We are what we speak: Indo-European phylogenetic and linguistic trees concur

2024’s biggest ancient DNA findings flesh out Proto-Indo-European trunk, branch and roots

The ancient-DNA era for the human species is not yet 15 years old. It kicked off with the 2010 paper Paleo-Eskimo genome (followed by blockbusters on Neanderthals and Denisovans). Today, remains from tens of thousands of ancient humans offer us decipherable DNA information, each contributing to fill in gaps in our understanding of prehistory.

No matter the brilliance and insight of its practitioners and theorists, human prehistory’s age of genetic inference, when we were limited to examining modern genomes to learn about ancient peoples, was like trying to comprehend the world’s oceans solely from the activity observable in its brightly lit uppermost layers, the photic zone that reaches down at most about 200 meters. Though some key insights date to the before times, the paleogenomic era after 2010 has been absolutely revolutionary and transformative. Name a superlative, and it probably isn’t strong enough.

2024, year 14 of our ancient-DNA golden age if you’re keeping count, was no exception to the relentless pace of revolution and transformative progress in the field. From my vantage, three topics charted particularly spectacular gains this year. As we settled into 2025, I’ve shared my picks for 2024’s most exciting leaps forward in ancient DNA.

In third place, my pick was a September 2024 preprint I’m confident will prove a landmark in the field. It takes ancient DNA far beyond phylogeny, throwing open the gates to vast new landscapes of evolutionary dynamics. Humans are an expansive species that has spread across the planet, adapting to every locale, and this paper now turns our long history into one of evolution’s premier laboratories.

In second place, a blockbuster paper published in Cell’s September 2024 issue, shed important new light on our Neanderthal cousins: they were diverse, just like us. For hundreds of thousands of years, Neanderthals occupied both all of Europe and parts east, so it stands to reason that they would be at least as diverse as our species. But this new ancient DNA finding demonstrates that in some ways Neanderthal social behavior also looks startlingly foreign to our sociable clan; the remains found demonstrate that they maintained genetic and cultural separation for tens of thousands of years from even their nearest Neanderthal neighbors.

And today, my favorite findings of all, out of a couple different labs, flesh out our Indo-European phylogenetic tree with a phenomenal amount of new detail.

Some academic questions linger unresolved for centuries, subject to generations of scholarly dispute and research, only to be settled overnight, almost wholly without fanfare. One of my life-long favorites reached something of a quiet scholarly resolution in 2024, just shy of 240 years of debate and research across multiple academic disciplines. That question, or bundle of them ran roughly: was there one original Indo-European people, and if so, did they really do all this, and if they did, are we… them?

In 1780’s Calcutta, Sir William Jones was a 30-something British polymath with a particular talent for linguistics whose straitened financial circumstances had forced him to set aside full-time study of the world’s languages, take up law and accept a judicial post there. One day in January of 1786, he stood before the Asiatick Society of Bengal (which he had founded within months of arriving on the subcontinent and of which he remained president until his death) and observed that Sanskrit struck him as sharing stronger affinities with Greek and Latin than could be explained by pure coincidence. He speculated that these three ancient languages shared a common root and further mused whether they were also related to Persian and the Gothic and Celtic languages.

Jones knew what he was talking about. He had grown up speaking Welsh and English. At Harrow he so excelled at Greek and Latin that the headmaster readily admitted the boy knew more Greek than he did. A classmate recalled that Jones could eventually imitate Sophocles so dexterously, his invention seemed the authentic article. He studied French and Italian as vacation amusements. And also began Arabic and Hebrew as a teen. By the time he was at Oxford, his Latin and Greek studies were so advanced, he found little to sink his teeth into at lectures or in tutoring. So he added a couple more contemporary Romance languages: Portuguese and Spanish, dabbled in German and then really threw himself into Persian and Arabic. He acquired Persian fluency on his own (and successfully enough that the many books he authored included translations from Persian into French). But for (non-Indo-European) Arabic he hired a Syrian he found in London to come teach him the language in Oxford.

Even though his family circumstances left him unable to pursue his linguistic studies vocationally, by his 40’s Jones could speak eight ancient and living languages fluently, had studied eight more, by his reckoning “less perfectly” and counted a final 12 “least perfectly” studied. It bears noting that these final 12 in which he minimizes his accomplishments include both the Welsh of his childhood and Chinese which he knew adequately to have published original translations of two classical Chinese poems from the Book of Odes.

