RKUL: Time Well Spent 03/03/2024

Super Grandma edition

For the first time ever, parents going through IVF can use whole genome sequencing to screen their embryos for hundreds of conditions. Harness the power of genetics to keep your family safe, with Orchid. Check them out at orchidhealth.com.

Your time is finite. Your phone and the internet stand ready to help you squander it. Here are my latest picks for spending it well instead. Feel free to add more in the comments.

Books, what else?

I’m number three. And I have a blunt kid happy to tell me so. First is mama, of course. And then is (maternal) grandma, and if I really insist on counting that deep, finally me.

Today my kids’ grandma turns 80. 03/03/44. It’s a pretty great date of birth. My kids are all her grandkids. And as far as they are concerned she is kind of all their grandparents. Yes, they are spoiled to have four living grandparents who love them. But when told to list their nuclear family in school exercises, it is only Grandma they ever ask to be allowed to pencil in, even though they know she’s not the generations their teacher means.

By coincidence, their maternal grandmother is the sweepstakes winner of getting her genetic contributions into our kids. She is proud to share some 28% of my kids’ aggregate genetic material, whereas their grandpas kicked in roughly 22% and 26%, and my mom 24%. But she’s in the first generation of human grandparents who could ever have actually known such statistical arcana, going beyond the tidy 25% expectation Mendel’s laws give you. And like all her millennia of less genetically informed forebears, I don’t have to tell you that she couldn’t possibly care less what percent they are her. What matters is that they are hers to dote on and help shepherd.

Psychology and genetics are 75 years into systematically examining the measurable impact the longevity and presence specifically of maternal grandmothers have on offspring outcomes. In 1952, Nobel-prize winning biologist Peter Medawar developed the hypothesis that grandparents might have significant fitness impacts on their grandchildren. Over the subsequent decades, the evidence began accumulating that the maternal grandmother’s presence in particular is correlated with higher survivorship among her grandchildren. This observation led to a follow-on hypothesis that menopause, which sunsets female reproduction, emerged as an adaptation to shift a woman’s focus away from having more of her own children, so she could instead invest in her grandchildren’s well-being, and in particular, her daughters’ children.

So happy birthday, S. I admit it, you’re number two! And my precious genes couldn’t be luckier.

