RKUL: a little light reading, June-July 2021

a sampler of recent paid posts (with follow-up notes)

Thanks for subscribing to Razib Khan’s Unsupervised Learning. June and July brought paid subscribers a big stack of reading. Here’s a sampler of the six deep-dive pieces that went up behind the paywall this summer. Subscribers who’ve already read them will find some follow-up notes throughout.

Duke Tales: I see Finland in the strangest places (part 1)

I kicked off the six-part series on Finnish genetic history and culture with a free piece that’s a bit of a departure. In it, I reflect on the strange reversals in my neighborhood during the Texas blizzard of 2021, and how they put me in mind of the unique adaptability of Finns:

Europe is also Finland, a beautifully remote and marginal land raked with thousands of lakes. It can be about as accommodating as a winter week during a global pandemic, overlaid with a freak ice storm, no snow plows, a collapsed electrical grid and commerce and transport grinding to a halt. Finland, in other words, has not always been ideal for the equivalent of the Tech Bros and me. Certainly in the past, our counterparts who might have been doing very nicely for themselves in the knowledge centers of the heart of Europe would have been the first to be culled by what mother nature continually meted out to her hardy Finnish subjects.

Weirdness as a national pastime (part 2)

In the second piece, I dig into the cultural and historical peculiarities of the Finns, who speak a non-Indo-European language, and exhibit slight, but long remarked-on physical differences from other Europeans. I also put a spotlight on the strange Nazi obsession with the Finns and the Baltic peoples more generally:

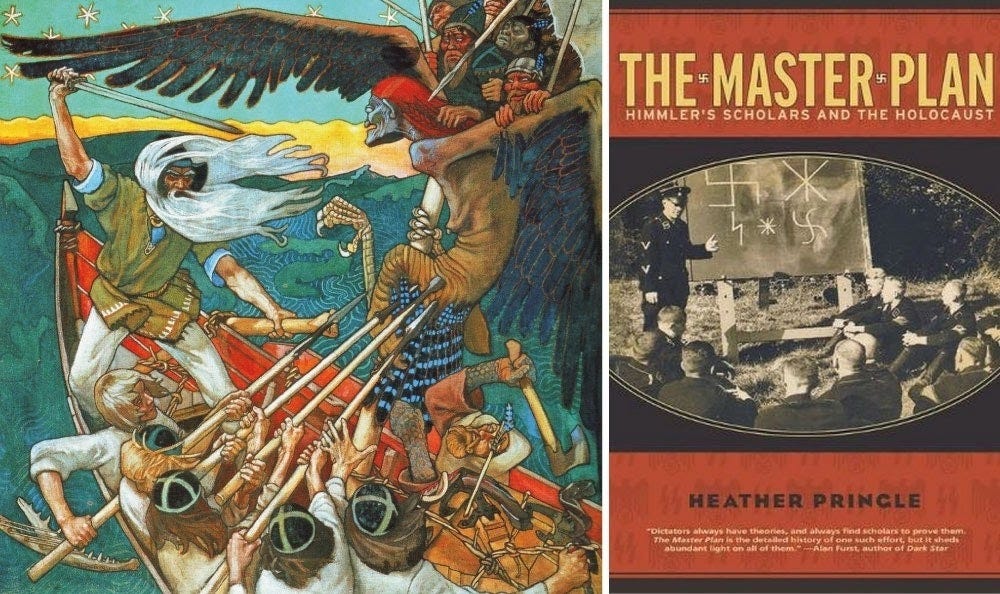

One German friend told me everyone knew the Finns are “strange,” with a sullen affect and propensity for dark moods. That made me think of Heather Pringle’s The Master Plan: Himmler's Scholars and the Holocaust and its references to Finland. Apparently, Himmler, the head of the SS, believed in the occult and sent ethnographers and archaeologists to Finland and the neighboring region of Karelia to conduct excavations and study the folklore. They recorded songs for future use that were purported to encode magical powers once wielded by the wizard Väinämöinen. Himmler’s bizarre faith in magic might seem silly (it did to Hilter, who expressed personal contempt and embarrassment for his subordinate’s enthusiasms and tried to deny him funding, which Himmler then just gathered behind Hitler’s back), but it was true that the folk shamans of Finland continued to live in an enchanted world dominated by strange spirits and unseen powers long since faded from memory in the rest of Europe.

