From Formosa to the Four Corners of the Earth: the Austronesian expansion’s long arc

Epic Explorers of the Stone Age: the full scope of Austronesian audacity, part 2/2

What follows concludes a two-part exploration (read part 1) into what genomics and ancient DNA allow us to confirm about the Austronesian people’s millennia of audacious voyages. Already know your Austronesians? Before we continue, feel free to test the state of your knowledge with this quiz!

In the 1600s, Taiwan, then known as Formosa and under Dutch control, was regarded as a barbarian frontier province, nigh unto empty by Han standards, and used as an escape valve for mounting mainland Chinese population pressure. By the 1700s, this unchecked inflow of mostly Fujianese immigrants had tipped the island’s demographic majority over to the Han. This Han ascendance would have unwelcome sequelae both for the short–sighted Dutch colonists who once welcomed the unchecked flow of peasant immigration and for the ethnically Manchu Qing dynasty, wary of yet another Han-dominated province of China. But for our ancient Austronesian story, this recent chapter of Sinicization and intensive settlement is merely a layer to be peeled back. Who were the native Taiwanese people being progressively demographically overwhelmed by that Han tsunami?

Throughout those centuries of Dutch, Tungning and Qing rule, native Taiwanese had continued ranging across most of the island, hunting and farming as they had for millennia. The Chinese economic relationship with the native Taiwanese resembled that then developing in North America between Europeans and Native Americans, with the indigenous inhabitants trading the newly arrived settlers products like deer skins for imported finished goods.

Today 600,000 people of indigenous Taiwanese ancestry remain on the island, maintaining their cultural traditions in eastern-highland strongholds. Sixteen indigenous Taiwanese tribes are officially recognized, including both the Ami and Atayal, who appear among the Human Genome Diversity Project (HGDP) sample populations. They are divided between those of the highlands in the east that occupy two-thirds of the island, and those of the western plains, where most of the population resides, and who are more Sinicized. While the Han speak a Sino-Tibetan language, the native languages of the indigenous Taiwanese are all Austronesian. In fact, of the 14 subgroups of Austronesian languages around the world, 13 appear on Taiwan alone. Though a minority faction of scholars challenge this taxonomy, linguistic analyses of Austronesian languages using best-of-breed phylogenetic methods do seem to concur on Taiwan being basal.

The standard explanation for these sorts of patterns in human evolutionary genetics, where a lone narrow geographic region harbors the lion’s share of existing diversity, is that this busiest, most diverse node usually marks the origination point of a broader population movement. Africa is the most genetically diverse continent, and it is also likely to have harbored the modern human lineage the longest. Likewise West Asia alone boasts more genetic diversity than the rest of the vast Eurasian super continent. And East Asia is genetically more diverse than the New World. As populations branch out, those fateful pioneers whose genes are an arbitrary subsampling of the initial population, inevitably grow more and more homogenized, constrained to only ever draw on a subset of the original population’s heritable variety, progressively cutting into their patrimony of initial diversity over time. The same dynamic applies to cultural traits like language. Given Taiwan’s motherlode of linguistic diversity, we can confidently conclude that this must be where the Austronesian languages began their expansion millennia ago, with a fateful subset of that day’s population spreading southward, before branching west and east into Malayan and Polynesian subgroups.