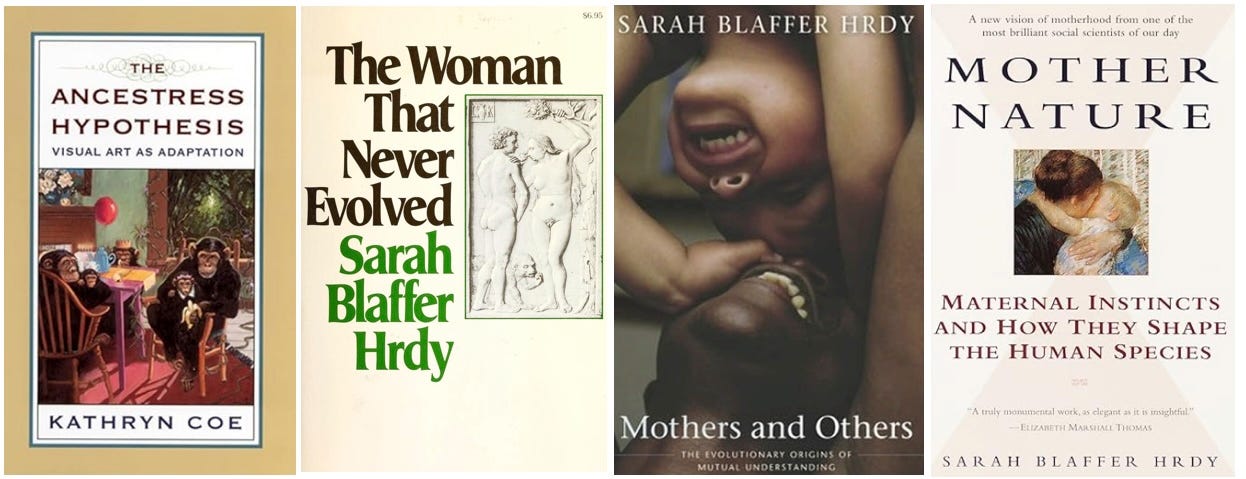

Sarah Blaffer Hrdy is a primatologist and evolutionary biologist who has made major contributions to sociobiology and evolutionary psychology. She has written three books that explore the topic of female primates and how their behavior and preferences have shaped our evolution: 1981’s The Woman That Never Evolved, 1999’s Mother Nature: Maternal Instincts and How They Shape the Human Species and 2009’s Mothers and Others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Hrdy did her Ph.D. at Harvard on infanticide in langur monkeys under anthropologist Irven DeVore, with further supervision from evolutionary biologists Robert Trivers and E. O. Wilson. There, she had firsthand experience with the debates that broke out during sociobiology’s early years and crested after Wilson’s 1975 book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (Hrdy makes an appearance in Ullica Segerstrale’s Defenders of the Truth: The Battle for Science in the Sociobiology Debate and Beyond; and unlike many 1970’s sociobiologists seem Hrdy was definitely ambivalent about the field’s 1980’s rebranding as evolutionary psychology, possibly due to her background in animal behavior as opposed to human psychology).

The Woman That Never Evolved, Mother Nature and 2009’s Mothers and Others all operate within the scholarly tradition that emerged in the 1970’s as sociobiology and evolved in the 1980’s and 1990’s into evolutionary psychology and behavioral ecology. Nevertheless, Hrdy does not hesitate to admit in these works that her perspective as a woman and a mother allow her to access insights and relevant dynamics that might be less obvious or even hidden from her male colleagues. In Mother Nature Hrdy recounts some obtuse comments from Trivers in particular which she felt inaccurately removed agency from female primates. Hrdy’s research on infanticide and mating strategies highlighted the role of female agency in primate societies, and ultimately, human evolution.

Before shifting to humans in the later books, 1981’s The Woman That Never Evolved puts the focus on primatology, showing how clever, resourceful and machiavellian primate mothers can be, going far beyond the stereotype of behaviorally simple nurturers with a singular instinctual drive. Drawing on her own research during her Ph.D. in the 1970s, Hrdy argues that female primate sexuality evolved to reduce the risk of infanticide from males. This sometimes took surprising forms; females sometimes seem to maximize the prospect of male support for infants by leaving paternity within the troop uncertain, so that a single certain father is replaced by many potential fathers. This model anticipates research from anthropologists who describe the idea of “partible paternity” in some tribal societies, where males act benevolently toward children who might be their own, as opposed to acting with full certainty. The Woman That Never Evolved is to a great extent a working out of the sort of logic at the heart of her mentor Trivers’ work in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, which took individuals and attempted to understand their optimal strategies in a game-theoretic context. Rather than being appendages to dominant males, females in many primate societies form multigenerational units that provide true stability for the troop.

In 1999’s Mother Nature Hrdy shifts her focus more narrowly to human maternal instincts and the mother-child dyad. Again, she dispenses with any simplistic notion that female humans are one-dimensional nurturers, operated upon by the inevitable forces of evolution, examining them instead as active agents who balance a host of aims and goals beyond that of being an empathetic mother. Primate mothers, and human mothers above all, not only protect their children, but go on supporting them in adulthood. The flexibility of human nature and the varied strategies of mothers are underscored by the wide variance in social and cultural attitudes to natalism, from foraging societies that practice birth spacing and keep their numbers in check through extended weaning, to agricultural societies where elite women are encouraged to maximize the number of children. Mother Nature explores the paradox that human females have a particular set of hard-wired instinctions, but they express themselves in such a multiplicity of ways that their behavior is highly context-dependent, from matriarchs operating behind a literal veil to CEOs who are publicly “leaning in.”

