Got milk? Get -13910*T

A short genetic history of the 5,000 year human campaign to get the most out of milk

Americans love milk. After India, we are the world’s second largest producer of milk. Our nation’s dairy cattle are so productive that we are over a century into a seemingly permanent surplus problem. And thanks to the dairy industry’s powerful lobby and PR arm, that “problem” has given us decades of wholesome, health-focused ad campaigns including such ubiquitous slogans as Got Milk? And Milk, it does a body good. But milk doesn’t love all of us. And it doesn’t do every body good. Frankly, it never has, in all our millennia of existence as a species. Milk isn’t made for us and we weren’t made for it, at least not after that crucial narrow window when it nourishes and fortifies us all as infants.

But some of our ancestors fatefully discovered that milk needn’t only be a life-giving boon to babies, it can be an essential life-saving resource for adult humans, especially, it would seem, those in survival mode. Today some 30% of adult humans can digest milk and most of us can benefit from its bounty in secondary dairy products. This is the (startlingly recent) story of how a subset of humans seem to have remade themselves… for milk. And of geneticists progressively chipping away at the complicated story of how, where and why such a transformation might have occurred.

The US government absorbs some of the milk industry’s substantial surplus, distributing milk and cheese to communities it deems at nutritional risk. Today the federal government subsidizes the distribution of milk and milk products to children as part of their overall childhood nutrition programs to the tune of more than $10 million dollars per year. This is how regular shipments of powdered milk came to be delivered to 1990’s-era Native American towns of the Southwest. But as Arizona ecologist Gary Nabhan recounts in his 2004 book, Why Some Like it Hot: Food, Genes and Cultural Diversity, it all went to waste. Like 70% of the world and all indigenous New World populations, the locals were all lactose intolerant. Catchy jingles and nutritional value were no match for the reality that the substance was liable to make most of its recipients ill. Biology is no fool.

Nabhan found resourceful little boys repurposing the bounty their elders were dumping; they used it like fine-ground chalk to mark the foul ball lines on their dusty baseball fields. In 2004, that was just a curious anecdote illustrating human variation and how it impacts what we consume. But defying logic, within a few election cycles, lactose tolerance and its genetic underpinnings of all things were set to become an inflammatory and politicized topic. A 2018 New York Times piece, Why White Supremacists Are Chugging Milk (and Why Geneticists Are Alarmed), depicted white nationalists aggressively owning the trait of adult milk consumption as totemic to Europeans, drinking it with gusto in bizarrely swaggering validation of their whiteness. Whether this began sincerely or as a troll accepted too readily by credulous journalists, the idea of the milk-swilling white nationalist became a central trope for coming to grips with the American far right in the late 2010’s. Thus, political co-option tainted a story that remains one of genetics’ most fascinating and instructive for illustrating how evolution responds to cultural changes, and how quickly biology can “catch up” to the demands and amenities of a new environment. The tale of some adult humans’ ability to make use of milk sugar is one of evolutionary biology’s most intriguing.

Because continued functioning of the enzyme lactase allows the ability to process milk sugar to persist into adulthood, in the scientific literature lactose tolerance is today referred to as lactase persistence. Most humans stop producing lactase after the age of five. Normally indigestible, lactase breaks lactose into galactose and glucose, both of which the body can readily absorb. This same is true of all mammals; the stage when offspring can no longer digest milk sugar correlates strongly with the age of weaning, freeing the mother up to reproduce again. Here, humans have become unique. About 30% of human adults continue to process milk sugar, with frequencies rising above 90% among both Northern Europeans and pastoralist tribes like Kenya’s Masai. Because modern human biology as a science developed in Europe, and specifically in Northern Europe, scientists first defined human lactase persistence based on the variation and frequencies observed in their home region, where the more common and ancestral human form had actually become relatively rare through natural selection. In so doing, they mistook the rule for the exception.

