Thanksgiving squabbles are a feature, not a bug

How eternally unsettled debates are the lifeblood of the republic

In an 1858 speech, Abraham Lincoln memorably intoned that a “house divided cannot stand,” anticipating the looming conflict when North and the South were already at odds. Though the situation in America in 2021 is obviously less dire, the timeless political divide still triggers annual familial “Civil Wars” across American dinner tables every Thanksgiving. This is such an expected part of American life that there are “explainers” for both how to debate with your uncle, and make sure you win the unavoidable arguments. To hear the media tell it, you might think these fissures are a unique feature of modern life, but vociferous politics dates back to the beginning of Western civilization, and its roots are even deeper and more universal. What’s more, these ideological divisions are a feature, not a bug.

2,100 years ago, the Roman Republic was at a crux. After centuries of conquest, internal tensions were beginning to roil the body politic, threatening to tear the republic apart from within, as poverty gripped the masses and the specter of assassination haunted the powerful. In 250 years, Rome had gone from being a central Italian city-state of 100,000 to a de facto empire of millions, stretching from Spain to Greece. Conquest was good for the aristocracy and the state they led. The wealthiest Roman families prospered from foreign plunder and the Republic gained new territories for taxation. But constant warfare immiserated the citizen-farmers who contributed the bulk of recruits to the army, taking men away from their farms for years, and driving their families into bankruptcy as their lands lay fallow.

In response to the dispossession of the Roman yeoman farmers, two brothers, Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus, proposed that indigent plebeians be given public land. This idea triggered massive resistance among the ancient land-owning nobility, and soon the Roman Senate split into two broad factions. One, the populares, favored the reforms to benefit plebeian farmers, and the other, the optimates, defended established precedent and aristocratic privileges. These two coalitions were, if you will, the liberals and conservatives of ancient Republican Rome. For their idealism, the Gracchi were both assassinated by violent mobs of optimates. Just as in the American Civil War, political passions within a republic can quickly turn deadly.

The conflict between the populares, whose faction spawned dictator Julius Caesar, and the optimates, themselves exemplified by dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla who reigned a generation before, is often contextualized within the larger drama of the demise of the late republic. Famed historical novelist Colleen McCullough expressed the widespread view that this factionalization had less to do with ideology and more with Roman dynastic power politics. But 1,900 years later, the impulses that drove some Roman Senators to support land grants to the plebeians while other patricians jealously guarded their privileged access to the public purse, were on display again in the French Assembly as 1789’s revolt against Louis XVI began. France’s Third Estate of convened lawyers, merchants and rural landowners took sides, with supporters of the king standing literally to the right of the president of the assembly, and those who opposed the king, standing on the left.

The modern origins of the terms right and left for conservative and liberal date to this period and place. But the Latin underlying the labels populares, “favoring the people,” and optimates, “the best,” highlight that left-wing populism and right-wing elitism, which would define early-modern Western political history, were already present in Republican Rome. Liberal and conservative, or progressive and reactionary, may have concrete manifestations in a particular time and place, but they reflect universal human intuitions, dispositions and preferences, unique to neither time nor place. They’re not just social and historical phenomena, but deep individual identities that develop organically out of our basic human nature.

That families argue about politics at Thanksgiving, tempers flare and nerves are often tested might be a cliché, but such conflict reflects common aspects of our humanity, which is by nature disputatious and fractious. Ultimately, there is little fundamental difference between a particularly raucous Thanksgiving shouting match and brawling in the ancient Roman forum. Each activity is politics by different means. And yet while arguments between relatives may bring discord to the dinner table, the irreconcilable differences between populares and optimates brought down the Roman Republic.

My juxtaposition of small-scale family differences of opinion with political debate around matters of state may seem strange, but sociology and history just slide on top of the roiling surface of our human psychology, which in its own turn rides atop the foundations of our biology and genetics. It would be ridiculous to say that the dictator Sulla was born to be a reactionary, just as it would be absurd to say his distant cousin and Caesar’s ally, Lucius Cornelius Cinna, was born to be a reformer. Social context matters when it comes to politics, and it is no surprise that at the Thanksgiving dinner table the biggest gaps occur between generations, moulded as they are by different circumstances. But as Aristotle long ago observed, man is a political animal and animals all have their hardwired passions. The roots of political difference and the passions they unleash ultimately lie in our genes. And they will always be with us, no matter the prevailing winds of social conditions. They are an outgrowth of our evolutionary histories, from the Roman forum to our modern dinner tables.

