The Waiting Game: Past, Present and Future of Indian Genomics

Wringing every drop of insight from modern samples, awaiting ancient ones

Some 25% of humanity lives in the Indian subcontinent; neither quite of the Occident, nor of the Orient. This region has played critical roles in the development of human culture. It was from India that Buddhism, the world’s first missionary religion emerged, over two millennia ago. With the Near East and Europe on its left flank and the forbidding Himalayas bounding its northern border, it has remained a well trod byway for the streams of humanity trekking ever eastward toward the planet’s most populous realms, everywhere from East Asia down the Pacific Rim to Australia. In the Age of Augustus, it was in the teeming marketplaces of India’s port cities that merchants from Rome met those from southern China.

But more than just an accident of geography seals South Asia’s global centrality. The nearly two billion modern South Asians are heirs to prolific forebears. In 450 BC, Herodotus noted that the Indians were “by far the most numerous” of the world’s nations. Today, with India having surpassed China in population size, that is again true, though since 1947’s partition between a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan (which, would in turn further calve off Bangladesh), the core nation’s population is far less than if the subcontinent had remained unified (an India with its pre-partition borders today would ring in at 1.975 billion people, versus the PRC’s 1.41 billion). In human prehistory, India’s centrality was a matter of location, and the likelihood that it lies near the nexus of Eurasian humans’ momentous diversification in all directions, at an early step out of Africa.

But in more recent human history, India has played a different role. Its southern location likely made it a refugium for hominins during the cold, dry Pleistocene. And over the last three millennia India has been both a land of wealth coveted by conquerors and a font of cultural wisdom continually reshaping its neighboring civilizations. Indian philosophy influenced thinkers from Athens to Kyoto, everywhere from the abstract monistic philosophies that helped frame Neo-Platonism in third century Alexandria to the Buddhist metaphysics that took root in eighth-century Fujiwara Japan. Meanwhile, India’s wealth repeatedly lured those eager to plunder or tax, from Darius’ Persian armies in the 6th century BC and Alexander the Great in the 4th, down to the Muslim Turks who streamed into the subcontinent after 1000 AD, for gold, greatness and the glory of their god.

For anthropologists, literal scholars of humanity, India stands apart as an absolute goldmine of human diversity, an inexhaustible feast for fieldwork, home to a panoply of richly variegated customs and traditions, where each of thousands of communities maintain their own unique folkways. While China has one official language, the Republic of India recognizes 24 official state languages. In the subcontinent, 25 languages have over 10 million speakers. Hindi alone clocks in at 600 million habitual users with various degrees of fluency, a cool 150 million more humans than can be found on the entire continent of South America. Notably, the subcontinent’s two dominant language families, Indo-Aryan and Dravidian, have extremely distinct profiles, being entirely unrelated genealogically. Though after millennia of proximity, today Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages of course share both features like common vocabulary and phonological quirks like retroflex constants, their syntactical structure and the deepest layers of their lexicons reflect wholly unrelated origins. While Indo-Aryan languages are the easternmost of the Indo-European language family, which dominates Western Europe, and includes the extremely closely related Iranian languages just to the west, the Dravidian languages are entirely unrelated to any languages outside of the subcontinent.

India’s religion and its people recapitulate these tendencies towards complexity and richness already evident linguistically: external entanglement is juxtaposed against deep indigenous particularity. While the subcontinent’s Muslim minority is well known, the Christian minority in broader India number some 38 million, more than in the entire UK. Both these religions are global in scope and universal in ambition, and they of course share the subcontinent with Hinduism, whose Indian connection is, in contrast, constitutive rather than coincidental.

To some extent, India and Indians are Hinduism, and Hinduism is India and Indians. The term Hinduism comes from people indigenous to the land, rather than elevating a great founder or reformer of its beliefs and practices like Christianity or Zoroastrianism (and, rather like Judaism, it is both a religion and a nationality). Before 1772, when East India Company Governor-General Warren Hastings made an explicit linguistic distinction between followers of Islam whatever their ethnicity and adherents of local religions, referring to the latter alone as “Hindus,” the term had generally just applied to anyone of Indian extraction and culture (in other words, Hindus, as opposed to say Turks, Europeans or Persians). We can still readily see how “Hindu” was long a stock ethnic term in North American newspapers of the 19th and early 20th centuries, where mentions of immigrant “Hindoos,” often upon further investigation actually meant South Asian adherents of Islam or Sikhism. Unlike Islam or Christianity, a unified creed did not define Hinduism. Hinduism itself was, and is, a riotous and diverse array of regional cults and Brahmanical philosophies, all threaded together by an unmistakable civilizational scaffold.

