RKUL: Time Well Spent 07/07/2023

Summer roadtrip edition

Your time is finite. Your phone and the internet stand ready to help you squander it. Here are my latest picks for spending it well instead. Feel free to add more in the comments.

Books, what else?

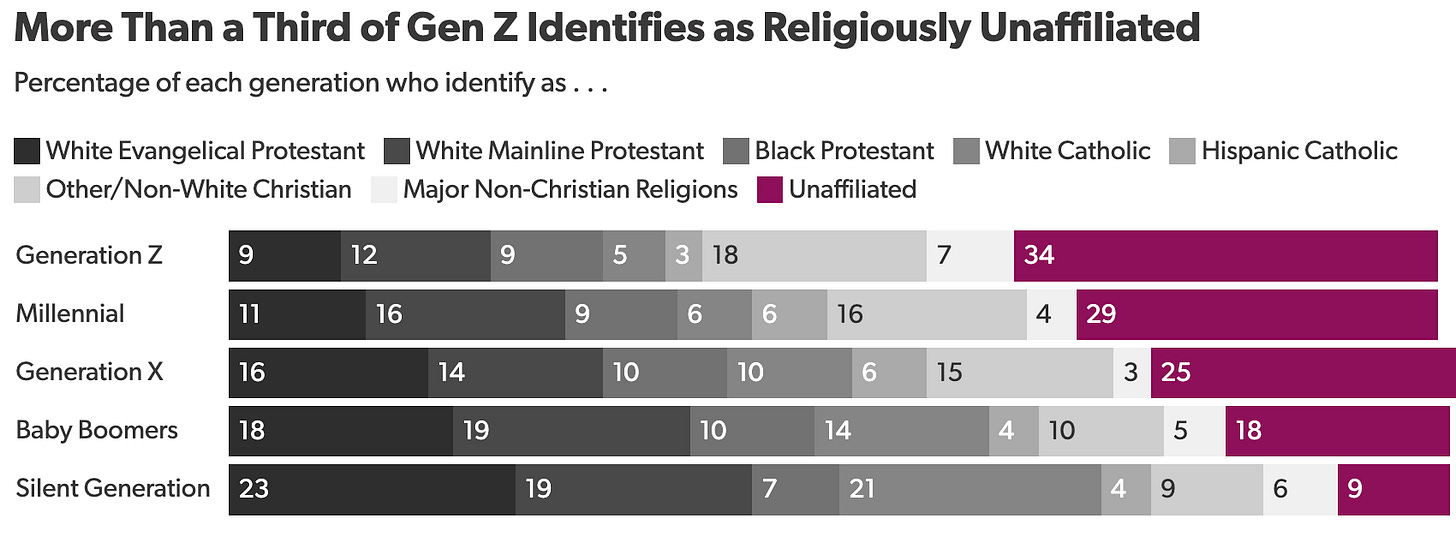

This week on the Unsupervised Learning I recorded a podcast with Lyman Stone about the decline of religion in America over the last 25 years. We live in an age of change, and a normatively Christian America is now transitioning to becoming a post-Christian America. Many Americans do not know how to deal with this new situation, and as someone who grew up in the last decades of the 20th century, I can tell you it strikes me as strange as well. For most of the history of the American Republic, you were Christian, or Christianity was the religion you were not. But the figure below shows the trajectory of American religion into the near future:

In youth, a person establishes the contours of their religious life. By the middle of the 21st century, the generation becoming dominant in American life will be over 40% non-Christian.

Of course, this is not the first time a culture and nation have changed religious orientation in a few generations. Edward J. Watts’ The Final Pagan Generation: Rome's Unexpected Path to Christianity is one of the best treatments of the 4th-century religious and cultural transition in the Classical World. But there are many other instances of this phenomenon.

