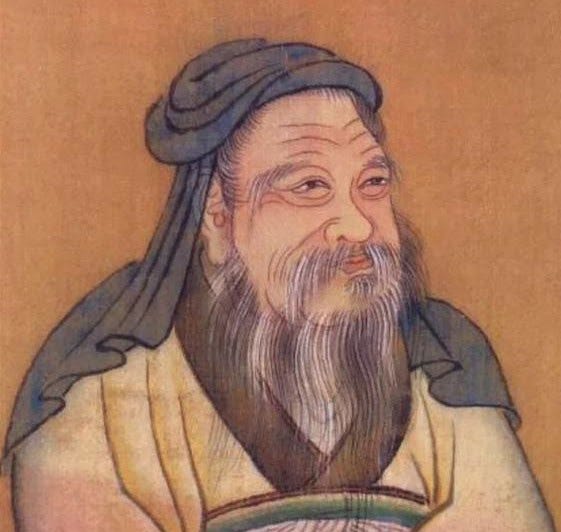

The original Chinese man

It all begins with the Zhou

The holidays are upon us. By way of thanking all of you for being so willing to support my fledgling substack project, this week I'm releasing a little set of year-end mini-posts. These are five quick daily reads about the state as I see it of five sectors I follow. Might have been perfect for raising the level of chitchat at a normal year's run of December parties. In 2020, I hope they'll edify if it's not your field and that you'll let me know what I'm missing if it's your bailiwick I'm reflecting on.

Thank you for reading, for subscribing, and for forwarding to friends who you think might enjoy. A quick administrative note: I'll be adjusting my Substack price levels upward in the new year so now is a great time to grab a paid subscription if you've been considering. Or to use Substack's gift option while the prices are lowest. Cheers!

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

It began 3,000 years ago

On January 20th, 1046 B.C., the armies of the Zhou defeated the assembled warriors of the Shang at Muye. The Mandate of Heaven passed from the Shang to the Zhou.

When I first read about the Battle of Muye, it was the date that jumped out at me (see Early China: A Social and Cultural History). Though there are still arguments about the specificity, it is a strongly likely date based on archaeological and astronomical evidence.

It’s a meme that China has “5,000 years of history.” This is false. The first historically attested dynasty is the Shang, which emerged approximately 3,600 years ago. And even the Shang are semi-historical, insofar as many of the details of the Shang society and state are known only superficially. The Shang are shadows to us, not flesh and blood narratives.

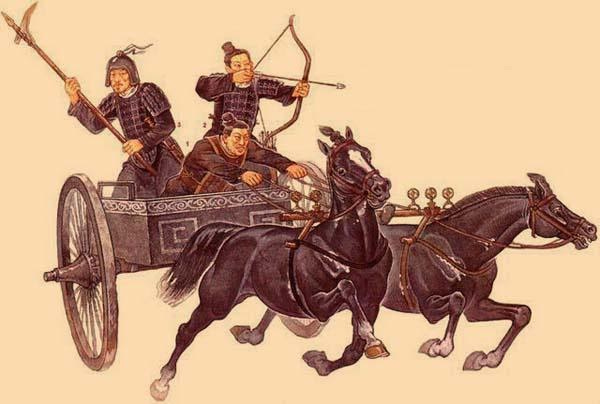

The oracle bones confirm the historicity of the Shang but the era of the Shang seems to be an alien one, sharing more with Bronze Age Greek Mycenae than the world of Confucius. The rulers of the Shang were not righteous sage kings, but warlords in the mold of Agamemnon the King, scourging the land, driving their enemies before their chariots. Though much of what we know about the Shang comes from their successors the Zhou, archaeology and oracle bones both seem to suggest that the Zhou depictions of barbarism were not entirely unfounded. The oracle bones record twelve precise ways in which the Shang sacrificed human beings to propitiate the gods.

