Two Steppes forward, one step back: parsing our Indo-European past

Ancient DNA closing the book on centuries of speculation and debate

In 1985, I flipped open a dictionary in my elementary school library, and became completely distracted by a map in the front matter illustrating the distribution of modern Indo-European languages. I was nine years old and this was the first time I saw the term “Indo-European.” Both the term and the map perplexed me. Included were the two languages I knew: English and Bengali, the northwesternmost and easternmost of the Indo-European languages, respectively. What could possibly connect them across that vast geographical span? I certainly had never noted any similarities…until I paused to take a closer look. That weekend, library card in hand, I trudged off to the public library, thumbed through the card catalog until I found the entry for “Indo-European,” inspected it and followed it to the linguistics section. I was already a habitué of the adults’ section, but so far, had solely explored the science stacks. That day, I pulled down a tome whose details I scarcely recall, unfamiliar matters of philology mixed with prehistoric speculation. What I do remember to this day is that inside that doorstopper was a wealth of maps, language-family trees and long lists of word-comparisons laid out in tables (what I know now to be swadesh lists). Seeing the similarities in the core words across Indo-European languages explicitly outlined, the scales fell from my eyes. Below are some typical cognates in English, Bengali and Proto-Indo-European (PIE):

Mother, mā and *méh₂tēr

Father, pitā and *ph₂tḗr

Name, nām and *h₁nómn̥

New, notun and *néwos

Nose, nāk and *néh₂s

Door, dorja and *dʰwer-

Mind, mon and *men-

Mouse, mushik and *muh₂s

Serpent, sap and *serp-

Deity, debôtā and deywós

Once you have seen, you cannot unsee.

More than 40% of humans alive today speak an Indo-European language as their mother tongue, some 3.4 billion people (and well north of 50% if you count second-language learners). The top ten are:

Spanish ~484 million

English ~390 million

Hindi ~345 million

Portuguese ~250 million

Bengali ~242 million

Russian ~145 million

Punjabi ~120 million

Marathi ~83 million

Urdu ~78 million

German ~76 million

It is notable that, for raw numbers, being on the margins seems to have redounded to the benefit of expansionist Indo-Europeans. Except for Russian, all top ten Indo-European languages count speakers positioned around the map’s fringes: the Indian subcontinent and Western Europe. In contrast, the Baltic languages, whose domains once stretched some 750 miles from northern Poland to the environs of modern Moscow, are now constrained to Latvia and Lithuania, counting only some 5 million speakers. In the early 20th century, the Indo-European languages’ widespread range inspired theories of world-conquering supermen, but is anyone prepared to claim Bengalis and Portuguese (but not Lithuanians or Armenians) are scions of some super race? Or is it simply that, as luck would have it, the ancestors of those peoples who pushed to Eurasia’s frontiers were better positioned to exploit ecological opportunities than their kin who remained hard by the core ancestral homelands?

The longstanding questions of why the Indo-Europeans rose to prominence and how they did so date back to the 19th century and continue to be debated today, as attested by the existence of entire departments devoted to the study of Indo-Europeans. After nearly two centuries of scholarly fascination with the topic, J. P. Mallory’s seminal 1989 In Search of Indo-Europeans engrossingly captured the field where it then was. A generation later, David Anthony’s 2007 The Horse, the Wheel and Language, became the essential must-read. But it was truly paleogenetics’ post-2010 emergence as a tool to explore Indo-Europeans’ prehistoric population movements that supercharged the rate of new discoveries and fast-tracked revisions of our understanding toward a final draft. Fifteen years later, researchers have settled many long-standing questions that had spawned decades of spirited debate. Early this year, Nick Patterson, an author of the 2015 letter to Nature, Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, told me he felt they had wrapped up most of the major questions, with only details left to be sorted out.