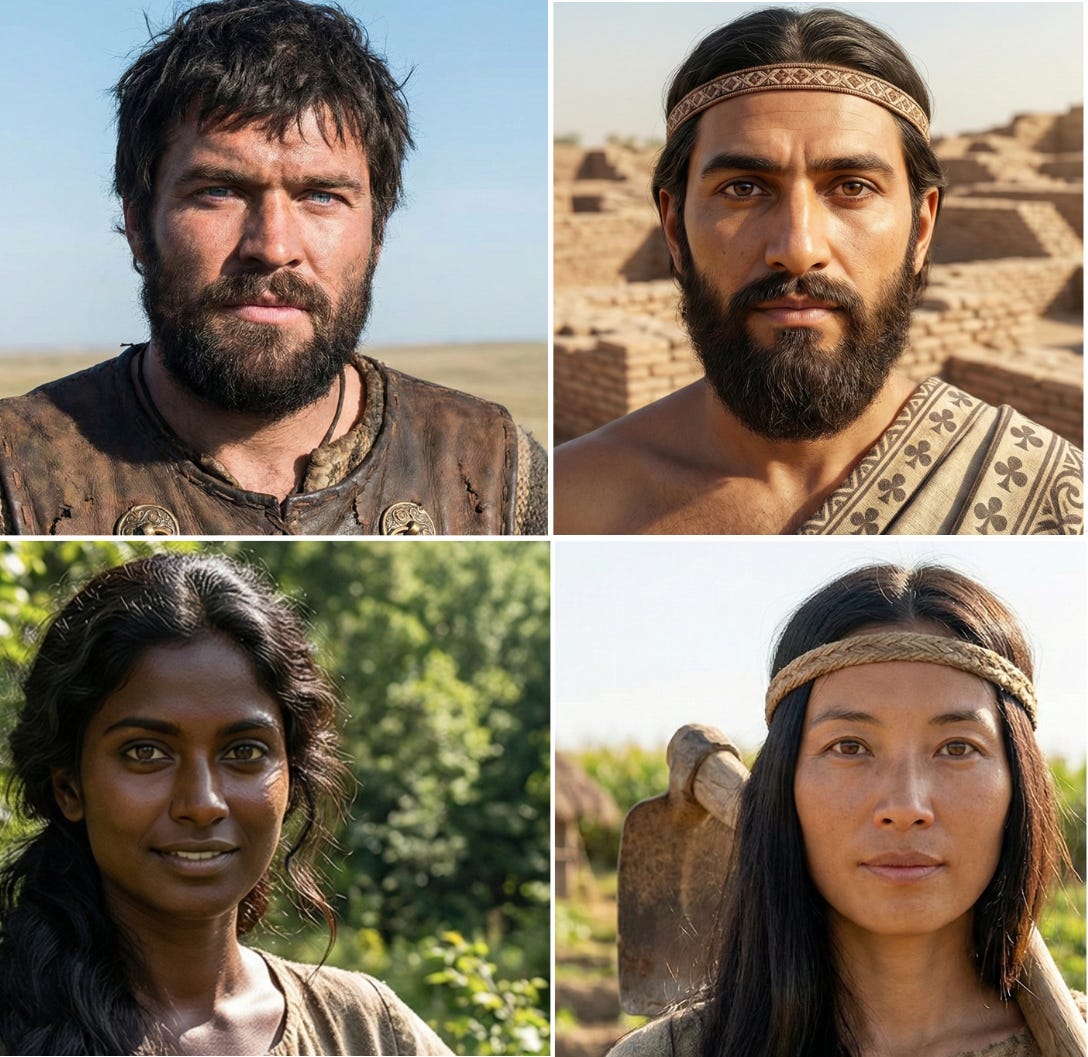

So it comes as little surprise that India’s riotous linguistic and religious diversity also mirrors deep biological diversity. And not just in the biogeographic reality that the northwestern fringe is part of the West Asian climatic and ecological sphere, while most of the rest of the subcontinent is part of the tropics. In the very genetic diversity of its people, India is bewilderingly complex. Iranian-speaking people, whose languages are closer to Persian and Ossetian, occupy the subcontinent’s northwestern edge, abutting the Indo-Aryan dialect zones to their east. Physically, these Iranian-speakers, Pashtuns and Baloch people, resemble West and Central Asians, Kurds, Tajiks, etc. Meanwhile, the subcontinent’s northeastern corner harbors populations who speak Tibeto-Burman, Tai and Austro-Asiatic languages, reflecting deep origins in the lands to the north and east, beyond the mountain escarpments that ring the subcontinent there. But at the core of all this peripheral diversity, runs a broad vein of more formulaic genetic complexity; the vast majority of the subcontinent’s population occupies the “India-cline,” ranging from the Northwest’s Punjabis, dominant in Pakistan and in wheat fields west of New Delhi, all the way to the Tamils of the southeast, busy today erecting gleaming electronics manufacturing plants on what were rice paddies mere decades ago. In keeping with the subcontinent’s diversity, these extremes are very distinct populations, visibility different, but all recognizably South Asian, antipodes of the India-cline.

