RKUL Hit List 2023: From deepest Siberia to Europe’s edge

Revisiting favorite Substack pieces, with research-based revisions

The main project of this Substack is writing the first drafts of newly genetics-informed human population histories. Over the past two decades, genomics has been deluged with manifold riches on an absolutely staggering scale. Computational power, DNA extraction scale (especially from ancient samples) and widespread affordable consumer testing have all gone from intangible pipe dreams to tearing through phases of literally exponential growth. Our powers have risen multiple orders of magnitude in the last 20 years. I have been an excitable front-row commentator on the genomic revolution from the perch of my original blog for two decades now, but this new project of systematically covering what we thought we knew of human history and population movements versus what genomics can confirm or rule out is only a little over three years old for me.

The first full year I published this newsletter, 2021, I began diving into reflections on some of my top favorite historic and prehistoric human populations. People were paying me to write about my favorite stories; I went straight for my own canon of greatest hits first. But I had no idea whether this mailing list would keep growing and most of you weren’t here yet. These are some of the richest human stories I know and only a select few insiders were reading those first drafts. An exciting thing about writing up papers in human population genetics as they’re released… is that as spot-on as they might prove, they’re rarely the last word. Exciting or plot-twisting addenda and further details are always likely to appear around the bend.

So, as the third full calendar year of this Substack draws to a close, I’m revisiting three of my favorite past posts, updating them to reflect the assorted subsequent findings I’d include if I were first writing those drafts today. This is part of my six-part series on the Finns published in the summer of 2021. I selected this chapter to update because some important substantive changes about the origins of the Finns have come to light (bolded). Those research-driven updates sharpen our narrative about the origin of the Finns, and clear the way toward understanding Inner Asian prehistory with much greater granularity. Originally sent to 1,190 paid subscribers, this revised piece goes out to some 39,000 total free and paid subscribers.

Again, for all who have previously read it, today’s updates appear in bold so you can easily scroll between them.

This is the fourth in a six-part series.

Part one: Duke Tales: shades of Finnish cultural weirdness in my own backyard

Part two: Weirdness as a national pastime: culture

Part three: Go West Young Siberian: genetics findings

Part five: Frontier Finns: cabins, rakes & Indians

Part six: Finnish brains, baiting and bottlenecks

Between early inferences from skull morphology and transparent linguistic affinity to Samoyedic dialects of Central Siberia, scholars once entertained theories of an immense genetic gulf between Finns and their European neighbors to the west and the south. It is notable that during World War II the Nazi regime opened lebensborn centers for young women to bear pure Aryan children of SS officers in occupied Norway but not allied Finland. Today, using the massively more powerful and precise tools and techniques of modern genomics, we can verify that native Finnish people actually average only 10% Siberian in overall ancestry (despite the fact that linguistically, Samoyedic is far closer to Finnish than Swedish). Estonians, whose language strongly resembles Finnish, are a smaller fraction still, likely due to long-term interaction with Slavic and Baltic Indo-European-speakers to their south and east, who diluted the original Siberian fraction. In contrast, the Saami, who occupy the more impenetrable lands of the north, and seem to have originally been present much further south until the Finns pushed them out, are as much as 25% Siberian. Clearly, the genetic imprint of these outsiders is far more modest than their cultural influence.