Certainly since the fall of 2020, when I began writing extensively here about Indo-Europeans, our understanding of the dynamics of the origins, emergence and expansion of these people has come an immense distance. I started with pieces on Aryan migration to India and the Yamnaya’s rise in 2021, among many others, before culminating in a January 2025 post celebrating the fruitful relationship between linguistics and genetics in settling the Indo-European question. Today it feels defensible to argue that we have made more progress in the last decade than in the previous two centuries toward understanding Indo-European prehistory.

If I was a schoolboy today, I might look at the map above, grab my iPad and turn to an AI-agent or search engine. And I might immediately find satisfying answers to most of the questions raised by the fantastic geographical range and cultural diversity of Indo-European language speakers. Just as in my own childhood, at this point archaeologists and linguists have been assembling a vast edifice of data and evidence to answer these questions for decades, if not centuries.

But what took these lingering open questions I discovered as an elementary schooler over the finish line as my children were passing through the same ages, was the intervention of large-scale genomics. Ancient DNA samples in hand, geneticists have finally been able to arrange that carefully collected accumulation of facts from linguistics and archaeology on a rigorous phylogenetic and demographic scaffold, creating a theoretical superstructure sturdy enough to finally decide the fundamental question: how did a small group of pastoralists 5,000 years ago so swiftly come to dominate half the Old World?

Between the Dnieper and the Don

For much of the 20th century, a key issue of debate was where the Proto-Indo-Europeans first emerged and from whence they expanded outward until their sphere spanned half of Eurasia. The leading contenders ranged from Germany to India. Historical linguists looking at the word roots shared near universally across Indo-European languages argued that the ancestral population must have lived in a climate with cold winters, and been familiar with both beech trees and salmon, which made Europe or somewhere immediately adjacent most likely.

