Other posts in this series: Our African origins: the more we understand, the less we know and What happens in Denisova Cave stays in Denisova Cave... until now.

Twenty years ago we had the origin of modern humans all figured out. By “modern humans,” I mean Homo sapiens with those signature high cranial vaults, gracile builds and dynamic cultures. The qualification modern is essential because the human lineage goes back millions of years, and before the expansion of H. sapiens 60,000 years ago, other human populations coexisted alongside our forebears, from Neanderthals in Europe to assorted Homo erectus populations in East Asia. But we knew these were “evolutionary dead ends,” branches diverging off from the trunk of human ancestry that led up to us, and dying off as our ancestors expanded inexorably, with their advanced technology and superior intellect. The part about advanced technology and superior intellect wasn’t always said out loud, but it was clearly implied by scholars like physical anthropologist Richard Klein of Stanford, who took a dim view of whether Neanderthals even had the ability to speak in his 2004 book The Dawn of Human Culture. We still saw our cousins as upright apes, forgotten prologues to the real human story.

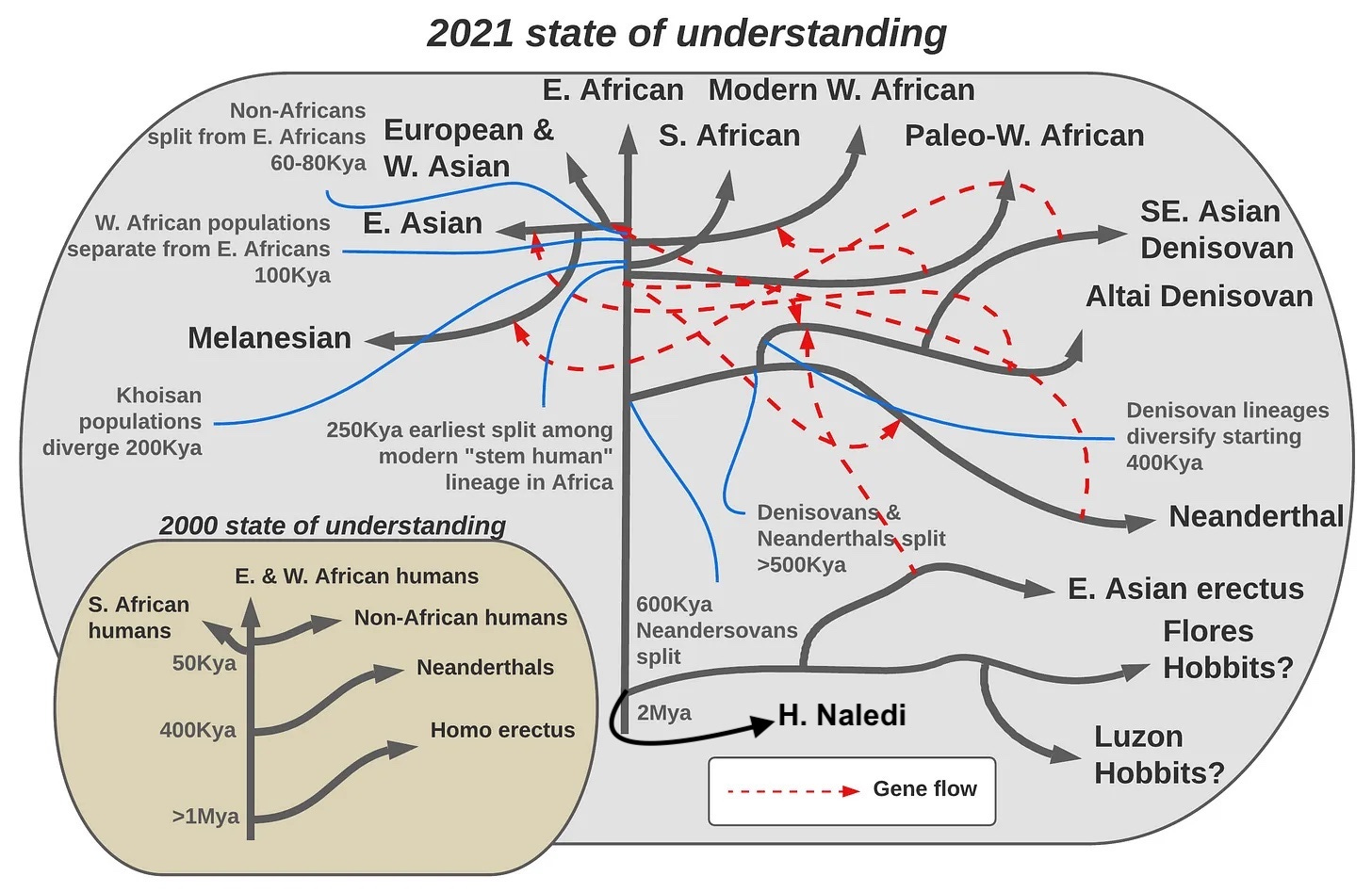

Today almost everything we had figured out then is wrong. We didn’t understand the origin of modern humans, and we’re still in the process of unpacking all the complexity as more and more findings come to light. Beginning in 2010, ancient DNA made plain that Neanderthals and their East-Asian cousins, the Denisovans (after Denisova cave in which their remains were discovered), were not evolutionary dead ends; their traces continue on in us. The modern human expansion 60,000 years ago was not universal across our species. It defined only the African side-branch that swept across Eurasia (and beyond, to Australia and the New World!), and had far less impact within the ancestral continent. The story within Africa was more complex, as the various proto-modern populations emerged independently and fused together to give rise to our own lineage. Not only did the humans who migrated out of Africa mix with our Neanderthal cousins, but in