Re-writing the human family tree one skull at a time

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #8

This year I’ve introduced an occasional feature for paying subscribers, the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club where I offer a brisk review and consideration of an interesting paper in human population genomics.

In the spirit of a conventional journal club, after each post, interested subscribers can vote on papers for future editions. I’m open both to covering the latest papers/preprints and reflecting back on seminal publications from across these first decades of the genomic era.

If your lab has work we might like or you otherwise want to suggest a paper for me to cover, feel free to respond to this email or comment on this post.

Previous editions:

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Homo with a side of sapiens: the brainy silent partner we co-opted 300,000 years ago

Brave new human: counting up the de novo mutations you alone carry

The wandering Fulani: children of the Green Sahara

Genghis Khan, the Golden Horde and an 842-year-old paternity test

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #8

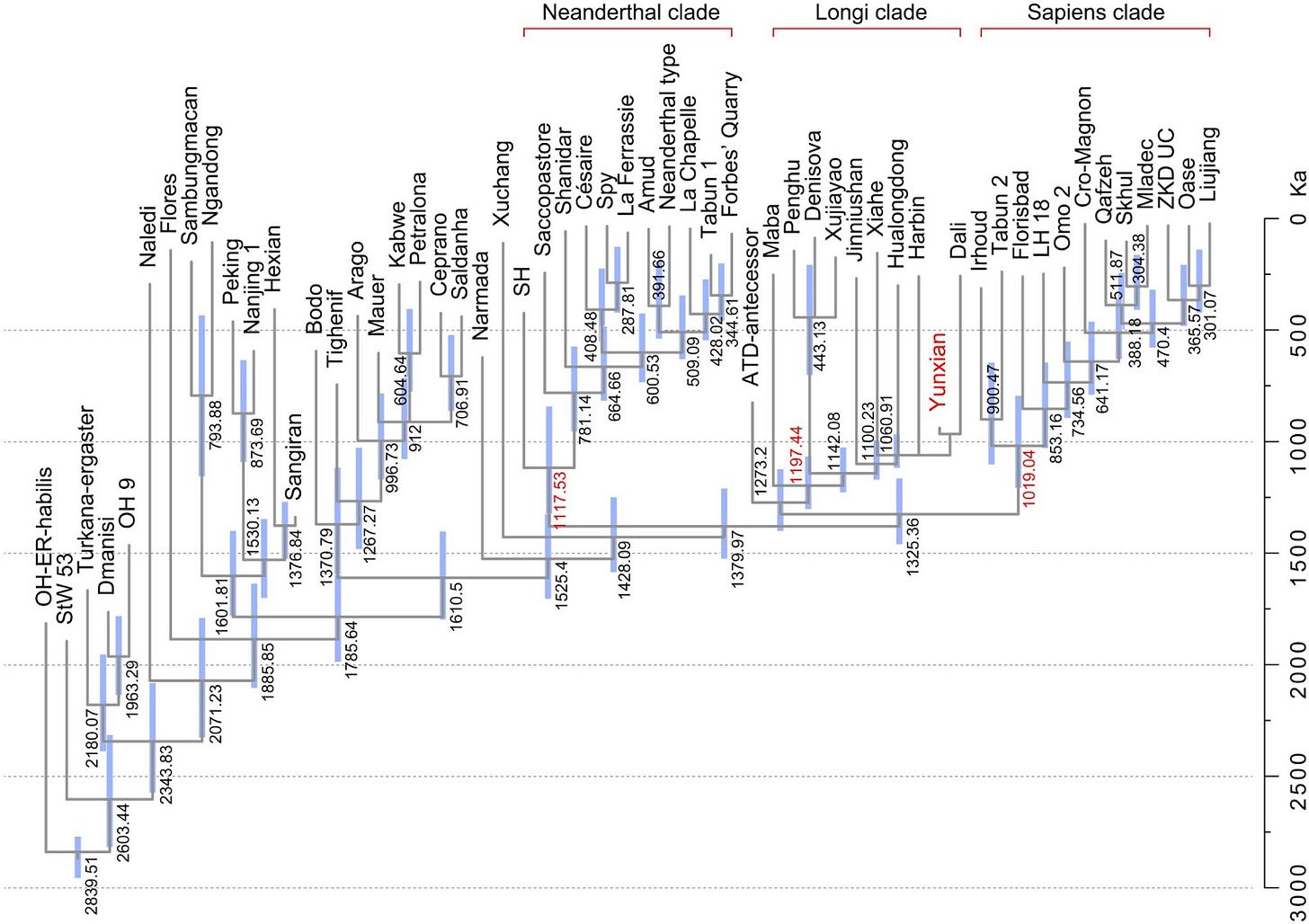

Today we’re reviewing a paper in Science which challenges established narratives of human evolutionary relationships: The phylogenetic position of the Yunxian cranium elucidates the origin of Homo longi and the Denisovans (2025). It comes out of Xijun Ni’s group at the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. The other senior researcher is Chris Stringer at the Centre for Human Evolution Research, Natural History Museum, London, The first author is Xiaobo Feng, School of History and Culture, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China.

A constellation of fossils

Lucy, Turkana Boy, Java Man and Ardi. These are just a few of the seminal fossils widely known by name for their role in shaping and re-shaping our understanding of human evolution over the last century. They have been instrumental in how scholars construct the human family tree, predating DNA evidence by decades. Fossils, the mineralized remains of bones and teeth, offer a concrete solidity DNA data cannot. Simply beholding a single Neanderthal skull brings home how profoundly different they were from us given their robustness and unique morphology. It was fossil evidence from Africa, in the first half of the 20th century, that finally convinced physical anthropologists Homo’s origin was on that continent, rather than Eurasia (on this, Charles Darwin was correct, though his argument had been based more on biogeography, as our nearest relatives live in Africa).