But what exactly is the India-cline? Over 15 years ago, a scientific research group led by David Reich and Nick Patterson identified this India-cline with then newly-emerging genomic methods. They showed that most Indian populations could be modeled as a mixture between one population (related to Europeans and West Asians), a second, Ancestral North Indians (ANI), and a third, indigenous to the subcontinent, Ancestral South Indians (ASI), very distantly related to Andaman Island natives. Again, biology, like linguistics and religion, reflected both external connections and indigenous roots, with Indians descending from both people related to Eurasians who migrated in during the Holocene, after the Ice Age, and a deeply rooted indigenous component of first people who arrived some 45-50,000 years ago out of Africa.

In further papers published in 2013 and 2019, Reich and Patterson’s group continued refining those models, with the latter paper dropping in time to finally exploit the full force of paleogenetics. In 2019, Vagheesh Narasimhan, while still in Reich and Patterson’s lab, used ancient DNA to demonstrate that ANI ancestry had two components. The major one relates to the lost Indus Valley Civilization (IVC), an advanced early human civilization whose geographical extent was vastly broader than that of either of its fellow groundbreaking contemporaries, Egypt and Sumer. And a minority one comes from steppe pastoralists with ultimate origins on the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea, though the subgroup who arrived in India did so after a sojourn in the forests and marshlands south of the Baltic Sea, where they genetically absorbed the remnants of the region’s last Neolithic people, the Globular Amphora, until it composed 30% of their ancestry.

The ASI too, appear to have been a genetic compound, combining a major component (related to the Andamanese, today an exceptionally isolated population scattered across the Andaman Islands) that has been variously christened “Ancient Ancestral South Indian” (AASI), “Andamanese Hunter-Gatherer” (AHG) or “South Asian Hunter-Gatherer” (SAHG), depending on your paper of preference. Narasimhan’s reading in broad strokes was that between 5000 and 3000 BC, farmers with roots ultimately in northeastern Iran and southern Central Asia moved into the plains of the Indus River Valley, and then later, both southeast into Gujarat and eastward to the limits of the Gangetic plain. These people became the dominant population that eventually gave rise to the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC). Here, between the Indus and Ganges, they absorbed a secondary admixture related to the SAHG. Then, after 1800 BC, with the IVC terminally declining in the face of climatic shocks begun across Eurasia four centuries prior, a wave of pastoralists from the steppe, the Indo-Aryans, arrived. These people further transformed Indian genetics, but especially Indian culture in terms of language and ritual. Indian mythological memory Āryāvarta, the “abode of the Aryans,” was reshaped by these intrusive pastoralists, who in the process wrote their Indus Valley Civilization city-building predecessors out of the narrative.

This was the state of knowledge I wrote about early in 2021, (a first deep-dive post for this substack!) in a two part series. In genomics and paleogenetics today, four years is practically eons; the span between 2017 and 2021 saw orders-of-magnitude gains in our understanding of, for example, Pleistocene Europe, the Middle East and the Americas. After 2020, it was on to other regions; China stepped up, driving their tally of ancient DNA results from 100-200 up into the thousands. The Near East saw the first deep paleogenetic explorations of the Bronze Age. India, meanwhile, saw no progress. In 2021, we had a single 2600-BC genome from Rakhigarhi, an IVC site in Indian Punjab, 38 individuals from Roopkund lake in the Himalayas, dated to two periods, 800 and 1800 AD, and dozens of samples in northeast Pakistan’s Swat Valley dating across 17 centuries, from 1200 BC to 500 AD. And Narasimhan’s 2019 paper included 11 individuals from sites in Central Asia who appeared to bear all or partial subcontinental heritage, probably migrants and traders. He labeled these “Indus Valley Periphery” (IVP).

And now in 2025? Same. Exactly nothing new. The tap has run so dry that China literally releases more ancient Indian DNA than India does itself; a Fudan University lab recently published a study about a 6th-century AD Indian-origin man buried in north-central China. Cremation’s ubiquity across much of Indian history overall has surely hobbled DNA retrieval, but this is not the whole story. Note that multiple Indian labs have teased imminent publication of ancient DNA for years, and then somehow none of these ever materialize.