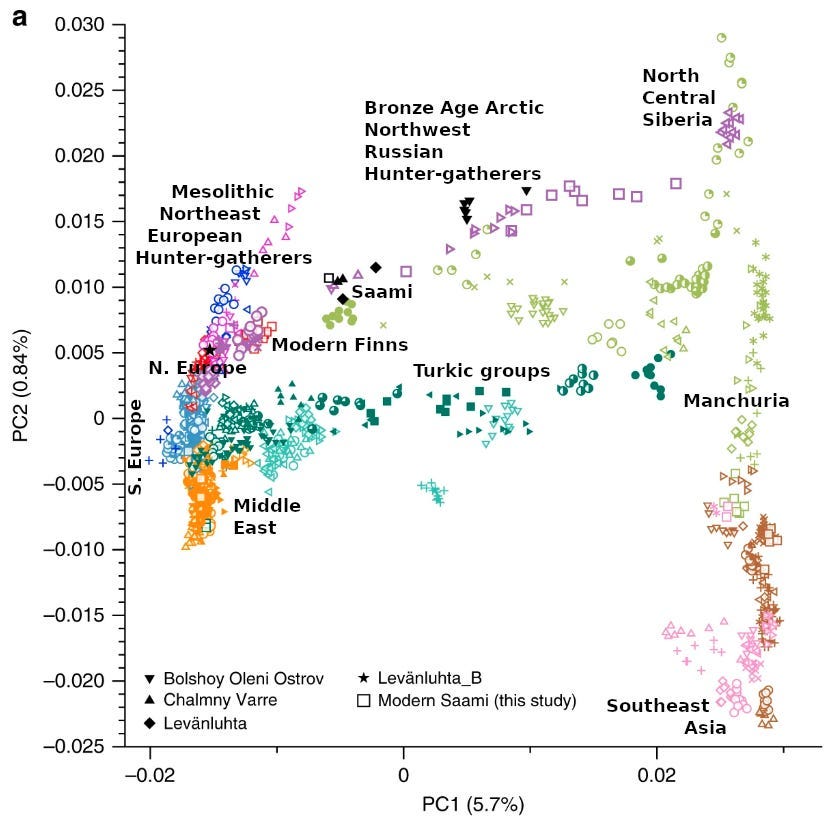

So, who were these Siberians? And when did they arrive? The distribution of their Y chromosomes lightly dapples a vast area of Northern Eurasia to the east of the Baltic, stretching all the way to the Pacific. The paternal lineage of Finns groups them with Turkic-speaking Yakuts in eastern Siberia. But a quick inspection of the genetic plot above, which uses the whole genome, suggests that the Finns, and to an even greater extent the Saami, are shifted in the direction of ethnic groups which occupy a narrow zone of northern-central Siberia. These are the Nenets, Ngannasans, and Selkups, the Samoyedic tribes. The exact same tribes Matthias Castrén spent his last years studying. The exact same tribes that speak the most eastern Uralic dialects. So the Siberian ancestry component of the Finns and their closest relatives comes, no surprise, from the Siberian tribes which speak languages related to Finnish. It is not the first time and it will not be the last that geneticists work long and hard to climb the mountain, only to find that linguists have beaten them to the punch.

Occupying the lands just to the east of the Ural mountains, the Samoyedic tribes had a clear path to Europe by skirting the forbidding fringe along the Arctic shores. What might seem a frozen wasteland to us was simply the great northern highway, the path of least resistance west, for Siberian foragers. A permafrost tundra that they became adept at exploiting (perhaps too adept, judging by the megafaunal extinctions of the ice age).

The First Nordics?

Until we had ancient DNA, the timing and nature of these Siberians’ arrival remained supposition and suspicion. While some scholars, looking to historical linguistics, argued for a model of recent Baltic settlement by Finnic-speaking people around 3,000 years ago, others insisted on a period much deeper in time, the Mesolithic, 6,000 years ago. During the Mesolithic, the whole swath of territory between Finland and the Urals was dominated by what is termed the “Comb Ceramic Culture” (CCC). CCC settlements get their name from the prevalence of remains of large vessels inscribed with comb-like impressions along their surface.

Despite its ubiquity in Northeast Europe, the earliest comb-impressed pottery is actually found in Manchuria over 6,000 years ago, pointing to eastern connections. What we know of the CCC suggests they were an advanced hunter-gatherer culture distinguished by their mobility across Northern Eurasia, and they spread westward from the east, finally coming to rest at the shores of the Baltic. This made them a natural candidate to be the elusive proto-Finns. As the CCC presence in Northern Europe predates the expansion of Indo-European languages, the thesis was congenial for nationalists as well, as it testified to the cultural indigeneity of the Finns in the Baltic. If the CCC spoke Finnic languages, then these dialects would date back to the arrival of Scandinavians in lands to the west and Balts in those to the south. The Finns could be considered aboriginal to the region, its O.G. settlers.