Mothers and Others shifts the focus beyond the mother-child dyad, and highlights the role of cooperation within the tribe and ubiquitous alloparenting (child raising and care by anyone besides biological parents) in bringing up the next generation. Hrdy believes that alloparenting, the outcome and perhaps driver of our cooperativeness, marks a major difference between ourselves and our nearest ape relatives, and explains how we can scale our societies so well and why our childhoods are so long. In most traditional human societies, children are variously raised by siblings, cousins, uncles, aunts and yes, grandparents. Groups of females in particular serve as the social core of many ape and human societies, passing down knowledge and wisdom through the generations in a culture where males may suffer high mortality rates. Yet the 20th-century emphasis on a nuclear family in the US is in many ways historically atypical, and switches our child-rearing model more toward the one typical among our chimpanzee cousins, with greater isolation and focus upon the mother and child alone. Mothers and Others argues that alloparenting is a major variable in the development of human societies, allowing for both specialization across a culture. Not only does alloparenting reduce the risks to children of dependence upon a single parent, it also allows younger members of a group to learn from many different adults who may have a range of skills and insights to transmit. Modern American prosperity allowed for the autonomy of the nuclear family where the mother could be a full-time homemaker, but that economic productivity is ultimately rooted in advances in human culture that grew out of a primate society where offspring were raised in a multigenerational and communal context.

Kathryn Coe’s The Ancestress Hypothesis: Visual Art as Adaptation presents a theory for the origins of one of the major ubiquitous elements of human culture, symbolic representation. She suggests that visual art, from body art and funeral ornamentation to painting, was primarily cultivated by women and promoted social relationships and cooperation among relatives and descendants of a common ancestor. This links art to kinship and ancestry, as opposed to creative mate-attracting functions. Coe’s argument for the origin of art contrasts with its role in ancient Greece and the Renaissance, where it was seen as a competitive endeavor between males to signal to potential mates. Human cooperation and social cohesion emerges out of the creativity of female lineages, bound together horizontally across a generation and vertically across many generations by visual markers of identity.

Though Peter Medawar may have introduced the idea of grandparents being critical in influencing the fitness of grandchildren, it was anthropologists like Kristen Hawkes in 2004’s The grandmother effect that looked at the theoretical underpinnings and empirical evidence of the phenomenon. The evolutionary relevance of grandmothers seems to kick in after children are weaned, and is accentuated when grandmothers live in the same village as their grandchildren. In other words, it is likely the grandmother’s role in alloparenting that is mediating their impact on their descendants’ fitness. Hawkes and her colleagues argue that the essential role of grandmothers explains the evolution of the physiological cascade that leads to menopause, curtailing a woman’s reproductive capacity decades before her death. In short, the fitness outcome of reducing the mortality of their descendants is greater than a longer conception window and late-in-life child-rearing. Other researchers have even done recent work that illustrates the same phenomenon of menopause among four whale species that are notably matrilineal and matriarchal in their social organization.

When it comes to humans, over the last few decades Finnish evolutionary biologist Virpi Lumma has accumulated a large body of evidence for the importance of maternal grandmothers in particular by mining the centuries of detailed Finnish Lutheran church records of births, marriages and deaths. Going back to Hrdy’s thesis about the importance of alloparenting, though the birth-mother may be the primary caregiver, the individuals they rely on for aid in child-rearing are disproportionately likely to be their sisters and their own mothers, as opposed to their male partner’s kin. Additionally, evolutionary psychologists have pointed out that because maternity is dead certain while paternity is probable, women are more sure in most societies of their biological relationship to their daughter’s children than to their son’s. In this way, the empirical patterns observed by Lumma have a theoretical rationale over the longer evolutionary scale. In the domain of anthropology, the importance of the maternal lineage crops up in counter-cultural universals in even patriarchal societies; for example, the importance of maternal uncles in ancient and medieval Greek history and modern Indian culture, has long been noted despite the clear patriarchal and patrilineal character of these societies.

