Hans, are we…. the admixed ones?

An unspoken taboo: examining German genetics

Related: The two Indo-European revolutions and Germania’s rise.

You can search the vast literature however you like, but to this day you will not find a single definitive publication on “the genetic history of Germany.” You assemble the story yourself, cobbling together fragments of insight from papers where Germans make an appearance, accumulating a patchwork narrative from the pieces of Mitteleuropa strewn across sundry discussion sections and supplementary tables. A quick Google Scholar search yields 2006’s SNP-Based Analysis of Genetic Substructure in the German Population, based on 70 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across 2,159 individuals. Compare this with a query on Britain’s genetic past for which you will be rewarded with such options as The fine scale genetic structure of the British population, drawing on 2,039 individuals at coverage of over 500,000 SNPs each, and with recorded provenance on every proband down to the county level from both parents and all four grandparents. Of course, you could fairly protest that come on, this is human population genetics where Britain is Britain and punches orders of magnitude above its weight. Compared to everyone. And yet… for mighty little Estonia (population 1,331,000), you have Differences in local population history at the finest level: the case of the Estonian population, with 2,350 high-quality genomes (all 3 billion bases) from all regions of the small nation.

So what gives? Germany is the largest economy in Europe, the lynchpin of the EU. The nation also has several Max Planck research institutes focused on genetics. Svante Paabo’s group is based at one of these Max Planck institutes, and in the space of just 15 years, he and his collaborators, like David Reich and Nick Patterson, have done more than anyone to elucidate the genetic and evolutionary history of our species. Germany’s lack of curiosity about its own human population genetic history and structure is not for want of talent, ability or resources.

Germany, of course, remains haunted by the likes of Hans Günther and his legacy of racial taxonomy that lent Nazi ideology a scientific veneer. The late Nazi race scientist was mockingly but deservedly nicknamed the Rassenpapst (“Race Pope”). While other scientists, like Nobel-prize winning ethologist Konrad Lorenz, flirted with Nazism, Günther was a key ideological influence on the National Socialist movement’s racial “science.” Where Lorenz later apologized for his party membership and publications that suggested sympathy for Hitler’s ideology, Günther literally denied the Holocaust after World War II and continued writing books advocating eugenics. His prominence owed to works like 1927’s The Racial Elements of European History. Indeed Hitler had six volumes of Günther’s work in his private collection, four of them distinct editions of Racial Science of the German People. Günther’s elaborate racial typologies influenced the Nazi regime’s Nordic supremacist framework, though his view that Germans were racially mixed between various European groups, with only a minority of pure Nordic, was pointedly not promoted.

After World War II, the German nation officially turned its back on Nazi ideology and all its trappings. German rejection of 20th-century nationalism’s demons precluded any further inquiry into the origins of the German volk. And yet science progresses, just as surely as medicine or technology. At some point, it would be in even the most wary, risk-averse Germans’ interest to consider the reality that human genetics has long since become a modern science that sheds light on human history with almost miraculous depth and precision, and retains no material connection to the dark arts of intuitive pseudo-taxonomy practiced by misguided race scientists 80-100 years ago. German physical anthropology’s early 20th-century susceptibility to politics owed to the reality that it was neither fundamentally scientific nor governed by any of the domain’s built-in checks or ethos of provisionality and humility. It was thus tragically suggestible and easily reshaped to the given moment’s Zeitgeist; a “science” poorly anchored in reality proves easily hijacked for bias-fueled caprices and passing preferences.

Human population genetics’ enduring neglect in Germany is an unfortunate omission that hobbles our understanding of Europe, redacting the dramatic events playing out at center stage of an entire continent. You can read The genetic history of France, Poland, Italy and Scandinavia, but the literature offers nothing comprehensive on Germany, which arguably plays anchor to the vast span of Northern Europe.

Germany stands athwart the European continent, a north-south axis transecting the North European Plain and ascending up into Central Europe’s highlands. From its northernmost regions came the barbarian Germanic tribes of antiquity, all of whose roots date to the Nordic Bronze Age 4,000 years ago. Southern Germany may also have been the Celt urheimat (cradle of the Urnfield and Hallstatt cultures 2,500 to 3,500 years ago), while eastern Germany has witnessed the waxing and waning of Baltic and Slavic peoples over the last few millennia. It was in western Germany 4,600 years ago that the late Corded Ware Indo-Europeans became the Bell Beaker Indo-Europeans, these latter destined to bring much of the continent under their sway. It was the Bell Beakers who brought Indo-European languages to Spain, the British Isles, Italy and France. It was the Bell Beakers whose expansion and diversification would later give rise to the western Indo-Europeans; the Celts, Italian tribes like the Samnites, Umbrians and the Latins, and lastly, to a great extent, the Germans.