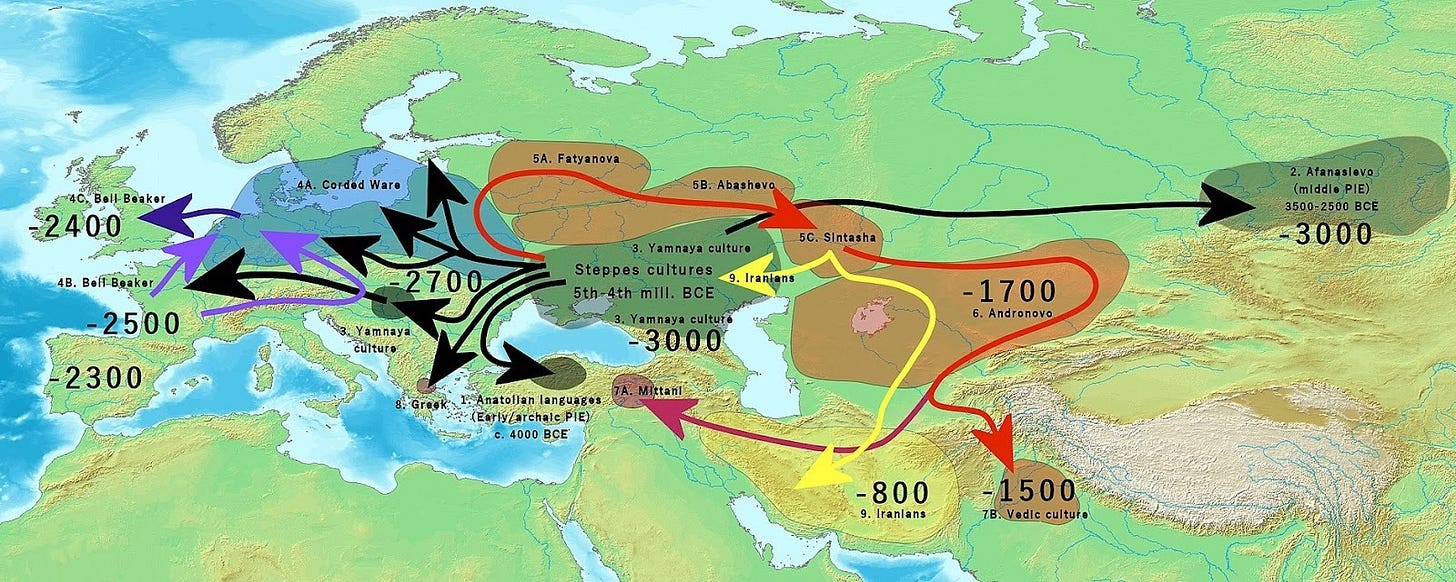

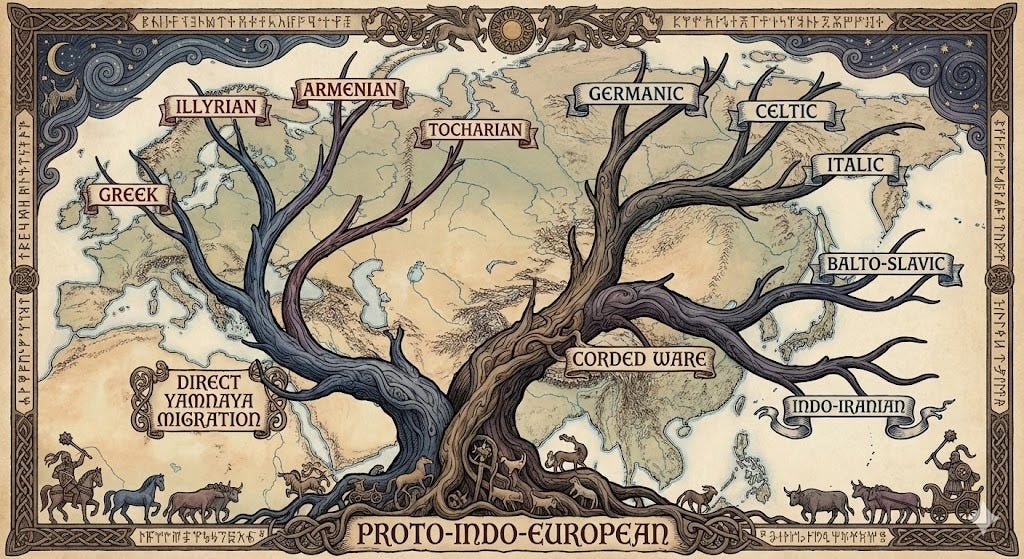

But in the last quarter of the 20th century, archaeologists, led by Oxford’s Colin Renfrew, argued for focusing research on early Neolithic Anatolia, because only the rise of agriculture could have driven the scale of cultural and demographic change that Indo-Europeans had clearly inflicted on their local forerunners. The shortcoming of that theory, from historical linguists’ perspective, was that the Indo-European languages remained too similar to align with the considerable time depth since agriculture’s rise; the Neolithic expansion out of Anatolia into Europe began nearly 10,000 years ago. But beginning in the first decade of the 21st century, a new group of scholars weighed in on the topic, deploying not classical comparative linguistic techniques but computational methods borrowed from phylogenetics. Using lexical data, they applied evolutionary models to understand how modern language distributions and relationships could have emerged, and exactly when they began to diversify from a common ancestor. Surprisingly to the linguistically informed, computational evolutionary linguistics came down on the side of the archeologists, supporting an older origin for Indo-European languages, and so one that aligned well with an Anatolian homeland.