Thought

The Invisible $1.52 Trillion Problem: Clunky Old Software - Old code piles up and raises the risk of hacks and other breaches, even on new devices. Our compounding ‘technical debt.’ The US economy is 28 trillion dollars, so tech debt is a major drag on our productivity. When code gets antiquated and elaborated enough it’s inevitable that mysterious bugs and breaks will occur that will crash systems.

America’s Oil Power Might Be Near Its Peak - The production growth that blunted surging oil prices is dwindling. A lot of this prediction is predicated on the increase being due to extraction in Texas’ Permian basin, and the Permian wells getting tapped out. But I want to note that local governments have banned offshore drilling on the west and east coasts, so there are likely reserves we haven’t tapped, and might tap in a world of genuine oil scarcity and high prices.

Can AI Unlock the Secrets of the Ancient World? If this pans out this might be bigger than ancient DNA in becoming a tool to understand the human past. Automation and AI will probably result in a rapid expansion of our textual database of the ancient world, from cuneiform to scrolls.

Europe's First Civilization: the Vinča Culture. Dan Davis’s videos on ancient European prehistory are all worth watching, and this particular one highlights Europe’s first complex farming society in the Balkans.

Data

50,000 years of Evolutionary History of India: Insights from ∼2,700 Whole Genome Sequences. The biggest finding of note to me from this paper is that it looks like there were two indigenous Denisovan populations that were assimilated by ancient Indians.

Y chromosome sequencing data suggests dual paths of haplogroup N1a1 into Finland. It seems that there were two paths of migration of Finnic peoples into modern Finland. First, the conventional path from the east through Karelia, and second another route into southwest Finland via Estonia. This aligns with a strain of thought that Sami and Finns entered via separate directions. Second, the R1a lineages in Finland are mostly related to those in Russia and Eastern Europe rather than Sweden, indicating that the Nordic Bronze Age Battle Axe Culture R1a lineages all went extinct after the Finns’ arrival.

100 ancient genomes show repeated population turnovers in Neolithic Denmark. The foragers were replaced by farmers, and the farmers were replaced by steppe pastoralists. These changes were correlated with changes in physical characteristics, diet and land use. The genetic and cultural preconditions for modern Dane ethnicity derive from the period after 3000 BC.

How to validate a Bayesian evolutionary model. Too many researchers use these tools without understanding how they work and how well they work. “Out of the box” so to speak. This preprint outlines best practices to test how well Bayesian methods work in evolutionary biology.

Unifying approaches from statistical genetics and phylogenetics for mapping phenotypes in structured populations. Preprint that shows how many of the use cases in medical population genetics and evolutionary population genetics emerge out of the same framework.

My Two Cents

There’s still no free lunch, free subscribers; my most in-depth pieces for this Substack remain beyond the paywall. I’ve posted two pieces on German genetics recently:

Hans, are we…. the admixed ones?:

After World War II, the German nation officially turned its back on Nazi ideology and all its trappings. German rejection of 20th-century nationalism’s demons precluded any further inquiry into the origins of the German volk. And yet science progresses, just as surely as medicine or technology. At some point, it would be in even the most wary, risk-averse Germans’ interest to consider the reality that human genetics has long since become a modern science that sheds light on human history with almost miraculous depth and precision, and retains no material connection to the dark arts of intuitive pseudo-taxonomy practiced by misguided race scientists 80-100 years ago. German physical anthropology’s early 20th-century susceptibility to politics owed to the reality that it was neither fundamentally scientific nor governed by any of the domain’s built-in checks or ethos of provisionality and humility. It was thus tragically suggestible and easily reshaped to the given moment’s Zeitgeist; a “science” poorly anchored in reality proves easily hijacked for bias-fueled caprices and passing preferences.