Politics is heritable

Though it is clear that political and tribal passions operate synergistically, in the US the cultural ethos is individualistic, and many people have personal narratives about how they arrived at their political views in a moment of awakening. Just this month, Kevin McCarthy, the Republican leader in the House of Representatives, regaled his colleagues with the tale of discovering his political identity when he was 11, watching Jimmy Carter give his malaise speech, and thinking angrily that he could only stand with a party that believed America’s best years were in the future, not the past. Hillary Clinton meanwhile credits her transformation from a conservative Barry Goldwater-supporting Republican teen to a liberal Democrat during her college years to the searing events that defined the 1960’s Civil Rights movement. In other cases, the switch was less idealistic and plainly driven by self-interest. The singer Sonny Bono got involved in Republican politics after his frustration with local government bureaucracy when attempting to open a restaurant in Palm Springs. Tulsi Gabbard’s socially conservative father, Mike, switched to the Democratic party because in Hawaii he couldn’t win office as a Republican.

From an American perspective, the common narrative here is a personal choice. Individuals in a democratic society reflect and then make their own decisions of their own free will. At least that’s the public story and what we tell ourselves about ourselves. Free will, agency and conscience reign supreme in the rhetoric of a society where politics is determined by one person having one vote. In the Platonic ideal of the American republic, citizens calmly listen and reflect upon the sage arguments of their representatives. Reality is different. Deciding whether we identify as Republican or Democrat, conservative or liberal, is filtered through our values, through our family, through our cultural milieu, and yes, through our genes. We give reason full credit for a decision that is the collective outcome of separate votes cast by cold personal self-interest, passion and social conformity, individual intuitions and hunches, and even our biological heritage.

When it comes to understanding political ideology on a personal level, 15 years ago the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt developed a “moral foundations” framework to conceptualize how liberals and conservatives evaluate different values, and how that drives their divergent political viewpoints. Haidt reports that liberals tend to emphasize “harm” and “fairness,” and put little weight on the values of “loyalty,” “authority” and “purity.” Conservatives, in contrast emphasize all five dimensions equitably. A decade earlier, in the 1990’s, cognitive linguist George Lakoff hypothesized that Republicans and conservatives followed a “strict father model” while Democrats and liberals adhered to a “nurturant parent model” (this became caricatured as the “Daddy Party” and the “Mommy Party”). But perhaps the most intuitive way to understand how politics is dependent upon other characteristics is to notice how liberalism or conservatism correlate with personality. The upshot seems to be that terms like “progressive” and “conservative” reflect a deep and simple heuristic: those on the left, liberals, and progressives, are more open to change and experimentation, and those on the right, conservatives, tend to be more rooted in custom and tradition. Conservatives conserve the old, good order, while liberals aim to create a new, better one.

In personality psychology, the dominant framework used to measure individual disposition is the “Big Five” construct. The five vectors are “agreeableness,” “openness,” “extraversion,” “conscientiousness” and “neuroticism.” Individuals who are high on openness tend to be much more liberal, and those who are high on conscientiousness are much more conservative. No matter how you decompose personality and disposition, psychologically, conservatives and liberals differ on average, and those differences drive the values which influence their political preferences. To a large extent, your vote is determined long before you watch the debate. The likelihood of your vote was determined when you were born, by the values you were raised with and reiterated as you grew into adulthood within particular social milieus, tempered by personal economic self-interests.

This isn’t surprising to anyone who has remarked on similarities between parents and offspring; personality is quite heritable. About 50% of the variation in the Big Five personality construct within the population can be accounted for by variation in genes. Because of personality’s relationship to ideological orientation, it is not surprising that political views, too, turn out to be about 50% heritable.

A common reaction to these findings is that “of course politics are heritable! Parents teach their children what views to have,” and that leads to families with a tradition of conservatism or a passion for progressive politics (or the classic cases where parental influence backfires, as epitomized in the 1980’s sitcom Family Ties, where Alex P. Keaton’s Reagan-era conservatism serves as a foil for his 1960’s hippy parents’ liberalism). But behavior genetics can separate the impacts of family environment and the genes that are transmitted from parents. Researchers have long noticed that identical twins tend to share much more in terms of their political orientation than full-siblings, despite all growing up in the same families.