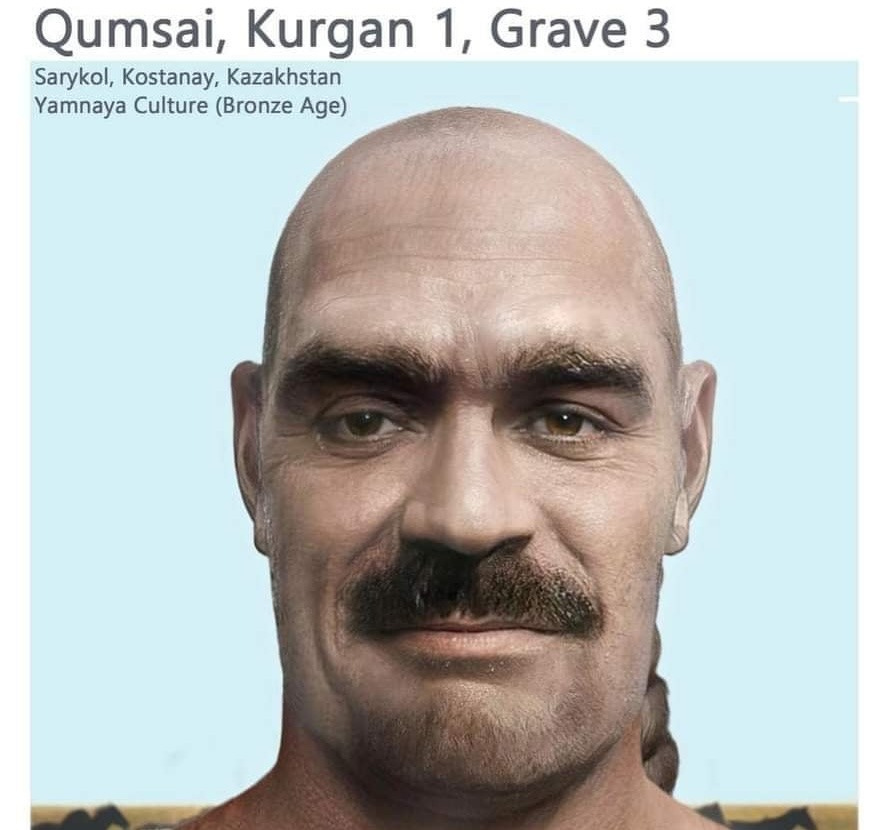

But sometimes simple access to data, plain and clear, can overturn even the most sophisticated, computationally intense modeling. In the mid-2010s David Reich’s and Eske Willerslev’s groups, in the US and Europe respectively, raced to retrieve and genetically test individuals buried in ancient Yamnaya kurgans, those great earthen mounds the Eurasian steppe peoples characteristically placed atop elite graves. With the millennia-old DNA, they ran a battery of analyses comparing the genetics of those Yamnaya to modern and other ancient populations. The results shocked both them and their archaeological and linguistic collaborators: nearly half of Northern Europeans’ ancestry today, a substantial minority of Southern Europeans’ (some 20-40%), and an average approaching 15% across highly variable South Asian populations (with rates rising as high as 35% among Brahmins in certain locales), could be modeled as descended from the fourteen genomes retrieved from nine kurgans.

It’s worth noting that whatever disagreements a faction of linguists and archaeologists might have had with Renfrew’s out-of-Anatolia thesis, they had always conceded that in demographic terms it was likely a cogent argument. Farming supports a much larger population than pastoralism, and so could serve as a more plausible demographic engine for such sweeping patterns of cultural change. And in The Horse, Wheel and Language archaeologist Anthony promulgated the view that Indo-Europeans expanded out of the steppe, expanding on the ideas of his mentor, Lithuanian archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, but even he posited an “elite transmission” dynamic, whereby Indo-European memes were far more impactful than Indo-European genes as small groups of horsemen hurtled westward.

The game changer of paleogenetics here lay not in complex and formal model-building: but in the devastating simplicity of DNA reads. Because not only does that Yamnaya DNA from the kurgans echo down through so many modern human populations; it was immediately apparent that it matched a known Corded Ware burial site in Poland holding literal genetic kin of those in the kurgan mounds. This definitively established that the Corded Ware’s long-debated roots ultimately lay in the Pontic steppe; they were Yamnaya with cultural adaptations and local genetic accretions. Later work from Reich’s group showed 90% population replacement in Britain around 2500 BC, and Kristian Kristiansen, a Willerslev collaborator, has written of the Yamnaya-descended Battle-Axe Culture totally replacing the Neolithic Funnelbeaker society in Scandinavia. Even the Indian subcontinent absorbed a substantial demographic impact, and this in a region that classical observers as far back as Herodotus believed was the most populous on earth (how little has changed!). About 20% of the ancestry of people in the northwestern quadrant of South Asia, home to nearly 300 million people today, can be traced back specifically to the Yamnaya (and fractions even higher if you stipulate steppe pastoralists more broadly). The fractions are lower in other parts of the subcontinent, but even at India’s far southern tip, castes like Tamil Brahmins harbor some 15% Yamnaya ancestry and the least steppe-enriched groups in Southern India still show high single-digit steppe ancestry rates.