East Asia, we mixed with Denisovans, and their distinct genes live on in people in East and Southeast Asia, Australasia and the New World. Not only did we absorb Neanderthals and Denisovans into our own lineage, but Neanderthals themselves mixed with early migrants out of Africa. These latter were not our direct ancestors, but definitely our very near cousins. Rather than a tidy scenario of migration from a small population outward that replaced all of our relatives in one fell swoop, the reality we’re today coming to grips with is that the emergence of modern humans involved multiple migrations, complex interactions with our distant cousins the Neanderthals and Denisovans, and that it was only the last in a series of massive worldwide changes that occurred over hundreds of thousands of years.

In 2000, we had the tidy and elegant story of a single East-African tribe 60,000 years ago that exploded onto the evolutionary scene like an act of God, the descendants of mitochondrial Eve who were destined to push aside all those who had come before. In 2021, the story is no longer either tidy nor elegant, but sprawling and baroque, and we have still not unraveled all the knots and gnarls. The expansion of Africans out of the northeastern edge of that continent 60,000 years ago marked the denouement of a plot arc that had been running for nearly a million years, whose fine-grained details still remain to be worked out. Rather than a revolution and explosion, we now discern an evolution and an emergence.

Mitochondrial Eve was just one mother of us all

Sometimes dramatic retellings of science have a way of getting out of control. The geneticists who went along with the coinage of the term “mitochondrial Eve” were surely aware that the label alone was going to captivate the public, while in the scientific community the focus would be on technical details of their phylogenetic tree. By hitching their star to the name Eve, they immediately activated resonances and metaphors that communicated to the public just how significant and novel these revolutionary findings were. With modern molecular methods, they were probing the origins of humanity itself, right back to our first ancestors that left the “African Eden.”