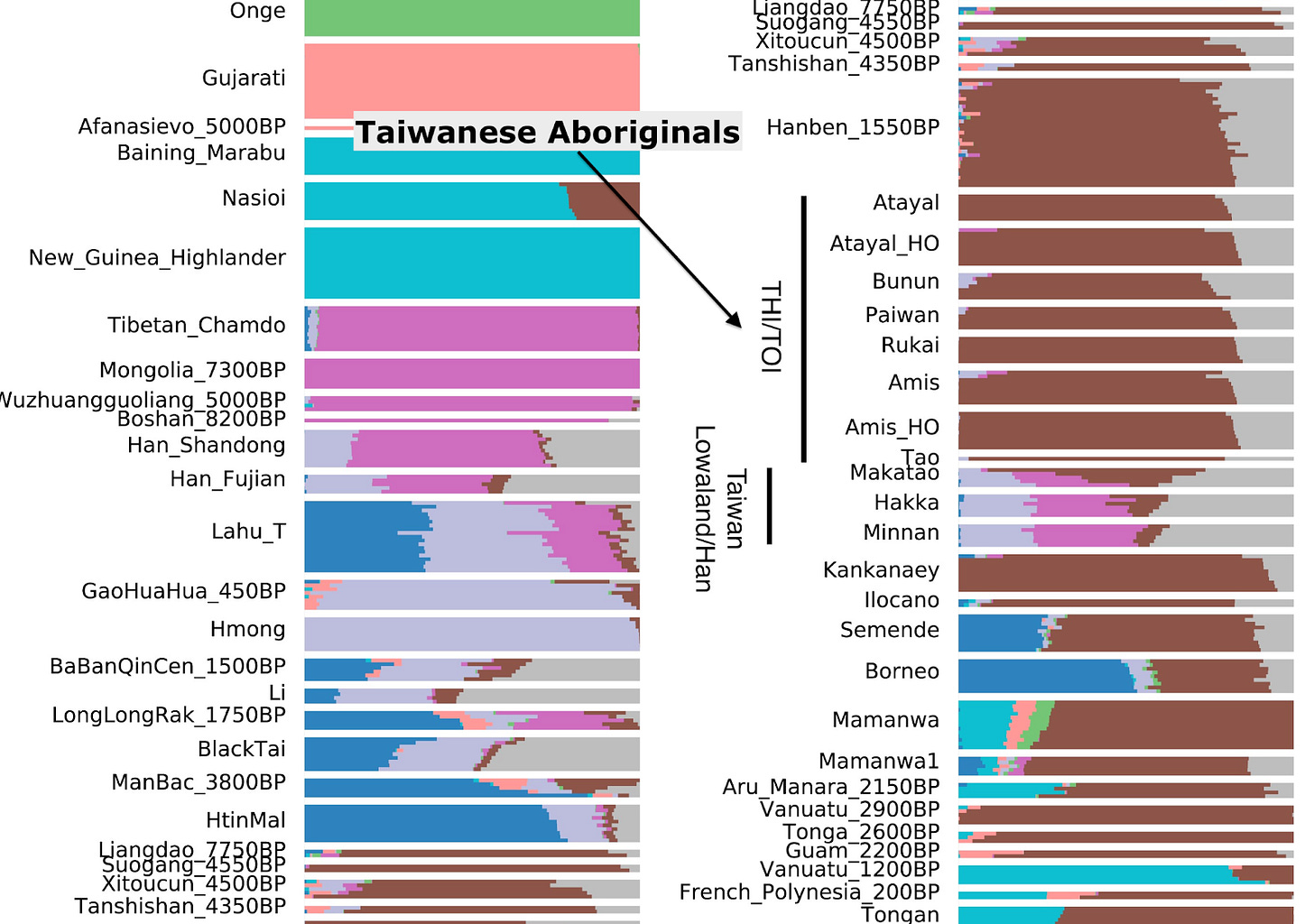

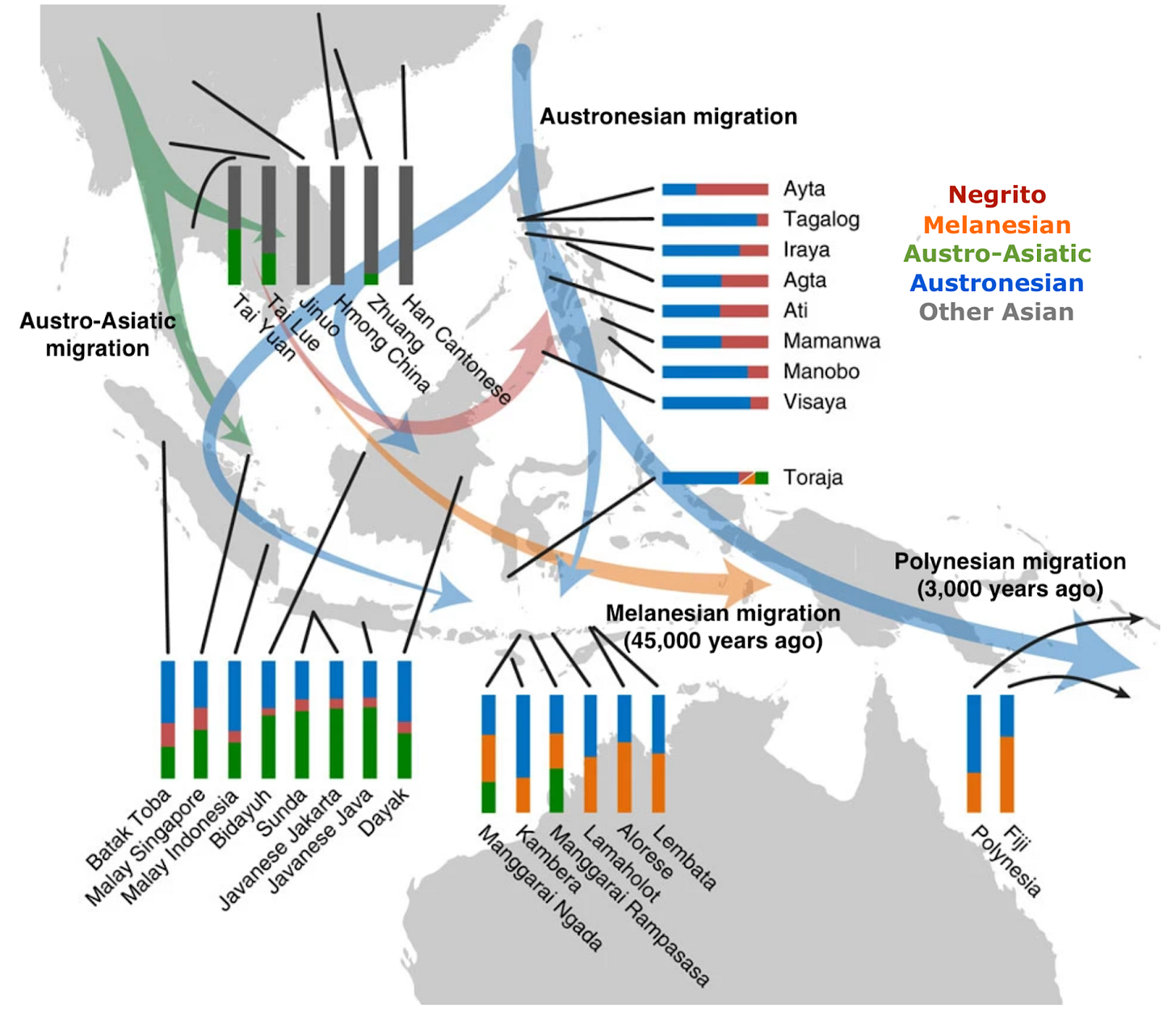

Though those two Taiwanese aboriginal groups, the Atayal from the north and the Ami from the south, have long figured in human population-genetic studies because they contributed to the HGDP dataset begun in the 1990s, a 2023 paper examined a wider range of Taiwanese tribes to characterize the dynamics of a possible “out of Taiwan” expansion. A simple admixture-based analysis pooling world populations, both modern and ancient, and allowing ancestral clusters to fall out of the data, shows that the dark-brown element predominates in Austronesian speakers, is maximized in the Kankanaey ethnic group from Luzon in the Philippines, and appears ubiquitous in indigenous Taiwanese. Samples from Borneo and southern Sumatra (Semende) in Indonesia show this component as well, but always paired with the dark-blue element that predominates in the Htin ethnicity of Thailand and Laos. The Htin speak an Austro-Asiatic language, and descend from the first wave of rice farmers to arrive in Southeast Asia. This Austro-Asiatic component also appears in a high fraction in neolithic Man Bac samples from northern Vietnam dating to 1800 BC, which correlates perfectly with agriculture’s arrival in the region from the north. In maritime Southeast Asia, it seems clear then that intrusive Austronesian populations mixed with earlier Austro-Asiatic populations.

In contrast, the Tongans, selected here for the purpose of representing modern Polynesians, show a high fraction of the Austronesian ancestral element, but without a substrate of Austro-Asiatic ancestry. Instead, what is evident in these populations is a minority contribution closely related to the Melanesian ancestry of New Guinea highlanders. While the branch of Austronesian voyagers that moved west encountered Austro-Asiatic speakers farming rice in Borneo, Java and Sumatra, those that tacked east encountered Melanesian populations. These contacts are faithfully reflected in their contemporary genetics.

The earliest ancestors of the Polynesians are almost certainly what is known in the archaeological record as the Lapita culture, which spread across Melanesia and western Polynesia between 1500 and 1000 BC, originating from a forward Austronesian hub in the northern Philippines (the first stop out of Taiwan). The ancient DNA from the earliest sites (in Tonga) is notable in showing almost no Melanesian ancestry, suggesting a later admixture event swept across Polynesia. Genetically, the closest modern populations to the Lapita seem to be ethnicities in northern Luzon and indigenous Taiwanese, confirming a north-to-south migration event after 2000 BC (also traceable in the archaeological record).