Absent the lactase enzyme, upon ingesting milk, lactose sugar becomes available to the body's gut flora, which can cause bloating in mild cases, and diarrhea in the worst. Diarrhea today is little more than an inconvenience and embarrassment, but it’s worth noting that in the premodern world the attendant nutrient and water loss posed a serious danger. Dehydration and malnutrition when much of the population lived forever on the edge of famine could indeed prove fatal. So in the Neolithic, a mutation for lactase persistence would unlock a continuous source of calories from the cattle, sheep and goats (and in some cases, horses) herders were raising for meat and other byproducts like leather and wool. About 8 ounces (236 milliliters) of whole milk deliver 152 calories, 30% of them from lactose. Texas longhorn cattle, a breed not even raised for dairy production but for meat, can produce around 1000 liters of milk per year, so the equivalent of some 2,000 calories per day.

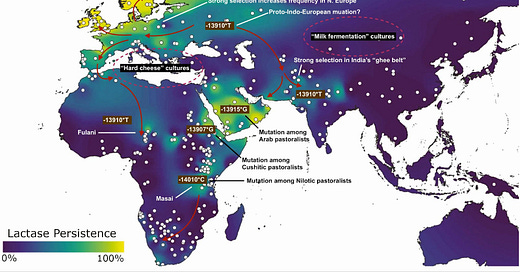

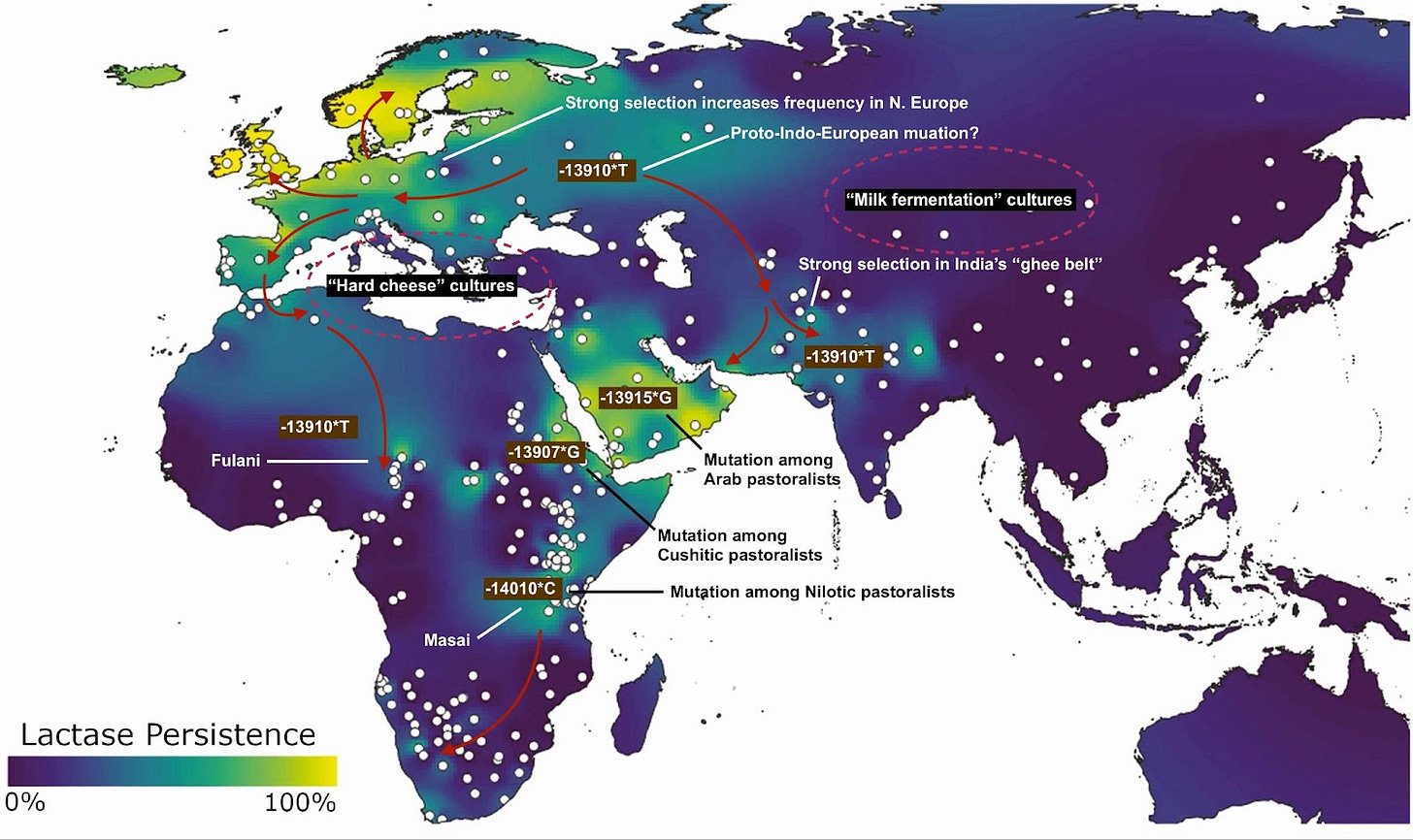

No wonder then that when scientists discovered the genetic region associated with lactose tolerance in Europeans, the gene LCT, basic population genetic statistics soon yielded evidence of the trait’s rapid and mass acquisition among humans over a very brief span of time. With the tools of this century’s first decade, geneticists quickly arrived at a model where cattle breeding in Northern European agro-pastoral societies during the Neolithic drove biological adaptation in order to make full use of the calorie-generating potential of their herds. Additionally, the same type of mutation in the dairying areas of Northern India, East Africa and Arabia, strongly suggested that common cultural conditions repeatedly triggered the same biological adaptation independently the world over.

But a closer examination of ancient DNA today doesn’t support this; it paints a different and even stranger picture. While the most likely starting point for lactase persistence’s evolution might naturally seem to be around the time of the Old World’s “secondary products revolution” some 7,000 years ago, when human societies recognized that the animals they were raising had utility beyond just their meat, ancient DNA traces a different path. Paleogenetic results rule out lactase persistence in Northern Europe being as ancient or monolithic in its origins as we had theorized. Surveying samples from individuals who died 2,000 years ago shows that the fraction of humans who could digest milk sugar as adults in Germany then was still far lower than today; at Rome’s height, evolution was just beginning its work on this handy trait, a process that would continue into the Middle Ages and beyond.

