Time Well Spent - 1/1/2024

New Years Edition

For the first time ever, parents going through IVF can use whole genome sequencing to screen their embryos for hundreds of conditions. Harness the power of genetics to keep your family safe, with Orchid. Check them out at orchidhealth.com.

Note: I discount annual subscriptions to this Substack twice a year, Cyber Monday and New Year's Eve. As this email goes out, the 24-hour New Year's discount has 9 hours left. Details on the sale here. Thank you and happy 2024 to all my subscribers!

Your time is finite. Your phone and the internet stand ready to help you squander it. Here are my latest picks for spending it well instead. Feel free to add more in the comments.

Books, what else?

Psychology is a peculiar science. It is both incredibly popular and an eternal punchline. Headline from The Onion in 2020: “Majority Of Psychological Experiments Conducted In 1970s Just Crimes.” Another from 2014, again in The Onion: “Psychology Comes To Halt As Weary Researchers Say The Mind Cannot Possibly Study Itself.” Despite the discipline's challenges that inspire such mockery, the human mind craves to understand itself, whether on rarified topics like its origins through evolutionary psychology or “news you can use” like individual mental well-being fostered by clinical psychology. The impulse to study the mind is ancient. More than 2,000 years ago, the Upanishads recorded early Indian philosophical explorations of consciousness, which were extended later in Hindu, Buddhist and Jain thought.

But the first boom in popular “scientific” psychology thought was in the 20th century, with the mainstreaming of Freudian analysis. Its ubiquity was such that the idea of the “Id” played a large role in 1956’s science fiction blockbuster The Forbidden Planet. Freudian analysis also became chic and fashionable in psychotherapy, with the emergence of psychoanalysis. But despite his attempt to model a naturalistic understanding of the human mind, Freud’s ideas suffered from the same ailment as Marxism: an inability to be falsified. It explained everything, and therefore nothing. Rather than produce testable hypotheses, Freudian analysis was open-ended enough to allow for profuse and wild narrative creation, perhaps explaining why its lone 21st-century hold-out is in literary analysis.

An alternative to Freud’s theories was behaviorism, which attempted to understand the workings of the mind purely through empirical observation of inputs (stimuli) and outputs (behavior). If Freudian analysis was all theory about the mind’s working, behaviorism pulled back from any attempt to model and understand the mind a priori, simply observing the consequences of its operation in the world. Ultimately, behaviorism was a dead-end, just as pre-genetic attempts to understand heredity were unsatisfying. True science requires some model and mechanism to generate testable predictions. Instead of just observing patterns, you need to create a mechanism that can explain them.

In the 1950s and 1960s, psychology underwent a cognitive revolution, where a new theoretical understanding of the mind emerged, reconceptualizing it as a computing device with innate characteristics and biases. Modern scientific psychology and clinical practice must be understood in light of this paradigm shift, which brought insights from linguistics, neuroscience and computing into the field to produce a more holistic framework for understanding the mind's workings. In the wake of this paradigm shift, psychology was reborn as a discipline with two faces. A rationalist one, with an a priori understanding of the mind (contra behaviorism), and an empiricist one, with a focus on testable questions (contra Freudian analysis).

Since I am not a psychologist, I generally know the field through books. Luckily, psychology is a discipline with verbally adept scholars.