The Lapita’s Polynesian descendants became famous as the world’s most audacious open-ocean mariners, but their overall cultural package shows evidence perhaps more than anything of their ancestral Austronesian adaptability. Rice agriculture arrived in Taiwan 5,000 years ago, likely as part of the cultural package of the proto-Austronesians, who migrated from the Chinese mainland. Rice and Austronesian culture are closely linked on their southwestern migration, one of their legacies being to have brought a more intensive wet-paddy rice agricultural system to regions that had been previously opened to agriculture by Austro-Asiatic farmers (eventually carrying this package even to Africa, to the Madagascan highlands). But as another contingent of Austronesian mariners sailed southeast from the Philippines, this subgroup seems to have abandoned rice, in favor of crops like taro, yams and banana. The word for rice even disappears in the proto-Polynesian language, around 1000 BC. Why? Rice seeds do not survive well in salty conditions, a common characteristic across islands where much of the land is very near to the ocean. Rice is also ill-suited to the thin soils of many Pacific islands and atolls, providing a poor return on intensive cultivation. What had been essential, western Austronesians’ very staff of life, was quickly jettisoned by pragmatic eastern Austronesians.

Paleogeneticist David Reich has said that one of the major insights of ancient DNA is that markers tracing lines of biological descent can just as well be tracer dye for cultural movements. The Austronesian languages, from Taiwan to Madagascar to Easter Island, are all clearly interrelated. But with ancient and modern DNA, it also grows abundantly clear that their speakers share a common genetic heritage, overlaid at various depths upon the local substrates with which they synthesized. Using ancient DNA samples from northern and southern China dating to the period between the Last Glacial Maximum 20,000 years ago and the end of the last Ice Age 11,500 years ago, researchers have shown that the genetic elements that coalesced in Taiwan by 5,000 years ago seem to have antecedents in local foragers who ranged across the coastlands of southeast China when sea levels were lower and East Asian populations were separated into very distinct northern and southern clusters.