When Slavs Rush in: the Fall of the Latin Balkans

From Roman grandeur to the dawn of the Slavs

The 6th century Emperor Justinian the Great was known as Ultimus Romanorum, the “Last of the Romans.” Ruling from Constantinople, modern Istanbul, he presided over the Roman Empire’s end and the Byzantine one’s beginning. Though he rose to power as Emperor in the east, much of Justinian’s fame owed to restoring Imperial rule in the west, across Italy, North Africa, southern Spain and France. He was the first emperor since Theodosius the Great, over a century prior, to truly rule nearly the entire Mediterranean, from the Straits of Gibraltar to the shores of Syria. His legacy of Imperial political and military interests in the West would persist for over five centuries, with the last Byzantine domains in Italy finally falling to Normans only in the eleventh century AD.

Though Justinian’s grand sobriquet was a legacy of his ambition to restore the Roman Empire, it was not the sole reason to call him the last of the Romans. He would also be the last Emperor who grew up natively speaking Latin. But Justinian was hardly a native son of Italy. Born Petrus Sabbatius, he came into the world in Tauresium, 700 miles from the Roman forum as the crow flies, in North Macedonia, 70 miles north of the Greek border (though his family’s ultimate origins seem to have been in what is today Serbia). And yet, Latin was indeed Justinian’s mother tongue. Why?

