More than kin, less than kind: Jews and Palestinians as Canaanite cousins

The cold facts recorded in Jewish and Palestinian genetics today and historically

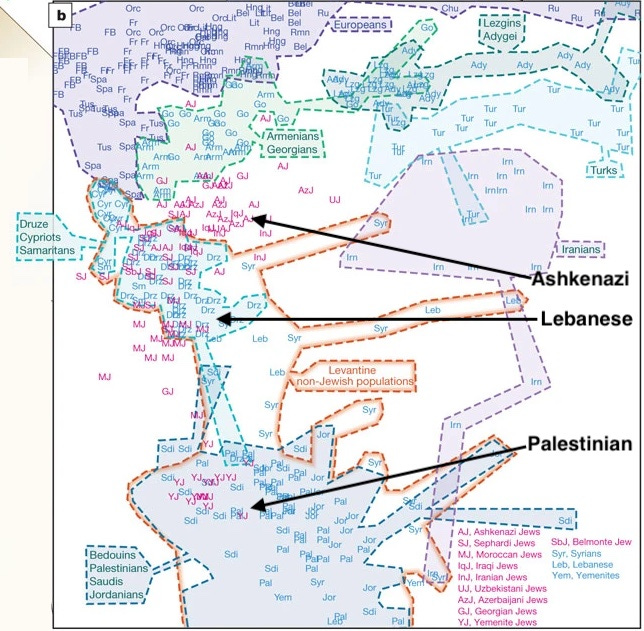

The years around 2010 saw a spate of publications using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) array data to map the population genetics of various Jewish groups, as well as their relationships to non-Jewish populations. The figure above is a principal component analysis (PCA) that appeared in one of the papers, The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people. Given the emerging affordability of data generation, with hundreds of thousands of markers per individual suddenly available on a typical late 2000’s grant allocation, geneticists could finally get a precise sense of the relationships of many of the world’s populations and confidently settle what had been contested questions. Published in Nature, the paper received widespread media attention and set the terms for our updated understanding of Jewish population genetics, as reflected in books like M.D. Harry Ostrer’s 2012 Legacy: A Genetic History of the Jewish People.

The paper’s authors found, unsurprisingly, that the Ashkenazim, Northern European Jews, were a mixed population, with both European and Middle Eastern ancestry. At the same time, Middle Eastern Jews, whether Sephardi (from Morocco, Egypt, Turkey, Greece and Syria) or Mizrahi (from Iraq and Iran) or Yemeni, were by and large more (Mizrahi) or less (Sephardi) similar to other Middle Eastern populations. Our understanding of Ashkenazi ethnogenesis through genetics has only grown in sophistication in the decade since, but in broad strokes, the relationships first illustrated in the PCA above still hold. Subsequent papers further falsified theories like Shlomo Sand’s 2008 contention in The Invention of the Jewish People that the Ashkenazim descended solely from European and Central Asian converts, or on the other hand, the assertion that the Ashkenazim were entirely a Middle Eastern people, with no biological connection to other Europeans.

But now, over a decade later these scientific findings are belatedly gaining wider visibility. In recent months, since Hamas’ 10/7 atrocities and Israel’s subsequent bombing and invasion of Gaza, individuals and institutions I have never previously seen offer population genetics explainers are brandishing figures from these decade-old papers, and spinning them to further their agendas. Several times, I have seen the PCA above deployed to show that Palestinians are settlers, descended from Arabians, due to their proximity to Saudis in the plot and distance from other Levantines, like Lebanese Christians. Israel partisans note that Ashkenazi Jews appear closer to Lebanese populations in the visualization above, implicitly drawing a picture where they are indigenous, inverting the anti-Zionist narrative. Yet others can be found flogging more recent findings that show through whole genomes, ancient DNA, and computationally sophisticated model-building, that Ashkenazi Jews are “only” 10-40% Levantine (the balance of their ancestry being Southern and Northern European). The takeaway from these arguments, where Ashkenazim are less than 50% Middle Eastern, is supposedly that Israeli Jews are invaders to the region, primarily European-descended, and in no way rooted in Palestine (non-European Jews, who make up at least half of Israel’s Jewish population, are pointedly ignored in these gotcha posts).