Go west, young Siberian (part 3)

Getting into the genetics, one notable and clear aspect of Finnish variation is that their distinctiveness comes in through the paternal lineage. Men only. While the maternal lineages of Finns resemble Swedes, their paternal lineages are totally different. Finnish paternal lineages are turning up in places I think none of us imagines:

And the descendants of these men can be found in peculiar and surprisingly high places. In the 9th century AD, a Swedish prince named Rurik built a fortification north of modern-day St. Petersburg. Rurik was a Varangian, one of the eastern Vikings journeying out of Sweden into the vast lands west of the Urals occupied by pagan Slav tribes. Varangians famously served as bodyguards for the Byzantine Emperor, far to the south. Like these adventurers, Rurik’s son was drawn by the wealth of the south, and captured the city of Kiev, in what is modern-day Ukraine. His descendants would go on to become the direct paternal ancestors of all Russian rulers from the 10th century AD until 1598 (when the Romanovs came to power).

From deepest Siberia to Europe’s edge (part 4)

Delving deeper into the genetics of Finns, and looking at their whole genome, it seems clear from ancient DNA that the modern Finns derive from a Siberian people:

Ancient DNA and genomics have now brought the story nearly into focus. As we assimilate each new discovery into our body of knowledge, the only remaining viable theory is that the genetic uniqueness of the Finnic people is a product of relatively recent history, not a feature of deep time. Before 500 BC, the languages spoken in the coastal East Baltic were likely related to forerunners of modern Scandinavian or Slavic languages, not Finnish or Estonian, a tentative conclusion we can hazard with quite strong confidence based on genetic remains from the period. These populations had no Siberian ancestry. The populations’ genetic profile and material culture were exactly the same as contemporaneous populations in Bronze-Age Sweden. Earlier hunter-gatherer populations among whom we once hunted for traces of special Siberian ancestry, like the CCC [Comb Ceramic Culture], that had long resided in Scandinavia and Finland, had already been mostly absorbed by these Indo-Europeans by the time the eastern ancestors of the Finns made their entrance.

Frontier Finns: cabins, rakes & Indians (part 5)

Though Finns are connected to deep Siberia, in the fifth piece I wanted to dig into their impact on America. Early Finns pioneered the log cabin in Delaware, but even today there are parts of America where they are an essential part of the cultural stew:

Though the early Finns of New Sweden were influential, they are not the most numerous of America’s Finns, as they never numbered more than a few thousand. In the decades around 1900, hundreds of thousands of Finns migrated to the United States. Perhaps more than ten percent of Finland’s population at the time. The largest proportion settled in the Upper Midwest, just like their Scandinavian neighbors. The northern fringe of Minnesota and Wisconsin, and the upper peninsula of Michigan, are home to many Finnish Americans, as well as the Ojibwe Native American nation. Just as was the case in early Delaware, the outdoors-oriented Finns easily mixed with the native peoples, giving rise to a subculture of “Finndians” (video), who synthesize the customs and traditions of the Old and New World “birch-tree-belt.” Hunting, fishing and a sauna/sweat-lodge culture allow these people with their northern roots to meet on common and mutual ground in a way that might be less plausible if the European immigrants had been from the olive groves of the Mediterranean.

Finnish brains, baiting and bottlenecks (part 6)

Finally, in part six I conclude with a piece on Finnish uniqueness, from PISA scores to the genetic diseases to which Finns are disproportionately subject, due to a bottleneck in the past:

Though a genetically homogeneous population with a common suite of diseases might yield key information for research, on the human level, it is a tragic side-effect of a long, proud history of repeatedly snatching victory from the jaws of defeat on the margins of human subsistence. Like many enterprising frontier groups, Finns survived innumerable challenges, but suffered famines and many local extinctions, leaving a high and compounding tax of genetic homogeneity on the lucky few survivors. Today, one in five Finns carries an FDH mutation. These mutations result in three types of dwarfism, over half a dozen forms of neurodegenerative diseases, and several forms of sensory impairments, including deafblindness. The Finns are special and unique in their own self-conception, but their distinctiveness comes with a price.

Podcasts

The Unsupervised Learning podcast has criss-crossed many topics over the last few months:

Karl Smith: inflation, the debt crisis, China and the American tripartite class system

Here are the currently ungated podcasts all in one place.

I posted the conversations with Ramez and Samo consecutively by design. Ramez is a science fiction and fact author who is focused on the future, especially the domain of solar technology. Samo too is interested in the future, but he draws deeply on the historical literature to trace our upcoming possibilities. Ramez is cautiously optimistic about the future, while Samo discusses how little we truly know about the past.

