You can’t beat us if you join us

Strategically minting new citizens: lessons from Rome & the US

Part 1 of 2. Related: When in (the) America(n century), do as the Americans do

Ours is an age of flux and flow, trade and transfer. The species’ newest ideas, goods and indeed citizens shuttle ceaselessly around the globe, whether as packets of high speed data, stacked on container ships or wedged into budget jets. Our age-old penchant for memetic diffusion of ideas remains relatively uncontroversial, whether it’s a new fracking technique or the latest corporate management system (although perhaps my francophone friends alarmed by the speed with which le wokisme has stormed their shores begin to disagree). The movement of goods, from Chinese-made iPhones to jeans stitched in Bangladesh, and American outsourcing of services, like customer support to the Philippines and legal document review to India, have long elicited grumbling. But that these anxieties and frustrations nag a globalized citizenry quite universally is illustrated in for example the UK’s exit from the EU and on a smaller scale, Japanese wariness of cheaper foreign rice. And yet still, by and large, both democratic and authoritarian states have embraced Adam Smith’s conclusions about trade’s benefits to both parties.

The eternal fly in the ointment is instead human migration, whether legal or illegal, skills-seeking recruitment or refugees desperately fleeing precarious homelands. The advent of a digital global culture diffused via TikTok appears far less threatening to those who inveigh against “globalism” than the arrival of millions of newcomers who variously work the fields, pack overcrowded apartments, compete for university slots and strain public services. But that ship has already sailed. Crashing fertility rates in the developed world and the insatiable economic appetite for labor coupled with vast pools of young Latin Americans, African and Asians lacking local opportunity make global migration inevitable. The question is not whether the future will be immigrant, but how our societies adapt to such an inevitability.

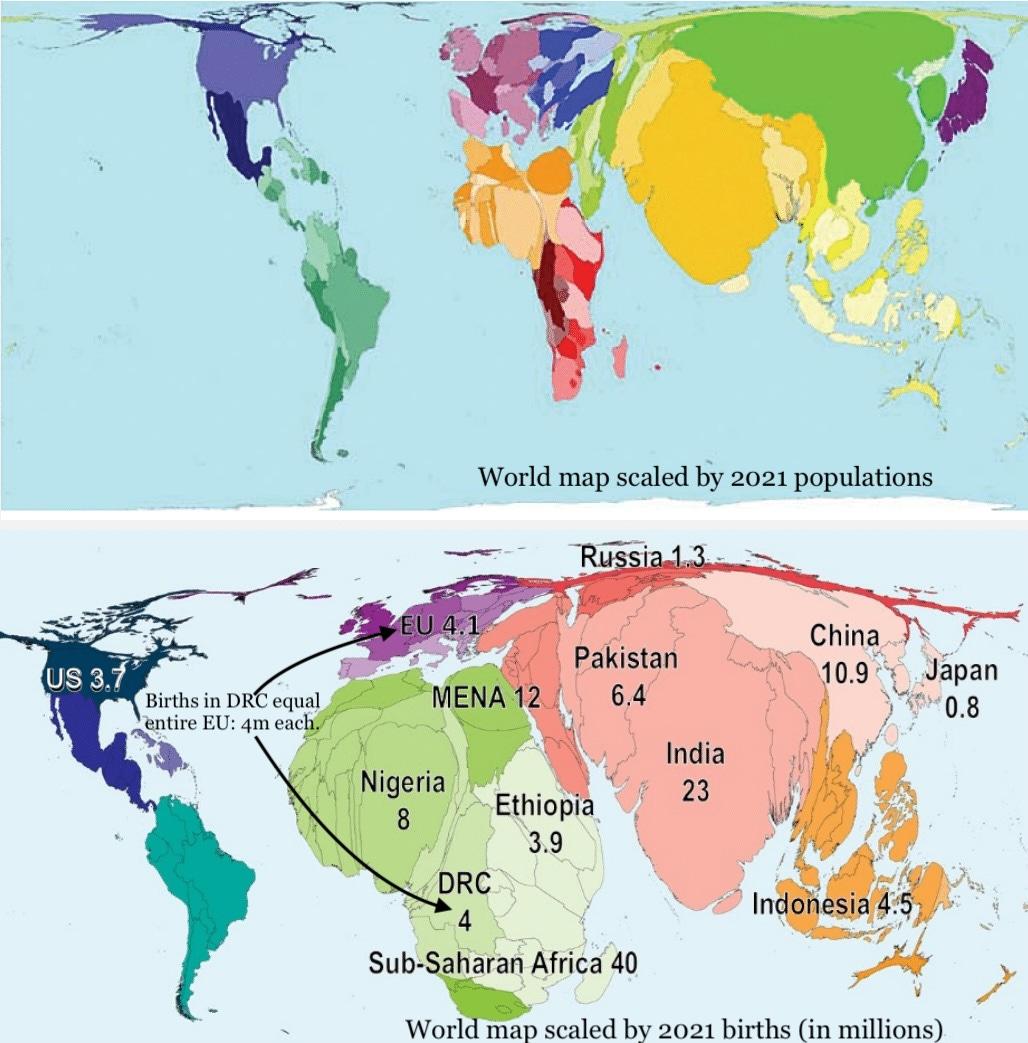

And on this point, it would seem that the issues that rankle most are always the nature of the migration and its scale. In 2021, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Ethiopia each recorded nearly as many births as the entirety of the European Union. The planet's demography one to three generations in our future is being written today in maternity wards across the globe. In the long term, a shriveling and ever more geriatric “Fortress Europe” doesn’t have a prayer of indefinitely turning away many-fold greater numbers of young Africans and Middle Easterners streaming across the Mediterranean. Today, nearly 14% of the US’s population is foreign born; numbers not seen since the decades between 1870 and 1910 (and steadily rising from a 1970 nadir under 5%). But it’s not just the US. More than 16% of Germany's population is foreign born, as is 14% of the UK’s and 10% of France’s. This has already driven a backlash illustrated in the rising electoral fortunes of far-right parties both French and German (the National Front and the AfD), as well as the Conservative Party's collapse in the UK while far-right third parties surge (Reform UK and previously UKIP). But it’s not just Europe. The United Arab Emirates, home to global hub Dubai, is 88% foreign born, tiny powerhouse Singapore 46%. And it’s not just wealthy nations. The Ivory Coast, an economically dynamic magnet to its neighbors’ citizens, is today 10% foreign born.