A quick back-of-the-envelope calculation aggregating those proportions across all contemporary human populations, Old World and New, estimates the equivalent of some 700 million pure Yamnaya walking among us today. All this from a very small founding population, perhaps just a few allied tribes. A 2025 Reich-lab paper with a large dataset of Yamnaya genotypes estimates an initial ancestral breeding population of about 5,000 at the start of the major expansion phase out of their Pontic steppe homeland into Europe in 3000 BC (up from a population as small as 2,000 in 3500 BC, when we estimate the Yamnaya had truly coalesced as a coherent genetic population cluster). These estimates are usually lower bounds, counting the core minority of individuals who contributed to the genes of future Indo-European-speaking people. But breeding populations don’t tend to be off by more than an order of magnitude; there weren’t 50,000 Yamnaya of whom only 5,000 bred. Using standard rules of thumb, we can estimate some 10-20,000 Yamnaya in total, subdivided between a few tribes. This means 5,000 years ago, with the Yamnaya on the cusp of their world-altering expansion, as few as 10,000 nomads scattered between the Dnieper and Don rivers in what is today Ukraine were about to run the table from the Altai to the Atlantic. Contemporary observers, like their neighbors the Cucuteni-Trypillia people, who built some of the largest towns of the late Neolithic, likely did not see the scattered nomadic Yamnaya as a particularly portentous or formidable horde, and yet within less than a millennium they would go on to reshape the face of the entire Eurasian continent.

Sometimes the evidence is so overwhelming, it fairly demands a final verdict. The flood of ancient DNA and genetic analyses has allowed archaeologists and linguists to reconstruct the shape of the past with a fidelity unimaginable a generation ago. The sequence of migrations is now finally clear, written in genes, and told in the rise and fall of successive peoples. Between 3000 and 2900 BC, a new culture arrived in what is today Poland, long ago detected in archaeology’s traditional fashion by the propagation of a new pottery tradition. These were the Corded Ware, a people who would become the subject of a century of speculation in European archaeology. To the shock of many, it quickly became clear that genetically many Corded Ware were basically interchangeable with the people buried in the kurgans; some of the Corded Ware samples are actual close genetic kin to the steppe probands, second and third cousins who might even have known one another’s families by name. After 2900 BC, most of the Corded Ware also show a substantial minority (about 30%) of ancestry derived from the region’s previous occupants, the Neolithic Globular Amphorae Culture (GAC). A century later, in 2800 BC, this population moved north and west, into Scandinavia and Germany, abruptly supplanting the local Neolithic societies whose roots in the region went back millennia. After 2600 BC it was France, after 2500 BC Britain, after 2300 BC Italy and Spain. Each time, the ancient DNA record reflects an abrupt and radical shift. New pots signal new people. Because so few ancient remains have been genotyped there, the conclusions out of India are more tentative; however, the best evidence currently suggests Yamnaya ancestry appeared there after 2000 BC, as no Indian or Indian-related sample prior to that date harbors that heritage.

Since it’s no use longing to time-travel into the past, the best evidence we can hope for remains circumstantial, but it staggers the imagination how massive a demographic shift swept most of Eurasia between 3000 and 1000 BC. A small number of tribes from the bleak Pontic steppe largely replaced Northern Europe’s great megalith-building civilizations, overthrew Europe’s first literate society in Greece, the Minoans, and erased the memory of the people who had built the grand Indus Valley Civilization. The only remaining plausible candidate for who these people were is Indo-Europeans, ethnolinguistic forebears of today’s Europeans, Iranians and Indians alike.