In a horrific “natural experiment,” Argentina’s 1970’s right-wing military dictatorship placed the infant offspring of murdered left-wing dissidents in conservative homes. With the advent of DNA testing, many of these adopted men and women have learned their true backgrounds, and one recurrent theme is that they always knew they were different somehow. Many of these adopted children were attracted to left-wing politics as they matured, just like their biological parents had been, and in contrast to the conservatism of their adoptive parents. Their politics were as much or more a product of their biology as of their upbringing.

Today, genome-wide methods can probe political preferences down to minute molecular detail, associating segments of DNA with whether you are liberal or conservative. Political ideology turns out to be a continuous quantitative trait, like height or intelligence, with many genes controlling the variation. And like height and intelligence, it expresses itself in particular environmental contexts. In societies where individual political expression is sharply restricted, whether it be autocratic monarchies like Saudi Arabia or authoritarian Communist regimes like China, one’s ideological orientation is a moot point and may never be a live issue. Political preference as a characteristic only comes to the fore in societies where individual choices and views actually matter and are seen as a matter of civic patriotism and responsibility. Societies like the US in 2021.

The Evolutionary Context of Ideology

Like most cultural universals, say dance, religion or art, our spectrum of variation in political ideology has a deep basis in our species’ evolutionary origins. The left wing and right wing that emerged during the French Revolution over 200 years ago were the latest instances of parallel threads with prehistoric Pleistocene roots. Threads that cropped up in ancient Rome, and echo down to the present at dining tables across the country.

For an evolutionary geneticist, the very existence of variation in a characteristic with a biological basis is a sure sign of an underlying reason that that variation persists. In the human genome, the most variable sequences are found in and around regions associated with immunological response, because only human diversity can ensure our safe passage as a species through the rapidly mutating world of pathogens we inhabit. Complex organisms need to maintain a portfolio of genetic diversity, because we are always naive to the next SARS-CoV-2, and we always will be.

So what is the reason that political diversity continues to exist? There were obviously no Republican or Democrat parties 100,000 years ago. Political views, like mathematical aptitude, are extensions of innate cognitive faculties that existed in our evolutionary past and were modified in modern contexts. 50,000 years ago, the ancestors of modern humans crossed over into Sahul, the fused Pleistocene continent of New Guinea and Australia. 40,000 years ago they began pushing into areas of Siberia that Neanderthals and Denisovans had never occupied, and over 20,000 years ago modern humans migrated into the New World. 3,000 years ago Austronesian-speaking people expanded out of an ancestral homeland in the western Pacific between Taiwan and the Philippines, eventually ranging as far west as East Africa and as far east as South America. Looking at the Big Five personality construct, a minority of humans have clearly been open to migration, moving beyond their home territories, and engaging in audaciously risky enterprises. And these populations have reaped success, as their high-risk gamble paid off.

And yet for every faction that decided to take the bold, chancy step of leaving the familiarity of home, others preferred their well-known landscapes and vistas. While some humans are open to uprooting themselves, others would prefer to conscientiously heed the wisdom imparted by their elders. For those of conservative inclination, ancient rules are like gold, and novel experiences an unfathomable gamble.