Prior to the 1980’s, human evolution had mostly been the purview of paleoanthropologists well versed in fossilized bones and manipulated stones that bore hallmarks of human shaping. This dogged crew of paleontologists and archaeologists had only a small number of remains to analyze because until quite recently, humans had never been numerous. Identifying a new species was often frankly a matter of intuition and judgment based on one specimen, more of an art than a formulaic conclusion from large, bias-proof datasets. Nevertheless, the fascination with human evolution gave paleoanthropology an outsized public profile. Paleoanthropologists Richard Leaky and Donald Johanson, the latter of whom discovered Lucy, recorded a combative scientific debate in 1981 at the American Museum of Natural History. There was enough public interest in the clash that it was televised on network television, with Walter Cronkite presenting.

Into this glamorous domain stepped the geneticists. Culturally they couldn’t be any more different than the paleoanthropologists who spent months outdoors, digging in sun-baked corners of Ethiopia, Kenya and South Africa. Genetics meanwhile was a lab science mostly focused on the analysis of variation of model organisms grown in controlled conditions, whether these be green peas or swarms of Drosophila melanogaster. Its practitioners spent their days in climate-controlled laboratories, or in the case of a few theoreticians, scrawling formulae on blackboards. Though it was a science long focused on humans in the medical domain, it had had little to say about the evolution of our species, humans not being laboratory animals.

But James Watson and Francis Crick’s discovery of DNA as the substrate of Mendelian inheritance had transformed the range of empirical possibilities available to geneticists. By the late 1960’s, assays testing DNA and its protein proxies could probe evolution directly by looking at how it affected molecular variation. In the 1970’s, with these tools of molecular comparison, biologists began to wade into questions of human origins and evolution, when biochemist Allan Wilson and colleagues argued for the relatively recent origin of the hominid lineage after performing comparisons between the biomolecules of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas (from antibodies to amino-acid sequences).

Wilson debuted the now famous result that chimpanzees and humans exhibited 99% genetic similarity, implying that the two lineages were closely related. While Leakey came down on the side of a very ancient date for our lineage’s split with great apes, at a minimum more than 10 million years ago, Johanson argued for a more recent separation, closer to 5 million years ago, which would position Lucy as a possible ancestor of modern humans (by the 1990’s, Leakey graciously conceded that Johanson and the geneticists were correct in his book Origins Reconsidered). When genetics came down definitively on the side of Johanson, many paleoanthropologists were shocked at the power of the new science and the arrogance of its practitioners (the best modern estimate using genome comparisons yields a divergence between chimpanzees and humans six million years back).

But Wilson wasn’t done. He wanted to look directly at DNA, which had much more variation than proteins or antibodies, and which could yield more far-reaching evolutionary conclusions. Instead of analyzing how species related to each other, Wilson’s lab sought to probe how individuals and populations within a species were related to each other, and thus infer the evolutionary history of our own species. But before the advent of now-ubiquitous polymerase chain reaction methods in the 1990’s, which allow for the massive amplification of minute amounts of DNA, the paucity of raw genetic material imposed a sharp limitation on these analyses.

Wilson and his students realized their best bet was to collect a type of DNA that was very copious, rather than being present in just trace amounts: mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). While each human cell has two copies of nuclear DNA across 23 chromosomes, there are often 1,000 mitochondria per cell generating energy, each with its own strand of DNA. From any given tissue there is far more mtDNA than nuclear DNA to begin with, and today we also know mtDNA is more structurally stable and does not degrade as fast. A recent paper using 2,000-year-old samples from mummies in ancient Egypt found as many as 18,000 copies of mtDNA per each one of nuclear DNA. To increase the amount of usable mtDNA in their analyses even more, Wilson’s student Rebecca Cann extracted them from 145 donor-provided placentae, as these were particularly rich in usable tissue (two further samples came from proliferating cell lines, one of these from Henrietta Lacks).

