RKUL Hit List 2023: Steppe 1.0, Going Nomad

Revisiting favorite Substack pieces, with research-based revisions

The main project of this Substack is writing the first drafts of newly genetics-informed human population histories. Over the past two decades, genomics has been deluged with manifold riches on an absolutely staggering scale. Computational power, DNA extraction scale (especially from ancient samples) and widespread affordable consumer testing have all gone from intangible pipe dreams to tearing through phases of literally exponential growth. Our powers have risen multiple orders of magnitude in the last 20 years. I have been an excitable front-row commentator on the genomic revolution from the perch of my original blog for two decades now, but this new project of systematically covering what we thought we knew of human history and population movements versus what genomics can confirm or rule out is only a little over three years old for me.

The first full year I published this newsletter, 2021, I began diving into reflections on some of my top favorite historic and prehistoric human populations. People were paying me to write about my favorite stories; I went straight for my own canon of greatest hits first. But I had no idea whether this mailing list would keep growing and most of you weren’t here yet. These are some of the richest human stories I know and only a select few insiders were reading those first drafts. An exciting thing about writing up papers in human population genetics as they’re released… is that as spot-on as they might prove, they’re rarely the last word. Exciting or plot-twisting addenda and further details are always likely to appear around the bend.

So, as the third full calendar year of this Substack draws to a close, I’m revisiting three of my favorite past posts, updating the text to reflect the assorted subsequent findings I’d include if I were first writing those drafts today. First up, a piece I loved about one of my ultimate fixations: the Yamnaya, the steppe people who brought the world Indo-European languages and so much more of who we are genetically and what we are culturally as a species today. Substack had yet to release the preview option for free subscribers when I wrote this piece. So just 907 of you received this paid piece originally. Today, it goes out to some 39,000 total free and paid subscribers.

For all who have already read it, today’s updates appear in bold so you can easily scroll between them.

Before Rome was even a city, up until the age of the gun, the heart of Asia was ruled by nomads. These lords of the steppe struck terror in the hearts of men for thousands of years, and their conquests and defeats shaped the rise and fall of empires.

This is the story of those first nomads, the early Indo-Europeans.

They herded, they rode and they routed

Today 3.5 billion humans speak Indo-European languages, which dominate Eurasia from Spain to the Indian subcontinent. This is the legacy of the pastoralists who roamed the Pontic steppe north of the Black sea 5,000 years ago. They were the original Indo-Europeans. They pioneered the nomadic lifestyle, leaving behind hard toil at the plow and thankless foraging in cold Siberian forests. They chose instead to wander the open grasslands in search of fresh pastures for their herds of sheep, horse and cattle. They were the first to unleash young warriors raised as roving nomads upon the world, predatory packs marching the breadth of a continent in two centuries. We don’t know what they called themselves. We don’t know the names of those who led them. But their cultural innovations and the choices they made transformed our world and made us who we are today. These nameless people left no monuments or seminal texts. Instead, we live with their language, their gods and their genes.

These early Indo-Europeans did not rush into virgin lands. They first bowled over others who were similarly textless. So we have no written testimony of this scarcely human phenomenon steamrolling the settlements of stolid farmers whose ancestors had tilled the land for millennia. The nomads’ inexorable progress onward, onward, outward in concentric arcs, mowing down or swallowing up all who stood in their way, was marked by neither enduring architectural monuments nor ambitious infrastructure projects like Rome left those they subjugated. They came, they took, they surely slaughtered, and they clearly fathered. But with neither written words, nor enduring walls, how do we know them?

Like a black hole, they warped even the distant future of every adjacent nation they touched. And so, like astrophysicists studying a black hole, we grope our way to a picture of the prehistoric Indo-European nomads, not directly, but through the vast arc of Eurasian geography that curls around the windswept steppe to its west, south and east. These barbarian, nomadic Indo-Europeans gave rise to civilized, urban Indo-European societies as far apart as Italy, Anatolia, Iran, and India. The history, culture, mythology and linguistic patrimony of most of Eurasia, particularly its most dominant empires, bear unmistakable if begrudging testimony to violent brushes with the nomad peoples of the steppe. We must only be patient and creative enough to tease out these common threads, field by complementary field. Threads which in the end bind us all. Millennia later, we still bear the scars the invaders left on our ancestors, share their age-old obsessions and journey on their conveyances.