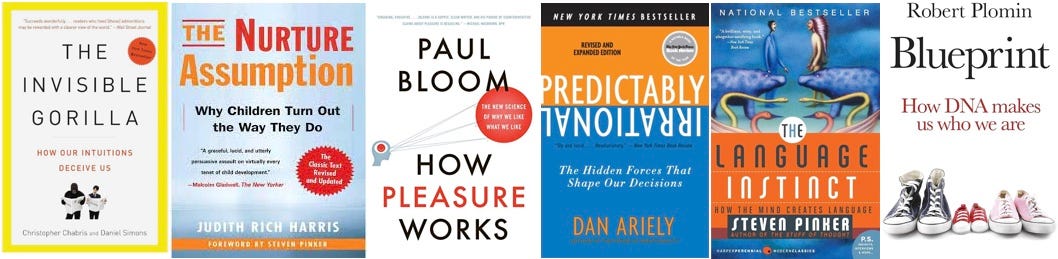

Steven Pinker, a friend of Unsupervised Learning, has written many books. But his first popular work, The Language Instinct: How The Mind Creates Language, is still one of his best. I remember plowing through this in the late 1990s, and suddenly understanding how evolutionary psychology and cognitive science could be done well. Language is one of the most important phenomena that define us as a species, and evidence from aphasia-sufferers indicates that our competencies exhibit localizations within the brain. Language is the perfect characteristic to apply the multidisciplinary toolkit of the new psychology, leveraging cognitive neuroscience, computer science and linguistics, to understand a human cultural feature that seems universal, with which almost all of us have competence, but which also varies so greatly between individuals. The Language Instinct is not the final word on “how the mind creates language” but it will open your mind to how we might eventually understand the process.

About a decade ago you could posit that Dan Ariely was on his way to becoming a Gen-X Steven Pinker. The author of several books, and a notable speaker and public commentator, his writing was engaging and lucid and tackled topics, like lying, that the public was interested in. Today though Ariely is under a cloud, as many wonder if most of his research in behavioral economics is sloppy at best and fraudulent at worst. But for a few years after the 2008 financial crisis, when mainstream economics seemed to have lost its way, Ariely was a prince of pundits. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions captures that moment in the late aughts when the whole intellectual space was being nudged in a new direction by the subtle psychology of priming and pushing. After the replication crisis, and now the possibility of widespread fraud in behavioral economics, this whole line of research is viewed skeptically. But, I think the truth is that understanding human biases can better equip you to grasp the reality of economic behavior in the wider world, than long-term stylized equilibrium models. Predictably Irrational is still a book to take seriously, if not literally.

If Ariely leaned into the irrationality and counterintuitiveness of psychological results, Chris Chabris and Dan Simons offer a more modest and cautionary tale in The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us. Though the book has a cognitive gimmick in the title, the invisible gorilla that people don’t notice, much of the narrative is devoted to correcting the enthusiasms of other psychologists about hidden forces in everyday life. The Invisible Gorilla didn’t get as much fanfare as many other books on psychology from this period, but it has held up because the scientist-authors were cautious in their predictions and skeptical of others’ grand claims. Chabris and Simons explain how intuitions deceive us, but they don’t construct a whole new paradigm on our ability to be deceived (no, implicit biases don’t rule us, no, you can’t really get smarter through brain teasers).

While Ariely, Chabris and Simons were writing about cognitive biases, a topic all the rage 15 years ago, Paul Bloom, then at Yale, was tackling a literally meatier topic, pleasure. Here Bloom likely runs into the issue where the potential audience is perplexed by why we need a scientist to explain a subject we all understand, but that’s what he does in How Pleasure Works: The New Science of Why We Like What We Like. On the one hand, human sensory pleasures are straightforward: we like fat and sugar. We like salt, and snuggling. But what about lobster? Today this is a luxurious treat, but a century ago it was poor peoples’ food. Similarly, in Japan whale meat is a delicacy, but a few generations ago it was the lowest quality meat, oily fare served in elementary school cafeterias. Bloom’s assertion, which seems robust, is that pleasure is more than simply immediate sensory impact. The narrative of a thing, the origin of an experience, all matter in how we perceive it (not only is whale meat expensive, it reminds rich older Japanese of their childhoods). If we think a glass of wine is $1000, we are liable to experience it differently than if we think it is worth $10.

If How Pleasure Works tackles a whimsical topic seriously, Robert Plomin’s Blueprint: How DNA Makes Us Who We Are tackles a serious topic with a light tone and breezy prose. That’s because Plomin, the doyen of contemporary behavioral geneticists, is giddy with excitement about where his field is and where it will go. With GWAS’s on the order of millions of study subjects and polygenic probing of intelligence and personality, the questions Plomin and his colleagues were asking decades ago are finally coming close to resolution all in a rush, and he’s exhilarated. Blueprint is somewhat of a maximalist take on the possibilities of behavior genetics; no half-measures here. But even if a bit too optimistic, it’s a vision of a future that’s coming at us fast.

