Eternally Illyrian: How Albanians resisted Rome and outlasted a Slavic onslaught

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #3

For 2025, I’m trying out a new occasional feature for paying subscribers, the Unsupervised Learning Journal Club: I’ll offer a brisk review and consideration of an interesting paper in human population genomics.

In the spirit of a conventional journal club, at the end of each post, interested subscribers can vote on next papers to review. I’m open both to covering the latest papers/preprints and reflecting back on seminal publications from across these first decades of the genomic era.

If your lab has work we might like or you otherwise want to suggest a paper for me to cover, feel free to respond to this email or comment on this post.

The first two editions were on plague and the genetic evidence for matrilineal Celts.

Wealth, war and worse: plague’s ubiquity across millennia of human conquest

Where Queens Ruled: ancient DNA confirms legendary Matrilineal Celts were no exception

Free subscribers can get a sense of the format from my ungated coverage of two favorite 2024 papers:

The other man: Neanderthal findings test our power of imagination

We were selected: tracing what humans were made for

Unsupervised Learning Journal Club #3

Today’s paper is Ancient DNA reveals the origins of the Albanians. It comes out of Alexandros Heraclides’ lab at the School of Sciences, European University Cyprus, in Nicosia, Cyprus. and appeared as a preprint at bioRxiv on June 7th, 2023. The first author is Leonidas-Romanos Davranoglou.

Scions of Illyria

In 271 AD, the Roman Empire consisted of three constituent political entities. In the west, the old provinces of Gaul and Britannia were ruled as the “Gallic Empire,” formed when the usurper Postumus seized them from the forces of Emperor Gallienus. In the east, Queen Zenobia, a noble from the city of Palmyra, led the old provinces of Egypt, Palestine, Syria and the heart of Anatolia, as the Palmyrene Empire. The Roman Empire proper: Iberia, Italy, the Balkans and western Anatolia, plus all of North Africa west of Egypt still remained the largest and most powerful state in western Eurasia, but at that juncture, it felt like the Mediterranean was on the verge of disintegration. Inevitable as this eventual rupture might have been, circumstances conspired to forestall it by three centuries, until the armies of Islam swept decisively across the southern and eastern shores of what the Romans called the Mare Nostrum, “Our Sea.” In the meantime, “the Crisis of the Third Century” instead proved a temporary reprieve as a series of strong rulers promoted through the ranks of military officers held the Empire together by sheer force of will.