The nomads picked fights they thought they could win. The only way to survive a conquering force as relentless as the steppe raiders was to emulate it, as fully and as quickly as possible. Steppe genes were forced on our foremothers. And in a rushed bid for survival, the societies which resisted and eventually flourished in the face of nomadic predations absorbed as many superior steppe innovations as they could, both the tools and the cultural baggage. If you can’t beat them, you could do worse than to selectively join them. The medieval knight and the Manchu cavalry are but warped refractions of the roving Hun, who found their predecessors on the prehistoric Pontic steppe.

Today, we can trace back those shared threads in myths, mores and mother tongues that span most of the breadth of Eurasia. Archaeology brings us a wealth of circumstantial source materials to interrogate. And the past two decades have been delivering an ever greater granularity of detail in the DNA record of modern humanity’s near-universal steppe ancestry.

In my first steppe post, I dug into the personal “why” of the steppe for me as a long-standing obsession. Now, I delve into what we can surmise or determine about the epochal force that burst out of the steppe 5,000 years ago. Given that this profoundly impactful band of humans made its mark without a single sympathetic contemporary chronicler, this look at the prehistoric steppe people is in large part about the painstaking “how” of reconstructing their unrecorded impact.

Call me by your name

Linguists call the nomads of the Pontic steppe Proto-Indo-Europeans because their language begat those that came later. Archaeologists call them the Pit Grave culture for their practice of burying honored dead in deep pits. Anthropologists once called them Kurgan people for the monumental mounds or kurgans they heaped over the graves of their elites. Kurgans loom over the featureless steppe, hillocks rising a few to dozens of meters above the plains, mute witnesses to legends no one recalls. Today scholars in the West tend to refer to the builders of the kurgans as the "Yamnaya" or “Yamna,” and though the unplaceable word might tempt you to think we're respectfully calling them by their name, it's just a borrowed Russian term connoting something "related to pits." The Proto-Indo-Europeans are an abstraction inferred from later languages, the Yamnaya are concrete (though some have reconstructed the original endonym as *h₂er(y)ós, the prototype for later arya). We know them definitively by their material remains.

Four legs good, four walls bad

The Yamnaya flourished between 3300 BC and 2600 BC in the vast 1,500-kilometer span of steppe between the Dnieper River in central Ukraine and the Ural River in northwest Kazakhstan. Their ancestors had farmed the deep river valleys that gouge the steppe from north to south. Thousands of years later, the Soviet Union would transform this same black soil into the Ukrainian breadbasket, and today, since Russia’s 2022 invasion, the region is the scene of the largest land battles since the end of World War II. While the forests north of the steppe were home to foragers who relied on hunting and gathering as humans had for the whole pre-Neolithic history of our species, the ancestors of the Yamnaya had adopted agriculture and settled down, cultivating grain and raising cattle, sheep, goats and pigs. In this way, they were no different from their contemporaries in Europe and the Near East.

But something changed in the centuries before 3000 BC. The Yamnaya decamped from their farms, with permanent settlements entirely disappearing in the eastern half of their range. We now know that the Yamnaya were the very first farmers in history to entirely abandon agriculture in favor of pastoralism. Rather than fields of golden wheat, their wealth was now denominated in head of cattle, goats, horses and sheep. Especially sheep, a source of meat and milk for subsistence, but also wool they could trade far and wide. The former farmers burst out of the confines of their river valleys, and began to brave the cold dry open steppe, driving their animals before them in vast herds. They had gone nomad.