I have not been tempted to join these conversations nominally about a field I know well because for the most vocal Twitter-famous and various newly minted historians, archaeologists and geneticists, the thrust of the exercise is purely political, not scientific. The reality is that all the genetic results in the world will neither sway the most impassioned polemicists nor impact the conflict on the ground. Science is being cynically drafted into a forever culture war; any pretense of principled truth-seeking, or quest for a foundation for deeper understanding, rings hollow.

And yet, again and again, since October, correspondents have been reaching out to earnestly ask me what the real scientific consensus is, sans partisan spin. Until now, I have just responded privately. But months into this, I recognize that it is not just those who know me well enough to ask privately who would appreciate just getting the cold, hard scientific consensus from someone professionally obsessed with data, shorn of the heated rhetoric of human feelings and historical passions. So, here is my attempt to cover the late 2023 state of understanding of Jewish and Palestinian genetics without sophistry or motivated reasoning, to simply revisit what science has and has not found thus far.

What can be settled?

First things first. I’m not delving into this to convince anyone of anything or provide anyone with ammunition. Facts exist regardless of current geopolitical exigencies or our intense feelings about them. The goal here is simply to review what facts are settled in the field today in light of rapid increases in genomic technology. But before we dive into any analysis, we need to agree on what kinds of questions can even be meaningfully answered by the combination of modern and ancient DNA samples analyzed through genomics and the population genetic methods of analysis currently available to us. With every awareness that exactly zero matters of policy or political minds will be changed on principle because of what we find in the DNA, here are the questions I think we can hope to meaningfully answer given the data and tools at our disposal today:

Are Palestinians descended from invading Arabs (circa 650 AD), native pre-Islamic peoples of the region (or a mix)?

Are Jewish Israelis today native to the Middle East (specifically Judea), Europe, elsewhere, or a mix?

Who is genetically closest today to the inhabitants of Judea circa 2,500 years ago?

First, a single representation or model of genetic variation, like extrapolating excessively from the PCA above in isolation, is not considered best practice in 2023 (we did what we had to do in the 1990’s, dial-up modems and all). Not only do population geneticists now have vast troves of data to query, they also have many more and far richer analytic methods to deploy, enabled by vastly greater computational power accessible to both professional researchers and amateur enthusiasts. A single method is not definitive or dispositive when the questions are multi-layered and the reality of the population-genetic history is complex; a reticulated lattice as opposed to a branching tree.

Consider a mixed African and Northern European population (two very genetically distinct groups) whose composition is the outcome of an approximately singular admixture event, like African Americans. In this case, a PCA, which represents the relationships between individuals in the population, is still sufficient. So is simply checking the aggregate genetic distance between the two endogamous populations by looking at the overall genetic variation and teasing out the proportion of the variation that differentiates the two groups.

But in the case of the Middle East and Europe’s history, and the populations that have emerged there from various admixture events over the past 10,000 years, that won’t cut it. The PCA neutrally represents what interrelationships it finds, but historically, these individuals have derived from complex interactions and an extraordinarily long and repeatedly intertwined and tangled history. The results themselves can’t be contested (they’re just mathematical representations of eigenvectors and eigenvalues that fall out of the variation specific to a linear model), but numerous underlying scenarios could fit them. And, it always bears remembering that analyses are representations of the raw data designed to make it more digestible for humans to understand and interpret; they’re not the underlying data itself (which in its simplest form is just trillions of A’s, C’s, G’s and T’s).

Today, with a surfeit of data, ancient DNA, and more sophisticated modeling, we are much closer to concluding “how” the relationships observed in the 2010 Jewish genetics papers came to be. And it is the how that truly gets at the knotty issues of who is a settler and who is a colonist; who descends from whom millennia ago. But first, let’s examine populations from that paper with other methods and see how their genetic relatedness and clustering patterns look with some different methods (happily, the authors of that research group routinely make their data public). This will equip us with a better sense of the relationships of the present-day populations beyond a PCA and set us up to dive into the past.

For this analysis, I assembled a dataset with many of the same populations in the PCA. I merged samples from the 2010 paper of mainly Middle Eastern and Jewish populations, with others drawn from both the Human Genome Diversity Project and 1000 Genomes. After quality control, where I culled both what were clearly close relatives and any SNP positions that were missing in the dataset at rates over 1%, 799 individual samples sharing 123,530 markers made the cut.