At the heart of Europe

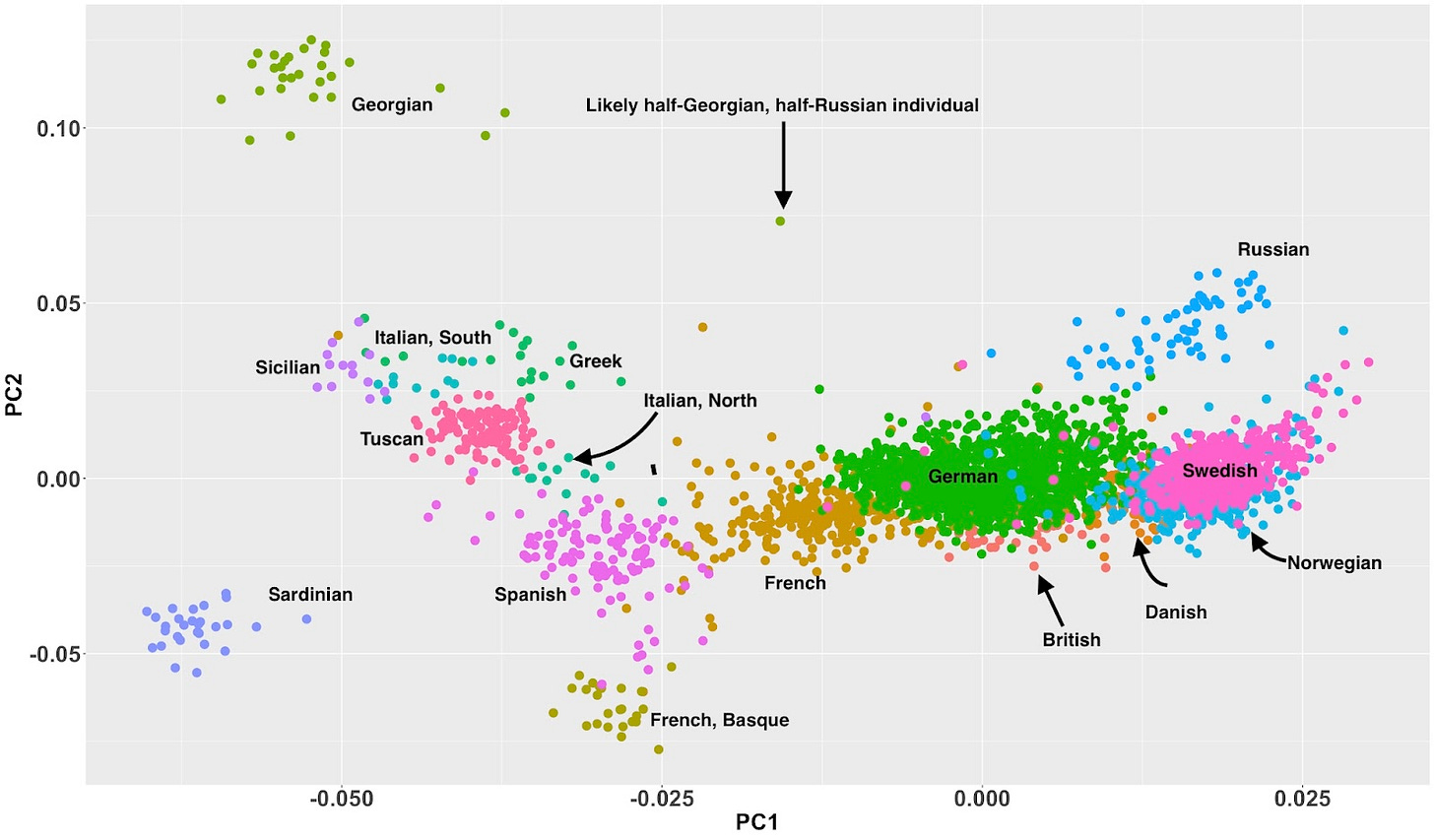

There is precious little the rest of us can do if no institutions have an appetite to delve into ancient DNA from German sites. And even for questions on recent German ancestry, public genetic datasets of ethnic Germans are few and far between. But I have worked with genetic genealogists and so have access to some private collections. To dig into questions of German genetics, I curated a collection of 1,290 unrelated American individuals with ~100% Northern European ancestry who claim four German-born grandparents. By pooling these data with that of various other European genetic projects I assembled a dataset with 3,114 individuals, all genotyped at a common 209,000 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Running principal component analysis (PCA) on the dataset to pull out the two largest dimensions of variation (PC1 and PC2), you see in the first PC visualization above that the European nationalities segregate out reasonably well. PC1, the x axis, explains about 2.7 times more of the data’s variation than PC2, the y axis. This aligns with expectations; most of the variation in European genetics is north vs. south, rather than west vs. east. This is particularly exaggerated by the very low genetic diversity in Northern Europe; the expanse between the Urals in the far east and France’s Brittany in the west is exceptionally homogeneous. Two parallel factors account for this: geography and history. From European Russia’s eastern edge to northern France, the North European plain extends unbroken save by rivers. This facilitates easy movement both west to east, and east to west. The second fact, related to the first, is that some 4,500-4,900 years ago a series of massive migratory waves broke out of Ukraine’s Pontic steppe. The first wave were Yamnaya nomads in their wagons, but a second radiation of Corded Ware agro-pastoralists followed; these latter still emerged out of a predominantly Yamnaya culture and genetic substrate. The Corded Ware arose in the forests to the north of the core Yamnaya homeland, but stand distinct, having assimilated Neolithic Globular Amphora genetic contributions in Poland and Belarus.

As the Corded Ware population moved westward, first into what is now modern Germany, and then into northern France, further admixture with Neolithic farmer populations followed, but the dominant element remained Indo-European, first as Corded Ware, and later as its Bell Beaker descendant. The majority of today’s Northern European ancestry has had less than 5,000 years to diversify, because it is shared across this migration, much of the variation merely reflecting the fluctuating levels of admixture with local farming populations along the drive westward.