Under pressure: the paradox of the diamond

What obscure Jewish subgroups teach us about Ashkenazi and Sephardic flourishing

Related: The eternal wanderers: Sephardic Jewish genetics and culture and Ashkenazi Jewish genetics: a match made in the Mediterranean.

Person for person, it’s hard to think of a group that has contributed as disproportionately to human knowledge and innovation as the Jewish people. Just consider that Ashkenazis have shared in fully twenty percent of Nobel prizes awarded thus far. In recent posts, armed with genetics’ most up-to-date insights, I’ve been delving first into the story of Ashkenazi Jews, which I see above all as an extraordinary demographic triumph, followed by that of the Sephardic Jews, which I read as a tale of a particularly universally adaptable culture. (I highly recommend these paid-subscription-only pieces as background for any interested free subscribers.) I note in passing how trends suggest the demographic balance will shift between the Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish populations in coming decades. Regardless of their current ratio though, between these two massively influential groups, we account for the vast majority of Jews alive in the world today.

But in this piece I want to turn my attention to the small fraction of groups whose stories don’t fit neatly under either umbrella. Around the world and lost to the recent historical past are found fascinating communities of Jews in the most unlikely locales. Their very deviation from the well known storylines might tell us more about those two massive human success stories than the Ashkenazim and Sephardim do themselves. Why did Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions flourish on such an ultimately massive scale while other isolated Jewish groups much more often faded into the surrounding population, often leaving only the faintest genetic signatures in gentiles? In some cases, like China’s Kaifeng Jewish community, almost no trace remains. Or consider India’s and Africa’s unique isolated Jewish communities, whose practices have diverged so much from traditional Judaism. What do their contested identities tell us about what it means both to be Jewish and to flourish as a community in that unique identity?

Ultimately, the stories and struggles of these most marginal Jewish groups leave us to ask whether a key ingredient in the outsized success of the most ascendant Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jewish communities over time might have been their distinct and clearly delineated minority role within majority Christian or Muslim nations. And why?

On the edge of the world

Today in the modern state of Israel nearly 100,000 citizens are both Jewish and of Indian descent. They are a diverse bunch, some being relatively recent migrants to the subcontinent within the last few centuries, and others retaining more mysterious origins, but possibly dating back 2,000 years to the scattering after the two Jewish rebellions against the Roman Empire. Indian Jews with more recent foreign ancestry usually trace their origins back to medieval and early-modern arrivals from the Middle East and Europe: Mizrahim, Sephardim and in a few rare cases even Ashkenazim fleeing persecution, pogroms and the Inquisition. These Jews are familiar and readily recognized by fellow Jews in the West, as they do not differ in physical appearance or custom from communities that emerged out of the Mediterranean and Middle-Eastern milieu. But other Indian-Jewish groups are far more exotic, and in their physical appearance and customs, seem far more indigenously Indian, suggesting more ancient origins, as the passing centuries may have resulted in a deep synthesis with the native societies.

Of the second category, today there are over 60,000 Jews who identify as Bene Israel, and descend from a people who had long been resident on the western coast of India. Traditionally, they share the Marathi language of their neighbors, and within India most have migrated to the city of Mumbai, where they form the heart of the Jewish community. Though their Jewish religious practices have been brought into conformity with world-normative Judaism, the Bene Israel at some point became detached from Rabbinical Jewish practice with its great emphasis on matters of law deriving from Talmud commentaries, instead retaining only vestigial beliefs and customs derived from the Hebrew Bible (for example, circumcision and a few traditional religious phrases).

Most of these Indian Jews now live in Israel, but because of their religious heterodoxies and South-Asian physical appearance, their Jewishness has been questioned by other Israelis. To add confusion to the matter, the Konkanastha Brahmins who originate in the same region of India as the Bene Israel resemble them physically, and some have argued for a connection between the two groups. Could it be that the Bene Israel are Judaized Konkanastha Brahmins?

Though genetics cannot answer matters of Jewish law, it can probe the genealogical connection. The Bene Israel clearly descend from a fusion of a Near-Eastern population and local Indians. Judging by the Judaic practices in the community, and the fact that Bene Israel in genomic analyses yield some fraction of identifiable “Jewish” heritage, that Near-Eastern population was surely Jewish. Whatsmore, the Bene Israel Y chromosomes, their paternal lineages, have a particularly strong Jewish imprint, sharing lineages found among European and Middle Eastern Jews. In contrast, their maternal lineages are overwhelmingly Indian. Overall, on the order of 20-30% of their total ancestry seems to derive from a Middle-Eastern population quite similar to Iraqi and Iranian Jews.