Pure pastoralism opened human societies up to new possibilities. It is commonly asserted that before the modern era, humans had narrow horizons. They were born, lived and died within a ten-mile radius of their home (today the typical American lives 18 miles from their mother). This was the world of the village. But the Yamnaya left it behind for the plains, an expanse bounded only by the vast sky and the endless horizon. Within a few generations, descendants of the villagers who became the first nomads had driven their herds all the way to the Danube in Hungary in the west, and Mongolia’s Altai in the east, settling at the farthest limits of pastureland rich enough for their animals. Their ancestors had lived hemmed in by valleys less than ten miles wide. Now they traversed the whole length of Eurasia in search of grazing land and opportunities. The magnitude and ease of migration were such that geneticists have found men buried in Eastern Europe 5,000 years ago who were contemporaries and first cousins to others found in Mongolia. More kin, as close as second cousins, have since been detected in the ancient DNA record, scattered at great remove from one another, all across the Eurasian steppe, underscoring that these generations were truly ricocheting in every direction.

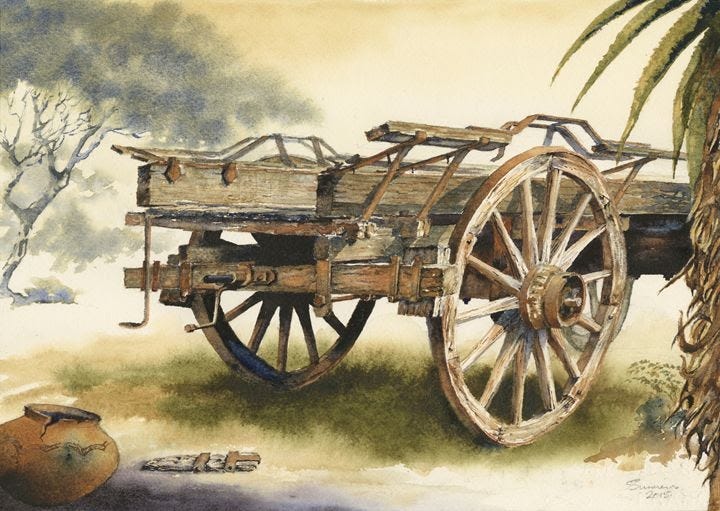

Of course, humans had raised animals since the beginning of agriculture. But with the Yamnaya, the animals became everything, a one-stop source for sustenance, clothing and transport. The Yamnaya pioneered simple but effective carts drawn by oxen, allowing their animals to lug their possessions across the steppe. This transient lifestyle established the template which persists down to the present in Mongolia and Kazakhstan. Yamnaya migrations were reflected in telltale disturbances they left across the landscape. Soon kurgan mounds begin to appear further west into Europe, with many of them dating to just after 3000 BC, tangible traces of an inexorable grassland tide pouring into the forests beyond the steppe’s western cusp.

All at once

Archaeologists and linguists have long debated whether the kurgan builders moved westward in a mass migration, or whether their culture diffused through imitation. In 2015, geneticists answered the question definitively: the Yamnaya had migrated in a vast swarm. Comparing DNA from remains in the pit graves to ancient and modern individuals, they found the majority of Northern European ancestry comes from the Yamnaya. The nomadic migration was not one of elite bands, it was a nation on the move, a total genetic and cultural transformation of a continent. The Yamnaya contributed the lion’s share of ancestry to the Corded Ware, a late Neolithic culture on the North European plain, so-called for its pottery style. Geneticists have discovered Yamnaya men buried in kurgans who were the recent ancestors of men in Corded Ware burials. The Corded Ware were in fact just Yamnaya who adopted a novel pottery style as they penetrated into the forests north and west of the steppe.

The latest findings in 2023 makes it clear that the Corded Ware people were often genetic cousins of the Yamnaya, no more than 4-8 generations removed. And yet about 25% of their ancestry mix was novel, most of it owing to foremothers from the last Neolithic culture of Poland, the Globular Amphorae. The Yamnaya-Globular Amphorae synthesis gave rise to a mixed agro-pastoralism that would swiftly wash outward everywhere from the shores of the Atlantic to Bay of Bengal. This underscores Yamnaya flexibility, as they adapted themselves to an ecology very different from the steppe they’d mastered.