During the development of the new zygote from the fusion of ovum and sperm, the mitochondria are inherited only from the egg at fertilization (the human egg has at least 100,000 mitochondria). Therefore, mtDNA is passed exclusively from mother to daughter, in a single unbroken chain extending back into the past. The unique properties of mtDNA, from its large quantity available in experiments, to the fact that it generated a perfect maternal genealogy in evolutionary analyses, allowed Wilson’s lab to finally probe our species’ more recent origins. After identifying 195 variable genetic positions on the mtDNA across 147 women they were finally able to draw fine-grained conclusions on the scale of thousands of years, rather than millions.

Looking at the variation Cann found in the mtDNA, she and her colleagues constructed a phylogenetic tree of our direct foremothers, back to a common ancestress (the British science writer Roger Lewin termed her “mitochondrial Eve” to Wilson’s chagrin):

The primitive plot above illustrates a few things that have now been reconfirmed many times over the last 40 years. There is a geographic structure across much of the tree, so that women from New Guinea cluster with other women from New Guinea, and women from Europe cluster with women from Europe. But there are exceptions, because the ancestral variation was not perfectly sorted by population as our species expanded from its homeland. First, one group of Africans split off first from all other human populations early on, indicating that continent’s special role in our species’ origins. The first division in our species’ history was between Africans and non-Africans. Second, there were African women found in other branches of the human family tree that were otherwise non-African. What the mtDNA tree reflects is that Cann and her colleagues found Africans harbored the richest ancestral genetic variation by far among modern humans, implying that Eurasians, Australians and Amerindians probably emerged out of a single original population with a homeland somewhere in Africa. As that tiny subsample of humans left Africa, they underwent a series of bottlenecks that reduced our lineage’s genetic variation as they pushed north and east in small groups.

Additionally, using the fact that mutations accumulate at a regular rate, offering a built-in “molecular clock” not unlike radiation or carbon for dating purposes, geneticists in Wilson’s lab concluded that our African lineages began to diversify 90-180,000 years ago, while the Asian lineages diversified 53-105,000 years ago and the New Guinea lineages 28-55,000 years ago. They had created a human genetic evolutionary tree with specific dates on the branching events that reflected our species’ migratory history over the last 200,000 years.

Upon publishing these results, the geneticists swiftly discovered they’d interposed themselves directly into the middle of an internecine debate among paleoanthropologists fighting over the recent history of our lineage. On one side were scholars exemplified by Chris Stringer at the British Natural History Museum, who asserted that fossils reflected the recent origin of our lineage in Africa and the replacement of Eurasian hominids like Neanderthals. Stringer would simply point to the shocking divergence between Neanderthal skulls and those of modern humans, letting the visible differences make his argument for him. In contrast, his rival Milford Wolpoff at the University of Michigan argued that humans across the world have deep roots in their local regions, and our commonalities are the product of continuous gene flow between populations. The two stances were sometimes called the “recent African origin” and “multiregional” models, and the differences of opinion often got heated (Stringer and Wolpoff have both confirmed to me that they have a tense relationship to this day). As in the 1970’s, the geneticists again came down definitively on one side. Cann’s quantitative results drawn from genetics delighted Stringer and elicited skepticism from Wolpoff.

