Fortune favors the fearless: millennia of Austronesian maritime feats

Epic Explorers of the Stone Age: the full scope of Austronesian audacity, part 1/2

What follows is the first in a two-part exploration (read part two) into what genomics and ancient DNA allow us to confirm about the Austronesian people’s millennia of audacious voyages. Already know your Austronesians? Before we start, feel free to test the state of your knowledge with this quiz!

Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian Wars marks humanity’s first known attempts to dispassionately record historical events, in this case, a portion of the complicated tableau of maritime conquests, skirmishes and the shifting leagues and alliances that for decades embroiled naval powers all across the Mediterranean. Covering events in the final decades of the 400s BC, Thucydides’ seminal account delves into maritime and military technologies, examines the nature of power, the temptations of empire and considers the root causes of both wars of conquest and human groups’ expansionary impulse.

Athens’ and Sparta’s fight for hegemony over the limits of the known navigable world ranged across domains that included the islands dotting the Aegean Sea, a basin the ancient Greeks called Archipelago, our origin of the modern term, as well as such regions as the Dodecanese and Peloponnese itself. In these latter two storied locales, we discern the Greek root nésos, for island. But while the ancient Greek polities jockeyed for dominance over the isles and coastlines of their known world, another extraordinary population of human beings was already a millennium into its own maritime exploits, and on a scale beyond the Greeks’ imagining. For the Austronesians, the confines of the Greeks’ protected little Mediterranean backwater, with its single diminutive archipelago would have been as a placid bath tub is to a churning Olympic pool.

For four thousand years, Austronesian adventurers maintained a fearlessly voyaging culture that ferried entire family units from one newly discovered foothold to another on the coastlines of every continent save for the Greeks’ and Antarctica. But the Austronesians proceeded without any Thucydides to record their exploits, and indeed accomplished the most audacious of them before any human society had stepped into the historical age. By the time of truly global exchange, Greek naval preeminence was ancient history, but ancient Greek linguistic roots retained primacy among Europeans conjuring new words to describe novel peoples and locales. So in the general imagination, the most extraordinary seafarers of our species, masters of immense realms at the far ends of the earth from Greece carry Greek-tinged names. The vast archipelagos they discovered and settled are all familiar to us with that ancient Greek root nésos.

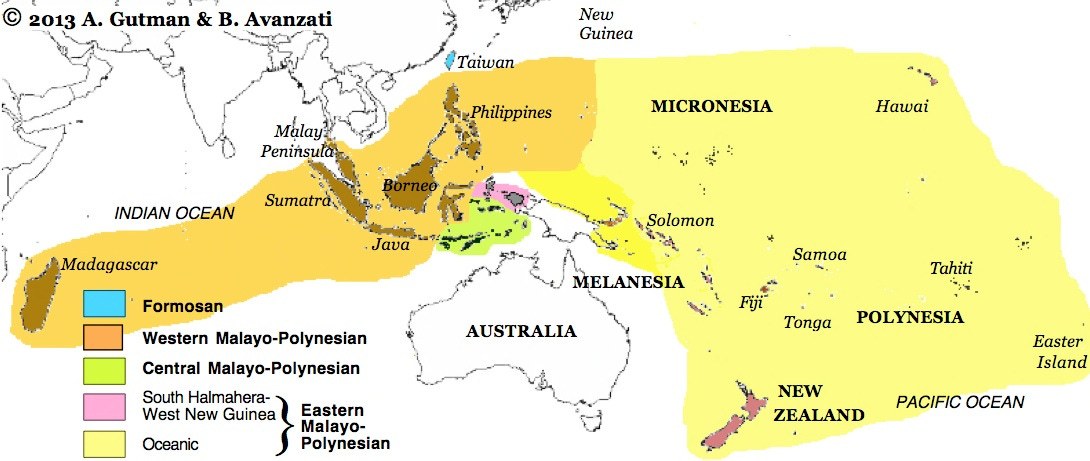

In their plurality, the people are genetically Austronesian. This includes all the peoples who settled the far flung archipelagos of maritime Southeast Asia, all the way across the Pacific from Easter Island at South America’s doorstep to Madagascar at Africa’s. The language family too is Austronesian. Europeans first thought of Indonesia in the 19th century as an archipelago of Indian isles. Then there is Melanesia, a label that arrived via the French for the collection of islands with darker complected Austronesian peoples; this includes New Guinea and storied islands just to its east like Fiji. North of these lies an arc of islands we call Micronesia, which includes such tiny locales as the Marianas, the Marshall Islands and Kiribati. And of course, we have Polynesia bracketing the vast expanse of the Pacific further eastward, everything between Hawaii, New Zealand and Easter Island, a zone that remained uninhabited until Austronesian speakers arrived after AD 1200.

Even though the greatest seafaring exploits of our species went wholly unchronicled as they unfolded in a prehistoric age, today the mounting power of genomics and especially ancient DNA allow us to trace an increasingly detailed outline of those millennia of astonishing accomplishments across a travelogue of exotic locales including the most isolated archipelagos on our water-logged planet.