In his judicial post in Bengal, exasperated by local jurists handing down contradictory rulings when interpreting the same Sanskrit source text, Jones seized that professional excuse to intensively tackle Sanskrit so he could interpret the texts for himself. No surprise that in under a decade, he learned it deeply enough to produce translations of both juridical texts and literature, some of the latter attaining acclaim in Europe, delighting the likes of Goethe. It was this recently begun deep study that led him to observe at that Asiatick Society meeting that that ancient language’s affinity to Latin and ancient Greek was too strong to:

possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists; there is a similar reason, though not quite so forcible, for supposing that both the Gothic and the Celtic, though blended with a very different idiom, had the same origin with the Sanscrit; and the old Persian might be added to the same family.

Jones was not the first to note this family resemblance. Since the 1500’s, Europeans visiting India had recorded similar observations; Thomas Stephens, an English Jesuit, wrote in 1583 that the native language of Goa, Konkani, seemed to have similarities to Greek and Latin. A couple in the 1600’s are even said to have sorted their candidate branches with more prescience than Jones. But Jones’ insight that those ancient languages sprang “from some common source which, perhaps, no longer exists” is credited with founding the study of Comparative Linguistics.

Jones had another enduringly powerful insight. He asked why. Raised speaking Welsh and English, among the Indo-European language family’s geographically westernmost exemplars (only Portuguese, Gaelic and Galician originate further west), he now found himself in Calcutta, 8,000 miles distant as the crow flies, among speakers of its very easternmost exemplar, a tongue whose uncanny familiarity even a far less prodigious linguistic talent than Jones could readily have seen.