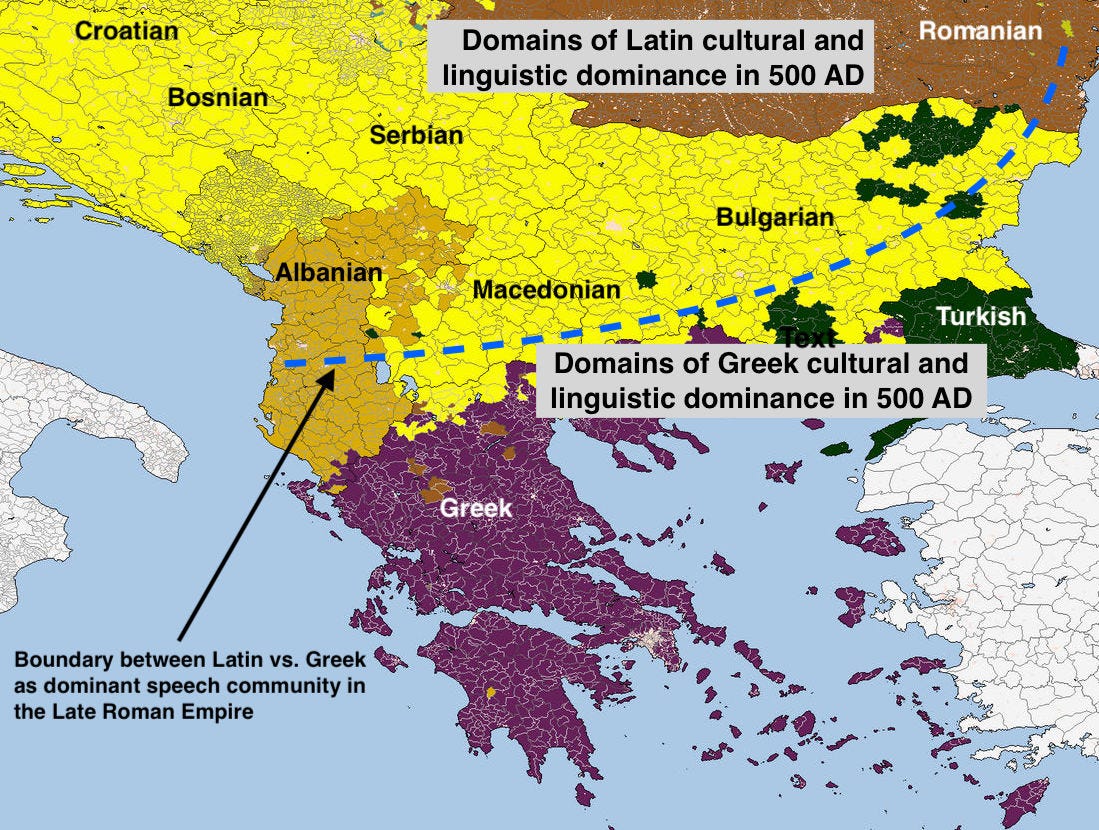

The background is simply that when the future Emperor was born, in the late 400’s AD, the Balkan peninsula, just like Italy, was mostly a domain of Latin speech. There were exceptions: Greece remained Greek-speaking, obviously, and Albania’s mountainous hinterlands, then called Epirus, were so isolated that native Illyrian speakers still predominated there. Greek was also the lingua franca in southeastern Thrace, in the local penumbra of Constantinople. But the remaining 75% of the Balkans was the realm of Latin, a language that had spread with the Roman Empire and its legions south of the Danube just as it had in provinces of Italy’s west: Gaul, North Africa, Britain and Iberia.

And this reality of a Latin Balkans is not some historical trivia about an inconsequential backwater of the grand empire. For three centuries after 249 AD, 90% of the time the Roman Emperor was either a Latin-speaking man born in Illyria, a region encompassing much of modern Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia and northern Albania, or was of Latin Illyrian ancestral origin. The first Illyrian was Decius, who became Emperor in 249 AD and hailed from modern Serbia, while the last was Justin II, Justinian’s nephew who reigned until 578 AD. These “Illyrian Emperors” pulled Rome through the Crisis of the Third century, decades when the Empire seemed perennially poised on the brink of irredeemable political division. The Illyrian emperors decisively reconstituted the state into the Dominate. This autocratic and despotic regime was a highly militarized tyranny, and maintained vigor by systematically promoting officers of modest rank but demonstrated competence. Great talent could clear a path to the heights of power, even all the way to the purple. Emperor Justin I, Justinian’s uncle, was likely the first in his family to rise out of the peasantry (on account of which you can find what are probably baseless accusations that he was the lone illiterate Roman Emperor).

And yet today, memory of these decisive centuries of Illyrian soldier Emperors, sons of peasants and artisans, fades to near invisibility alongside the enduring glitter and glow of the Julio-Claudians and their storied exploits, from Augustus’ conquests to Nero’s perfidy, or the wise Antonines, typified by stoic Marcus Aurelius, and even the infamously perverted Elagabalus in the early third century (by exception, of the Illyrians, Constantine the Great and Justinian alone are widely recollected today; both greatly transcended any specific Illyrian origin, Constantine adopting Christianity and Justinian reviving the Roman Empire).

One reason for this selective amnesia may be that Latin Illyrians left no deep cultural legacy across the territories from which they originally sprang. Today, aside from Albanians, the western Balkans are inhabited solely by Slavic speakers. Dalmatian, a Romance language of the Adriatic coast and the last in the region with any elite purchase, went extinct in the early modern period while Romance-speaking shepherds called Vlachs are marginalized pastoralists who wander as aliens in the land of the South Slavs. Arguably, modern Romanians, who speak a Romance language, are the singular remnant of the extinct world of the Latin Balkans. And yet, curiously, this language’s range today lies almost entirely outside the Roman Empire's post-300 AD boundaries, which ran only to the Danube River. Romania as a nation-state is of recent vintage, a child of modernity. Romanians’ ancestors have a clear linguistic connection to the Latin-speaking population of antiquity, but those Roman peasants disappeared from the written record for centuries, plunged at length into a depressed and invisible status by their Turk rulers, only fitfully reemerging into the light of history.

Though moderns often fixate on the fall of the Roman Empire to the point of cliche, that obsession rarely goes beyond the prism of key events in the West, from Rome’s 410 AD Gothic sack to Britain’s 6th-century annexation into the pagan Germanic world. And yet the reality is the Christian Goths left Rome itself relatively unscathed, while Latin Britain in 400 AD was a marginal and isolated province that produced not a single emperor. Roman Britain is remembered because it was once integrally part of Classical civilization, despite lying at the known world’s far edge; Bath’s great ruins bespeak the fullness of Romanitas as powerfully as anything in Italy. But with the Empire’s fall and the withdrawal of its legions, Britain slipped from the orbit of history and back into myth, a blank slate ripe for the fancies of Arthurian legend. At a stroke, Anglo-Saxon arrival in Britain erased language, religion and even the memory of the Roman past. While Gaul, Italy and Iberia fell under barbarian rule, in each case, eventually the new rulers were culturally co-opted, adopting the Romans’ language, religion and even titles. Though Islam’s rise would peel the Mediterranean’s southern and eastern shores away from the Roman religion, historian Chris Wickham argues in 2009’s The Inheritance of Rome that the seventh-century Arab Caliphate should properly be thought of as true heir to the Imperial Roman political tradition, rather than a radical cultural rupture (the Umayyads retained Greek as their administrative language until 700 AD).