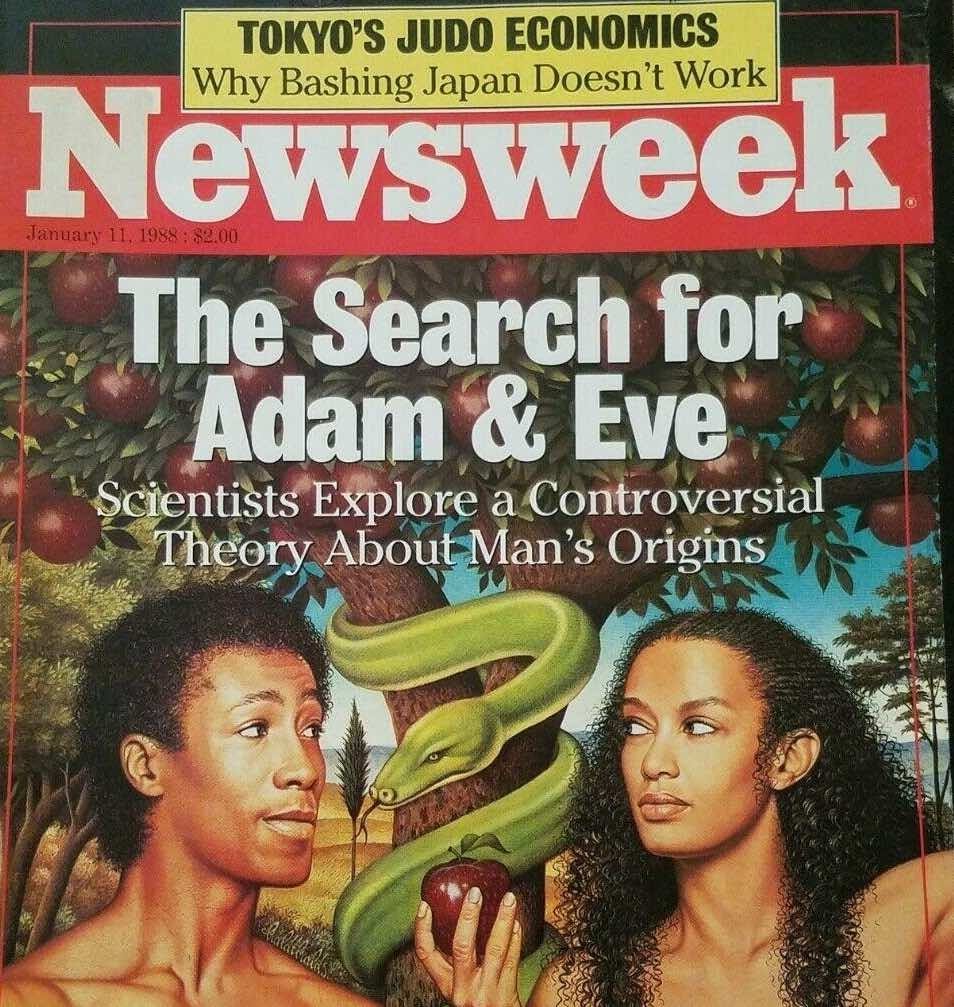

Mitochondrial Eve soon became a cultural phenomenon, spawning both a Newsweek cover and a PBS documentary. This led to some common impressions not always supported by science. Mitochondrial Eve was a real woman, but it was never true that she was the only woman in her generation from whom we are descended. The vast majority of the human genome is autosomal, meaning neither the Y or X chromosome, nor the mtDNA. For technical reasons, autosomal segments of DNA are harder to analyze, so the original work on our African ancestry focused on mtDNA and that single ancestral woman. With the techniques of the 1980’s, much of human evolutionary genetics was like a dark street, and Cann and her colleagues hunted for the key to our history under the proverbial lamppost, because that’s where the best light was. It is true that this ancient woman harbored the last common ancestral mtDNA lineage of all living humans that continues down to the present in a direct line from mother to daughter. But what of all her contemporaries who also contributed genetically to humanity today? As soon as the daughter of any woman in that ancestral population begat sons, no matter how many or how prolific they proved, her contribution to posterity could no longer be tracked along that unbroken mtDNA line. Her mtDNA was out of the race forever.

Hindsight now makes it clear that Cann, Wilson, and their colleagues, were basing a lot on a single, somewhat arbitrary, line of evidence. But hindsight also has proven them broadly correct. Luckily for us, a fitting key was under that lamppost. In the 1990’s, it was confirmed that Y-chromosomal Adam is also African. He also flourished in the range of hundreds of thousands of years ago, not a million years ago. At the same time, the autosomal genome of humans shows a pattern where Africans internally are the most genetically diverse, then Eurasians, then the peoples of Australasia and finally the New World. Just as Cann had found for mtDNA. Finally, in 1997 some genetic material from only partially fossilized Neanderthal remains was retrieved, and the mtDNA seemed clearly very distinct from all modern humans. Stringer and Cann were right after all, and the very DNA of Neanderthals backed them up.