Though the Bene Israel’s religious heterodoxy cast doubt on their Jewishness, their racial distinctiveness was likely the major obstacle to mainstream Jewish acceptance of their authenticity in Israel. While the European foremothers of the Sephardim and Ashkenazim were not Near Eastern, their physical appearance was still closer to that of their husbands than was the case among the Bene Israel. While there were live debates as late as 2010 over whether European Jews carried non-Middle Eastern ancestry, the Bene Israel’s Indian appearance left no doubt as to their mixed origins from the moment Western Jews encountered them.

And the Bene Israel are not the only Jews in India whose racial identity casts doubt on their origins. The Bene Israel were brought back to the mainstream of Judaism through contact with the Jews of Cochin, on the Indian coast to their south. The latter community never lost touch with other Jewish communities. While the Bene Israel are a homogeneous group, the Jews of Cochin are subdivided between “black Jews” and “white Jews.” The latter descend from migrations from the west in the last 500 years, and their Jewish identity is not in doubt. In contrast, as with the Bene Israel, genetics now indicates that the “black Jews” of Cochin seem to have emerged through the intermarriage of Near-Eastern Jewish men with local women.

Today the Bene Israel are conventionally Jewish in their practices, but the historical record and ethnography makes it clear that their religious distinctiveness had become highly attenuated by the 18th century. It is clear that only their proximity to Jewish groups who were still in contact with the rest of the Diaspora eventually brought them back into the mainstream, and prevented them from becoming another of the “Lost Tribes,” fading into the Indian cultural milieu in which they had assimilated to such a great extent. The Bene Israel illustrate how easily Jewish identity becomes tenuous in isolation. It seems to require integration into the broader cultural network of the Diaspora to maintain practices and revive identity.