Human population genetics’ enduring neglect in Germany is an unfortunate omission that hobbles our understanding of Europe, redacting the dramatic events playing out at center stage of an entire continent. You can read The genetic history of France, Poland, Italy and Scandinavia, but the literature offers nothing comprehensive on Germany, which arguably plays anchor to the vast span of Northern Europe.

Germany stands athwart the European continent, a north-south axis transecting the North European Plain and ascending up into Central Europe’s highlands. From its northernmost regions came the barbarian Germanic tribes of antiquity, all of whose roots date to the Nordic Bronze Age 4,000 years ago. Southern Germany may also have been the Celt urheimat (cradle of the Urnfield and Hallstatt cultures 2,500 to 3,500 years ago), while eastern Germany has witnessed the waxing and waning of Baltic and Slavic peoples over the last few millennia. It was in western Germany 4,600 years ago that the late Corded Ware Indo-Europeans became the Bell Beaker Indo-Europeans, these latter destined to bring much of the continent under their sway. It was the Bell Beakers who brought Indo-European languages to Spain, the British Isles, Italy and France. It was the Bell Beakers whose expansion and diversification would later give rise to the western Indo-Europeans; the Celts, Italian tribes like the Samnites, Umbrians and the Latins, and lastly, to a great extent, the Germans.

The two Indo-European revolutions and Germania’s rise:

Cultural synthesis driving the emergence of the Germanic world should not be surprising; that world sits at the continent’s very heart. It is forever the busy byway, never the terminus. In the first synthesis, the Neolithic LBK culture that brought farming to Northern Europe absorbed Mesolithic foragers (the ruling male elites of later Neolithic societies sported hunter-gatherer Y-chromosomal haplogroup I2). In the second synthesis, nearly 5,000 years ago the Globular Amphora Culture, Eastern Europe’s last Neolithic farmers, were absorbed into the Yamnaya horde, resulting in the Corded Ware people. Then, in turn the third synthesis saw the Battle Axe people, descendants of the Corded Ware, absorb Europe’s last foragers, the Pitted Ware Culture, while at the same time Bell Beaker influences were diffusing northward from Central Europe. Out of this emerged the Nordic Bronze Age, when the cultures of Scandinavia overflowed out of their homeland onto northern Europe’s North and Baltic Sea coasts. As prehistory faded and the light of history dawned over tribes congregating around the Baltic, it was clear they too were magnetically drawn to the south’s powerful economic engines. Soon Germanic-speaking people came to dominate the continent’s center, absorbing the residual Celtic peasantry that remained in the wake of their elite’s flight in search of plunder. In their own turn, the opportunistic Germanic elites would imitate the Celts, evacuating vast swaths of the north to migrate east, like the Goths, or west in the instance of the Vandals, and south in the Lombards’ case. This rearrangement of power during the early medieval period resulted in an influx of Slavic-speakers into the eastern frontier of the German-speaking world, inaugurating the cultural back and forth that has defined the last millennium, from the medieval German Crusades against pagan Slavs in the 13th century down to Poland’s annexation of eastern Prussia.

Discussion

All my podcasts go ungated two weeks after their Substack release. So I encourage subscribers on the free plan who’d like to automatically get them to subscribe to that podcast stream (Apple, Stitcher, and Spotify). If you want to listen on YouTube, please subscribe.

Here are my guests (and monologue topics) since the last Time Well Spent:

ICYMI

Some of you follow me on my newsletter, blog, or Twitter. But my own domain also has all my links and updates: https://www.razib.com

There you’ll find links to the few different podcasts I’ve contributed to or run, my total RSS feed, links to more mainstream or print articles when I remember to post them, my Twitter, the occasional guest appearance, etc.

Over to you

Comments are open to all for this post, so if you have more reading/listening suggestions or tips on who I should be talking to or what you hope I’ll write about this year, lay it on us.