By the early 21st century, Cann’s bold predictions seemed scientifically vindicated. Modern humans were a recent African species, without admixture from any other lineage. It was a simple enough storyline to emblazon on “We are all Africans” t-shirts that Richard Dawkins promoted. But then scientific advances had to go complicate a good thing.

Neanderthals rediscovered

The first revolution in the genetic inference of human evolutionary history involved using the DNA of modern populations and trying to make sense of the resultant variation by applying different models that could explain the patterns. DNA of modern populations indicated that internally Africans were the most diverse, followed by West Asians, then Europeans and East Asians, and then Australasians and people of the New World. A model that most efficiently explains this is that humans expanded out of Africa in a series of migrations that caused bottlenecks, with variation lost through random genetic drift at each successive step. The people of the New World were hit by three bottleneck events, first out of Africa, then to East Asia and finally to the New World. That’s why indigenous Americans, despite being distributed the length and breadth of two entire continents, are among the least genetically diverse human populations. West Asians were impacted by one drift event alone, the migration out of Africa. That’s why they were the most diverse non-Africans. Population genetics is an elaboration of simple rules and frameworks as applied to breeding populations that then explain genetic variation. The goal with inference here was to work back to the simplest, most eloquent models that can explain the patterns of variation we observe.

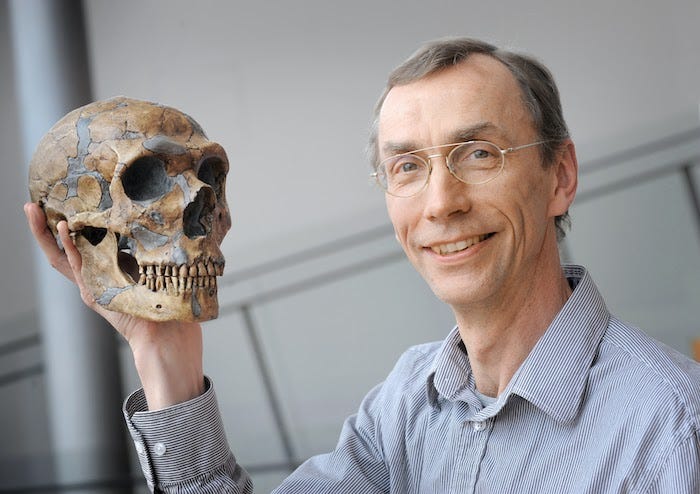

But the second, unanticipated, revolution in genetic inference came courtesy of ancient DNA. In the 1980’s, Swedish geneticist Svante Paabo was engaged in a quixotic quest to get usable information from ancient remains that had not fully degraded. Paabo set about becoming the first paleo-geneticist. DNA turns out to be a pretty robust and durable molecule (which stands to reason, because as the substrate of inheritance in all species, excess fragility would be a huge liability). Happily for science, a consequence of this is that DNA doesn’t disintegrate immediately, and some residual fragments often turn out to be decipherable long after an organism’s death and decomposition. Paabo first focused on Egyptian mummies, and the published results were such rubbish that colleagues still whisper today that the rather bewildering outcomes were probably due to contamination by a member of his lab’s own DNA. But unperturbed, he continued in his efforts, finally hitting pay dirt in 1997 when his team succeeded in extracting readable mtDNA from Neanderthal samples. Work on mammoths in the 2000s followed those early efforts (good practice for archaic hominids), but his most sensational finding by the end of the decade focused on Neanderthals. First, his team sequenced the whole mtDNA region from a Neanderthal in 2008, confirming that this population’s maternal ancestry lay outside of the genealogical tree of modern humans. But next the team looked at the whole genome and stumbled upon a surprising result: non-African modern humans were discernibly more similar to the Neanderthal sample than Africans were.