David Mittelman and Linda Avey also discuss complementary topics. Linda is the cofounder of 23andMe, and helped set the framework for the genomic world we live in today. Over the course of our conversation, we discuss her 20 years in the industry, and the path she sees going forward. David’s company, Othram, is focused on using modern genomic technology to solve cold cases and bring forensics into the 21st century.

When I talked to Colin Wright, we addressed the two aspects of his career and focus: evolution and culture. Colin has made a name by defending the position that the idea that there are two sexes in humans is scientifically defensible, but Colin’s views come from his background as an evolutionary biologist. Starting in science, he eventually found himself embroiled in the “culture wars.” Alex Mesoudi is also interested in culture and evolution, but in this case, it is in the nascent field of cultural evolution. Mesoudi is the author of Cultural Evolution, a short, brisk textbook on the topic.

John S. Wilkins and Jason Munshi-South discuss the two ends of scale in evolutionary biology: macroevolution and microevolution. John’s focus is on species concepts, and whether they are useful or not. As a historian and philosopher of science, he was willing to get deep into the weeds with me on how people in the past thought of species, and how we should think of them in the future. Jason’s research is on one species: the brown rat. Though the rat is ubiquitous, it turns out we know surprisingly little about its genetics and history.

Finally, I talked to Karl Smith because I honestly wanted to know what was going on with the US’s macroeconomy. We discussed inflation, inequality, and trade. Overall, the conversation left me more optimistic than not. By popular request, I’ve also started generating automatic transcripts of the podcasts, as a perk for paid subscribers. In the future, I plan to have these be edited, but for now, the reaction to the transcript of Jason’s podcast has been positive.

You Make Me Want To Read

The Finland series prompted a lot of great comments. I want to highlight this particularly informative one from Henri because it suggests that if I read more I might have revised some elements:

…For example, when you refer to the Saami being "pushed out" north by the Finns, I fear we're mixing up two things here: first, the earlier Saami expansion into a huge area of northern Fennoscandia, and second, the slow, several millennia-spanning process of the Saami hunter-gatherer lifestyle being replaced by Finnish-style agriculture in the lakeland Finland.

Regarding the first, as convincingly shown by Ante Aikio [1], the Saami-speaking expansion from lakeland Finland or thereabouts to all of Northern Fennoscandia predates any pressure from, or even contacts with, the Baltic Sea Finnish tribes then residing during that time period mostly in modern northern Estonia. It is only later that those tribes slowly began to make their way to Finland through the South-Western coast. It is these Baltic Sea Finnish (itämerensuomalainen) populations that spoke the predecessor of modern Finnish and Estonian as well as some smaller languages. And as for the Saami, while unclear, Aikio speculates that the trigger for the Saami expansion might have been the higher demand for fur which the Saami traded through Scandinavian routes - hence the multiethnic Levänluhta findings, by the way.

Regarding the second, as far as I know, it's unclear how much this process was about actually driving the Saami away rather than outcompetition and/or assimilation. Looking at the most popular N1c* haplogroups of Eastern Finnish men, there is an argument to be made that those *male lines* are actually originally Saamic, which would indicate a wholesale adoption of the Finnish way of life. (Also, you could, for example, amuse yourself looking at the Middle Age Karelian and Savonian population expansions as a Saamic revenge of sorts.)

[1] Aikio, A. (2012). An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory. A linguistic map of prehistoric Northern Europe, 69-117. (Available online)

Over to you

As always, I welcome paid-subscriber comments and your reading recommendations and suggestions. They never disappoint.

Just to comment on two sentences:

- In the 9th century AD, a Swedish prince named Rurik built a fortification north of modern-day St. Petersburg. Rurik was a Varangian, one of the eastern Vikings journeying out of Sweden into the vast lands west of the Urals occupied by pagan Slav tribes.

- Before 500 BC, the languages spoken in the coastal East Baltic were likely related to forerunners of modern Scandinavian or Slavic languages...

These sentences are misleading and one of the reasons is the usage of misleading taxonomy. Before 500BC did not exist, neither Scandinavian nor Slavic languages. The term ‘Slavic’ is used after the 7th c.AC. The language mentioned was – Serbian language. Who ruled in Sweden in the 9th c.AC? In the last OT, we mentioned couple things about Beowulf and Geats (i.e. Goths - will write more about them) and also Vikings. Every text I’ve seen about Vikings hide an important fact proven by geneticists and archaeologists – Vikings were – (let say) Slavs. So, the ‘Swedish prince’ Rurik was a Viking and (let say) – a Slav, himself, who spoke Serbian language because at that time sc. Slavic languages (nor Scandinavian) still did not exist.