Uncanny Neander Valley

Modern human-Neanderthal interrelatedness grows curiouser and curiouser

By curious chance, humanity’s reckoning with our Neanderthal kin dovetails with our reckoning with evolution; Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species in 1859 and the first ancient human remains accurately identified as a new species were discovered in Germany’s Neander Valley in 1856. In the 160-odd years since Neanderthals joined the human family tree, their status has been revised repeatedly, from primitive brutes to ancestors, to an evolutionary dead end, back to ancestors. Unsurprisingly, our read on Neanderthals, savage or sensitive, tends to be conditioned on whether we currently see them as forebears or evolutionary failures. A generation ago, the scientific consensus in paleoanthropology was that they were an offshoot that went totally extinct 40,000 years ago. Scientists like Stanford’s Richard Klein, in his book The Dawn of Human Culture, suggested they may not even have had language, a depiction that reduced them to brutish primates exhibiting the bare simulacrum of humanity. Today, we know that all of us have some Neanderthal ancestry, and their depictions in the media are markedly more soft-focus and sympathetic than even 20 years ago. Scientists are now reevaluating their read on the Neanderthal ability to generate symbolic culture, with book titles like The Singing Neanderthals: The Origins of Music, Language, Mind and Body. Perhaps massive Neanderthal brains, among the largest in the history of the human lineage, were not just used for rudimentary hunting and gathering after all?

The last year has seen papers digging deeper into the swelling sea of our lineage’s both modern and ancient genomes, now complemented with copious ancient Neanderthal genomes. Together this wealth of data has begun revealing the fuller picture of key dynamics of our lineage’s relationships with our Ice Age cousins. Why do some modern populations have more Neanderthal ancestry than others? Does it owe to mixture from different Neanderthal groups contributing distinct portions across Eurasian populations? Perhaps useful Neanderthal adaptations drove the retention of their genes in some regions and not others? Or was the dynamic between Neanderthals and modern humans even so simple as we had come to trust, with expanding African humans absorbing the Neanderthals in a singular event before our cousins’ lineage winked out of existence forever? And is it possible that previously undetected earlier waves of African humans actually contributed genetically to Neanderthals, who, like our own lineage, turn out to be more palimpsest than something immutable and static?

After more than a century, it is clear that our view of our Neanderthal cousins has trod a long and rocky road, as liable to detour into stray cultural fashions and fads as it was subject to being rerouted by hard science. But with ancient DNA and its surfeit of data, the decades of debate about whether Neanderthals were our ancestors has come to a close, replaced by a more informed exploration of their role in our evolution. Now that we know we are all Neanderthals at least at a trace level, the creativity and flexibility of their culture have wrested focus away from titillating depictions of brute Neanderthals as a warped mirror upon our own species. And it’s a compelling topic, even for the most self-interested modern human. Consider that a simple calculation of the quantity of Neanderthal DNA present in modern humans would be equivalent to 160 million pure Neanderthals walking the earth today, more, in fact, than at any other time in the planet’s history. The Neanderthal heyday is long millennia behind us, but who they were precisely continues to matter.

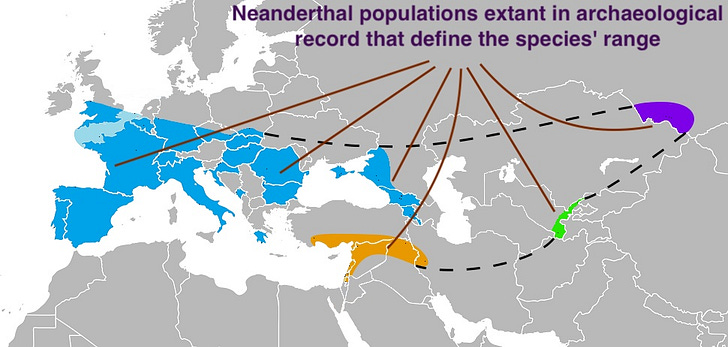

Now, we can agree that Neanderthals were an incredible success story. For over 300,000 years, these heavy-featured humans occupied a vast swath of Eurasia, from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to Mongolia’s Altai mountains in the east. Their southerly range encompassed modern-day Syria and Iraq, and perhaps even Lebanon and Israel. Though the physical characteristics we associate with classic Neanderthals, a robust build, sloping forehead and a massive protruding face, only fully emerged in the past 400,000 years, their lineage’s separation from the one leading to modern humans occurred over 200,000 years prior, when they had not yet diverged from their eastern Denisovan cousins. They were a Eurasian human lineage par excellence, adapted to the Pleistocene’s frigid climes in their stocky compact frames. But they were no aliens, Neanderthals were also Africans like us, albeit scions of a far more ancient migration. And, it now turns out, recipients of migrants from Africa long after their own departure and hundreds of thousands of years before their extinction. Far from an evolutionary dead end, Neanderthals were a grand experiment in surviving the brutality of the Ice Age over hundreds of thousands of years. Traces of that experiment live on in us, the last humans standing.

