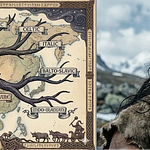

On this week’s episode of Unsupervised Learning Razib covers the archaeology, genetics and history of the horse. Dogs may be man’s best friend, but for thousands of years horses were humanity’s most valuable domesticate. While pigs, cattle and goat were essential elements of the world’s subsistence economies, the horse in its military roles was a luxury good, with Chinese emperors sending delegations to Central Asia in search of “heavenly steeds.”

But while dogs have been humanity’s sidekick for at least 20,000 years, and cattle and caprids for about 10,000 years, the horse is a relatively new addition, tamed on the Central Asia steppe only some 5,500 years ago. But despite their late entrance, horses quickly proved economically critical, opening up trade routes, increasing farming productivity and remaining weapons of war down until the last futile Polish cavalry charges in 1939 against invading Nazis. The horse’s role as a loyal steed was not inevitable; repeat attempts to domesticate tropical zebras have failed, while most other Eurasian megafauna, from moose to elephants, remain wild.

The horse is part of the “secondary products revolution,” with high-fat milk and manes that can be refashioned to adorn human helmets, but just as importantly it was a pre-modern information technology revolution. Mongolian cavalry-messengers were able to cut a year-long trek across Eurasia down to a month. And between about 300 AD and 1500 AD, mounted cavalry dominated the Eurasian continent, driving the emergence of new empires and hastening the collapse of old ones. Since its domestication on the Pontic steppe in 2500 BC, which may have saved the species from extinction, the horse has played a critical part in world history, only really finally passing into obsolescence on the farm, the road and the battlefield in the past century and a half.