But it was in the Balkans, whose central role in the Empire was forgotten in Renaissance Western Europe’s fevered 15th-century rediscovery of antiquity, that the Roman legacy was overturned most decisively. What had been the beating heart and strategic head of the late Roman world, the lands from whence Justinian the Great himself had emerged, fully slipped from Imperial control within a century of the Ultimus Romanorum’s 565 AD death. The Illyrian city of Sirmium, one of the four capitals of the Empire in the late third century Tetrarchy and birthplace of ten Roman Emperors, is today the modest and obscure Serbian town of Sremska Mitrovica, population 74,000. What was once the easternmost extension of the Latin world out to the Black Sea is now firmly oriented to the east, a realm of Orthodox Christian Slavdom in the Balkans.

The story of this transformation is one of collapse, degeneration, migration and rebirth into something totally new. The Roman Empire, seen as eternal and permanent by its citizens, fell with the 476 AD abdication of Rome’s last Emperor. But in the 6th century, Justinian restored a unified Empire, only for it to collapse under the weight of barbarian migrations into the Balkans and Islamic conquest in the early 600’s. The end of Latin Balkan civilization testifies to the impotence of recorded laws executed by venerable institutions when faced with a fallen world, where barbaric tribes offer the stark choice between assimilation and extermination.

The Fall of Civilization and the Rise of the Slavs

In Justinian: Emperor, Soldier, Saint, Peter Sarris argues that Italy and North Africa’s conqueror actually viewed himself more as a religious thinker and cultural reformer, laying the groundwork for an Orthodox Christian Byzantine civilization that would outlast his reign by nearly 900 years, until Constantinople’s 1453 AD fall. Though from a modest background, Justinian was both literate and cultured, nursing an interest in theological disputes that raged across the Empire, and pushing forward the construction of the Hagia Sophia, an architectural wonder that would remain the largest church in the world until the 1520 AD completion of the Seville Cathedral, nearly a millennium later. The Illyrians were at the center of Roman culture and politics for the final chapters of its existence.

At the same time, far to the north, the Roman world first encountered the Slavs, barbarians from the fringes of the Baltic, previously unknown to the people of Classical Antiquity except as rumors and legends. In The History of the Wars, Procopius, the great annalist of Justinian’s reign records the first detailed anthropological observations of these people who would loom so large in later European history. He notes that these barbarian pagans organized themselves in small bands and roamed from place to place like nomads. They had chiefs, but their social and political structure was egalitarian and primitive. Unlike the Romans, they did not mobilize expensively outfitted, heavily armed cavalry or deploy in tight, disciplined infantry formations, instead preferring irregular guerilla combat with light arms like javelins. These pagan Slavs persisted in their Iron Age, small-scale lifestyle for centuries, refusing to organize into larger tribes until forced to by others. They were finally marshaled in large numbers under the leadership and hegemony of Turkic nomads, first Avars and then Bulgars. Procopius also makes physical anthropological observations, reporting that the Slavs were tall and of ruddy complexion.

And yet it was these rustic Slavs who absorbed the Latin-speaking people, former citizens of the world’s greatest empire. Not only did the simple people Procopius described integrate the common Romans who remained in the lands conquered by barbarians, they also eventually absorbed their rulers, the Turkic Bulgarians and Avars.