The individual fossils above exemplify new lineages, and sometimes even represent new species. Lucy (circa 3.4 million years BP) was the type specimen for Australopithecus afarensis, while Turkana Boy (circa 1.5 million years BP) is the most complete Homo erectus to date. The 2009 publication of Ardipithecus ramidus, dated to 4.4 million years ago, was the lynchpin in establishing the “missing” link between Miocene apes and later hominins, with the new species exhibiting both arboreal and terrestrial adaptations, and thus defining a critical waypoint in the transition to full bipedalism.

It is notable how much of our understanding of human evolution has been gleaned from truly fragmentary evidence. The stories we tell ourselves of millions of years of human evolutionary history rest on a few thousand fossil elements. Paleoanthropologist John Hawks has quipped that a large room might be sufficient to house all the world’s pre-modern hominin remains. Turkana Boy, an 80% complete set of fossilized human remains, is the exception. The vast majority of fossil specimens are much more fragmentary; sometimes as little as a jawbone or a femur.

The very informative power of a single fossil, and the scarcity of remains, has often generated human drama in the field. Berkeley anthropologist Tim D. White took 16 years to finally publish his team’s analyses of Ardi after its 1994 discovery. Toumaï, the name for the human-chimp-gorilla common ancestor discovered in Chad in 2002, has already engendered a couple decades of controversy with disputes over who should be allowed to analyze the remains. The scarcity of high-quality fossils owes both to the small number of hominins alive at any given time before agriculture, and to the fragility of our skeletons. But this scarcity means that human fossils are a precious commodity whose control and distribution can make or break careers; the re-possession of the original “Hobbit” remains in Flores by Indonesian researchers from its Australian discoverers was initially nearly as big a story as the diminutive humans themselves.

But today fossil-informed paleoanthropology is itself evolving into a different type of science, less fixated on individual remains, and more focused on a synoptic understanding of a specimen in the context of the broader array of samples. Lee Berger and John Hawks, lead scientists at the fertile Homo naledi site, the Rising Star Cave system in South Africa, have both pushed for the fossils recovered to be released rapidly into the public domain, rather than held closely for decades by a few research groups. The team Berger led has the luxury to be generous because the Homo naledi remains in South Africa are so numerous, with at least 15 skeletons and more than 1,000 smaller specimens, from skulls, teeth, ribs, hand and feet bones down to inner ear bones. The influx of fossil data driven by an “open science” paradigm coupled with emerging new computer-assisted analytic techniques, together allow researchers to extract much more information from any single fossil.