The Chinese myth of 5,000 years of history is rooted in a pre-modern tradition of historiography which takes some myths at face value. These myths might preserve kernels of truth, but the further you go back the more garbled and inaccurate the recollections are likely to be. Before the discovery of the troves of oracle bones, some scholars argued that the Shang was a mythical dynasty. That is clearly false. I am also of the opinion that the earlier Xia dynasty is likely to prove identical to the Erlitou culture, the last prehistoric Neolithic society of the Yellow River basin before the Shang. But just because we know names does not mean that we know any real history in a substantive sense.

Despite the fallacy of the 5,000 years of history, the fact that the Chinese can date the victory of the Zhou with such specificity is amazing and testifies to the continuity of their civilization. In the year 1046 B.C. Ashur-Bel-Kala was king of Assyria. Greece was in its Dark Age. India was in its Vedic Age.

India and Greece were in an ahistorical period, as written civilization had collapsed. 1046 B.C. is an age of myth in these societies. Rama and Sita are shrouded by the mists of prehistory, and the chieftains of Dark Age Greece only dimly recalled in the epic poems of Classical Greece. In the Near East, civilization and history continued uninterrupted through the end of the Bronze Age, but the Assyrians, Babylonians, and Egyptians are not the cultural ancestors of the people who live in the region today. The Chinese have a continuous and living tradition that goes back to a precise historical point over 3,000 years ago. The Age of the Zhou informs the present age in a deep way that the travails of the kings of Nineveh do not in Iraq. The Egyptians take pride in their past, but the memory of the pharaohs is an academic matter today, not a history present in the lives of modern inhabitants of Cairo.

It began with the Zhou

When Confucius and his followers surveyed the past to imagine the best social and political system for human flourishing, they were focused on the example of the Zhou. King Wu. The Duke of Zhou, his younger brother. From what little we know it seems likely that the Zhou were liminal to the identity of the Han civilization incubated by the Shang and their predecessors. The Zhou emerged from the western borderlands of the Shang domains and had a close relationship with the Xirong barbarians who occupied what became the Gansu corridor and Qinghai. The Zhou were the marginalized.

It was Zhou distance from high culture and their lack of elite legitimacy that compelled them to engage in ideological innovations to justify their abrogation of the precedent that the Shang were the kings on high. The Zhou argued that the Mandate of Heaven had passed onto them from the Shang. They put aside the Shang personal God (Shangdi) in favor of the more abstract Heaven (Tian). These set templates for future Chinese political history. Whereas the rule of the Shang was justified by their organic authentic derivation from core proto-Chinese aristocracy, the Zhou had to legitimate their rule through more abstract and universal ideological frameworks. It was they who prefigured the modern. China qua China begins only with the Zhou, even if it was yet incomplete and unformed.

The righteous rule of men such as the Duke of Zhou did not come from their blood lineage or propitiation of an ancestral god, but through both their personal virtue and their adherence to cosmic principles. The Zhou could never deny that the Shang were authentic and highborn, but they rejected the old commonplace assumption that birth alone gave one the right to rule.

But all good things come to an end, and the Zhou themselves decayed and diminished over the centuries, eventually to remain only figureheads whose positions were inherited through lineage and not virtue, just as it had been with the Shang before them. Confucius, himself a scion of the Shang, propounded a philosophy of life and politics which aimed to restore the state of the world as it had been under the Duke of Zhou, with a state promoting morals and virtue in the persons of righteous rulers and moral officials. Whether the righteousness of the Duke of Zhou was a self-serving myth created to solidify the rule of a parvenu dynasty, or a true reflection of the life of an exceptional man, is less important than the fact that the ideal served as a basis for later Chinese civilization. The foundation of Chinese civilization.

The future reflects the past

Imagine a scenario where a British civil servant in 1890 encounters Plato in the flesh. What would they talk about? Classically educated Western men in the 19th century could actually converse with Plato, or at least they could recite some Greek to the philosopher. Additionally, they’d be familiar with his works in the broadest sense. But, Plato and a well-educated late Victorian or Edwardian Englishman would be different in many deep ways.