The sweet potato’s world tour

In 1933, an unsuspecting expedition of Australian geographers and mineral prospectors entering the Wahgi Valley in highland New Guinea stumbled upon an entire world of over 100,000 humans totally unknown to the rest of humanity. This was one of the last “first contacts” with a society still living in blissful ignorance of the “outside world.” The existence of an entire isolated cultural universe was an incredible discovery for early 20th century scholars, who had posited that New Guinea’s interior was nearly uninhabited. In fact, with mild temperatures rarely deviating beyond the band between 60 and 70 degrees Fahrenheit thanks to its high elevation, these regions were actually much more densely populated than the tropical island’s malarial coasts.

But this was not their primal state. Barely two centuries prior, the sweet potato revolution transformed New Guinea’s agricultural systems, whose staple had heretofore been indigenous taro. Sweet potato cultivation yields about double the calories per hectare of taro, but more importantly, introduced sweet potato flourishes at up to 3,000 meters, whereas indigenous taro proves an unreliable crop above 2,000 meters. The interior, which had previously only been marginally habitable, much as those 1930s prospectors and geographers had erroneously extrapolated on the basis of its coastal zones, which remained the realm of populations more reliant on fishing, trade and low-intensity farming, turned out to be prime sweet potato country. As a bonus, the more palatable sweet potato was also far better pig feed, a turn of events which then also spawned a more complex agricultural system and diets with a healthier macronutrient balance.

