Thanks for subscribing to Razib Khan’s Unsupervised Learning. The month of May brought paid subscribers a big stack of reading. Here’s a sampler of the five deep-dive pieces that went up behind the paywall in recent weeks. Subscribers who’ve already read them will find some follow-up notes throughout.

Outcast as I wanna be, parts 1 and 2

This week I released a two-part series on the startling resilience of Romani populations, looking into the genetics of the group and the cultural choices that have assured their survival. Part one begins:

Join me in a Clubhouse room or catch me on a podcast and there’s no disguising it: I am a very American guy. But browse my genetic results and there is only one possible, entirely unrelated interpretation: these genes are 100% Bengali and can be pinpointed to my parents’ precise ancestral districts. The culture I embrace and the genes I carry sharply diverged almost four decades ago when I set foot in an American kindergarten. My half-Bengali kids’ genetic profile might be more exotic, but culturally there aren’t even any paths diverging in the woods for them. Their culture and their accents are both “broadly American” and the fact of their genetic partial “Indian-ness” comes up at most as a detail on demographic sections of forms.

But both culture and biology drive human evolution. In my case, any loyalty I have is to the broader culture that shaped me, not to the accident of my ancestry. I am wholly assimilated into a culture where I’m a genetic minority. And odds are that the ever shorter threads of my DNA that wend their way into the future, generation over generation, will do so alongside novel alliances of genes that resemble my complement less and less with every recombination event. In the long run, my specific genetic disappearing act isn’t really much faster than anyone else’s.

But what if instead, I had wanted to keep to my parents’ culture and my genetic kind? What if I were among a group of South Asian migrants who wanted to remain culturally apart, an island standing aloof in the sea of European culture and genetics? How long could we last? What would be our key strategies to avoid being absorbed?