One mutation to bind them

For decades, Western doctors knew some adults could digest lactose, while others could not. The second category, lactose intolerance, was regarded as a peculiarity. Occasionally, a diagnosis was given to those afflicted with extreme gastrointestinal complaints. Aside from the unpleasant symptoms, easy breath-based tests can clarify whether you are lactose intolerant, like measuring hydrogen levels in your exhalation. When the body cannot digest lactose sugar, that leaves it available as food for gut bacteria that begin fermenting metabolism (this is the anaerobic form, the aerobic being oxidative). Byproducts of these bacteria’s biochemical activity are various chemicals, including hydrogen, which is absorbed into the blood, and eventually reaches the lungs. If someone is lactose intolerant, hydrogen is present in their breath a few hours after drinking milk.

By the 1960’s, researchers knew that the ability to digest lactose ran in families; the lactose intolerant were much more likely to have lactose intolerant parents. Once a biological process or trait’s heritability is established, researchers move on to positing and modeling possible underlying genetic factors, aided by analysis of pedigrees and inheritance. Lactose tolerance, as it was then called, manifests a textbook dominant inheritance pattern. That means that two lactose intolerant parents never have a lactose tolerant child, but if both are heterozygous for the trait (meaning they carry an operative lactose-tolerant copy of the gene plus a masked intolerant gene), two lactose tolerant parents can expect a lactose intolerant child 25% of the time (T for tolerant and t for intolerant, Tt⨯Tt would produce TT offspring 25% of the time, Tt 50% of the time, and tt 25% of the time). In a Mendelian framework, all you need is one of your two gene copies, or alleles, to be functional to manifest the trait. Intolerance is recessive; in a population where 25% of the aggregate alleles are intolerant, only 6.25% of individuals would exhibit intolerance (the probability of having two intolerant copies being 0.252). But early in the understanding of lactose tolerance, we lacked any deep molecular genetic comprehension of the mechanism through which the tolerance/intolerance phenotypes developed. Transmission patterns were established, and what the trait did. But beyond that, the molecular biology remained a black box.

