Immigrants of Imperial Rome: Pompeii’s genetic census of the doomed

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #10

Welcome back to the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club, an occasional feature for paying subscribers where I review interesting papers in human population genomics. In the spirit of a conventional journal club, after each post, interested subscribers can vote on papers for future editions.

Here are the most recent past editions:

Genghis Khan, the Golden Horde and an 842-year-old paternity test

Re-writing the human family tree one skull at a time

Ghost Population in the Machine: AI finds Out-of-Africa plot twists in Papuan DNA

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #10

Today we’re reviewing a Cell paper, Ancient DNA challenges prevailing interpretations of the Pompeii plaster casts (2024). The authors use paleogenetics to shine new light on the backgrounds of the famous victims of one of history’s best-known natural disasters. It comes out of Alissa Mitnick’s group at Max Planck Institute. The first author is Elena Pilli of the Università di Firenze.

The End of the World As They Knew It

“Its general appearance can best be expressed as being like an umbrella pine, for it rose to a great height on a sort of trunk and then split off into branches, I imagine because it was thrust upwards by the first blast and then left unsupported as the pressure subsided, or else it was borne down by its own weight so that it spread out and gradually dispersed. In places it looked white, elsewhere blotched and dirty, according to the amount of soil and ashes it carried with it.”

- Pliny the Younger, 79 AD, later recalling his distant view of Mt. Vesuvius’ volcanic plumes

In 79 AD, Imperial Rome’s first flowering had passed. Over a decade prior, Nero, the last of the Julio-Claudians, had committed suicide. The end of Rome’s first imperial dynasty left a leadership vacuum that sparked civil war, eventually bringing Vespasian to the throne. A humble Italian from a town northeast of Rome, Vespasian had no roots in the great city itself. Ironically, it was he who established the practice of the Roman sovereign bearing the title imperator; unlike his Julio-Claudian predecessors, his lineage was obscure, so his right to rule rested purely on military achievement and the power conferred upon him by his armies. Vespasian brought the empire back together under firm and pragmatic rule after the degeneracy of Nero’s reign and the disorder of civil war. After a decade on the throne, in the spring of 79, Vespasian died, to be succeeded by his son Titus. Roman historians would judge Titus’ short two-year reign kindly, but one of the first things he had to attend to was the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in southern Italy, the second major event that year to shake the empire after Vespasian’s death.

At 4,200 feet (1280 meters), Vesuvius today is regarded as a menacing presence looming silently over the bay south of Naples; it is a well-known active volcano. But 1,946 years ago, it had lain dormant for so long that in 23 AD when Strabo wrote about the region, he depicted the mountainside as covered in vineyards and farms, with small villages nestled around its base. In the 60s, the region had witnessed multiple large earthquakes, so when in the days leading up to that cataclysmic day in 79, multiple tremors shook the area, citizens apparently saw them as business as usual. Ancient Pompeii, on its southern slopes, and seaside redoubt Herculaneum, just to its west, were the larger towns in the region, wealthy, well-run Roman cities with a high quality of life in a time of relative peace for the empire. When their neighboring mountain began erupting, the citizens were caught unprepared. The next two days would subject the region to cataclysm on a scale few of us are equipped to fathom. More earthquakes punctuated days of inferno as a 21-mile high cloud continued hailing rock and ash on the cities around the clock; the power of the explosion itself is estimated to have released 100,000 times the thermal energy of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

There are no known eyewitness accounts from survivors who escaped either town. Only the Roman jurist Pliny the Younger, an eyewitness of the eruption from safety kilometers away across the bay, recalled the day in letters to Tacitus written decades later. He recalled those rumblings in the days before the cataclysm, but noted that the region had been so seismically active the locals took no particular notice. Pliny observed the mass destruction and chaos from far off on the other side of the bay. His uncle, Pliny the Elder (the famous encyclopedist and friend to Vespasian), sailed across the bay into the upheaval, and died attempting to aid those fleeing. Pliny the Younger describes seeing a giant plume of ash and pumice erupting above the distant mountain at 1 p.m. At that time, over 11,000 people lived in Pompeii and some 5,000 in Herculaneum. Most seem to have survived, scattering across the region. But ash and pumice buried both their vibrant cities overnight, sealing them up, in many ways fossilized as they had been on one arbitrary 79 AD afternoon (whose precise season is still debated, but was probably either late summer or early autumn), until antiquarians began excavating them in the 18th century.