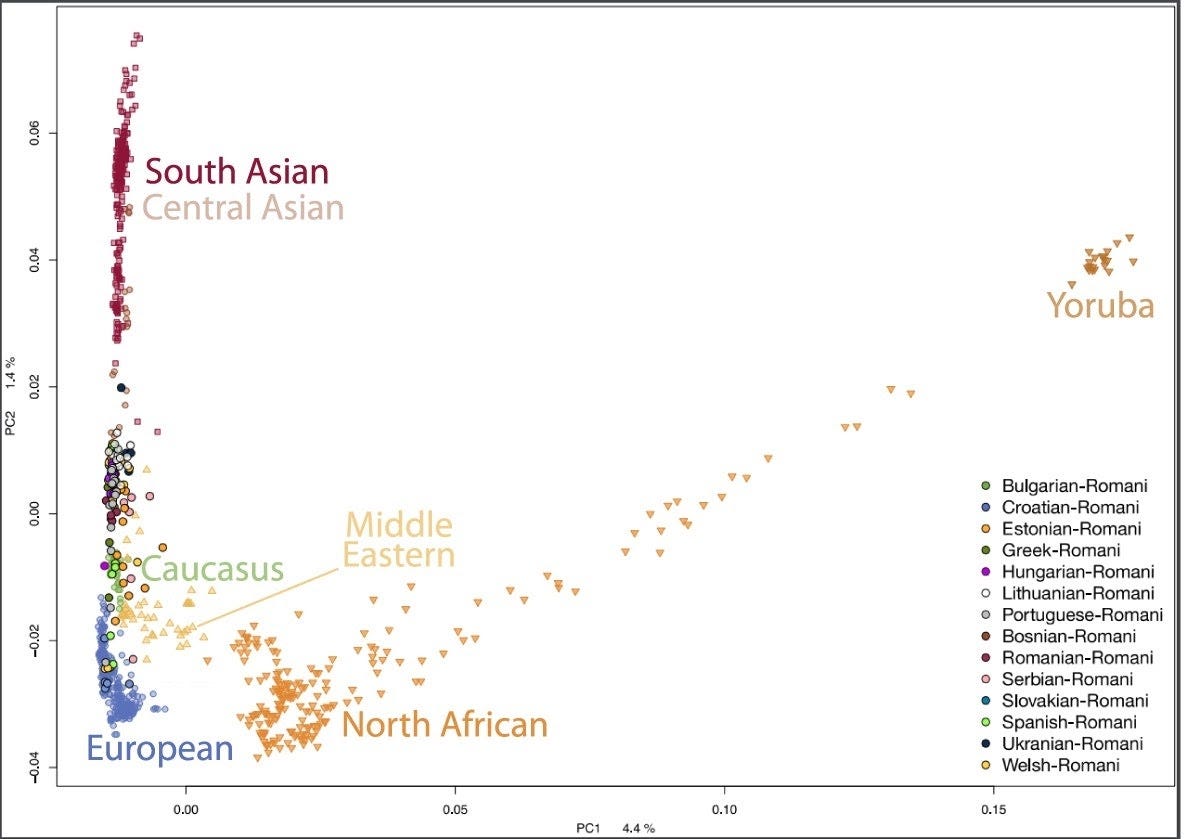

Well, history has been running this experiment for around a millennium. Across Europe, a set of societies remain apart, still instantly recognizable 1,000 years on, both culturally and genetically. Across Europe, today they answer to various local names, including Roma, Romanichal, Kale, Gypsy and Gitano, but are broadly called Romani. Most of their ancestry is European, but the defining elements of their culture bear all the hallmarks of their distant Indian origins. Their language, religion, and social customs all have a clear basis in subcontinental societies, despite centuries of mixing with others. The Romani language is Indo-Aryan, the Romani word for the Christian cross is the term for the Hindu god Shiva’s trident, and their interaction with outsiders is marked by casteist segregation and taboos on pollution. Though radically transformed, the South-Asian basis of their culture is clear to anyone who chooses to look. They are a classic illustration of disparate forces of evolution at work.

In the rest of the piece, I take you through what genetics today can tell us about how long the Romani have been in Europe, how they might have arrived and how much they mixed with their suspicious, and often vengeful neighbors over the centuries. Spoiler: a lot, and most of it neatly accords with what historical linguistics has posited for decades.

In part two, I go deeper into what they have endured in their home of the last millennium and how they’ve thrived in spite of it.

Though the surrounding cultures that the Romani have lived among have persecuted them, even enslaved them, the reality is that the Romani themselves take a very dim view of outsiders. They exist in the world of the gadje, but they are not of it. In the 11th century, the Islamic scholar Al-Biruni wrote the first outsider’s anthropology of the Indian subcontinent, and observed that Hindus express little curiosity about the history and religion of foreigners. He states that “The Hindus believe that there is no country but theirs, no nation like theirs, no king like theirs, no religion like theirs, no science like theirs.” He contended that Indians were totally inward-looking. This orientation may actually have held the Romani in good stead in the outside world.

Over to you

After the post, I heard from a reader with recent Romanichal in his pedigree. If anyone else with Romani, Romanichal etc. ancestry has DTC genetic results they’d like my take on, feel free to respond to this email (razib@substack.com). I am always happy either to just take a look privately or a share a handful of anonymized results in some format for readers’ edification if I get multiple readers who’d like to share.

All matters steppe: pod to post

I’m slowly working my way through that long-term series of pieces on the steppe. All subscribers in April already received my reading recommendations and an introduction to the project, Entering Steppelandia. This month, I got out three long pieces on the Yamnaya era of steppe expansion. Meanwhile, many of my recent podcasts have been with the researchers behind the books I recommend about the field.

Thomas Olander: the origin and spread of Indo-European languages

Here are the currently ungated podcasts

The discussion with Favereau is the odd one out in terms of era, but I was excited to talk to her after reviewing her new book for UnHerd, What the Mongols did for us: The Golden Horde wasn't barbarous, it created the modern world. Try writing something that gets titled like that, and having the surname “Khan,” with the comments open. I have known for a decade that I am not, alas, a carrier of Genghis Khan’s paternal lineage, but that is another matter for another, future steppe post.

The conversations with Anthony, Kristiansen and Mallory were even more connected than they seem. All archaeologists, their scholarly lives have been intertwined for decades. In 2015, Anthony was an author on a paper: Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe, while Kristiansen co-authored Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. These two publications were very similar, and established the same conclusion: there was a massive migration from the steppe into Europe 5,000 years ago. Mallory happened to be a reviewer on both of these publications.

Thomas Olander is a younger Danish scholar who is exploring the topics of concern to Anthony, Kristiansen, and Mallory, but while they are archaeologists he is a historical linguist. My discussion with him exposes the cutting edge of what we know about the relationship of the various branches of the Indo-European languages. Olander and his colleagues use techniques of phylogenetics pioneered in biology.

And lest you fear I won’t stop until I interview every steppe-ist, let me reassure you that among the podcasts up next are conversations with biologists, futurists, commentators and cultural figures.

Some of the steppe preoccupations I’m working through next are their evolutionary adaptations, linguistic paleontology, and their tradition of young “wolf warriors.” I’ll be looking at the roots of lactose tolerance, the plague and the Spartan agoge in Yamnaya culture.

Steppe 1.0, Going Nomad

We have no written testimony of this scarcely human phenomenon steamrolling the settlements of stolid farmers whose ancestors had tilled the land for millennia. The nomads’ inexorable progress onward, onward, outward in concentric arcs, mowing down or swallowing up all who stood in their way, was marked by neither enduring architectural monuments nor ambitious infrastructure projects like Rome left those they subjugated. They came, they took, they surely slaughtered, and they clearly fathered. But with neither written words, nor enduring walls, how do we know them?