Though we can’t ascertain what language the CCC spoke with certitude, ancient DNA has established their genetic affinities. Their Y chromosomes are never N1c, and their genomes show no evidence of recent ancestral connections to East Asia, two of the tell-tale diagnostic features of the Finnic populations in Northeast Europe today. The CCC descended mostly from “Eastern Hunter-Gatherers” (EHG), a catchall set of varied peoples who occupied the vast and lightly settled territory to the east of the Baltic and west of the Urals after the last ice age. Most EHG ancestry was actually shared with Pleistocene Siberian populations even further east, beyond the Urals, whose reach extended to the Pacific Ocean and ended up contributing about 40% of Native American ancestry.

Nevertheless, EHG populations lack any genetic ties to modern East Asian groups with connections to Siberia, particularly those in Manchuria and Northern China. Despite its harsh climate, Siberia has been subject to migration out of Manchuria and Mongolia several times, and its current inhabitants’ genetic heritage is a complex layering of “Paleo-Siberian” ancestry dating back to the arrival of modern humans (the component also found in the EHG), with “Neo-Siberian” heritage connected to movements out of East Asia over the last 15,000 years. The distinct Siberian ancestry in Finns indicates recently shared heritage with East Asians, unlike the Paleo-Siberian connections of the CCC. This definitively rules out the Mesolithic foragers as a source of Siberian ancestry in the Baltic.

Eventually, the conveyor belt of archaeological cultures moved on, and farming did arrive in Northeast Europe. By 2500 BC, the region was host to the arrival of the Corded Ware Culture (CWC). The CWC were almost certainly Indo-European speaking, with origins in the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea, though 25% of their ancestry also derived from the Neolithic Globular Amphorae. In Scandinavia, the CWC begat a local variation, the more charismatically named Battle Axe Culture. Having hopped across the Gulf of Bothnia, the Battle Axe people occupied the southern and western coasts of modern Finland (leaving the vast interior to foraging populations presumably descended from the CCC). The new people replaced their Neolithic predecessors in prehistoric Scandinavia with no genetic hybridization. The mechanism of this replacement is not a great mystery. Some anthropologists have hypothesized the battle axes of these people were purely ceremonial, but numerous defensive palisades of the last Neolithic people were likely a reaction to the violence of the invaders.This prefigured the violence of the later invasion of crusading Swedes, who contributed our first written records of events in Finland.

Like the CCC who preceded them, the Battle Axe males were not N1c. Rather, haplogroup R1a1a defined the Battle Axe males. Among the Finns living in former Battle Axe lands today, fewer than 10% of men carry R1a1a. In fact, the Y-chromosomal profile of modern Finland is strikingly simple: 60% N1c, 30% I1, and the remaining 10% or less shared between sibling rivals R1a1a and R1b. R1b is also associated with western Indo-European speakers, while I1 is common across Scandinavia, and expanded with the spread of proto-Germanic around 1800 BC.

Bronze-Age Finland saw the arrival of Scandinavian-speaking Indo-Europeans, but it was a false dawn. Genetically, these people contributed most of the ancestry of modern Finns, but culturally, they were pushed aside and superseded by later arrivals, the Siberian-origin ancestors of the Finns.

Getting warmer

In the last few years, ancient DNA has finally answered when and who brought Siberian ancestry to Northern Europe. Bounded in the west by northern Finland, and in the east by the Barents Sea, the tundra-covered Kola peninsula juts like the bulbous paddle of a beaver's tail out into the Arctic ocean. It is here, where the base of the paddle meets the rest of the beaver, if you will, on inlet-sheltered Bolshoy Oleny island, that the remains of six individuals who lived 3,500 years ago have yielded the earliest indications of Siberian ancestry in Northern Europe. These Bolshoy individuals were over 45% Siberian, far more than we see in the modern Saami. And by Siberian, I mean ancestry that connects them clearly and directly with modern populations in East Asia, in Manchuria and Northern China. Most of the rest of the Bolshoy ancestry was EHG, the component dominant in the Mesolithic CCC. This suggests that as Manchurian-related foragers drifted north and west, they mixed extensively with indigenous Paleo-Siberians, and further west, with EHG.