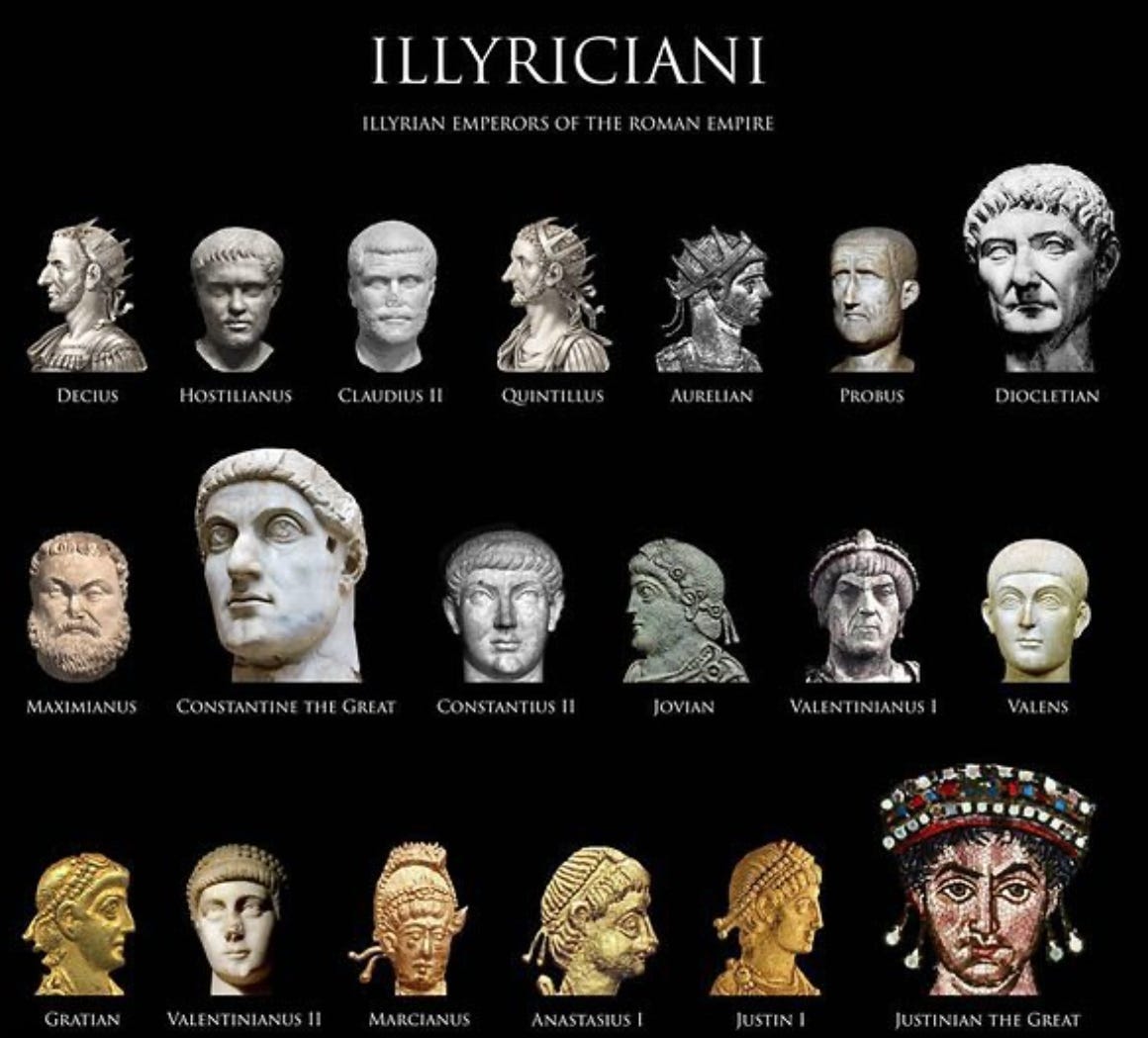

But these saviors of Romanitas did not come from Rome’s old aristocracy; in fact the vast majority hailed from the Roman province of Illyria, roughly today’s Slovenia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo and Albania. This frontier region, in a strategically key position between the west’s expansive Latin-speaking provinces and the venerable eastern territories dominated by Greeks, Egyptians and Syrians, furnished the lion's share of Rome's rulers between 268 AD and 578 AD. The ancient Greeks referred to all the native tribes of the region as Illyrians, hence the Roman-era province’s name. The Illyrians remain culturally and linguistically mysterious to us. When the Illyriciani came to power in the late third century AD, culturally Illyria remained mostly an extension of the Latin-speaking west, with the exception of some Greek-occupied areas in its southern and eastern fringes. But the toponyms and evidence from given names indicate that pre-Roman Illyria was occupied by an Indo-European-speaking people whose languages were only very distantly related to Latin or Greek.

Their languages were likely ancestral to Albanian, which owes half of its lexicon toGreek and Latin, but whose structure resembles neither. Further stymying efforts to better characterize what Illyrians natively spoke is a millennium-long gap in source material; scantily recorded in the first place, Illyrian languages drift out of the historical record entirely during the Roman period, while the Albanian language is nowhere mentioned until 1284 AD, with the oldest document written in Albanian dating to only 1462 AD. Some scholars have argued that Albanian is not even indigenous to the western Balkans, but actually the language of Thracians (ancient Bulgarians) who migrated in the late Roman and post-Roman periods. If true, this would undermine the idea that Albanians and their culture are indigenous to the western Balkans, making them relative arrivistes like their Slav neighbors, whose own tenure dates back only 1,400 years.

Neither linguistics, history nor archaeology has been able to settle the questions around Albanian origins or their connection to the ancient Illyrians who once occupied the western Balkans. Now, 2023’s Ancient DNA reveals the origins of the Albanians brings paleogenomics to bear on the problem, subjecting a massive, multi-millennia dataset from the region to powerful analytic techniques, and concluding that Albanians, and their Illyrian ancestors before them, shared deep roots in the region back to the early Bronze Age and the Yamnaya-descended populations from the Pontic steppe.

The figure above plots modern and prehistoric samples relevant to the Neolithic, Bronze and Iron Age ancestry of the western Balkans, converting genetic distances into geometric ones. It registers individuals genetically shifted toward Yamnaya herders from the Pontic steppe (which lies to the northeast of the Balkans) arriving to the region in the early Bronze-Age (starting approximately 2500 BC). Before that, the region that became ancient Illyria, the southern part of which Albanians inhabit today, was occupied by agriculturalists descended overwhelmingly from the Anatolian farmers who began expanding westward into the Balkans over 9,000 years ago. And notably, the Indo-Europeans who arrived after 2500 BC seem directly descended from the Pontic steppe Yamnaya, as opposed to representing a Yamnaya daughter culture, like the Corded Ware of Poland and Belarus, the direct ancestors of most of Europe’s Indo-European peoples. A large fraction of the western Balkan post-2500 BC samples carry Y chromosomes belonging to the Yamnaya-specific haplogroup R1b-Z2103. This is as opposed to Corded Ware or Bell Beaker, two daughter Indo-European groups who expanded across Eastern and Western Europe respectively, bearing R1a in the former case and R1b-L21 in the latter. Of various potential donor populations to the Bronze and Iron-Age western Balkan samples that could account for their genetic makeup, the Yamnaya from the Pontic steppe are better fits than Corded Ware individuals, who would have arrived from the forests to the northeast, picking up a telltale signature of Eastern European heritage along the way.

This 2023 result, focusing on the western Balkans and the puzzle of Albanian origins, anticipated a more recent finding we examined earlier this year: Ancient genomics support deep divergence between Eastern and Western Mediterranean Indo-European languages. This latter preprint shows that the pattern clear in Albanians and the west Balkans applies to the Greeks and Armenians as well: those Indo-European languages descend directly from that of the Yamnaya, instead of being mediated by a Corded Ware daughter language.