You can’t take it with you: straight talk about epigenetics and intergenerational trauma

The true story of a powerful molecular process and how pseudoscience co-opted it

Every piece of IKEA furniture comes with a printed instruction manual of diagrams, its thickness and page count varying according to the complexity of the item’s construction. Imagine instead that each item required you to lug home another universal IKEA instruction manual. The manual would be a few meters tall, a ponderous compendium of every diagram-filled instruction booklet for every item in the warehouse. Diagrams or processes that apply to hundreds of distinct products could be cross-referenced and only appear once, but the document would still run to thousands of pages.

You would sit down to assemble your chest of drawers, your wobbly-legged high chair, and your pendant lamp, and for each disparate item, you’d consult the same unwieldy stack of comprehensive instructions. Except each time, you’d quickly find your way according to a system of personalized Post-It notes. There they’d be: color-coded tabs sticking out of the relevant tier of your universal manual. Some would simply mark your specific starting place and you’d be on your own. Others would include little hand-written notes, corrections, tips: “actually, do this step face-down on carpet so you don’t dent the veneer”, “do this one twelve times, not the six prescribed”, “skip this step and come back to it at the end, trust me, it’ll be easier that way”, etc. They’ll be in a familiar script: notes in your own hand guiding you, based on previous assemblies. Occasionally the handwriting might be your father’s, mother’s or even grandmother’s. Some of your Post-Its from earlier moves or IKEA binges would be more helpful than others. Some would have been revised, refined and overwritten multiple times. Under current conditions, the panicked ones scribbled under the stress of a sudden post-breakup move might no longer seem like the smartest approach, but you’d find yourself bound to follow them just as closely as the printed IKEA steps they modified.

That massive compilation of IKEA manuals is, of course, the DNA sequence each plant or animal carries in its every cell. And the colorful accumulation of custom Post-Its interleaved throughout each individual copy are the personalized marginalia we call epigenetics.

The mismeasure of molecular biology

In the last decade, sweeping mainstream-media claims about epigenetics’ expansive role in shaping our world have become hard to escape. I am a geneticist and happy to stipulate that epigenetics is responsible for a considerable amount of our planet’s dazzling biological complexity. And yet when someone comes at me with explanations of anything social and behavioral in humans predicated on epigenetic effects, I cringe like an astronomer informed that planetary dynamics determine my personal character (typical Capricorn hubris they might say). The details of your star chart might be precisely correct, yet I don’t have to tell you that no astronomer seriously ascribes comparable validity to astrology and astronomy. Epigenetics is a powerful and ubiquitous process in biology but entails no mechanism equipped to explain any of the multi-generational psychological phenomena it’s called upon to legitimize in media coverage, claims about which are both reliably overblown and entirely speculative. Let’s inventory epigenetics’ actual reach and influence; you can arrive at your own conclusions about whether it is plausibly, as headlines often claim, the transmission mechanism for such phenomena in humans as “intergenerational trauma.”

Epigenetics encompasses the molecular mechanisms that determine how relevant sections of DNA’s single universal instruction manual are interpreted and applied uniquely in each specialized cell, as specific pages of the manual are consulted (or not) according to each cell’s role in your body. It is one of the ways that the invariant DNA code manages to generate the nearly infinite structural and cellular diversity seen within every complex organism on this planet. A cell in my bone marrow producing blood, a cell in my liver and a skin cell bear minimal resemblance to one another; and yet each is built according to the instructions in that single universal manual unique to me… and their differentiation is largely a product of that flutter of post-it notes leafed throughout said instruction manual. Without epigenetics, I would be typing this as an undifferentiated blob of identical cells like a slime mold swarm. This reality is fundamental to epigenetics, but literary agents and newspaper editors have understandably concluded that such facts would not produce particularly attention-grabbing headlines or bestselling books.