Finally, I want to end with the late Judith Rich Harris’ The Nurture Assumption: Why Children Turn Out the Way They Do. This book popularized the reality that genes are the things you can control the most about your offspring, through mate selection. It turns out that on many behavioral traits most of the “environmental” component of variation is totally random; it’s not something we know anything about, so it’s not something we can plan for. Shared-family environment, which you can control, explains about 10% of the variation. Harris proposed that the remaining environmental component was peer groups, but over two decades later, there isn’t strong evidence of this from what I can tell outside of a few select cases, like accent and dialect. The main takeaway from The Nurture Assumption is that kids are robust, and genes matter greatly in outcomes. Ironically, it was published right before a major spike in helicopter parenting in American culture. Here is a case where I wish more people would just “trust the science.”

Thought

Blue states don't build The cost of stasis: population loss, homelessness, and reliance on fossil fuels. It’s great that states like Texas (where I live) and Florida exist because they are economically forward-looking, and serve as an escape value for young people trying to avoid high housing costs. There are also paradoxical facts like that Texas has far more renewable energy than California because the permitting regime is more liberal, in the literal sense. But a lot of human capital remains in California and New York. America needs to deploy this wisely, and the anti-development ethos of those regions is wasting a lot of talent as people scramble to find someplace to live rather than be freed up to focus on being productive citizens.

Chinese restaurateur’s rap video reinflames San Francisco mayor’s race. It’s interesting how and when racial representation and proportionalism come into play. Over the last 30 years, a black American has been mayor of San Francisco for 12, and an Asian (Chinese) American for six. As of 2020, San Francisco is 34% Asian American and 5% African American (the last Census year there were more blacks than Asian Americans in San Francisco is 1960).

The best pizza in America, from New York to Chicago to Los Angeles. Surprised to learn that more conventional “tavern-style” pizza is more popular in Chicago than “deep-dish.”

Did 1 Man Reproduce For Every 17 Women? I didn’t realize that people took that ratio literally! Apparently, it became an online meme. No, it wasn’t necessarily hyper-polygyny. Effective population is a weird concept. Important, but weird. Take it seriously, but don’t extrapolate literally. Different demographic situations can produce the same statistic.

Religion Among Asian Americans. Already a secular group, Asian Americans are growing even more so in the youngest generations. Recently I’ve noticed a lot of Korean Americans raised in the church are becoming irreligious, and switching from being Republicans to Democrats (Evangelicals are the only Asian American religious group that leans Republican).

The Patrilocal Trap. Western Europe avoided this ubiquitous social structure because of the social engineering of the Roman Catholic Church.

Game of clones: Science is immortalizing Argentina’s top polo horses. The future is here in the horse-cloning world.

Data

Accurate detection of identity-by-descent segments in human ancient DNA. “Here we introduce ancIBD, a method for identifying IBD segments in ancient human DNA…we reveal long IBD sharing between Corded Ware and Yamnaya groups, indicating that the Yamnaya herders of the Pontic-Caspian Steppe and the Steppe-related ancestry in various European Corded Ware groups share substantial co-ancestry within only a few hundred years.” There has been a long-standing argument about whether the Corded Ware Culture (CWC) of early Bronze Age Poland and the Baltic was deeply or recently diverged from the Yamnaya. These results indicate the latter and explain why Indo-Europeanists like Kristian Kristiansen and David Anthony emphasize the Yamnaya so much in their models of steppe expansion into Europe.

Population genomics of postglacial Western Eurasia. Two major points. First, there was a line in Eastern Europe where forager genetics from the Pleistocene were transformed to its west (replaced by Neolithic people), or maintained (continuity with earlier populations), to its east. The Yamnaya expansion 5,000 years ago overturned this equilibrium that had prevailed since the arrival of farmers nearly 10,000 years ago. Second, the interaction between the Neolithic Globular Amphora Culture (GAC) and Yamnaya to create the Corded Ware Culture (CWC) is something that needs deeper investigation, because it impacted most of the daughter Indo-European populations.

Pervasive selective sweeps across human gut microbiomes. Human gut microbiomes are adapting to our changing diets. No surprise theoretically, but in this preprint there’s an empirical test with a statistic. The microbiome is a big deal for our health, but there’s a lot of science that needs to be done.

Evolutionary trends of alternative splicing. How can you have so much biological diversity with only 1% of the human genome coding for proteins? First, I’m not sure 30 million genomic positions is a small number, but second, one of the answers given is alternative splicing. This is a molecular genetic mechanism where subunits of a coding genome are assembled differently, resulting in variable products. Just like an organism’s size or unique immune response, these molecular mechanisms are themselves interesting evolutionary characteristics.

