be wrong 0.5% of the time. If you take a test in school, 99.5% is excellent; you know the material. But the “material” in a whole genome sequence is...vast; “knowing” 99.5% of three billion bases means you’re reporting some 15 million positions wrong. We already knew that the average human being differs from the reference genome at some 5 million positions. Meaning that if you accept that error rate as unavoidable, most of the “variation” you supposedly detect is just going to be you getting a wrong read (you’ll mistakenly differ from the reference genome three times for every meaningful difference detected). In medical testing, a 1 in 200 error rate is too high, especially for rare conditions; too many “positive” results will actually just be errors. Even for a single patient, a medically actionable test with a 0.5% error rate is unacceptable. Scientists’ and clinicians’ 2010 solution (and the standard ever since)? Repetition. Just sequence the same sample, over and over.

In genomics, the term “coverage depth,” roughly refers to the number of times a base is called by a sequencing machine (if you want to get into the precise details, it actually refers to the number of short sequence reads piled up in each region of the genome). The “gold standard” for coverage depth was 30x, so the machine would read every base roughly 30 times. If the error-calling rate is independent, an outlier call at a given base will be easily identified as aberrant. In a pile of 30 reads, there is a 15% probability of outlier miscalls. But those are easily identified. On the other hand, if you have a genuine polymorphism, where the particular sequence differs from the reference, then the vast majority of the 30 calls will differ from the reference, allowing you to confidently conclude that you have found a true variant.

For a medical doctor, getting 30x coverage has just become standard practice; yes, it costs more for the sequencing machine to return so many reads, but the alternative of high misdiagnosis rates necessitates it, so insurance will reimburse. Forensics and ancient DNA face a different set of problems: the genetic material is often severely degraded, contaminated or in very limited supply. Many ancient DNA studies only have data with very low coverage, often lower than 1 (meaning many bases don’t get called at all, and you are just subsampling the genome). This can actually be adequate data for many population-genomic purposes. A typical human genome has about 4.5 million polymorphisms, but you can perform a reasonable principal component analysis (PCA) with some 1,000 of them. Where low coverage breaks down is in prediction of individual phenotypes. HirisPlex has 41 markers; and you really require all of them to make good predictions. Ideally, you would have high-quality data and could make confident predictions with a very large number of high quality genotypes. But ancient DNA rarely approximates an ideal world.