Among the converted peoples

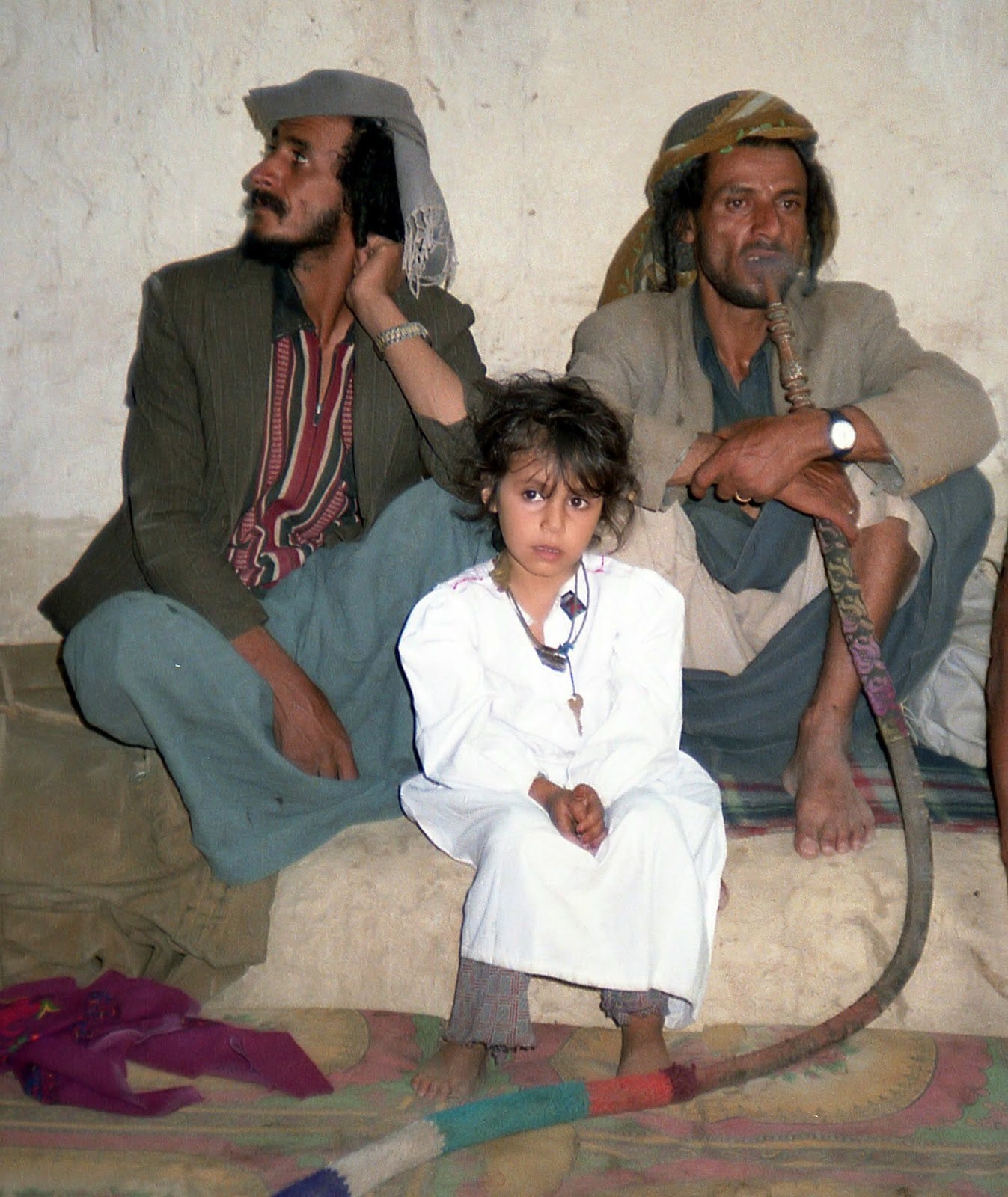

While Indian Jews have been liminal to the Diaspora, the Jews of Yemen in southern Arabia have existed just outside of the core of the Jewish homeland, at a modest remove so as to remain distinct, but close enough so that they have been part of the cultural changes within Judaism over the past 1,000 years. Their own origins date back to Late Antiquity, as for over a century, between 400 and 520 AD, Yemen was ruled by a dynasty of Jewish kings. This was a period of religious ferment and diversity in the Near East, as Christianity was on the march in the Roman world, and Zoroastrianism was resurgent under Persia. In Arabia, pagans, Jews and Christians lived cheek by jowl. The existence of Meccan Jews is attested in the Koran in the 6th century A.D., but there are no indigenous non-Muslims in Saudi Arabia today. But further south, somehow the Jews of Yemen have clung tenaciously to their unique but marginal status down to the present. Their lot was not always easy and often precarious. While the Ashkenazim became bankers to rulers of Europe and the exiled Sephardim held positions in the court of the Sultan in Constantinople, the Jews of Yemen were isolated and oppressed. They were artisans and small traders, whose pride and dignity was in their religious uniqueness, rather than the power or wider influence they wielded.

Similar to the Mizrahim of Iraq and Iran, the Jews of Yemen fell under the cultural sway of the Sephardim when these latter arrived in the Ottoman Empire, though they continue to hold themselves somewhat apart in elements of their liturgy. And, like the Jews of the northern Middle East, they are genetically distinct from their neighbors. Most modern Yemeni Muslims exhibit substantial Sub-Saharan African admixture, while some on the coast have Indian and Indonesian heritage. In contrast, Yemeni Jews are quite homogeneous and their ancestry seems entirely Middle Eastern. And yet, curiously, they are not entirely unique in this; Yemeni Muslims from deep in the highlands also lack African and Asian ancestry.

The implication of these DNA results is that Yemeni Jews are by and large descended from natives of this region of Arabia. They are converts, and their genetic uniqueness is a function of their isolation from demographic currents that swept across Arabia with the rise of Islam. The Yemenis of the highlands, isolated by geography, show the same genetic signature of isolation, as they descend solely from the original inhabitants of the region. This is the nth demonstration that culture and geography are both powerful factors driving genetic distinctiveness.

Does it speak to their Jewishness that the Jews of Yemen likely do not descend from the ancient Judaeans? Not from a religious perspective, as their lineage surely extends back 1,500 years or more to the period when many Arabians were converting to Judaism. Modern Yemeni Jews have been Jewish far longer than their neighbors have been Muslim.