Epigenetics as an idea has been with us for decades, since embryologist Conrad Waddington created the term in 1942, combining the words "epigenesis" and "genetics." He was trying to grasp how one single genetic instruction manual begat the vast diversity of cell types observed in a multicellular organism and how it shaped organismic development. Waddington’s concept preceded knowledge of the structure of DNA by a decade, so he lacked any detailed understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved. And indeed it is precisely on the scale of molecular biology that our appreciation of epigenetics’ actual power must begin today. Though in general discourse, the field has become far more closely associated with psychology, sociology and genealogy, if you corral a bunch of scientists working at the cutting edge of epigenetics, I guarantee you any shared appreciation of the majesty of their topic of research will be denominated in molecules, not sequelae of ancestral suffering among humans. This public misperception is almost wholly the outcome of the media’s preference for titillating headlines over science’s concrete and prosaic realities. And yet, taken for what it is, epigenetics is genuinely magical. Let’s explore its actual awesome powers.

Epigenetics as the dance of molecules

While classical genetics began with the Mendelian pedigrees tracing the transmission of traits, epigenetics unfolds through the physicality of molecular biology. Mendelian genetics manifests across generations, while epigenetics makes its mark, literally, on the time scale of cell divisions and DNA replications. Epigenetic processes are necessary to drive phenomena on a molecular scale, which ultimately build up to the level of complexity that gives us biology’s numerous disparate, rich fields, from neuroscience to physiology to developmental biology. In genetics, when we consider the transcription of genes and their ultimate translation to proteins, the classical DNA → RNA → protein explanation is a highly stylized reduction of extremely complex molecular phenomena. If Mendelian genetics is like the history of car makes and models, molecular genetics is the nuts and bolts of engineering and physics that power them.

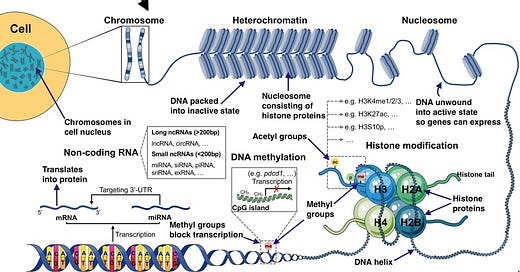

Since we live in the age of genomics, people usually imagine DNA’s A’s, C’s, G’s and T’s in one of two ways. There’s the elegant DNA helix, a polymer backbone spanned by nucleotide bases, and then there’s the bland sequence of letters often represented in plain text, line after line. But these are both reductionistic depictions. You usually find DNA wrapped around proteins called histones, which allows the long strands to be packed compactly within the cell’s nucleus. There, the 1.8 meters of a complete DNA sequence collapses down to 0.09 millimeters and winds together into structures called nucleosomes. During cell division, as DNA is replicated, these nucleosomes are condensed further into the chromosomes visible under the typical light microscope. Epigenetics operates at the interstices of these molecular structures repackaging DNA in the seemingly blank margins that are airbrushed out of colorful double-stranded helix visualizations.

Happily, for us, molecular biology as a field lends itself well to the possibilities of animation. The first two minutes of the below YouTube video illustrate the interactions that define the epigenetic process:

Humans have about 19,000 genes, but only a subset are expressed at any time in any cell. Numerous mechanisms drive epigenetic modifications, from the methylation of CpG islands of DNA promoter sequences that result in gene silencing to the more recent discoveries of the role of noncoding RNAs in gene regulation. But foremost among epigenetic mechanisms are the numerous chemical modifications (as in the video above, which focuses on methyl and acetyl groups in particular) to the histone proteins that shepherd and package DNA to control and regulate the differentiation of tissues and organs. For a single biochemical and developmental pathway, DNA supplies the orchestra musicians in the form of genes, while epigenetics plays conductor, bringing them together to summon a complex symphony of mechanisms and structures from the sequence of interacting chemicals. Summed together over tens of thousands of instances, this yields the elaborate and synchronized structural and physiological diversity of life on earth.

But epigenetics does not always run as a simple deterministic program; these dynamic molecular processes can be modified through environmental insults and stresses. Transcriptional factors, proteins that bind to DNA and regulate the reading-out of the sequence that ultimately produces proteins, are nudged and modulated dynamically by epigenetic forces receiving inputs from signals within the cell. Through this chain of molecular processes that runs from receptors on the cell surface all the way to proteins interacting with DNA, epigenetics even allows for an element of improvisation in the expression of the genome and activation of specific genes to tackle unexpected conditions. To wit, when nearly all organisms are exposed to very high temperatures, epigenetic forces turn on heat shock genes in direct response to physical changes to the structure of proteins on the cell surface. Think of an emergency response team swooping in to reduce inflammation and repair misfolded proteins and rip apart broken molecules for recycling at the site of your steam burn. These environmentally responsive epigenetic marks may then be inherited down the cell lineage, resulting in cellular-scale adaptation.