Plato was a pagan. The Englishman would be a Christian. This deep religious difference could never be dismissed. Whatever admiration a Westerner of 1890 might have for Plato, they would view the man and his philosophy as being highly incomplete. Ancient Greece may have planted some seeds for our civilization, but the West’s transformation under Christianity and the medieval period was significant. Christianity and the collapse of Rome mutated the Classical world to such an extent that the ancients would no longer have recognized it by 1000 A.D.

Now imagine a scenario where a Chinese official in the court of the last Qing emperors in 1890 meets Confucius and his followers. Obviously, there would have been some changes, especially the introduction of philosophical concepts in Neo-Confucianism that were clearly influenced by Buddhist metaphysics. But the core ideals promoted by Confucius could have received a full endorsement by a Chinese civil servant in 1890. Plato’s Republic may have been influential in the West, but it never became a template in the way that Confucius’ philosophy did. Confucius’s cultural successors in China continued to operate with the same intellectual currency down to the 20th century. And, as Confucius himself believed he was reconstituting the Zhou order, the Zhou ideal cast a formative shadow over future dynasties down to the modern period.

The long 20th century

Despite the upheavals of the 20th century, at the end of the day, China and its civilization remain rooted in Confucius. Today the Communist regime sponsors “Confucius Institutes” abroad to flex its soft power. To understand China, you need to understand Confucius and his world. To understand Confucius and his world, you need to understand the Zhou and the meritocratic world that they created atop the collapsed foundations of the hereditary Shang civilization. The uncouth Zhou illustrated the power of the civilizing process, turning rough frontiersmen into upright and just rulers. In China the noble is not born in the blood, he is created, shaped, and fashioned. Nobility is acquired, not innate. Just as the Zhou acquired the Mandate of Heaven at Muye in 1046 through force of arms.

Not that the intervening periods are irrelevant. Much of the bureaucratic infrastructure of China as the West encountered it in the 16th century dates to the Song period’s 11th-century reforms. The despotism of the imperial system began with the Ming, in the late 14th century. The development of “State Confucianism”, a fusion of classical Confucianism and de facto Legalism, comes out of the Former Han period, over 2,000 years ago, but well after Confucius.

But the roots of present Chinese civilization reach much deeper into the past than Western civilization, as they are thickly wrapped around the structure of China as it was at the end of the Bronze Age and early Iron Age. Dark-Age Greece, Assyria, and Iron-Age Italy bear little connection to the institutions and culture of the modern West and Near East. Chinese civilization, in contrast, stretches backward in time to the Duke of Zhou. Agamemnon is a myth. A name. The Duke of Zhou lives on as a biography from which moral lessons derive 3,000 years after his death. His name corresponds to a lived reality.

As China asserts its place as the most powerful nation in the world later in the 21st century, it behooves us to seek understanding by inspecting the foundations of its culture and civilization. They may not be 5,000 years deep, but a close look will show you a historical solidity beyond the ken of our conventional understanding whereby the Western ancients and moderns are connected by the thinnest of tendrils. The past echoes down the millennia and holds the present hostage. Even the most revolutionary of Communist apparatchiks are haunted by the world the Zhou made.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thank you again for reading, for subscribing and for forwarding to friends who you think might enjoy. A quick administrative note: I'll be adjusting my Substack price levels upward in the new year so now is a great time to grab a paid subscription if you've been considering. Or to use Substack's gift option while the prices are lowest. Cheers!

Great article Razib and thank you for an excellent primer to the foundations of Chinese civilization.

In 1000 BC no doubt Indian civilization was in an ahistorical phase, but the influence of that period on the present cannot be understated by any means. An Indian wedding today would be instantly recognisable to an Indian from 1000 BC. School children regularly recite a famous verse (sahanA vavatu) from the yajurveda from circa 1300 BC.

While I think the Indian and Chinese civilisations reach deepest to antiquity, what do you think about Judaism (Israeli civilization?) One can make a case that they were founded co-eval with the Indian and Chinese civilisations.

I gave a gift subscription to my brother. But I did not get sent to a page for payment. Is it automatically charged to my paypal? Or is something wrong?