The two Indo-European revolutions and Germania’s rise

From small-scale farmers to the rulers of the post-Roman world

Related: Hans, are we…. the admixed ones?.

Because we lack writing before the Iron Age in Germany (and even then the writing is by the Romans), archaeology and genetics are our sole sources for a narrative of the pre-Roman peoples’ rise and fall. But it is clear that after the initial circa 2800 BC arrival of the Corded Ware-derived Single Grave Indo-Europeans to Central Europe, cultures did shift repeatedly, as signaled by successive trends in pottery and other artifacts, and with these, who dominated within these societies. We now know that Bronze Age Europe was defined by patriarchies; men ruled. And here we have more than DNA and archaeology to go on. Tacitus, 2,000 years ago, records that German inheritance patterns were patrilineal, and it is likely this practice dated to long prior with the arrival of the steppe warriors.

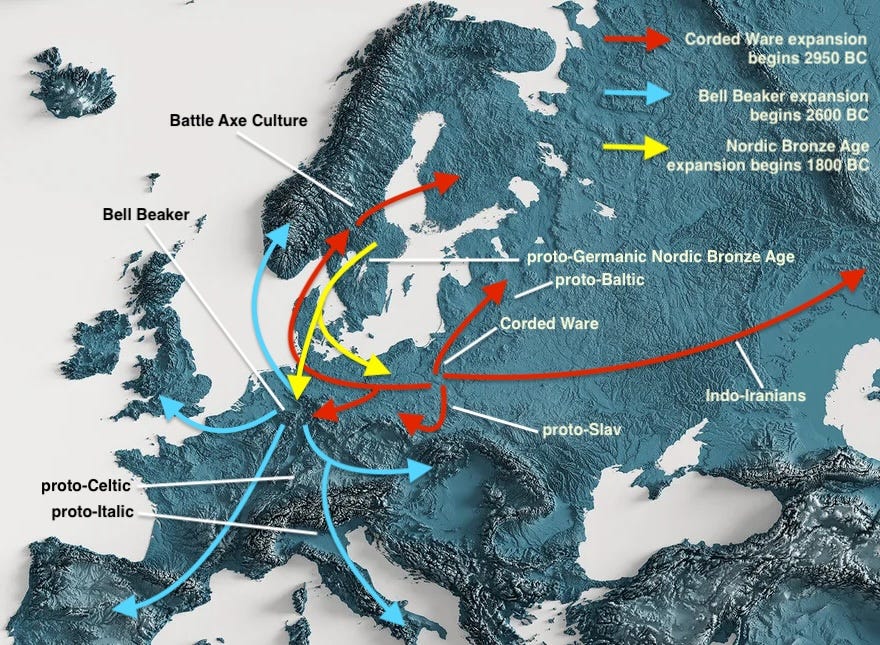

But the ascendancy of the Single Grave people in Central Europe was short-lived. Around 2600 BC, a new artifact, the bell beaker, joined the Rhine River valley archeological patrimony from the west, a final cultural innovation of Neolithic Europe in Iberia that dispersed briskly along the Atlantic facade and up along the rivers of France. In the centuries prior to the arrival of the bell beaker technology In western Germany, the early Single Grave culture seems to have mixed further with local farmers. The general proportion of steppe ancestry had declined below 70% by the time the beaker tradition arrived, as remnant Neolithic communities were absorbed into the steppe-derived cultures.

Within a century, another wave of Indo-Europeans defined by this new style of pottery, the Beaker people, exploded out of western Germany in all directions. In 2500 BC, they arrived in Britain, replacing the Neolithic societies and genetically overwhelming them with such totality that within a few centuries, 90% of remaining ancestry was that of the Beaker people, not that of Stonehenge’s Neolithic builders. The same dynamic occurred in Ireland, as farming-societies known for their monumental architecture gave way to a more pastoral Beaker culture. On the continent, Beaker populations also expanded eastward, back into the ancestral Corded Ware homeland, bringing new people and new artifacts to Eastern Europe, though not overwhelming the older population to the same extent as occurred in the west. Beaker folk also pushed northward into Scandinavia, genetically subsuming the Corded Ware-descended Battle Axe culture that had already eliminated their Funnelbeaker predecessors, setting the stage for the synthesis that would spawn the proto-Germanic tribes of antiquity.

A prehistoric star phylogeny in the north

A key aspect of the Beaker revolution is that not only did it correlate with the artifact in question, a bell-shaped beaker, it also reflected a revolution in the ruling elite; replacement of one patriarchy for another. While Corded Ware male lineages were dominated by R1a, modern Europe’s even more common R1b haplogroup rose in concert with the Bell Beaker explosion of the mid-third millennium. Whereas during the period between 2800 to 2400 BC Scandinavia was dominated by R1a men, today more than twice as many men in Denmark are R1b as R1a (33% vs. 15%), while in Sweden and Norway it’s about 1.3 times as much R1b as R1a. In Finland, R1a is still somewhat more common than R1b, albeit from a very low baseline: 5% vs. 3%. The low frequencies here are due to later demographic turnover in Finland that did not impact Scandinavia proper, the expansion of haplogroup N. This lineage from Siberia is the most common Y lineage in Finland, brought by Uralic speakers some 2,000 years ago. But it is notable that here I1 is the next most common haplogroup, carried by 28% of Finnish men. I1 happens to be the most common lineage in Sweden today, at 37%, and tied with R1b in both Norway, at roughly 32%, and in Denmark, at 34%.