For over twenty years, the conventional wisdom within genetics had been that modern humans expanded out of Africa, totally replacing all indigenous groups. The genetic tools of the 2000’s, which began to scan the genomes of modern humans, did not detect any strong signature of exotic ancestry. The conclusion then was that the out-of-Africa model with zero admixture was likely correct. African expansion with total replacement defined the rise to dominance of our lineage over Neanderthals. There were dissenters, but they were in the minority. A 2004 paper whose title boldly proclaimed that “Modern Humans Did Not Admix with Neanderthals during Their Range Expansion into Europe” has more than 300 citations today. In contrast, a 2006 paper estimating 5% of the modern human genome may have been from Neanderthals and other archaic human populations has garnered only 50 citations (for what it’s worth, the authors were not that far off).

But all orthodoxies give rise to heresies, and as far back as 1998, some geneticists pointed out that the available empirical data using only the mtDNA phylogeny simply did not answer the question of whether modern humans had Neanderthal ancestry as conclusively as many paleoanthropologists had understood from Wilson and his students (Leakey himself, in Origins Reconsidered, reports that some geneticists privately argued that Wilson’s group was making too much of mtDNA). But theory has only so much power to persuade the public, even the scientific one. In 2010, all three billion Neanderthal base pairs from a single ancient individual in Denisova cave in Siberia were sequenced, allowing us to go beyond theory. The day had come to simply count differences in genetic positions, which finally made it irrefutable that all modern humans outside of Africa had 2-3% Neanderthal ancestry.

But there was more in Denisova cave than just Neanderthals. At the time they released the draft of the Neanderthal genome, Paabo’s group also revealed mtDNA had been retrieved from the pinky finger of an ancient woman, and that mtDNA lineage already appeared different from anything previously discovered. The individual was dubbed “X-woman,” and she belonged to a population more distant from modern humans than even Neanderthals. By the end of the year, the lab had sequenced and analyzed her whole genome. It turned out that she was genetically closer to Neanderthals than to modern humans (notice here that this is a case where mtDNA and nuclear DNA give different phylogenies), and that her lineage, informally known as Denisovan, seems to have contributed 5% of the genome to people in contemporary New Guinea, of all places.

Combining genomics and ancient DNA, geneticists had independently refuted the total-replacement plank of the old out-of-Africa model. For decades, on the basis of fossil evidence, Wolpoff and his colleague Erik Trinkaus had been arguing for a theory of hybridization, but their reasoning always fell on deaf ears. The power of ancient DNA was such that with a single publication in 2010 entire paradigms were overturned and a wholly new understanding emerged. In 2010, Wolpoff emailed me that “losing the propaganda war was not fun.” Ultimately though, he got the satisfaction of seeing many of his ideas integrated into the new orthodoxy.

But this was not the end of it. Within Africa, soon paleoanthropologists and geneticists would team up to modify the simple idea that all modern humans descend from a single “East-African tribe” (as a typical PBS special from the 1980’s would have had you believe).

More on that in Part 2 & 3…What Happens in Denisova Cave Stays in Denisova Cave... until now (for paid subscribers).

Related: Out of Africa's midlife crisis - on bottlenecks, crashes and what diversity really looks, Here be humans We keep discovering how much less of humanity is… us and Dragon Man ascending: two geneticists discuss the latest paleoanthropological discoveries.

One point that has always boggled my n00b understanding of this field is what unit of measure geneticists are using when they speak of humans and chimps being 99% the same genetically, but then also say that modern humans have 2-4% DNA in common with Neandersovans?

Clearly those two statements are each using a radically different metric, which never seems to be explained! (/old man yells at the clouds)

Can anybody enlighten me please?

What is a 2000-year-old mtDNA molecule like? Is it still a circle? Is it still inside of a mitochondrion?