Michelle Salzman’s The Making of a Christian Aristocracy: Social and Religious Change in the Western Roman Empire and Rodney Stark’s The Rise of Christianity approach the same question differently. Salzman is an academic historian, and her work traces the gradual evolution of the Roman senatorial elite’s views and affiliations, from being almost entirely pagan in 300 AD to substantially Christian by 400 AD. She traces genealogies and biographies to address hypotheses about Christianization that scholars have mooted since Edward Gibbon's The Decline and Fall of the Rome Empire was published in the 18th century. For example, The Making of a Christian Aristocracy finds that women were not catalysts for religious conversion, as argued by Ross Kraemer in Women's Religions in the Greco-Roman World. Unsurprisingly, Salzman reports that the nobles Constantine promoted were those whose families were more likely to become Christian, while those with more ancient and storied lineages, less reliant on imperial patronage, persisted in their paganism. She prefigures theoretical models of cultural evolution by Peter Turchin (most recently the author of End Times: Elites, Counter-Elites, and the Path of Political Disintegration), showing that conversion occurred faster along the imperial frontiers, as opposed to in the old Roman core.

In contrast, Stark’s The Rise of Christianity is more sociological than historical, focusing on fitting the data to explicit exponential growth models. His overarching conclusion is that Christianity grew in the Roman Empire gradually via autocatalytic bottom-up conversion among urban elites and sub-elites. The patronage of the first Christian emperor, Constantine the Great, wasn’t really important in the long run. Stark also infers that the new religion's core early demographic base were Hellenistic Jews because of the strong correlation between early centers of Christianity and areas of high Jewish concentration. While Salzman’s work focuses on elite dynamics, Stark presents a general theoretical framework for social change through individual choice and preference.

Richard Fletcher’s The Barbarian Conversion: From Paganism to Christianity shifts the focus to Northern Europe, where the dynamics of religious change were radically different from Rome. When Constantine began to favor Christianity in the early 4th century, the religion had already been widely practiced for more than a century. It was initially seen as alien to Classical society, but over time it became part and parcel of Roman culture. In most of Northern Europe on the other hand, Christianity spread not through conversion of the masses (Ireland being the exception), but via royal fiat. The Barbarian Conversion documents this haphazard process, where kings sometimes continued to worship the old gods alongside the new. Though Northern and Southern Europe are Christian, they arrived at the religion’s dominance through radically different processes. Rome’s adoption of Christianity was the institutionalization of something that had already become substantially indigenized; Northern Europe’s adoption of Christianity was its integration into a Roman-centered early medieval culture.

Jumping forward to the late 20th and early 21st century, Philip Jenkins's The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity documents Christianity’s demographic transformation, in particular the rise of Africa. Jenkins, author of many books on Christian history, argues that this century will be as pivotal as the period after Islamic conquests in the 7th century, when Christianity shifted from being a Near Eastern religion to a European one. The Next Christendom was originally published in 2002, but it anticipated the reality that in the 2020’s a greater number of Christians live in Africa than in Europe, and that the future of the religion’s theological direction and institutional heft will be shifted southward simply through sheer force of numbers. Even in European capitals, some of the most vigorous Christian congregations consist of African immigrants, rather than natives.

Victor Lieberman’s Strange Parallels: Integration on the Mainland: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c.800–1830 is the first book in a duology that articulates a thesis about the relationship between geography and political development in Eurasia. While the second book focuses on numerous Eurasian societies, the first volume looks at the deep roots of Burma, Thailand and Vietnam (and to a lesser extent Cambodia). Lieberman’s thesis is geographical, that the sheltered location of early Southeast Asian polities allowed them to develop more organically than China and India to their north and west, respectively. But Strange Parallels also probes the ideological differences between the more Indic societies of the West and the Sinic orientation of the Vietnamese nation-state in the east. Lieberman outlines the ideology of “solar polities” that emerged in Thailand, Burma and Cambodia, where elite religious ideologies bound a society to a king, but imposed minimal demands on peasants. In contrast, Vietnam adopted a Chinese model of rule by scholar-officials that required broader investment in education, and marginalized previously influential religious institutions like the Buddhist Sangha.

While Theravada Buddhism was becoming the dominant religion of Southeast Asia in the early second millennium, in India the religion went into sharp decline during the same period. In its place emerged a strange coexistence between a majority Hindu population, practicing indigenous traditions, and intrusive Muslims from Central and West Asia who converted large swaths of the native peoples. Great numbers of Muslims in northwest India are understandable in light of the region’s proximity to the Dar-al-Islam, but a curious fact is that numerically, South-Asian Islamic resurges in the far east, in Bengal. Richard Eaton’s The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204-1760 attempts to address this conundrum. Eaton, a Persianist, observes that much of the eastern part of Bengal, now Bangladesh, was not settled until after the Muslims ascent in the subcontinent in the 13th century. Because the sponsors of the settlement were Muslim elites, the local peasants adopted the Islamic religion of their rulers. He notes that the Portuguese noted the dominance of Islam among the peasantry as early as the 16th century. Again, this pattern is in keeping with Turchin’s thesis that marchlands and border zones tend to adopt and promote newer ideologies faster and more thoroughly than the civilizational cores.