Histone modifications, and DNA methylation, are not the only epigenetic mechanisms. But the dynamics outlined above take you much of the way toward explaining how a single fertilized egg cell transforms into a complex organism with fantastically diverse, specialized tissues that can change and evolve over your lifetime, a miracle for which epigenetics deserves some author credits. Media reports highlight sensational and often spurious results of intergenerational and transgenerational epigenetics, focusing on the impact of this mechanism across generations. But molecular epigenetics as an instrument of gene regulation is constantly in play within the human body’s 200 distinct cell types across a human lifetime’s 10 quadrillion cell divisions. Yes, that’s 10,000,000,000,000,000 cell divisions or mitoses across which epigenetic phenomena are essential. The script of epigenetic changes replays endlessly in every individual, in every organism, and is therefore usually highly deterministic. This is why humans look like humans and potatoes like potatoes. This reality rather than nebulous speculations about intergenerational trauma should frame how we understand epigenetics.

If only it weren't for that blank slate

In mammals (as in most vertebrates) the most basic reason transgenerational epigenetic transmission of anything particularly significant seems unlikely is the fact of a “factory reset” of the epigenetic marks during meiosis when sperm and egg are created, and a second one right after fertilization, when sperm and egg fuse to produce the zygote. In contrast, in mitosis, all conventional, non-reproductive cellular replication that does not that lead to sperm and egg cells, the pre-customized histones are usually duplicated, and their epigenetic marks are transmitted to the new copies. DNA or histone methylation can also be inherited through the cellular division process. But this is constrained to the life cycle of the individual. The marks are erased and the epigenetic instructions routinely reset and wiped clean early on in embryogenesis, as the single fertilized egg develops into a highly differentiated and complex fetus and then a child.

How then to explain results like those from Sweden where grandfathers’ and grandmothers’ food deprivation was correlated with increased mortality of grandsons and granddaughters respectively? The p-values in these studies were below 0.05, so they were statistically significant (in other words, even if the default hypothesis is true, the probability is less than 5% that you’d get that result, so perhaps consider the alternative). Studies like this can see print because the design and results fall within scientific guidelines, so they technically meet a journal’s gatekeeping standards. But at this point, as most readers are aware, just because a study is statistically significant does not mean it will stand the test of time or its results be broadly replicable; the p-value tells you only the probability of the given outcome assuming a certain model, and sometimes unlikely things do happen. But it doesn’t tell you anything about all the comparable studies that never saw print because the statistics didn’t cooperate, nor does it reveal all the datasets selectively discarded because they turned out to be junk. A study, or studies, may show something, but the truth of a matter is established through many replications, ideally with controls for confounding variables that may be driving some of the intergenerational associations (obviously, more than genes are transmitted within families; folkways, customs and habits are acquired through imitation).

In addition, trite though the chestnut that correlation does not equal causation might be, in the case of transgenerational epigenetic transmission it cannot be avoided. Extraordinary claims contradicting over a century of established Mendelian genetics and seventy years of scientifically validated molecular biology require extraordinary evidence. In humans, many roadblocks remain to establishing that inherited characteristics in subsequent generations are due to environmental shocks in prior ones, not least that you cannot perform randomized controlled experiments. Inferences must be from observation studies, correlational or indirect (“natural experiments” like famines). Deeper digging reliability shows that cases where epigenetic marks seem to have been inherited transgenerationally actually turn out to be conditional on the existence of a conventional DNA mutation being passed on within the family. These mutations may induce a byproduct of distinctive epigenetic marks, so they are caused every generation by variants natural selection or drift favors. The causal role of the epigenetic variant in a trait may hold, but its transmission across generations due to the epigenetic mark is a mirage. Epigenetics in this case is downstream of conventional Mendelism. It is like some fine print addendum automatically regenerated anew by a DNA mutation every generation. A mere footnote to a well-characterized classical genetic process of inheritance.