Pyroclastic material, ash, pumice, and rock fragments, blanketed both Pompeii and Herculaneum. Pompeii, downwind of Vesuvius, apparently endured an uninterrupted rain of pumice (a steady downpour of small stones falling from the sky) from the eruption’s ash plume for 18 hours after the plume first formed. The air temperature increased to lethal levels over the day, and ash and stone continued to rain down on the city, all eventually entombing the sites. Herculaneum, in contrast, was upwind of Vesuvius and so escaped the initial pumice rain from the eruption plume. Closer to the base of the volcano though, overnight it was abruptly engulfed by a pyroclastic avalanche of mud, ash and superheated fumes moving at 100 mph; a flow of volcanic material super-heated to temperatures up to 500 degrees Celsius that carbonized wood furniture, doors, beds, bread and even an entire private library of papyrus scrolls, burying the town to a depth of 25 meters.

In Pompeii meanwhile, during the later phases of the eruption, the morning after the plume was first sighted, anyone who had remained in the city after the long downpour of pumice rain was doomed to be caught in the same sort of delayed pyroclastic surge as had suddenly engulfed Herculaneum overnight. But by the time the later round hit Pompeii, the temperatures seem to have dropped to something closer to 300 degrees, which would prove a decisive adjustment from the levels during the cataclysmic avalanche that had doomed Herculaneum. Pompeii’s round of pyroclastic surges overwhelmed victims who were by then sheltering indoors from the pumice rain pelting their city, clearly catching them unawares, many cowering or huddling together inside.

Those relatively lower temperatures that killed Pompeii’s victims have made all the difference to science though; they mean that despite being abruptly engulfed and killed by the surge, this time the victims’ bodies did not immediately disintegrate, as they had in Herculaneum; instead the hail of ash and stone continued to steadily accumulate around them over the hours. In time, their bodies would decay, but by then the detritus of the eruption around them had long since fully cooled and hardened, leaving the solidified concrete-like mass studded with human-shaped cavities in the precise shapes in which they had been suddenly stilled. In 1863, Italian archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli realized that pouring plaster into these hollow voids would recapture the precise form of the humans who had died that day, yielding lifelike sculptures eternally suspended in the private moments and interactions at the instant tragedy engulfed them.

More than form alone

The 104 men, women and children who both perished in Vesuvius’ infernal aftermath, and whose final moments were then captured for us as if someone had pressed pause on a video, have gone on to fuel a century of archaeology. The possible life narratives their final moments suggest to the fertile human imagination have grown rich enough, whether those be a mother and child clinging together or a slave girl perhaps callously left behind to fend for herself, to serve as the basis for numerous documentaries in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The vivid details amid calamity from what began as an ordinary day in two comfortable small cities have always offered an irresistibly human-scale counterpoint to the cold perfection of marble busts and the mute austerity of long since stripped amphitheaters that so often epitomize Roman antiquity’s material record.

The everyday objects preserved in the homes, the profane graffiti in public spaces, the rarity of ancient human bodies not laid lifelessly to rest, but frozen in the midst of living bring vividly to life the material reality of the vast majority of Roman citizens. For once we glimpse not the society’s storied generals and orators, but its humble farmers, merchants, potters, bakers and mothers. Certain of the most vividly captured among Pompeii’s doomed were in this way granted a belated afterlife far more evocative and enduring than the over 10,000 survivors who moved quickly enough to stream out of the doomed cities and reach safety at points north and south. The eloquence of those often anguished, unaffected final human gestures naturally move us to sympathize with them far more powerfully than we relate to those who fled. In lives abruptly cut short, they eventually had far more enduring legacies than actual eye-witness survivors lucky enough to live out the rest of their lives as refugees in other cities. The host of documentaries their remains inspired hinged on narratives spun out of the apparent pathos of their poignant final moments.