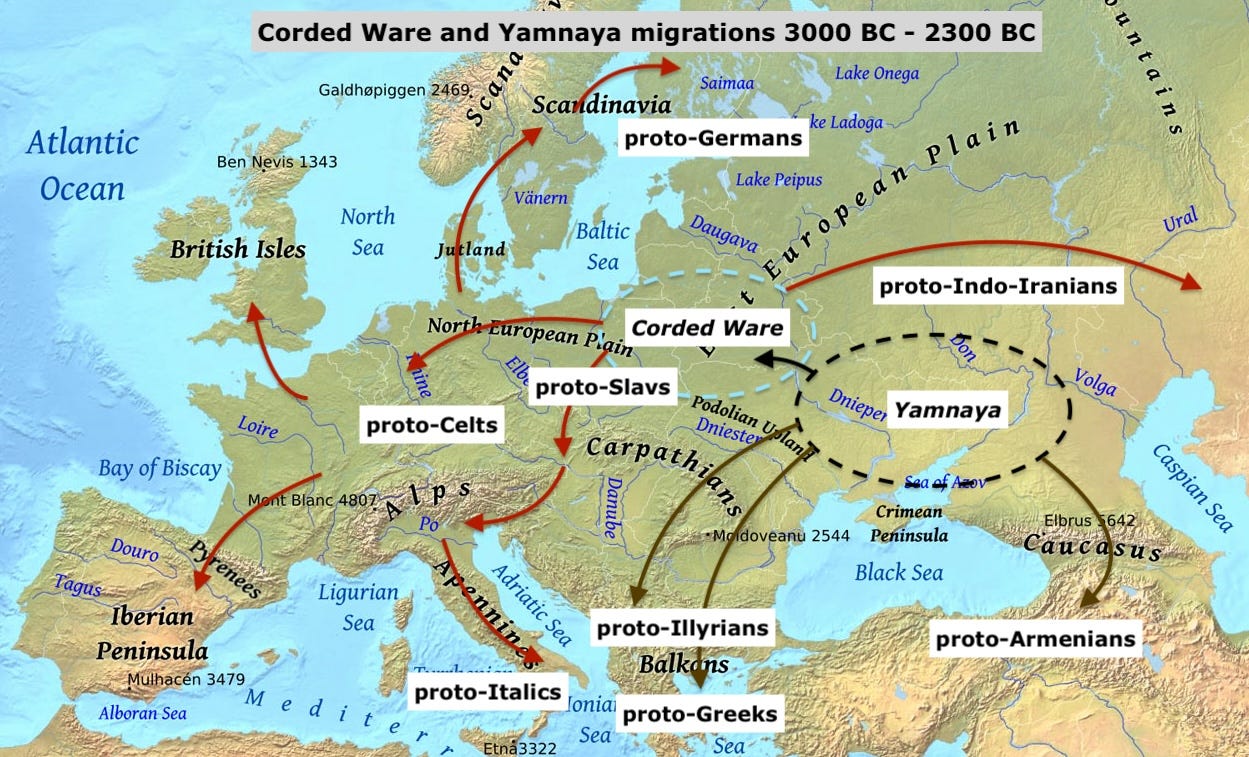

Why, Jones asked, did these people halfway across the continent in some steamy tropical outpost speak a tongue so transparently descended from a shared root with his own? His hypothesis? The region had been conquered, subject to an “Aryan Invasion.” In this surmise, Jones was right. Indo-Aryans, whose ultimate roots go back to Yamnaya pastoralists from the grasslands east of Ukraine’s Dnieper river, did conquer northern India, leaving their stamp ever after on its languages and culture. Their cousins and descendents likewise conquered and reshaped every corner of the European continent, reaching as far as the Levant and points as far east as western China, while a closely related group swept across Iran.

Jones discerned the first outlines of a complex, copiously branching tree’s shadow. Refining the niceties of that shadow’s structure has been the work of linguists and philologists in the centuries ever since. But, Jones put his finger on another huge question for our species. Did that branching linguistic shadow faithfully reflect an actual historical and biological tree? If it did, the ghost tree would represent thousands of years of our species’ detailed demographic history. And its structure would be written not just in our grammar and our vocabulary, but in our genes. As Charles Darwin put it almost a century later:

If we possessed a perfect pedigree of mankind, a genealogical arrangement of the races of man would afford the best classification of the various languages now spoken throughout the world; and if all the extinct languages, and all intermediate and slowly changing dialects had to be included, such an arrangement would, I think, be the only possible one…this would be strictly natural, as it would connect together all languages extinct and modern, by the closest affinities, and would give the filiation and origin of each tongue.

But just a few decades ago, we still didn’t know for certain whether the demographic history written in our DNA would draw a tree that bore any resemblance to the linguistic tree’s shadow model. Though genes and languages both pass from parent to child, genetic transmission is always vertical (parent-child), while linguistic transmission can also be horizontal (peer-to-peer). Language’s inherent flexibility kept scholars debating into this century whether Indo-European languages had diffused via memes or genes. But now with a 2024 crop of blockbuster Indo-European papers and preprints, I think it’s fair to say we have answered the biggest questions Jones raised and are in the late stages of settling most of the minor outstanding ones.

We know now that our genes and our words concur. Far more than recent generations of scholars predicted. We actually kind of are what we speak. But ancient DNA has taken us further still. The tree of our demographic history is an often startlingly strong match to historical linguistics’ shadow tree. And now, 2024 has brought a surfeit of results in two high-impact papers, leaving us a stack of refinements and details with which to update our models. Importantly, we have just confirmed a crucial new detail of both our linguistic and phylogenetic trees’ early branching in Europe. We also now know when and where on the steppe the massive trunk first emerged as a fortuitous little sprout. And amazingly, researchers are even now down in the roots of that tree, identifying the exact strains of heritage that coalesced in a demographic sprout fated to send branches across most of Eurasia.

One tree prefigures another

Although linguists, historians and archaeologists have puzzled over the Indo-European languages’ origins and interrelationships for centuries, it was only in the 1990’s that the discipline of genetics could finally hope to contribute, examining the biological interrelationships of human populations. But that era’s phylogenetic trees, based on only a few dozen markers, were poorly supported compared to the robustness of the language trees linguists had by then been refining for centuries.

Until the Human Genome Project’s completion in 2000 and paleogenomics’ full emergence around 2010, genetics was just some excitable upstart asking big questions but unequipped to contribute its fair share of definitive answers. Today, with tens of thousands of DNA genotypes and sequences from ancient humans, dating from 400,000 to less than 4,000 years ago (the later date right at the doorstep of European history), the field is, if anything, overcompensating for its late start.

In the decade between 2005 and 2015, ancient DNA went from one of Leonardo's theoretical flying machines, a glimmer in Svante Paabo’s eye, to a B-17 Flying Fortress carpet-bombing the landscape with data, results, answers and further questions. And in the decade since, scientists have been refining with ever more precision the map of relationships between extinct and modern populations, one ancient subfossil (a fossil with retrievable organic material from which one can extract DNA) at a time. Every further genome yields millions of genetic markers and contributes to the reconstruction of a vast, detailed genealogy of our past. Every new set of ancient remains on an archaeological site is now a potential node on our vast genetic tree, one individual’s pedigree stretching back into prehistory like a fan’s delicate pleats unfolding.