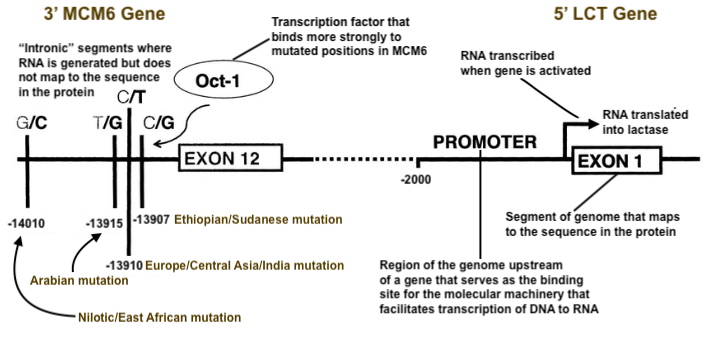

All this changed with the advances of the early 21st century once genomic studies could tag candidate genes for molecular biologists to investigate. The first attempts were genome-wide associations; basically hunting for correlations between an observed trait and variation in the DNA across individuals. Researchers divided their study sample into two groups, one lactase persistent, the other not. They immediately got a single clear and powerful hit. For lactase persistence, a part of chromosome 2 next to a gene called LCT, (which had already been identified in the 1990’s as the sequence of DNA that mapped onto lactase), was systematically different between persistent and non-persistent individuals. More precisely, a variant 13,910 bases upstream of the start of LCT was the strongest signal in the genome for predicting whether a person was persistent. At that precise point, the lactase persistent individuals could carry either the genotype CT or TT, while those who were not, always carried CC. This aligns with the dominance of persistence; only a single copy of T was necessary for the trait, while all the non-persistent probands carried two copies of C because of its recessive expression, the human default. This powerfully important single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) associated with lactase persistence was officially given the identification code rs4988235. Its position was base 135,851,076 on chromosome 2 in the gene MCM6, and for shorthand people referred to it as -13910*T, for the T mutation at the 13,910th position upstream of LCT.

How might this minor change in a gene outside of LCT impact the production of lactase? LCT activates at birth, but over time, it becomes deactivated or repressed. Gene activation or repression occurs through regulation, which can be caused by any of many variables, including other genes. MCM6, which is mostly involved with DNA replication, harbors regions that impact LCT gene expression downstream of it. The -13910*T mutation, with the switch from C to T, allows a piece of molecular machinery called Oct-1 to bind much more strongly to a region of the genome in MCM6. As copies of Oct-1 crowd around upstream of LCT, they begin to both compete for space and interfere with the arrival of epigenetic molecular factors that, in the normal course of development, halt transcription of the sequence producing lactase. Lactase persistence in adults emerges via the blocking of molecular dynamics that would gradually and inevitably repress LCT. It’s as if in the natural course of human development, a quiet janitor passing on his nightly rounds routinely pauses to manually switch off a particular bank of lights; in order to keep those lights on all night, a bunch of rowdy students mass in front of the light switch. They crowd so densely and pile up so many deep that the janitor cannot possibly wade through all of them, so the lights stay switched on.

The mechanism turned out to be simple, but this was actually the story of more than one mutation. Between 2000 and 2015, several other variants that correlated strongly with lactase persistence in the same neighborhood as -13910*T were detected. Oct-1 binds to the octamer motif, a small sequence of DNA that exhibits the sequence ATTTGCAT. The various mutations to T, G and C roughly 14,000 bases upstream of LCT, all modify the DNA sequence, producing a clear binding motif, resulting in an influx of Oct-1 (the rowdy students) that elbows out epigenetic repressor elements (the dutiful janitor) downstream. All the mutations produce the same end result: continued production of lactase into adulthood.

Because the early genomic studies were done among European populations, -13910*T, the “European mutation,” was discovered first. But -13910*T has a distribution far beyond Europe. It is also the mutation found in Indians, in particular among dairy-reliant peoples in the subcontinent's northwest. And within Africa, the Fulani of the western Sahel also carry this mutation. But further east in Africa, lactase persistence derives from different mutations in MCM6; Nilotic peoples like the Masai of Kenya have a mutation 14,010 bases upstream of LCT, while the Cushitic-speaking Beja of Sudan exhibit a distinct one 13,907 bases upstream. Across the Red Sea from the Beja grazing lands, Arabian pastoralists carry a mutation located 13,915 bases upstream of LCT.