In plain English, any case for the mechanism required to posit the inheritance of human epigenetic variation is a royal mess. That doesn’t mean that transgenerational epigenetic transmission doesn’t happen; it is well documented in plants and C. elegans (“worms”). A small body of candidate studies in humans also require further follow-up, but even these remain the object of strong skepticism from most biologists. Contrary to what headline writers and pop psychotherapists might like you to believe, thus far, epigenetics is terribly implausible as a factor in theories of human intergenerational trauma.

Epigenetics across the generations

The first paragraph of Wikipedia’s intergenerational trauma entry burnishes its veneer of unassailable scientifically-grounded basis, giving epigenetics prominent billing:

Transgenerational trauma is the psychological and physiological effects that the trauma experienced by people has on subsequent generations in that group. There are two types of transmission: intergenerational transmission whereby epigenetic changes are passed down from the directly traumatized generation [F0] to their offspring [F1], and transgenerational transmission when the offspring [F1] then pass it down to their offspring [F2] who have not been exposed to the initial traumatic event. Exposure includes when the offspring is in utero.

Descriptions like the above blur the fundamental difference between epigenetics and Mendelian genetics, misconstruing both as mechanisms of inheritance across the generations. Reality is a bit different as noted earlier. Epigenetics is defined by concrete biophysical changes to your DNA packaging and marks that impact how genes express themselves rather than changes to the heritable genes themselves. These changes can be temporary or persist across many cell divisions. Within cell lines, like muscle tissue, the epigenetic marks determining which genes are expressed or repressed can be passed on to new muscle cells throughout your lifetime. This is a feature; you don’t want muscle cells randomly transforming into brain cells. In most animals, especially mammals, this is the sum total of epigenetic transmission, modifiers shepherding specific cell types within an organism’s lifetime.

But in some rare cases in some organisms, epigenetic marks persist for generations (but remember, even these results have alternative explanations). Intergenerational epigenetic transmission means that the changes affect both the offspring and the parent (and perhaps also the grandchildren, in the case of a female fetus whose eggs are impacted during in utero development). The theory of transgenerational epigenetic transmission extends it a step further, with offspring passing the epigenetic marks down to multiple future generations. This is the form of epigenetic inheritance requisite for hypothesized intergenerational trauma, because it is not a correlation due to the same stress event occurring to the parent and fetus simultaneously, but an event whose impact is transmitted biologically across many generations. A cause that echoes down through the generations.

A simple illustration of genuine intergenerational transmission that requires no imaginative gymnastics would be famine which induces stress on the pregnant mother, her female fetus and the female fetus’s own eggs, where all exhibit epigenetic responses due to a simultaneous and singular external shock. The longest possible chain of generational impacts of this event would reach to the children of a female fetus in utero at the time of the external stressor (the third generation). And if the fetus were male, the effect could not persist beyond him in the second generation, because males continuously produce new sperm cells throughout their lifetime; no mechanism exists for them to transmit the famine-induced changes. Any posited intergenerational “transmission” cannot then be literal transmission, but at most correlation due to the same shock contemporaneously impacting parent and offspring (and if the fetus is female, egg cells). Multiple generations, yes, but only in the way that multiple generations living through a catastrophic earthquake carry its scars in various forms for the rest of their lives. In contrast, under transgenerational transmission, the stress marks induced by the external shock are thought to be copied generation after generation so that the effect persists much longer. If transgenerational transmission does occur in humans, you might expect descendants of the Armenian genocide to be biologically impacted by that event more than a century on.

But we don’t even need to take this line of hopeful speculation seriously, because epigenetic transmission across multiple generations almost certainly does not occur in humans at all. Mammals generally would be unlikely to exhibit transgenerational epigenetic transmission due to the simple facts of our reproductive biology. Though transgenerational epigenetic transmission grabs the public spotlight, it accounts for far less than 1% of the research published that can be classed as “epigenetics” (and this is on any species, least of all humans!). Instead, for humans and all complex organisms, epigenetics remains both incredibly important and ubiquitous, but solely as a cellular and developmental phenomenon. To understand epigenetics in its full power, you talk to a molecular biologist that works with DNA, not a therapist probing the pain points of your family history.