The Finland paper: Shouldn't be an entirely surprising finding to linguists. Basically, the southwestern route is the one of the so-called Baltic Sea Finns whose dialects later branched to modern Finnish, Karelian and Veps. Finns probably started crossing in increasing numbers by roughly 0 AD, but losing the over-sea language connection around 500 AD, with SW dialects showing even later exchange of influences, which you can still hear in some regional accents, and which other Finns may make fun of sometimes. (This extends to how Estonian sounds to many Finns by the way, that is, quite funny, in a cute way of course. Curiously, this doesn't seem to be the case vice versa, generally, although Estonians certainly do make their fun otherwise of the half-naked, half-tamed and half-mannered herds of Finnish "reindeer", poro's, seasonally roaming Tallinn and Pärnu searching for more booze to guzzle and karaoke bars for making their mating sounds.)

The eastern routes probably brought other Western Uralic languages, as well, aside from Proto-Saami (I recall maybe Valter Lang* hypothesizing about one branch closer to the Baltic Sea Finns than the Saami cluster, entering through the Karelian Isthmus), but they must have got swallowed (linguistically speaking at minimum) either first by the huge Saami expansion (the origins of which Ante Aikio places in a very small speaking community in Lakeland Finland or perhaps more eastwards in Karelia, starting to expand some time around during the latter half of the first millennium BC), or the later waves of Finns (and in the east, Karelians and the Veps) slowly settling every corner, starting from the most arable, and finally ending up even in Lapland.

It would seem unlikely that the Finns wouldn't have mixed with the Saami-related people especially inland, or basically integrating them wholesale by culture and language switch. To what extent that happened, and what effect it had on the ancestry of the more eastern Finnish tribes like the Karelians and Savonians, I don't know. The "forest Saami" would have been HGs, mostly, I presume, *maybe* with some crude slash and burn agriculture. So, probably small populations anyway.

From historical times we know that in Lapland at least they were versatile HGs and fur traders, but that lifestyle demanded a lot of territory, and when the Finns settled there with a mode of sustenance more effective per km2, the Saami started to switch to the Finnish lifestyle before running out of territory.

[*] Valter Lang: Homo Fennicus, 2020. Original in Estonian from 2018. Too bad it's not in English. It's a very ambitious synthesis of linguistic, archaeological and also genetic evidence, giving an account of the "arrivals" of those Western Uralic people who would come to be known as the Baltic Sea Finns. It includes interesting discussion on the different "natural" routes to the Finnish peninsula, largely river networks and other waterways, as that's how you moved around there. Nice hand-drawn maps and whatnot.

"‘From Genghis Khan to Tamerlane’ Review: Empire on the Steppe While slaughtering and enslaving entire populations, the Mongols could be meticulously tolerant and impartial about religion." By Melik Kaylan | March 4, 2024

https://www.wsj.com/arts-culture/books/from-genghis-khan-to-tamerlane-review-empire-on-the-steppe-6751d648

"For sheer information, Mr. Jackson’s book is incomparable. We learn that Timur loved to gather intelligence about his rivals. He revived a courier system of relay horses that “enabled news to be transmitted extremely rapidly.” He planted spies throughout enemy territory, including “merchants, craftsmen, physicians” but also “vicious wrestlers and dissolute acrobats” as well as “charming water-carriers and genial cobblers.” He also deployed “deliberate disinformation,” acquiring a “reputation for guile.” We learn about the weaponry of the time, about elephants with swords attached to their tusks and flaming-oil throwers. During one short campaign, Timur’s army expropriated millions of sheep and hundreds of thousands of horses, camels and oxen. The spoils of war were a big reason why Timur’s men followed him loyally. ...

The book teems with insights. Across 700-plus pages, Mr. Jackson has produced an authoritative work of uncompromising erudition, likely to be a definitive study of the subject for many years to come."