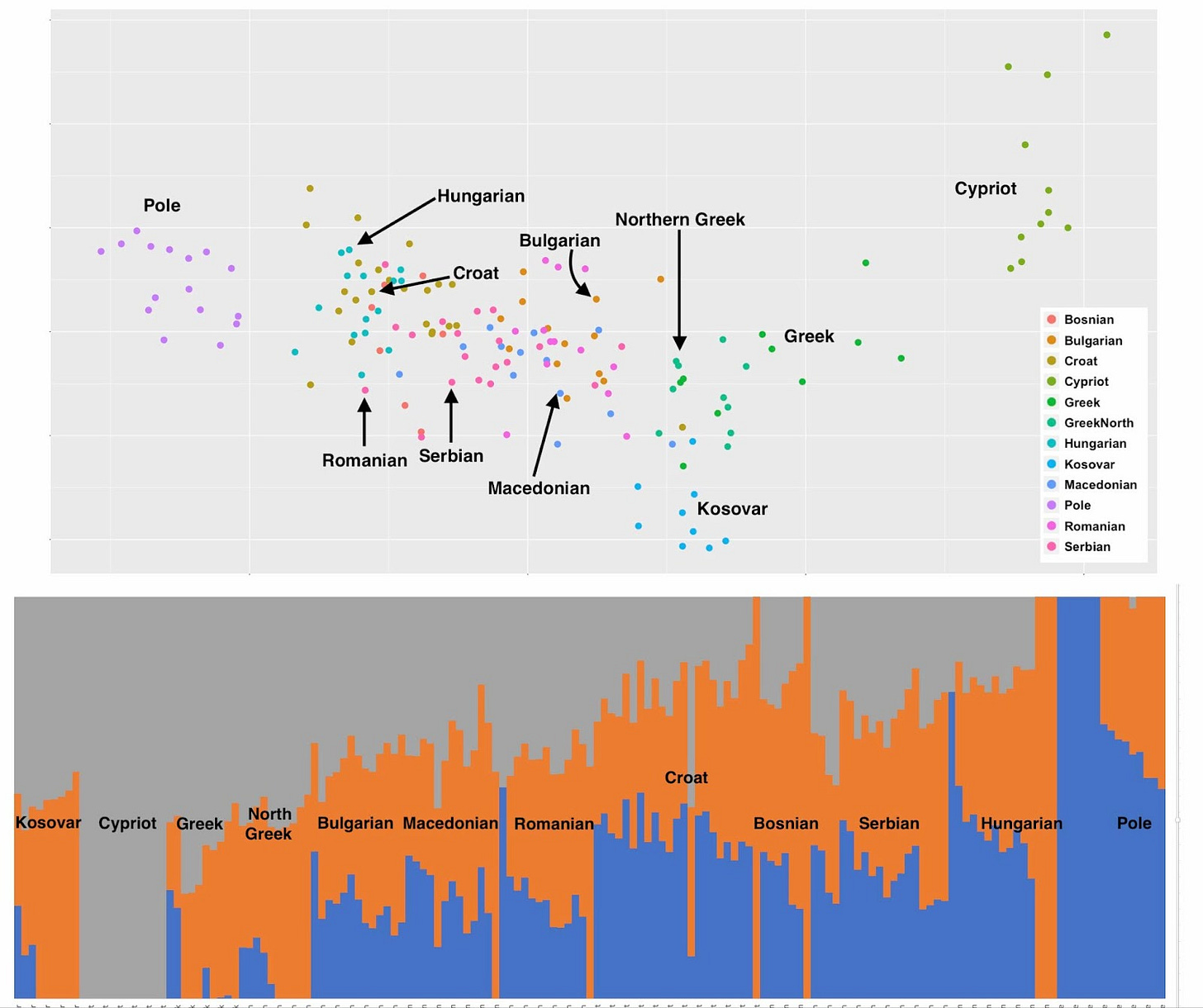

How did it happen that barbarian Slavs, neither heirs to the Imperial Romans nor rulers of the lands they inhabited, were the last people standing as the ancient world faded and the medieval order emerged? One possible model is that of the Magyars, the Turks’ Ugric cousins who left very little genetic imprint upon modern Hungarians, but imposed their identity and language upon the German, Latin and Slavic people they ruled. The Anglo-Saxons present a different scenario: substantial migration combined with a genetic fusion between the invading Germans and native Britons. Though most English ancestry still derives from Britain’s Celtic natives, they left almost no cultural imprint upon their pagan German successors. Missionaries from Rome and Ireland converted the Anglo-Saxons only after they’d descended into a state of total ignorance of their ancestors’ British Christian past. A final possible model when peoples clash would be North America’s settlement, where Anglos arrived in large numbers (African slaves with them), replacing the culture and genes of the native peoples en masse and in totality.