Thought

India’s Population Surpasses China’s, Shifting the World’s ‘Center of Gravity’ - The new global order reflects deep changes in both countries, with economic and geopolitical consequences. This isn’t a big deal, just a statistic where India finally surpassed China. But it’s a good signpost to start talking about geopolitical rebalancing as the “Age of Asia” shifts its weight and character. India is a relative lightweight economically compared to China, but because of its large numbers of English speakers, it will arguably be much more impactful culturally.

The Mystery of the Stonehenge "Amesbury Archer”. If you haven’t subscribed to Dan Davis’ YouTube channel, I highly recommend it! Davis combines archaeology, anthropology and genetics in his videos, highlighting topics of interest in European history. In this video, he discusses high-status individuals who were buried around the site of Stonehenge.

The Ideological Subversion of Biology. This article in Skeptical Inquirer was written by Jerry. Coyne and Luana Maroja. Most readers will know Coyne from his excellent site Why Evolution is True, but over the last few years, he has been speaking out about the influence of politics within biology. If you are not a biologist, it might be an eye-opening read about where biology has gone in the last few years.

The illusion of moral decline. This post is a distillation of a paper written by Adam Mastroianni, of the same title in Nature. Mastroianni argues that everyone everywhere thinks the past was more morally upright. I definitely think the past was more morally upright, so I guess this is a case where I’ve gotten caught in this cognitive and cultural illusion.

Harvard Professor Under Scrutiny for Alleged Data Fraud. This individual is a massively cited academic. Incidents like this are one reason many people don’t care anymore when you say “studies say.” Of note incidentally, the alleged fraudster’s book entitled Rebel Talent: Why It Pays to Break the Rules at Work and in Life.

Data

The life history of human foraging: Cross-cultural and individual variation. This is the biggest survey of hunter-gatherers published so far, with 23,000 hunting records from 1800 individuals at 40 locations. The authors found that skill peaked between 30 and 35, only gradually declining. This suggests that naive models whereby prehistoric humans were viewed as senior citizens by their 30’s are unfounded.

Ancient DNA reveals the origins of the Albanians. Nothing too surprising, but interesting to note proto-Albanian steppe ancestry seems to come from relatively pure Yamnaya populations, rather than Corded Ware groups who carried about 25% Neolithic Globular Amphora ancestry and were the antecedents of the vast majority of European Indo-European groups (Germanic, Celtic, Italic, Baltic and Slavic). The basic ancestral mix was later supplemented by substantial Slavic ancestry, though the ancient Illyrian paternal lineages were maintained in the region.

South Asian medical cohorts reveal strong founder effects and high rates of homozygosity. Studies of conditions like heart disease or lung cancer routinely group probands by background, revealing lots of inbreeding, in particular in the Pakistani samples. This drives a lot of recessive diseases in South Asian cohorts in the West.

Large-scale phylogenomics uncovers a complex evolutionary history and extensive ancestral gene flow in an African primate radiation. A group of 22 Old World primate species that engage in extensive hybridization, probably like our own lineage until recently.

Genetic similarity between relatives provides evidence on the presence and history of assortative mating. A new preprint that quantifies the correlation within families of particular traits. Basically, humans pair up based on traits, and this research group used an extensive Norwegian dataset to measure the magnitude of sorting by characteristic.

My Two Cents

There’s still no free lunch, free subscribers; my most in-depth pieces for this Substack remain beyond the paywall. Since the last “Time Well Spent” I’ve released two longer pieces.