A PCA is a traditional way to represent variation by breaking down the rows and columns (individuals and each of their hundreds of thousands of markers in text formats) into a set of independent dimensions that capture the data’s underlying patterns of genetic structure (each individual has a value in each dimension, so it is easy to map onto a two-dimensional plot with axes as the dimensions). However many other ways to represent and interpret genetic variation exist. A pairwise Fst is a method that’s been around for decades (you already see it in L. L. Cavalli-Sforza’s 1994 book The History and Geography of Human Genes). It compares the distances between populations as collective units rather than within the set of individuals. Running this method on the Middle Eastern and Jewish populations in my data exposes patterns that will not surprise those familiar with the most recent population genetic work on these populations. Sephardim (those Jews with origins in Spain), Moroccan Jews (whose ancestry is again mostly Sephardic), Italian Jews and Ashkenazi Jews are all on the same branch as the two non-Jewish Italian populations, indicating low genetic distances and high relatedness. This is expected; the best current models imply that European Jews, Sephardim (originally from Spain) and Ashkenazim, have a lot of ancestry from an ancient Italian population. As my friend Taylor Capito likes to say, Italians don’t look like Jews, Jews look like Italians. Also, unsurprisingly, some regional Jewish groups are very genetically similar to their nearby non-Jewish neighbors. The Syrian Jewish samples resemble many Middle Eastern groups. The Jews of Kurdistan look very similar to Iranians. The Jews from Yemen, in southern Arabia, are on a branch with Saudis.

There are also notable patterns for non-Jews. Iraqis, Syrians, Jordanians and Lebanese Muslims share a branch, set apart from Lebanese Christians, Lebanese Druze and Palestinians. The Druze are a sect with origins in Islam but they have been endogamous since the 12th century AD. Palestinians land closer to Egyptians than to the Lebanese groups, supporting the common conjecture that many Palestinians (like the late Yasser Arafat) have recent Egyptian ancestry.

But we should be careful again of overreading from one visualization that is rooted so heavily in summarizing the texture and detail of the data into a single number. PCA and pairwise Fst aggregate all the variation in the data to represent individuals or populations as a single set of values that attempts to represent their total ancestry, a summary of the histories of 19,000 genes, each with distinct stories. To understand better what’s going on, model-based clustering representing individuals on bar charts is useful, because it breaks apart the genome of a single individual into distinct components (each individual appears as a slender stratum, their horizontal line broken up into color-coded elements representing ancestry fractions). If someone is African American, rather than just floating somewhere between Europeans and Africans on a plot, they are given a proportion of ancestry, like 82% European and 18% African. More nuance might emerge; for example, someone might be 50% European, 40% African, 5% East Asian and 5% Native American. The more complex a region’s population history, the less simple summaries like PCA and Fst serve our understanding.

Are Palestinians descended from invading Arabs or native pre-Islamic peoples?

To break down individual ancestries, I ran model-based clustering with Admixture, assuming five ancestral populations in the data. This means that all the individuals within the dataset can be represented as combinations of the (at most) five putative ancestral populations in the model against which the genomes are tested. Included are outgroups like Lithuanians (proxies for Northern Europeans), Dai (for East Asians) and Nigerians (for Africans), to tease out those three broader continental population clusters. I also generated a tree representing the genetic distance between the hypothetical clusters to make it clear these components are not all equivalent in how they relate to each other (among the five clusters, some are more genetically similar to others). The figure above, and the two figures below all come from the same clustering run.

For the sake of clarity, I will refer to the clusters, or K’s, in the shorthand of approximate geographical/ethnic identifiers. Dark blue is Arabian, light blue is Northern European, gray is Iranian, orange is Asian and yellow is African. The admixture results immediately offer a simple explanation for why in the PCA of the 2010 paper the Palestinians were shifted toward the Saudis: they have African ancestry, and the Arabian cluster that is maximized in the Saudis is itself closer to the Nigerian African cluster genetically on the pairwise Fst representation. In other words, any African ancestry in Palestinians will also move them on a PCA toward Saudis even without direct Saudi ancestry per se.