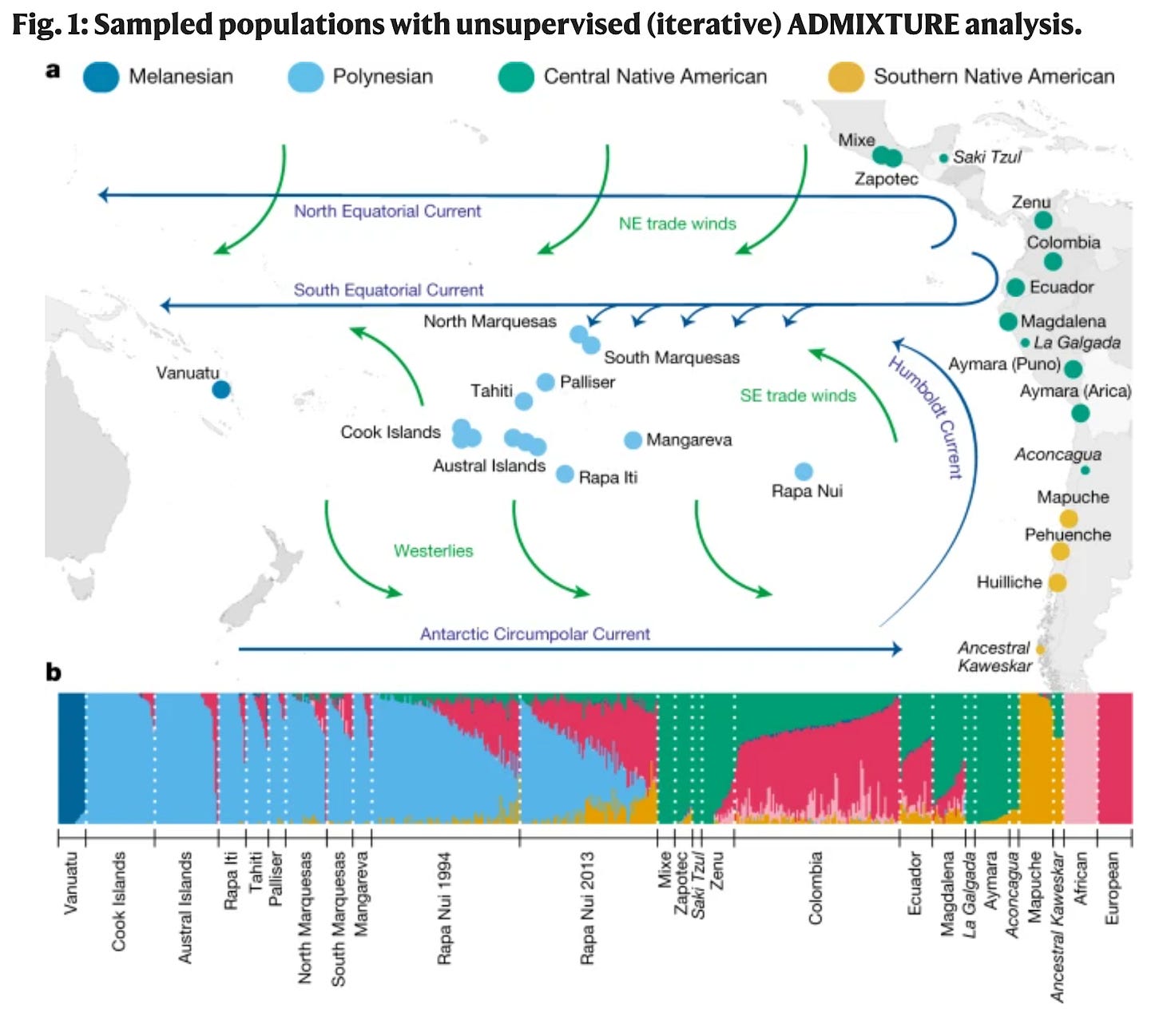

But where did this great revolution come from? Ultimately, the people of New Guinea owe the delivery of the sweet potato cultivar, which was domesticated in South America’s northern reaches about five millennia ago, to one of humanity’s most inexplicable and audacious demographic explosions. The sweet potato transforming New Guinea’s human geography is but a side-plot late in the grander epic of the Austronesians’ still largely mysterious journeys, maritime adventures that took them everywhere from South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to the distant shores of South America. Genetics can indeed demonstrate that the sweet potato cultivated in the New Guinean highlands nests within the pedigree of South America varietals, but this simply confirms and renders precise what a close listen already tells you: in the Andean languages of Quechua and Aymara, sweet potato is k’umar(a), while in Maori New Zealand it is kumara. A connection is unmistakable here between South American and Polynesian forms. But the sweet potato and its nomenclature spread yet further; in coastal New Guinea, where the natives, though genetically Papuan, and thus related to Australian Aboriginals, speak Austronesian languages, it is kumala It was in the New Guinea highlands, thousands of miles from its homeland, that the term for sweet potato seems to have morphed into its current form, kaukau. Somehow in the 19th century, the pidgin languages of the highlands settled on kaukau, Samoan for “flank or chunk of food.”

That startled first contact between white Australians and New Guineans in 1933 was but one of countless knock-on effects from the first contact between Polynesians and South Americans a millennium ago, which triggered not just the westward movement of crops, but, we can now confirm, also of people, back across the breadth of the Pacific. And at the same time that the Polynesians were pushing east, crossing the world’s largest ocean, the theretofore empty Pacific, some of their Austronesian cousins were venturing westward, probing the teeming shores of the Indian ocean, with ports of call from the island of Borneo to East Africa, and ultimately settlements as far west as uninhabited Madagascar.

The seed of this globetrotting began on the island of Taiwan, during the prehistoric Neolithic, at the historical moment when the Egypt and Sumerian civilizations were in their infancy, and China was not yet even ethnically Chinese. While the intrepid peoples of almost all of what L. L. Cavalli-Sforza termed the “great human diasporas” tramped through the forests and grasslands of God’s green earth, the Austronesians turned their back on the land, plunging out to sea as decisively as if they were taking a freeway on-ramp; to this people alone, the planet’s vast oceans were anything but daunting barriers; they were prehistoric byways to far shores.

Today only about 600,000 of Taiwan’s population are what the government labels indigenous, some 2% of the island’s 23 million citizens. But across the world, over 300 million people speak related Austronesian languages, descendants of those intrepid seagoers who ultimately staked out far-flung holdings across the globe, all starting 5,000 years ago from one small island off mainland China’s coast. They crossed the Pacific to the New World, bursting through an unmarked barrier that for 42,000 years had held back modern humans, who never ventured beyond the final frontier of islands just east of New Guinea. It was the Austronesians who pioneered Madagascar’s settlement, spearheading human adaptation to an island just off Africa’s eastern coast that had preserved its own unique fauna undisturbed for nearly 90 million years. With the Austronesian arrival, Madagascar became the westernmost outpost of Southeast-Asian rice agriculture, its highlands now more reminiscent of distant Bali than nearby Mozambique. Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, in Chile’s Easter Island, the most far-flung settlement of Polynesia, 2,000 miles west of South America, thousands of natives today continue to speak the Austronesian Rapanui language.

America and Austronesia

Norwegian archaeologist Thor Heyerdahl’s 1947 voyage from coastal Peru to French Polynesia on a balsa wood raft established his daredevil reputation, though his real goal was to bolster his unorthodox diffusionist theories about cultural evolution and mass migration. Heyerdahl wanted to demonstrate the feasibility of the Pacific having been settled from the New World, not from eastern Eurasia, the prevailing model then as now. The famous Kon-Tiki voyage, named for his raft, did not convince the scientific world, but the 5,000-mile voyage solidified Heyerdahl’s reputation as a scholar willing to put his extreme theories to the test. Unlike many heterodox thinkers, Heyerdahl had a conventional academic background, in his case, in zoology. The Kon-Tiki voyage was the culmination of a long-standing interest in Polynesian archaeology and anthropology dating back to undergraduate years spent studying private collections of artifacts. His argument for contact with the New World was multidisciplinary, based on the direction of currents, purported linguistic similarities between Amerindian and Polynesian languages, and a distinctive tradition of monumental statuary common to both Easter Island and Peru. Nevertheless, his bewildering and vividly detailed contention that bearded, red-haired, white-skinned sun-worshippers from the South American mainland but with distant Mediterranean roots (a legend with echoes in Peruvian mythology) were Polynesia’s first settlers struck even otherwise sympathetic mid-20th-century observers as unhinged, and as a throwback to out-of-fashion theories about lost white races more in line with 1847 than 1947.