You’re so Turk and you don’t even know it:

When Turks arrived in the civilized world, they took power by force, but they did not, decisively, usher in an age of barbarism or decline, razing their predecessors’ monuments or gutting their institutions. Justinian the Great’s Hagia Sophia became a mosque and Ottoman Istanbul remained as culturally refined as the Byzantine Constantinople it succeeded. In Central Asia, descendants of the bloodthirsty Turkic warlord Timur were known for their generous patronage of literature and astronomy, while in the Indian subcontinent, these Timurids fostered Islamicate Persian poetry’s flowering. The Turks came from the barren north, and rose from the slave soldiers’ barracks, but their millennium of dominion over Eurasia did not end civilization. It reinforced and extended it, an astute approach that bought the Turks unrivaled, if little recognized, longevity.

Our explosive past: on cataclysms and demographics:

74,000 years ago, a volcano erupted at western Indonesia’s Lake Toba, leaving half a foot of ashfall as far west as India. The most powerful explosion of the last 2.5 million years, the Toba eruption triggered a decade-long cold snap that wrought havoc even amid the last Ice Age’s already inclement conditions. When the cataclysm hit, Neanderthals had reigned supreme from the Atlantic to the Siberian Altai for hundreds of thousands of years, while their Denisovan cousins dominated East Asia. To the south, diminutive small-brained human populations occupied Indonesia’s Flores islands and Luzon in the Philippines, coexisting with both modern humans and Denisovans. But thirty thousand years after Toba, a blink of the eye in geological time, the landscape of human geography was abruptly transformed. Neanderthals, Denisovans and Southeast Asia’s enigmatic hominins were extinct or under extreme, terminal pressure from African newcomers. Neanderthals, by then resident in Europe for over 500,000 years, disappeared 5,000 years after that mass arrival of African humans to northwest Eurasia. Denisovans, by then as far into their East Asian sojourn as Neanderthals their western one, disappeared soon after their cousins. Finally, the small human populations of Flores and the Philippines also died out 50,000 years ago, after modern humans’ final expansion. This radical homogenization of Eurasian humanity is associated with the expansion of the Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP) archaeological culture, which radiated out of the Middle East 50,000 years ago, washing over the whole of Asia, Europe and Australia by 45,000 years ago.

If you want to browse my more geographically focused pieces, Dry.io has created an interactive map of them. We’ll keep adding to that page over time. Also, Dry.io set up a nice skin for my pinboard bookmarks and a page for reader-submitted links.

Discussion

All my podcasts go ungated two weeks after their Substack release. So I encourage subscribers on the free plan who’d like to automatically get them to subscribe to that podcast stream (Apple, Stitcher, and Spotify). If you want to listen on YouTube, please subscribe.

Here are my guests (and monologue topics) since the last Time Well Spent:

The out-of-Africa event in the light of ancient DNA and genomics

And here are the currently ungated podcasts all in one place.

For subscribers, I post transcripts (automatically generated, though I have someone going through to catch major errors).

ICYMI

Some of you follow me on my newsletter or Twitter. But my own domain also has all of the links and updates: https://www.razib.com. There you’ll find links to the few different podcasts I’ve contributed to or run, my total RSS feed, links to more mainstream or print articles when I remember to post them, my Twitter, the occasional guest appearance here and there, etc.

Email me

My total feed of content

Some of my past pieces for UnHerd, National Review, The Manhattan Institute, Quillette, and The New York Times

Over to you

Comments are open to all for this post, so if you have more reading/listening suggestions or tips on who I should be talking to or what you hope I’ll write about, lay it on us.

Are you going to write about Gregory Clark's new paper, "The inheritance of social status: England, 1600 to 2022"?

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2300926120

Or maybe you already have and I missed it

Anyways I would be interested to read your take on it if it were a Substack article. The paper seems to be a huuuuge splash in the geneology world, on twitter at least, and I am not really sure what to make of it

I am sure it would get a ton of clicks if you did a deep dive into it

Every older generation sees moral "decline" in the young ones. But is is not a decline, it is a shift to a different set of morals. I for one am happy that burning elderly women at the stake is no longer acceptable, that women are allowed education, are also allowed to take a job (not H-4's of course) and that they have the right to reproductive freedom. Oh wait - some people that could not see the difference between declining and shifting set the clock back in this regard ! SCOTUS also opened the door to a return to discrimination by allowing a woman who apparently never created a website the right to refuse people her creative coding services. Not because they are NaZi's but because they love one another. Then we discover the couple mentioned in this case does not exist.

So maybe I agree that there is moral decline happening in the US. Not amongst the younger generation, but amongst the older one, on the highest levels.