In 2015, only five years into the paleogenomic era, two research teams independently published blockbuster findings that in the period just after 3000 BC, right when scholars like archaeologist Marija Gimbutas had long argued for Indo-European languages expanding into the continent, Europe did indeed see a massive demographic turnover. But whereas Gimbutas’ intellectual heirs, like David Anthony, had theorized a mostly elite migration that would have registered at most a modest genetic impact, while wholly overhauling linguistic patterns, genetics told us that actually across much of northern Europe over half of ancestry was replaced. Today, scholars broadly agree that the Pontic steppe’s Yamnaya people, who contributed this new ancestry, both spoke proto-Indo-European, and aggressively expanded all across Eurasia beginning around 5,000 years ago, overnight shouldering aside venerable Neolithic civilizations from Britain to Central Asia. Between 3000 and 2300 BC, the Yamnaya and their descendents substantially replaced the indigenous peoples across the European continent’s width and breadth.

But those leaps forward in knowledge, helping rule out alternative models to the Indo-Europeans’ steppe origins, were only the beginning. Recent scholarship has charted a breakneck pace of new discoveries and 2024 saw particularly powerful advancements in our understanding of Yamnaya origins and their deep past. Researchers finally obtained data resolving once and for all who the precise antecedents of the proto-Indo-Europeans were. And at the same time, paleogenomicists charted new ground in a key, more recent epoch from 3000 BC, toward the precipice of European history a couple millennia later. Long an inscrutable black box of linguistic (and associated demographic) development, that era now begins to give up some of its secrets; we start to discern certain proto-Indo-European descendants’ branching trajectories of intermediate development as they progressed towards the languages we have known ever since.

Here, I will dive deep into the two groundbreaking 2024 papers (and reference a couple other worthy ones along the way) that mark some of the field’s greatest yet leaps forward. One exciting dataset has proven how, as steppe as European populations might consistently be, one unique cluster of major European populations had their own distinct way of becoming steppe, their wave of undeniable Yamnaya invaders having brought measurably distinct genetic (and linguistic) inputs at a completely different point in time than the rest of Europe’s. This elucidates essential structure in our trees we have been awaiting for decades.

But first, let’s consider two big questions Indo-European studies could barely hope to ask before 2024. Nearly 240 years ago, Jones posited proto-Indo-European, our prolific linguistic tree’s massive unitary trunk (and mused whether its subsequent spread had been propelled by an associated people’s conquests). Today we know that people were the Yamnaya of the Pontic steppe and we can ask both who they were before they were Yamnaya, and where they came from. This latest research takes us deep into the prehistoric genetic roots of a people on the precipice of overrunning much of Eurasia genetically and culturally, all while fatefully seeding the languages now natively spoken by some 46% of humanity.

Exploring our roots, with a little Hittite assist

It was ancient DNA in the seminal 2015 papers that finally confirmed that the Yamnaya people, so named for the imposing pit graves beneath their kurgan burial mounds that have always announced their existence to posterity, themselves propelled the Indo-European languages’ explosive expansion. The massive genetic signal also indicated that overwhelmingly, demographic replacement was the vector for the languages’ spread. Yamnaya genes represent nearly half of Northern Europeans’ ancestry today, around 30% of Southern Europeans’, and some 10% of South Asians’.

But what came before the Yamnaya? Every people has a past, even the ones who descend on human history like a fury seemingly out of nowhere. Until recently, we hadn’t nailed down who the fateful precursors of the Yamnaya themselves were: the pre-Indo-European calm before the proto-Indo-European maelstrom. Archaeologists and paleogenomicists have been puzzling over this for the last decade, since those first 2015 results from Yamnaya burial mounds established their seminal role in Eurasia’s Indo-Europeanization. Were the Yamnaya an ancient indigenous people of the Pontic steppe, sprung from the banks of the Dnieper during the icy Pleistocene, or themselves a fateful recent synthesis of steppe and tundra peoples? Did they have connections further afield, perhaps in Anatolia or Iran?

Those first results in 2015 offered some key clues; it was immediately obvious the Yamnaya were wholly unrelated to Europe’s Mesolithic foragers or its Neolithic farmers to the west. Their connections lay to the northeast and south, far beyond Europe’s borders. The closest match for roughly half the ancestry across dozens of Yamnaya genotypes traced back to an ancient culture geneticists call Eastern hunter-gatherers (EHG), occupants of the Russian tundra and woodland at the end of the last Ice Age 11,500 years ago. The 2015 findings also demonstrated that these foragers had descended from prehistoric Siberian hunter-gatherers migrating westward out of Asia who mixed with groups of indigenous European hunter-gatherers (WHG) after crossing the Urals.