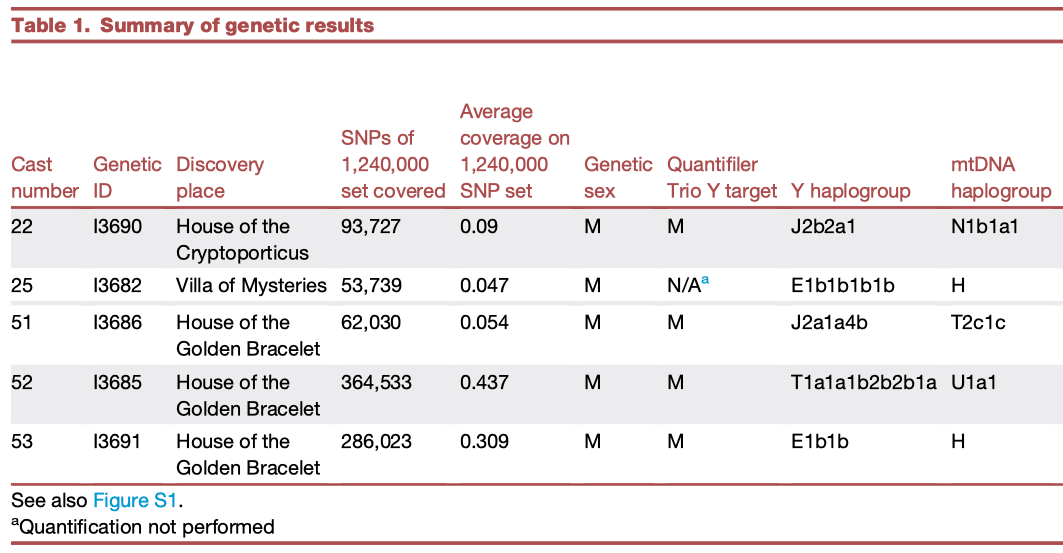

Today, though, we have at hand a powerful new way to understand those people of the past, no matter where we find them or how their final gestures strike us: their genetic interrelationships. Ancient DNA challenges prevailing interpretations of the Pompeii plaster casts, published in Cell, is the first comprehensive paleogenetic survey of multiple sets of remains (one single sample had been studied previously). When Italian archaeologists created the plaster casts, in some cases they unknowingly preserved remnants of bones within them. The research team for this study painstakingly probed the casts for traces of DNA adequate to sequence and were able to retrieve varying amounts from seven total casts, five of them in appreciable quantities. These casts had been the subject of scholarly analysis for decades, but now we could precisely delve into their genetic backgrounds and relationships.

One of the simplest things to test immediately upends some of our emotional interpretations of the figures and their poses: all five individuals are indisputably male, as attested by their Y chromosomes. This basic fact triggers revisions to some of the narratives their poses had always suggested. 1974 saw completion of the so-called House of the Golden Bracelet’s excavation. The private residence was a sumptuously decorated multi-level elite Pompeii home; its rooms yielded casts of four individual humans. The site was named for cast 52, who died wearing a massive 1.34-pound solid gold two-headed snake bracelet featuring a disk with the lunar goddess Selene, which was both evident in the relief of the cast and actually survived intact inside the cavity where its bearer’s remains decayed. An incomplete cast of a small child, cast 51, was positioned on the apparently recumbent figure’s lap. Given the opulent home, the extraordinary bracelet and the pose with figure 51 against her, archaeologists had posited that this was a wealthy mother sheltering in her home, protecting her child. Archaeologists surmised that another adult nearby, cast 50, was the father. The home’s fourth and final cast, number 53, expired alone in a different room, and was assumed to perhaps have become separated from the parents in chaotic final moments. The figure’s diminutive dimensions and a bulge at the crotch in the plaster, presumed to be a penis, suggested this child who died alone was a boy of about four. Archaeologists had imagined this whole grouping to be a nuclear family.

But genetic tests immediately found that individual 52, the maternal figure with the dramatic bracelet, had a Y chromosome and so was actually male. The figure we read as maternally protecting a child, was in fact a man. Next, comparison of individual 51, 52 and 53’s genomes show they are also clearly not biologically related (and even if individual 52 was instead the two children’s father, they would share his Y chromosome, which is also not the case). Though nuclear DNA was not retrievable for the individual in cast 50 (meaning we also cannot confirm sex), presumed to have been the father in the old model, mtDNA proved callable. Perhaps individual 50 was the mother of one of the children? Again this individual showed no genetic relationship to the others in the house (a cut and dried judgement, since humans inherit mtDNA from their mothers). So, genome-wide and mtDNA analysis now refutes five decades of conjecture that this was a conventional family unit, at least on any biological basis.

The number of Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) retrieved from each of the five is more than sufficient to assign biogeographic ancestry, for which we usually set a floor of 10,000 markers (even if a minimum of closer to 100,000 markers is preferable for more sophisticated methods). A PCA plot projecting the Pompeii individuals shows they were all of Mediterranean provenance, but not clustered together biogeographically. All the evidence then points to the three fully genotyped individuals in the House of the Golden Bracelet being entirely unrelated individuals (with the fourth being at least maternally unrelated), and what’s more, with a very diverse range of origins.