One million years of solitude: the rapid evolution of de novo protein structure and complex. Very rapid evolution of new (de novo) genes from noncoding nonfunctional units. The intersection of molecular biology and evolution is great because it combines the biophysical concreteness of the former with the quantification of the latter. Here they find it is sometimes better and easier to get function out of new genes rather than leveraging gene duplication events (turning something used for one thing and targeting it at something different).

My Two Cents

There’s still no free lunch, free subscribers; my most in-depth pieces for this Substack remain beyond the paywall. In addition to re-releasing a trio of favorite past posts now with updated research, I’ve posted two original pieces in the past weeks:

When Slavs Rush in: the Fall of the Latin Balkans:

Perhaps the deep lesson here is that civilization and peace are rarely more than a sleek veneer, an eternal struggle against human nature, its tendencies toward faction and jealousy forever roiling just under any genteel surface. For three centuries, the Balkans furnished rulers of Rome who forestalled the Empire’s final collapse. They were born in the shadows of great cities like Sirmium, and would retire to ornate Adriatic palaces. Their home provinces were both physically on the frontier and militarily at the heart of the Roman world. But when the political and military order that sustained this civilization disappeared, withdrawn elsewhere, glory and greatness faded overnight. Into the vacuum marched illiterate barbarians from the north who knew nothing of Rome, but crucially were hardy enough to survive and flourish in the chaos. The simple, primitive culture of these newcomers was a refuge for the long-suffering common people lately abandoned by the Empire. To survive, Roman peasants adapted, throwing in their lot with pagan barbarians who at least offered an avenue to flourish within a new and less brittle system. Despite all of Justinian’s learning and polish, in fact when you scratched an average Illyrian, the doughty savage appeared just beneath the veneer, endowed with an indomitable spirit of survival, whether his age was ordered around emperors, law and sophistication, or knew not a trace of any of the above.

More than kin, less than kind: Jews and Palestinians as Canaanite cousins:

The Jews’ return from Europe in larger numbers in the early 20th century was the homecoming of people who had evolved and changed genetically via the assimilation of neighbors drawn from gentile majorities, in particular gentile women who followed in Ruth’s footsteps. But these people’s self-conception was firmly rooted in Middle Eastern Judaism, with a religious life that centered around the Babylonian Talmud. Though only a minority of Ashkenazi ancestry is Levantine, their continued adherence to a Jewish identity goes back to Jacob and his sons. Their own identity is the identity of these ancient Levantine patriarchs, liminal figures at the threshold of recorded history. In contrast, while Palestinian Muslims are mostly Levantine in their blood and most of their ancestors were certainly likely to have been Jewish in 300 AD, their meme package has drawn them away from this ancestral birthright. And despite the native Palestinian biological kinship with the Ashkenazi migrants, a line of ancestry converging back into one less than 2,000 years ago, the two groups were to become the late 20th and early 21st centuries’ ultimate antagonists, their very names, when joined, bywords for conflict, strife and irreconcilable interests.

Discussion

All my podcasts go ungated two weeks after their Substack release. So I encourage subscribers on the free plan who’d like to automatically get them to subscribe to that podcast stream (Apple, Stitcher, and Spotify). If you want to listen on YouTube, please subscribe.

Here are my guests (and monologue topics) since the last Time Well Spent:

Cesar Fortes-Lima: the three thousand-year odyssey of the Bantu

And here are the currently ungated podcasts all in one place.

For subscribers, I post transcripts (automatically generated, though I have someone going through to catch major errors).

ICYMI

Some of you follow me on my newsletter, blog, or Twitter. But my own domain also has all my links and updates: https://www.razib.com

Over to you

Comments are open to all for this post, so if you have more reading/listening suggestions or tips on who I should be talking to or what you hope I’ll write about in 2024, lay it on us.

Razib, I'd be interested in a podcast with Peter Gray of the Play Makes Us Human substack, if you can get him on.

I enjoyed reading the history of Slavs. My great grandparents came from Eastern Europe. I have heard here and there Slavs and Hungarians weren't considered white at one time and I'm starting to read more about that.

I'm a free subscriber on a tight budget at the moment, so I couldn't read everything. Perhaps in the future I can upgrade.