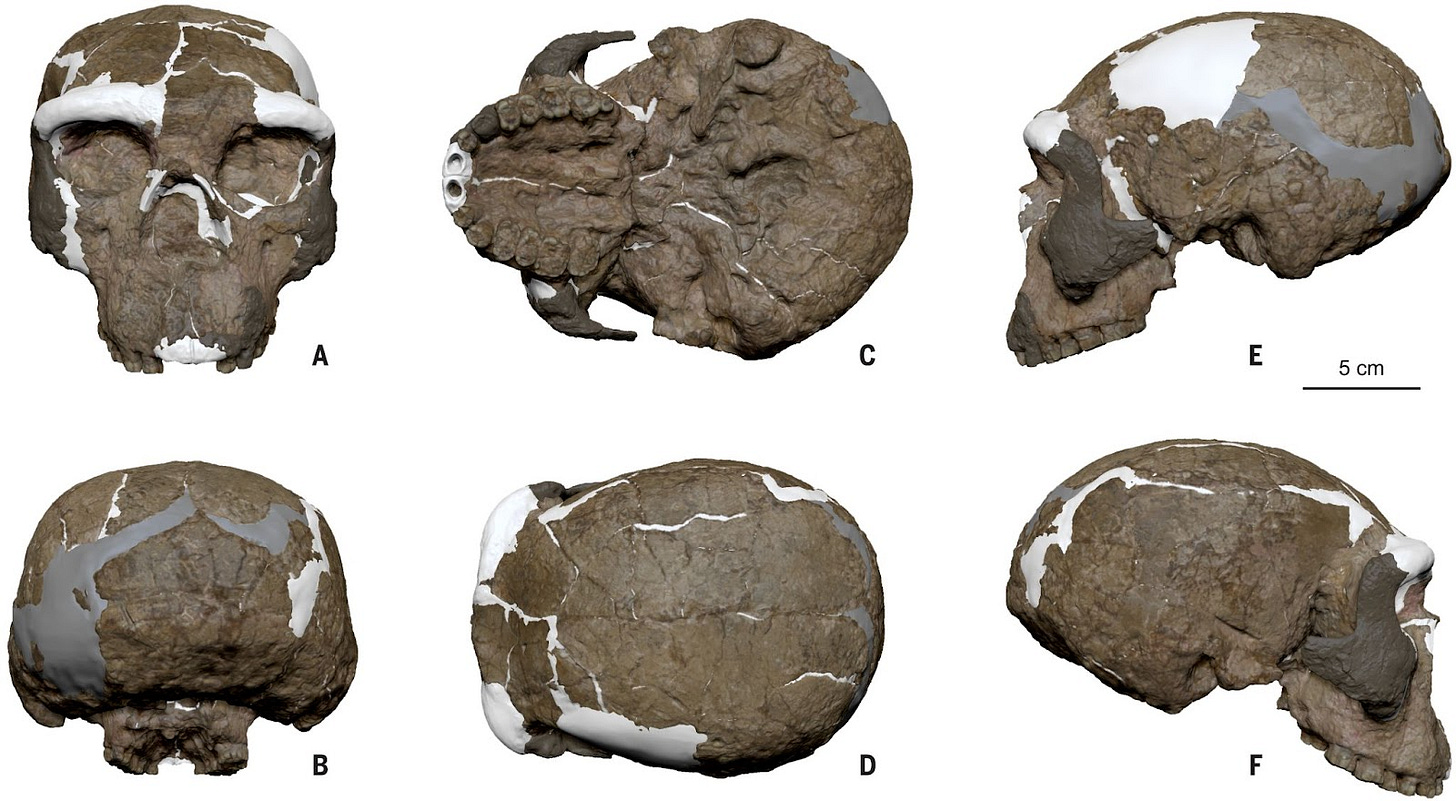

The phylogenetic position of the Yunxian cranium elucidates the origin of Homo longi and the Denisovans illustrates the fruitful synthesis of methods old and new. In the past, the cranium of the Yunxian 2 specimen would have been unusable for analysis, but researchers turned to computational methods to project it back to its original state. This enabled analysis in the context of the much larger number of fossils already extant in the literature. Yunxian 2 has a very early and precise date and its completeness makes it an excellent addition to the fossil record. Its insertion into our current data forces a reinterpretation of the human phylogenetic tree both in overall structure and branch length. However, as is so often the case in this field, Yunxian 2 likely prefigures pending analysis of another specimen from the site, Yunxian 3, which researchers have yet to discuss, in keeping with the older practice of researchers hoarding findings until publication, even though insiders presumably know the general conclusions. These territorial practices artificially delay dissemination of scientific knowledge, and are what Berger and Hawks have been fighting against.