And that wasn’t the only prehistoric population detected in the Yamnaya’s ancestry mix. After the Ice Age, EHG populations in modern Ukraine and points north and east mixed with Caucasus hunter-gatherers (CHG), migrating northward from the fringe of the Near East. In the 2015 model, this CHG heritage, related to Iranian farmers further south, accounted for most but not all Yamnaya non-EHG ancestry. A 2022 paper later established minor but detectable levels of Neolithic Near Eastern farmer ancestry accumulating in the Yamnaya after the CHG inflow, perhaps only a few thousand years before their expansionary phase five millennia ago. This suggested immediate Yamnaya connections to people in all directions save for to their west, in Europe proper.

So with those preliminary findings, paleogenomics finally injected a first sense of Yamnaya genetic antecedents on a coarse Eurasia-wide scale, but still nothing to connect precisely, specifically and robustly to a culture and people from archaeology. That question had remained cloudy since Gimbutas systematized the steppe theory in the 1950’s.

Now, nearly a decade after those provisional estimates, a breakthrough 2024 preprint, The Genetic Origin of the Indo-Europeans, catapulted our understanding forward, pinpointing exact ancient populations clearly ancestral to the Yamnaya, thanks to a cache of extremely early samples with significant explanatory power. The new batch of ancient DNA from a region just east of the Yamnaya heartland, and dated only a few thousand years before the Yamnaya’s first early expansion, finally delivered perfect statistical fits for their direct antecedents. The samples’ time transect, superior quality and unprecedented volume enabled models on a scale to really outline the geographical and historical dynamics culminating in the Yamnaya as a people, both ethnoculturally and genetically.

The 299 new samples, mostly dating to the fifth millennium BC, come from an expanse stretching from Russia’s lower Volga region, north of the Caspian Sea down into the northern Caucasus. The authors pooled these samples into a single population they termed the “Caucasus Lower Volga” (CLV) cline for its gradient of mixed and variable genetic ancestry. Across this zone of genetic and cultural interaction, over 6,000 years ago, local societies seem to have become a powerful vortex for gene flow sweeping in from the north (Volga headwaters), south (Caucasus mountains) and east (toward the Kazakh steppe and beyond), absorbing varying contributions from EHG, CHG, Near Eastern farmers and western Siberian foragers. This tracks with and refines those earlier genetic analyses of the Yamnaya that were limited by more primitive methods and lower-quality samples at a scale of dozens not hundreds.

But confounding widespread suspicions that the Yamnaya had entirely indigenous roots in their homeland prior to their fateful expansions, the CLV homeland on the banks of the Volga actually lies 600 miles east of that core Yamnaya zone in Ukraine’s lower Dnieper region. And crucially for our Yamnaya backstory, at some point in the centuries before 4000 BC, a single genetically distinct and homogeneous population from within that CLV zone migrated west to the lower Dnieper basin. There, they encountered indigenous Ukrainian foragers of predominant WHG origin, and assimilated them, over the next few centuries begetting another novel genetically homogeneous culture, whose ancestry ratios crystalized at around 75% CLV and 25% forager-derived WHG. So while the Yamnaya did, as expected, bear some deep Dnieper-zone roots, those were in an entirely minority ratio. The Yamnaya’s immediate origins now seem to derive from two peoples, the minority one previously identified: Neolithic-period Ukrainian hunter-gatherers local to the area. And a newly characterized intrusive eastern majority with roots in and around the southern Volga basin that had just migrated across hundreds of miles of open steppe. And finally, with these results, we have matches to ancient archeological cultures within the CLV to sort through; groups like the Volosovo, the Netted Ware, Bug-Dniester, Dnieper-Donets, Sredny Stog, Kamskaya and Khvalynsk cultures.

The Hittite mystery resolved

But what does this detailed new backstory tell us about the saga of Indo-European languages? It provides a strong clue about where proto-Indo-European’s ancestor itself came from, since Yamnaya genetic proportions skew overwhelmingly (3:1) to the CLV. This data point is already persuasive on its own, but another unforeseen ancient-DNA result within the preprint makes the case even more forcefully. While excavating those deep Yamnaya roots, the authors stumbled onto an unexpected nugget of gold: the genetic origins of the Hittites, the Late Bronze Age’s lone other international superpower alongside Pharaonic Egypt.