The genetic similarity between Yemeni Jews and their Muslim neighbors is analogous to the case of the Jews of Ethiopia and their Christian Orthodox neighbors. But the instance of the Ethiopian Jews, the Beta Israel, is more fraught. They too are converts. However, unlike the Jews of Yemen, but like many of the Indian Jews, the Beta Israel were dogged by accusations that they were not truly Jews when they arrived in Israel.

Live and become

Like the Bene Israel, the Beta Israel were not Jews who knew the Talmud. Rather, their Jewish practices seem to have derived from the Hebrew Bible, what Christians would call the Old Testament. Second, like the Bene Israel, the Beta Israel are racially distinct from Middle Eastern and European Jews. Like their neighbors, the Semitic-speaking Amhara and Tigre people, this means that their heritage is a mixture of ancient Near-Eastern populations and indigenous Sub-Saharan African ancestry. There is also no detectable affinity between the Beta Israel and the Jews of Yemen across the Red Sea. The Beta Israel are in this way a sui generis people.

There are two views on the origins of the Beta Israel. The first is that they descend from a small ancient community of Jews that expanded through conversion and admixture until the original signal was diluted beyond genetic powers of detection, though their cultural uniqueness remained. The Ethiopian Christians themselves claim a Jewish origin through the lineage of Solomon, whose mythical liaison with the Queen of Sheba produced the ruling houses of the highlands. Unlike the West, Ethiopian Orthodoxy descends from a form of Christianity introduced by Syrian missionaries. Christians in Ethiopia practice male circumcision and adhere to some Jewish dietary laws, including avoiding consuming pork.

But these facts about Ethiopian Christianity suggest an alternative scenario for the emergence of the Beta Israel: that they are Judaizers who emerged in the 1500’s. Judaization usually refers to a process whereby Christians began to adopt practices from the Old Testament. Usually this stops short of adoption of Jewish identity, as Protestant sects like the Seventh Day Adventists integrated many Old-Testament traditions while remaining Christian. But the existence of the Hebrew Bible within the Christian canon consistently results in some tiny minority taking the scripture to its logical conclusion, following God’s commandments to become literal Jews. A famous case occurred in the 9th century AD when Deacon Bodo escaped Christian Europe for Muslim Spain, declared himself a Jew, Eleazer, and began a correspondence with his former co-religionists on his newfound conviction that Judaism was the true religion.

Apostasy was rare, but not a unique event, and fueled worries about Judaization within the Church over much of its history. With the explosion of religious variety during the Protestant Reformation, some dissenters from the Catholic Church began the slow but gradual journey back to Judaism as well, starting initially with rejection of Christian beliefs like the Holy Trinity, but completing their transformation through the adoption of Jewish practices and beliefs. The most thoroughgoing Protestant Judaizers, like the Szekler Sabbatarians of Transylvania, were absorbed by the Jewish communities of Eastern Europe. In the modern world, such evolutions are supercharged in their rapidity. A small number of Tibeto-Burman tribes on the northeastern fringe of India who only recently adopted the Christian religion have now converted to Judaism, and begun to emigrate to Israel. For them, Christianity was simply the first step on a journey that culminated in Judaism within the space of a few generations.

None of these instances themselves resolve the origin of the Beta Israel. But, they suggest even if the Beta Israel were Judaizers, their religious evolution was sincere and not necessarily opportunistic. There was no great benefit in adopting Judaism in 1500 AD in a Christian Ethiopia roiled by the fight to fend off Muslim jihads. Though there are instances of Orthodox Christian Ethiopians adopting the Beta Israel identity, the reality is that these people have inextricably entwined their lineage and posterity with the Jewish people. Their people now form part of the Jewish people.

The “Lost Ones”

While the Jews of Ethiopia were tucked away in the highlands just beyond the edge of the integrated Mediterranean Diaspora, there were Jewish communities so far beyond the horizon that they were entirely forgotten, and unlike the Bene Israel never truly “discovered” before their absorption into the gentile majority. In 1605, the Jesuit Matteo Ricci encountered a group of monotheists in the Chinese city of Kaifeng. Examining their scriptures, Ricci recognized that their central religious text was the Hebrew Bible. These were Jews, and they were quite happy to meet someone who worshipped their own God. Their leader offered Ricci the position of rabbi, so long as he abstained from pork and joined their faith. Ricci dismissed the invitation, and attempted to convince the leader of the community that their messiah was Jesus, and he had already arrived. This intelligence was not embraced, and Ricci parted ways with the Kaifeng Jewish community.