Migration dynamics will shape this century, but too often they are reduced to uninformative buzzwords like “globalism,” “invasion” or “GDP growth.” Nuance and demographic details matter. All migration is not equal. Some streams go nearly unremarked, others become a flashpoint. Nearly 20% of people in Sweden were born outside its borders. Finns have traditionally been the largest foreign born contingent, with 1.5% of people in Sweden having been born in Finland. But of course these quiet neighbors from across the Baltic are not the stripe of immigrants over whom right-wing activists wring their hands, and they are not the reason that in 2022, 18% of Swedes voted for a party with Neo-Nazi roots. About 0.7% of people in Sweden were born in Somalia, but given certain extreme cultural incompatibilities and the Somali burden on the Swedish welfare state, with employment rates as low as 20% and fertility over double that of ethnic Swedes, Somali born migrants have induced panic in the notoriously calm Swedish public, something the Finnish born entirely fail to arouse.

Humans have always been on the move. It’s in our genes. And with the very occasional exception, like Australia, local populations have not been able to stem the constant flow of genes and memes from elsewhere even when it’s propelled by nothing more urgent than our innate migratory urges. In many instances locals are replaced in a few generations. We adapt, we assimilate or we’re written out of the story. Outcomes vary, and the migrants’ background compared to the host country, their culture and aims, and their simple numbers, all impact the success rate of assimilation. The 20,000 French Calvinist refugees to Prussia in the late 17th century had little long-term impact beyond shifting the German accent of Berliners. Frederick William, Elector of Brandenburg, welcomed these skilled migrants, who also shared the religious confession of the House of Hohenzollern. In contrast, Welsh cleric Gildas had this to say in the 6th century about the arrival of Anglo-Saxons to Britain:

Then all the councillors, together with that proud tyrant Gurthrigern [Vortigern], the British king, were so blinded, that, as a protection to their country, they sealed its doom by inviting in among them like wolves into the sheep-fold, the fierce and impious Saxons, a race hateful both to God and men, to repel the invasions of the northern nations.

Not only did the Anglo-Saxon language replace Celtic British, the Christian religion disappeared from Britain, the urban Roman economy collapsed, and now we know from paleogenomics that a substantial number of Germans and Scandinavians opportunistically arrived in eastern England, replacing the natives. The Anglo-Saxons’ fateful quality was that they were aliens entirely lacking in and uninterested in Romanitas, while quantitatively their numbers were vast, with whole villages of men, women and children transplanted from the North Sea’s southwest shores to eastern England. Here, the Anglo-Saxons replaced the Britons culturally and genetically.

These timeless negotiations between one human group and another attain urgency again today, for example as Macron’s France grapples with rising tides of both anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim fueled flight to chauvinist far-right options at the ballot box. Beyond simple formulations like “America is a nation of immigrants” or “When in Rome, do as the Romans do,” a deeper reading of history offers lessons here. France is a republic of long standing, a former colonial power built on centuries of immigration. So is the US and so was Imperial Rome. So what informative parallels do France’s mounting factional frictions find deep in American and Roman historical dynamics?

Like the US, France is a nation of immigrants; the French were the first people to undergo the demographic transition, with modernization driving a decrease in fertility that necessitated early 19th-century immigration from other European regions. Here I find certain aspects of 19th-century America and how they set the stage for 20th-century resilience and coexistence relevant as the American experiment hums enduringly along, its 250th birthday now in the offing. Meanwhile, Rome’s well documented experiments in empire, immigration and assimilation endured for over a millennium. The barbarian Germanic peoples’ völkerwanderung between the third and sixth centuries has been implicated in the Roman Empire’s collapse, but upon closer examination, I find the reality of how Germanic people fit into Rome’s historical arc both germane to our debates today and more nuanced than is often acknowledged.

Here I will consider the Roman case and in a second companion piece (linked below), dive into the American one.

When in Rome, do as the Romans do

Imperial Rome’s multicultural reputation precedes it, but Republican Rome’s diversity was notable as well. Romulus and Remus’ mythological founding of the city has long been associated with their war-band kidnapping the Sabine women. This kind of myth almost certainly reflects anthropological realities in primitive pre-state tribal Italian societies, where marauding patrilineal kin groups would conquer an area and establish fortifications, around which cities coalesced. A figure like Romulus almost certainly existed, leading a freshly mustered group of young men to occupy a site along the lower Tiber. The men needed wives, but lacked the connections to arrange for appropriate marriages. Upcountry neighbors of the Romans, the Sabines were Italic-speaking, but not Latin, and the easiest targets for a rapid raid whose aim was to literally “flesh out” the citizen-body. By the 6th century, the deep connections between these mountain tribes and the lowland Latins are again confirmed by Sabine noble Appius Claudius and his retinue’s arrival to the city. Leader of a peace faction among the Sabines, he threw in his lot with his enemies. The Romans in turn accepted him and his lineage into their patrician nobility (the gens Claudii would go on to contribute to the Julio-Claudian Dynasty, with the Emperors Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero being direct patrilineal descendants of Appius Claudius).