Reimagining Neanderthals

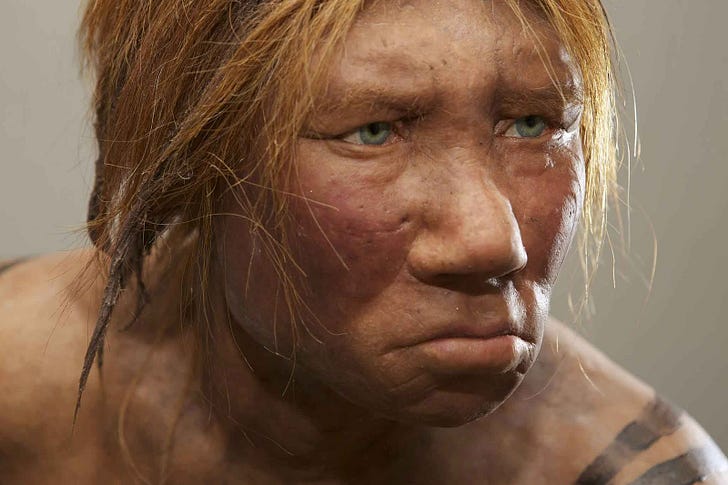

The first mostly intact skeleton of a Neanderthal was discovered at a cave near La Chapelle-aux-Saints, France, in 1908. Judging from the wear and tear on the teeth, scientists assumed this was an older Neanderthal, and decades later it was recognized that he may even have suffered from osteoporosis. Unfortunately, it was this hunched, decrepit individual who served as a model for French anthropologist Marcellin Boule’s reconstruction of Neanderthals; Boule’s interpretation would become an influential archetype in the first half of the 20th century. His Neanderthals were frankly simian: hirsute, slouching and with a gorilla-like mien. This primitive caricature, more missing link than fellow human, persisted all the way into this century. Despite Neanderthal success surviving, even flourishing, over hundreds of thousands of years across a vast territory, many of us grew up regarding them as inferior rough drafts, barely human. The very term “Neanderthal” became an epithet for someone rude, primitive and uncouth. Perhaps the most bizarre instance of our cousins’ dehumanization was Australian filmmaker Danny Vendramini’s contention that Neanderthals were super-predators who actually fed on our own species, a bewildering theory outlined in his book Them and Us. Vendramini’s thesis, put forward in 2009, is the culmination of a line of thought going back to the 19th century; entertainingly, it would by chance be put definitively to bed in the spring of 2010. Neanderthals as animals without speech or creative culture, but simply primates with bestial appetites, is a theory that could only be seriously entertained in a world where their dehumanization was commonplace.

In May of 2010, geneticist Svante Pääbo (who in 2022 won a Nobel prize for his groundbreaking work in the nascent field) and colleagues published A Draft Sequence of the Neanderthal Genome in Science. As detailed in his book Neanderthal Man: In Search of Lost Genomes, this paper was the culmination of a multi-decade attempt to coax into existence paleogenomics, the discipline that analyzes ancient DNA with modern genetic methods. Though Pääbo’s original passion was ancient Egypt, the title of his scientific biography reflects the fact that he will likely be most enduringly associated with the discoveries he spearheaded relating to Neanderthals. A major reason his work on ancient human genomes was so revolutionary is that it overturned a fragile but surprisingly broad consensus that prehistoric Africans (our ancestors) and Neanderthals were fundamentally different. Pääbo’s 2010 data yielded compelling evidence that our own species today retains Neanderthal ancestry. Neanderthal genes are our genes. The differences were clearly not so fundamental so as to keep our two lineages from having the most intimate of relations.

The unassailable facts drawn out of the first Neanderthal genome immediately overturned the earlier orthodoxy that our cousins were evolutionary dead ends. In fact, there had always been those in the field who remained skeptical that we had enough information to conclusively rule out any Neanderthal ancestry in modern humans. Despite these insistent reservations, flashy results reinforcing a version of the Out of Africa model in which Neanderthals were brushed aside from the evolutionary narrative, retained center stage for several decades. The human genome was not mapped fully until the early 2000’s, but in the late 1990’s an earlier team Pääbo led retrieved bits of the Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA sequence and fitted these to a plausible phylogenetic position in the human mtDNA tree. They observed no connection between the newly discovered lineage and any modern haplogroups, seeming to confirm the contention of paleoanthropologists who concluded from analyzing morphological characteristics of fossils that Neanderthals did not contribute to our heritage. Though these genetic data persuaded the statistically naive, theoreticians at the time objected that given the generations that had elapsed between the Neanderthal extinction event and the present, probability dictated that the rare Neanderthal maternal lineages that had introgressed into proto-modern populations had every likelihood of having disappeared along the way by random chance. The same logic that applied to “mitochondrial Eve” also applied to Neanderthals: even if many Neanderthal females contributed genes to modern humans, given enough generations, their mtDNA haplogroups, like the vast majority of prehistoric African human mtDNA haplogroups, were likely to go extinct through random genetic drift (mitochondrial Eve is unique because her mtDNA lineage is the last common ancestor of all the haplogroups that survived this random extinction process).