Ricci later concluded that Kaifeng’s Jews would inevitably be assimilated due to their isolation. He observed that the Jews of Kaifeng were distinctive in appearance from their Chinese neighbors, but by the 18th century, European observers remarked that they looked rather like the Han majority. Intermarriage was common, and the leading families entered the Chinese bureaucracy. One prominent Jewish leader reacted with embarrassment when it was observed that his Han-Chinese wife was raising pigs on their property.

Today the Kaifeng Jewish community no longer exists. One of their clans, the Zhang, has converted entirely to Islam. Others assimilated into the Han majority. Yet families remember their origins, recalling that it was customary that they not eat pork or consume shellfish. Some of these are now converting back to Judaism, and even migrating to Israel.

Though the origins of the Chinese Jewish community in Kaifeng are unclear, its position at the eastern end of the Silk Road implies it emerged out of the Persian-Jewish Diaspora, whose trade network once spanned Eurasia. These were the Radhanite traders, whose status outside of the Muslim-Christian dichotomy allowed them to travel more easily than their competitors. But whereas in the Islamic world and in Christendom, Jews were set apart, and occupied a special status as the historical standard-bearers of the primal monotheistic religion which gave rise to Islam and Christianity, in China their uniqueness was self-imposed. Their eventual assimilation into Chinese society would have gone unnoticed had it occurred a few centuries earlier. As it happened, in the 17th through 19th centuries, Europeans arrived as missionaries and traders in China, and recognized the Jewish community in Kaifeng for what it was.

The Kaifeng Jews remind us poignantly that vast numbers of people who practiced the Jewish religion and identified as part of the Jewish nation have long since disappeared, assimilated into other nations. We know this concretely in the case of Spain’s conversos, but genetics implies that many non-Jewish Eastern Europeans also descend from Ashkenazim who at some point converted to Christianity.

These realities, along with the existence of groups just beyond the pale of assimilation like the Kaifeng Jews (or those who were pulled back from the brink, like the Bene Israel), indicate that while skepticism is certainly warranted, we shouldn’t dismiss out of hand far-flung claims of Jewish ancestry like those of the Lemba tribe of Zimbabwe, who were known to have observed dietary customs and strict endogamy resembling Jewish practices. The best genetic data indicates that these Bantu-speaking people, who converted from paganism to Christianity, do have a Middle-Eastern paternal lineage. This may, or may not be Jewish, but warrants further investigation. It is likely that in the near future, genetic tools will allow for the discovery of even more “lost Jewish tribes” in the far corners of the world. Along with pockets of deep and lasting cultural persistence, one of the consequences of the massive geographical reach of the Diaspora is that many gentiles in unexpected corners of the world carry traces of distant Jewish ancestors.

3,000 years of culture and genes

The Jews are a canonical people of the book, and this likely explains some of their success and persistence across the millennia. Books are portable and not as subject to fading and mutation as oral memory. They promote continuity, maintain historical memory and perpetuate identity.

But the persistence of Jewish nationhood, rooted in descent, is also a fact that allows us to explore questions and investigate topics with the tools of genetics. Modern Jews see themselves as descendants of Jacob, and to a great extent, this conviction has been validated, insofar as deep and common Near-Eastern ancestry is evident in Jewish groups from Germany to Kerala. But Jewish endogamy has limits, and the assimilation of gentile women has been commonplace from Europe to Asia and into North Africa. For at least 2,000 years Judaism has espoused matrilineal descent, yet at the genetic level, it has actually been the paternal lineage that binds many Jewish populations biologically. The foremothers of many Jewish populations were clearly converts, just like the Biblical Ruth, who told her mother-in-law that “your people will be my people and your God my God.”

Some Jews, like those of Yemen and Ethiopia, are the product of cultural forces which have driven them to adhere fiercely to Jewish identity in the face of persecution from Christians and Muslims, never mind how tenuous their genealogical claims are. In fact, genetics tells us that they were drawn from the same background as their neighbors, and what separates them and has done for centuries, is their sense of themselves, not their lineage or ancestry.