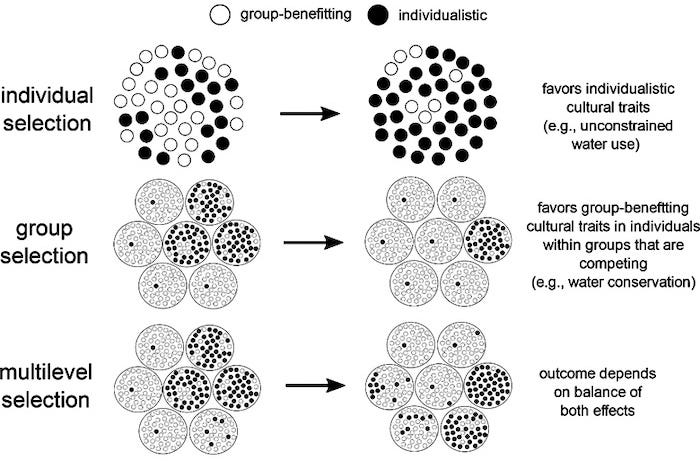

To truly understand political diversity we need to look beyond the individual-level scale and consider human groups as a whole unit as if society was a multicellular organism. Specialization within these groups is essential for social harmony, just as human tissues are cells differentiated to varied roles. A tribe where everyone preferred to be a leader rather than a follower would not function well. Similarly, one where everyone was high on openness and low on conscientiousness would likely fail at basic tasks, always seeking the novel and peculiar at the expense of the tried and tested. Usually, the best way to hunt is the way that people have always hunted, so learning from elders is critical. Inventing new methods is not only laborious, but the average outcome is likely to be inferior. Old ways are often an excellent adaptive fit to stable local ecologies. And yet a group where everyone was low on openness and very conscientious in adhering to custom and tradition would miss new opportunities. The potato was cultivated in Russia only after 1850, due to resistance from conservative peasants, despite the fact Russian agronomists had long seen the opportunity that the potato presented, leading Catherine the Great to promote its cultivation a century earlier. But the conservative serfs balked, delaying the development of classic Russian potato dishes by more than a century, and likely suffering famines needlessly.

In contrast to Russia, in Ireland the peasants adopted the potato with gusto, making it the staple crop by 1810. Due to the potato’s productivity in poor soils, Ireland underwent a population explosion, with a 19th-century population peak only finally matched again in 2021. Of course, the denouement of the potato’s exclusive popularity in Ireland was the famine that brought the death and migration of millions. Irish openness to the new was too enthusiastic, and when disease struck, they were over-reliant on a single crop. Sometimes old traditions and customs make you robust to the vicissitudes and enthusiasms of the present, something the Irish learned firsthand.

And yet these differences, with consequences that are often amazing and tragic in turns, are the raw material of human evolution. Our ability to adapt as societies rely on individual variation so that not everyone is always on the same page. In early 2020, “COVID-19 hawks” were a helter-skelter band of heterodox heretics, left-wing, right-wing, but all united in their suspicion of authority (Dr. Anthony Fauci was denying that COVID-19 was anything to worry about in late January 2020). But thinking outside the box is not always beneficial, and COVID-19 was preceded by H1N1, where it turned out that the worrywarts were wrong, and business as usual was for the best.

Human faction will be eternal

Rather than an eternal cycle of rise and fall, the American mind is conditioned to expect linear progress. To all arguments, there is a resolution after a full-throated debate. A finality of disputes adjudicated by truth. Americans see a future where their ideological enemies will be banished to the dustbin of history, where radical energies that were unleashed with Communism are extinguished once and for all, or the reactionary reflex is destined to become taboo as we attain a liberal democratic “end of history.” But this presumes that political ideology and passions are purely social and historical phenomena, to be neatly engineered and argued away with the passage of time and the expenditure of effort.

The sort of debate that reverberates through the halls of Congress and brings discord to holiday dinner tables isn’t historically contingent, it’s a fact of our universe. Left and right are two wings of human nature, and our species’ successful explosion over the last 100,000 years across the six continents derives from the flexibility that variability in human nature enables. Human ingenuity is the outcome of the great debates we’ve had for hundreds of thousands of years. We are a species capable of crossing vast oceans fueled by hope and audacity, even in the face of the longest odds. But our spirit is not entirely restless, and even to this day, human societies arrange themselves around ideas with roots in the Late Bronze Age. Edward Gibbon observed in the 18th century that the Roman Catholic Church was the “ghost of the Roman Empire,” and 250 years later that ghost has certainly not faded.

McCullough made of the ideological factions of the late Roman Republic masks for her dramatis personae’s ambitions in her Masters of Rome series. This was certainly smart from the perspective of a novelist more focused on the personal life of the arch-conservative Cato the Younger than his ponderous political exhortations. But every age bears witness to the common textures of human nature that make us who we are as individuals, and shape the variety and flexibility of human culture, from the factious Romans down to the “Red America” and “Blue America” of 2021. The fundamental tensions that set Sulla, who wished to make the Republic as great as it had been in the past, against Caesar, who imagined a different and glorious future, remain with us 2,000 years later. You might lament the strife and conflict on the pages of a newspaper, filling your news feed, blaring from a screen, or erupting at your holiday dining table. I take the long view. I see the glorious birthright of a species evolved to endure, the impulses of its eternal extremists be damned.

Hi, Razib, look at you as I look at me, and what do we see? Two guys not simply minded, not only this, not only that. The dialectics in age, work and progress want to be be observed.

Absolutely fantastic writing, I loved it!