So why are we still talking about this?

A 2018 New York Times headline asked, “Can We Really Inherit Trauma?” The subhead continued: “Headlines suggest that the epigenetic marks of trauma can be passed from one generation to the next. But the evidence, at least in humans, is circumstantial at best.” The mainstream media is heavily implicated in sensationalizing the field of epigenetics, so The New York Times in particular needed to spotlight researchers' misgivings and bring its readers back to reality. It needed to compensate for a decade of breathlessly covering cutting-edge findings on the field’s outermost margins and playing up their revolutionary implications, unmoored from the unglamorous context of epigeneticists’ actual core work, mostly in molecular biology and gene regulation. Headline gold though it might be, foregrounding the inheritance of trauma as epigenetics' raison d'etre is like earnestly suggesting that astrological horoscopes give deep insights into astronomical phenomena.

What the media says matters because few laypeople read scientific papers; they get their information on science from the likes of The New York Times, which has put the total weight of its sober-minded reputation behind such tantalizing headlines as “Fathers May Pass Down More Than Just Genes, Study Suggests” and “The Famine Ended 70 Years Ago, but Dutch Genes Still Bear Scars.”

And realistically (especially among certain generations, ahem), in the 2020’s laypeople are even more likely to pick up any impressions of epigenetics from YouTube videos with clickbait titles like “Can Trauma Be Inherited?” (167,000 views). Posted on a channel with 781,000 subscribers called “SciShow Psych,” this offers a classic example of what passes for “science communication” anymore. The video leads with a sensationalist and barely defensible intro, but for the sake of propriety tries to clean up the mess in the second half of the episode with caveats and factual qualifications. After the clickbait, SciShow Psych’s host reminds the viewer that the idea of inheritance of trauma through epigenetics is tentative, suggestive and unproven and concludes by offering many other much more plausible ways that trauma could be transmitted from parents to offspring.

Watch the whole episode, and you can’t avoid the rather deflating (or reassuring, depending on your goals) conclusion that realistically, trauma probably cannot be inherited. But 45 seconds into the episode, the host is still asserting that “trauma can affect future generations, too,” without a trace of hesitation, caution, or foreshadowing that he will soon reverse himself on precisely this point. Speculations about epigenetics and intergenerational trauma without caveat take up fully two minutes and 30 seconds out of five ( leaving aside that he misdefines epigenetics as the “study of what can be inherited from parent to child biologically, but outside of the actual letters of your DNA”) before the host begins dutifully bringing the narrative back to earth, deflating all those balloons he floated to get the party started. For anyone who peeled off early, the video looked like a full-on epigenetics-is-the-mechanism-behind-intergenerational-trauma fest.

For the broader public, tantalizing suggestions frequently encountered enough risk swiftly mutating into rock-solid facts and theories that can be taken as givens in serious discussions. Members of the lay public who have heard about epigenetics are likely to associate it with neo-Lamarckian ideas about the transmission of acquired characteristics (a giraffe routinely stretching its neck out and then passing on a long neck to its offspring who in turn do the same in the next generation, etc.) rather than the workaday nuts and bolts of the body’s molecular machinery.

In 2021, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau released a statement about the controversy around Catholic schools for Aboriginal Canadian children where he stated:

…we must continue to learn about residential schools and the intergenerational trauma they have caused. It is only by facing these truths and righting these wrongs that we, in partnership with Indigenous peoples, can move toward a better future.

What jumped out at me was the casual deployment of the concept of “intergenerational trauma,” which seems out of nowhere to have become ubiquitous. Google Books’ Ngram search feature tells us that the term did not exist before 1985, with its use increasing gradually until 2012 when it hit an inflection point and began to shoot up.

Searching Wikipedia for “intergenerational trauma” will take you to the page “transgenerational trauma.” The edit history shows that the entry was created in 2012 (transgenerational and intergenerational trauma chart the same Ngram pattern). The definition section clarifies the scope and mechanism:

Transgenerational trauma is a collective experience that affects groups of people because of their cultural identity (e.g., ethnicity, nationality, or religious identity)...The mechanism for transmission of trauma may be socially transmitted (e.g., through learned behaviors), through the effects of stress before birth, or perhaps through stress-induced epigenetic modifications.