Like a black hole, they warped even the distant future of every adjacent nation they touched. And so, like astrophysicists studying a black hole, we grope our way to a picture of the prehistoric Indo-European nomads, not directly, but through the vast arc of Eurasian geography that curls around the windswept steppe to its west, south and east. These barbarian, nomadic Indo-Europeans gave rise to civilized, urban Indo-European societies as far apart as Italy, Iran, and India. The history, culture, mythology and linguistic patrimony of most of Eurasia, particularly its most dominant empires, bear unmistakable if begrudging testimony to violent brushes with the nomad peoples of the steppe.

And, of course, a focus on humans alone will only take you so far in this story:

To understand the Yamnaya miracle, it pays to look beyond our own species. Nomadism opened up enormous opportunities, but to capitalize on them, the Yamnaya needed to strike fast. As if they had arrived on winged horses.

Steppe 1.1a: A nowhere man's world

For 2,500 years, these first European farmers had dominated the continent, a stretch as long as between the Greek victory at Marathon and today. Great civilizations rose, the megaliths that still litter Europe’s Atlantic coast the fruits of their organization and ambition. But then 5,000 years ago, in the space of just a few human lifetimes, it all ended. The age of the megalith gave way to one of wagons.

The Yamnaya were many things, but rigid was not one of them. Unlike their nomadic successors, they were not content to simply harry the settled lands around the fringe of the steppe, to plunder and retreat back to their grand tents. They invaded rich lands beyond the steppe, swallowed them whole, and in the process underwent additional transformations of their own. The story of the Yamnaya is the story of cultural shapeshifters, who nevertheless maintained a strong link with their past, their myths and their language.

Steppe 1.1b: culture vultures descend

But we do not know the stories of the Varna. All that remains of them is the bright, cold metal they forged. They were laid to rest dripping in gold, the blinged-out cadavers of a cultural dead end. Far to the northeast, huddled in the valleys of the Pontic steppe, the ancestors of the Yamnaya scratched out a marginal existence on the edge of the agricultural world. Their victories were counted in years of survival, a bit of bland pottage and pork, not glittering gold. But the future would be theirs. Facing meager harvests, perhaps the Yamnaya did not fear the life of the open plains, and eagerly grasped the opportunity offered by the wheel and the wagon, turning their backs on ancestral traditions and embracing the new. Their choice may have been born of desperation and poverty, but their reward was increase and conquest beyond their wildest dreams.

You make me want to read

Behind the paywall, I appreciate all the comments on each post, yes even Milan T.’s treatises. But it’s particularly nice when someone takes the time to reach out with an email. Here are a couple lines from notes I especially appreciated after one of the steppe installments.

From M.: . . . and your topics provide a welcome diversion to that stuff. My undergraduate degree was in history, but I concentrated, if one can say that, in world history. I read, for example, one of Gordon Childe's books. Your work has rekindled my interest.

And from R.: Thank you for sharing this Steppe history. It’s absolutely riveting and so fascinating. I’ve re-read David Reich’s book which, thanks to your Substack and podcasts, has become a much less impenetrable read.

And that is my kind of praise. Thanks, guys!

I’ve just seen your digression on MT’s comments. Well, all my comments are made in a good faith and supported by evidence. They always use the logic or imply the lack of in other comments and podcasts. I think, the best contribution is to have a critical perspective. The truth is that I do not like a groupthink and maybe do not give much credits on assertions I agree with. Some people complained against some of my assertions but when the time came to put facts on the table they disappeared. I will not apologize if I know some things better than some people. .

Some others (on OT for example) do not like to hear some historical things although they know that they are truthful. So far, I experienced that the following groups tried to ban me – jihadists, oit lunatics (only because I asserted that Aryans came from outside not originated in today’s India although, this was also asserted by Razib and majority of BP readers) and the latest is the one who cannot handle the truth about US/West imperial politics. I do challenge anyone to come and discuss sc. ‘Indo-Europeans’ and their language or anything else.

Just to note that couple years ago I wrote about the genocide conducted by Yamnaya on European indigenous people and abduction of their women (none believed me) and we now got confirmation by KK in his podcast that this really happened. Some readers are maybe agitated by the fact that they are actually descendants of these ‘monsters’ with stone maces and abducted raped Vinca women. I don’t know if someone in the world discussed this detail before, but I am sure that it will be more discussions about this and its psychological reflections on modern generations.

Finally, I do expect that, at the end of the IE serial, you will accept my suggestion to propose the abandoning of the meaningless term ‘Indo-European’ people/language and use simple – Yamnaya language. Cheers!

I have listened all podcasts but, it seems, I was not sufficiently focussed and missed couple things. I would ask a better focussed listener to save my time to re-listen podcasts again and explain me:

- If Yamnaya nomads were actual Aryans who came to today’s India?

- If Yamnaya ‘Indo-European’ language is actually a language which localized version was Sanskrit?

- Were Rg Veda and accompanied mythology a Yamnaya creation?

Thanks.