And yet the examples of the Jews of India and China hint at the possibility that the unique role of Judaism and the Jewish people in Christianity and Islam may have been an important factor in Ashkenazi and Sephardic persistence and flourishing over the last 3,000 years. Beginning with church fathers like St. Augustine, Christians grudgingly accepted that the Jewish rejection of Jesus as the Messiah was part of God’s plan, and rejected the idea that they should be forcibly converted like pagans. Muslims meanwhile tolerated the Jews as a religious minority that had received a legitimate earlier revelation from God.

This explicit recognition of Jewish communal identity as something special in the world of Islam and Christianity did not obtain in India or China, where Jews were just another exotic ethno-religious group among many. Jews did not play any central role in the self-conception of Hindus, Buddhists or Confucians, and the question of their persistence or assimilation was not of great concern. In contrast, though Muslims and Christians accepted Jewish converts, Christian and Muslim societies often looked at converts from Judaism with suspicion. The combination of explicitly marking the Jews as unique and a people apart subject to discrimination, while tepidly tolerating their existence, may have been the equipoise that allowed them to remain cohesive in the Middle East and Europe, whereas they tended to fade away through assimilation in Asia.

When considering Jewish cultural persistence in the West, and even its flourishing, John Maynard Smith and George R. Price's widely applicable concept of an Evolutionarily Stable Strategy (ESS) comes to mind. The subgroups of Jews who have waxed in numbers and contributed so disproportionately to human knowledge and advancement share a broader milieu, where they are subsumed within Christian and Muslim civilizations that grudgingly acknowledge their debts to the Jews. We are so accustomed to training our attention on the well-documented persecution and various horrors the Jewish people have endured as vulnerable minorities over the millennia; it’s easy to miss the strange implication that the cruel caprices of their host societies that cost them so dearly…were only one side of the coin.

Somehow, being officially and permanently marginalized seem to have been the peak background conditions in which Ashkenazi and Sephardic culture proved an ESS. Their persistence as cohesive subgroups with their own distinct and highly creative culture over millennia only reached its productive apogee where they were kept warily to the margins. In the end, where Jewish minorities have been treated with indifference, neglect, or curiosity, they have inevitably become like those around them. Rather than thriving and enduring, they have been swallowed by the majority.

If the glittering cultural, artistic and intellectual achievements that members of the Jewish Diaspora have shared with all humanity are a diamond, created by the vice-like pressure of Christian and Muslim domination, you have to wonder not only what unique contributions we all lost when less enduring minorities, Jewish or otherwise, were culturally and genetically subsumed into their surrounding societies. Incessant external pressure and resistance seem to have proven tailor-made conditions for Jewish culture’s unique makeup to be an ESS that spanned the Babylonian Exile down to our own era, over 2,500 years. I don’t know if there’s any lesson here, other than the timeless one that when it comes to human societies, unintended consequences always seem to get the last laugh.

Razib: I think you could sell these essays to Commentary Magazine.

It is interesting to speculate on the future of the Ashkenazim Sephardim split.

The worlds Jews consists of two large and many very small populations. The large ones are in Israel and North America (I am including Canada here).

In North America, the Jewish population is largely Ashkenazic. But, it is now experiencing a significant admixture with other North American populations via intermarriage. There is also a large and still growing Haredi population. Not many secular Jews will join them, and not a lot of them will leave their communities. But, every Secular Jew's ancestors were traditional. There is more leakage out of the Orthodox community than they let on.

The difference between North America and other environments where Jews have lived is that there is little pressure from the outside keeping people in. OTOH, there is not much reward for defecting.

There is also substantial two way linkage with Israel. There are many Israelis who move to the US and many American Jews who move to Israel.

In Israel, the various communities will blend with perhaps some Haredi holdouts. The existence of separate Rabbinates has been a purely political function. Its relevance was damaged by the last election/government formation. I suspect that if Netanyahu is truly done, the religious parties will lose their grip on power and the secular majority will move to clip the wings of the Rabbinates.

My guess is that the various ancestral communities in Isreal will meld over the next few generations.

Genetically. The two communities will look very different. The Israeli community will be a mix of Middle Eastern and European components. The North American Community will be much more European with substantial admixture from European descended non-Jewish North Americans.

My guess is that the religious cultures will tend to converge. North Americans will appeal to Israelis because of the "cool" factor. But, North Americans will regard Israelis as more authentic.