Epigenetics as a mechanism driving intergenerational trauma immediately seems logically suspect because surely the antisemitic pogroms in Russia in the early 20th century or the Armenian genocide a few years later, for example, would have left a mark upon the culture of Russian Jews and Armenians in distinct and socially heritable ways with sequelae down to the present. So why even speculatively bring epigenetics, a biological mechanism, into the mix? One basic reason is that peer-reviewed science publications lend prestige and credibility to whatever they touch. After all, the public often professes to “trust the science,” so the ultra-empirical-sounding field of epigenetics gets drafted into buttressing faddish sociological ideas around intergenerational trauma. And it’s a shame because as we have seen, epigenetics is meaningfully ubiquitous; these processes supervise every healthy human’s cellular machinery. Epigenetics does not unfold over generations, but we can thank our lucky stars that our bodies are buzzing with epigenetic mechanisms every waking moment of our lives.

Genetics and evolution matter on the macroscale, epigenetics on the micro

Finally, even if transgenerational epigenetic transmission does occur, it has to be vanishingly rare and not very impactful in any studied organisms. Why? Simply because, for a century, conventional geneticists, using Mendel’s framework of mutations passed onward through pedigrees, have studied how characteristics are transmitted in the real world. If many traits were strongly dependent on (previously unnoticed) epigenetic insults in the few most recent generations, that would distort these results, and the deviations would emerge rapidly, as particularly well-studied organisms with distinctive traits might change after every novel shock. The existence of the entire field of transmission genetics negates the idea that epigenetic effects passed through families could ever be common, even in the case of plants where this is a well-known phenomenon. If epigenetic transmission was ubiquitous, then the textbooks of Mendelian genetics could never have been written. And stepping beyond basic science, applied fields like plant and animal breeding are underpinned by the Mendelian framework; epigenetic interruptions transmitted across generations could be economically disastrous, as farmers’ breeding projects would no longer yield the desired traits valuable to them.

But there are even deeper evolutionary biological reasons to be skeptical of epigenetic transmission. The persistence of fixed epigenetic marks across generations would undermine the plasticity and flexibility that epigenetics enables in individuals on a molecular scale. As a molecular mechanism, epigenetics grants cells and organisms the flexibility to adapt to short-term changed conditions and stressors; a high level of fidelity in future generations would verge on epigenetic determinism. If the duplication and passing on of DNA to future generations should be a high-fidelity process that maintains the characteristics natural selection has preferred, epigenetics should be a local adaptation mechanism that allows organisms to track environmental volatility without locking in one generation’s adaptations in perpetuity.

The purview of epigenetics is different than that of Mendelian and evolutionary genetics. The methyl and acetyl groups being chaperoned by enzymes around the DNA and its assorted ancillary structures are part of the nanoworld that operates beneath our notice. About one percent of our body’s cells are replaced every day, and this is where epigenetics reigns supreme, dictating the specialized qualities of each cell and nimbly adapting to external inputs over an organism’s life cycle. In contrast, Mendelian and evolutionary genetics operates over generations and millennia respectively. Rumors of a revolution here where one field dethrones another are wildly exaggerated. Instead, each discipline focuses on the scope and scale of its domain, careful study of them allowing us to understand how simple biological systems can develop, grow, and over the scale of lifetimes, generations and eons, evolve and thrive.

Our genetic code remains that tower of universal IKEA instructions, faithfully copied, plonked down and consulted anew at each cell replication. And we are lucky to have epigenetics’ confetti of handwritten Post-Its interleaved among its thousands of pages; they guide and customize our development as incredibly complex organisms. But hopeful rumors that these little marks, these bits of marginalia, these ephemeral scraps of advice, are running the show, as heritable as the tome they annotate, are at best a motivated fantasy. Transgenerational trauma may well meaningfully exist, but pinning its validity on a system of Post-It notes that flutter away at the slightest breeze (or at each meiotic event) is a non-starter. And all to the good. Ultimately, epigenetics is a case where you can’t take it with you.

Thanks for writing this! Finally a primer we can send to all of our friends

Someone give this man a University Chair and a megaphone. Thank you very much for this essay, Razib; and Happy Holidays to you and your family.