The Punic Paradox: Genetically, Rome's great African rival was startlingly European

Ancient DNA charts the cosmopolitan Carthaginians’ deep rift between culture and ancestry

Ceterum (autem) censeo Carthaginem esse delendam, "Furthermore, I think that Carthage must be destroyed.” This was the parting phrase with which Cato the Elder consistently concluded his speeches to the Roman Senate in the mid-2nd-century BC lead-up to the Third Punic War. Five decades after the Second Punic War, during which Hannibal had ravaged Italy, only to fall short of conquering it, instead sealing the Carthaginian Empire’s ultimate doom, the city of Carthage itself had nevertheless revived as a vibrant mercantile entrepôt. Its imperial pretensions of previous centuries, when Carthage’s colonies encircled the entire western Mediterranean’s shores, were long gone. But if the Romans were great at war, the Carthaginians’ commercial spirit remained unrivaled. Once intolerant of any military rival in its orbit, Rome now grew jealous of Carthage’s glittering wealth, which continued to wax even in the persistent shadow of the ascendent Roman Republic.

In fact though, Carthage’s greatness long predated that late 2nd-century Indian summer in Rome’s shadow; but since the Punic people did not birth a successor civilization, its genuinely deserved reputation among the ancients can only be pieced together from others’ stray observations. For example, buried in Greek archives lies a 101-line translated record of a 5th-century BC voyage originally authored by a Carthaginian navigator named Hanno, scion of the city-state’s most prominent family of that day. The text bears testimony to Carthaginian maritime audacity in the centuries before their Mediterranean-wide conflict with Rome, as their fleets flew past the frontiers of the known world.

With a flotilla of 60 ships, Hanno voyaged beyond the Pillars of Hercules, founding several cities along the coast of today’s Morocco. Eventually the fleet encountered “Ethiopians,” which almost certainly means that Hanno reached sub-Saharan Africa, pushing southward along the Atlantic coast. Finally, the passage references journeying into lands with volcanic mountains and gorillas whom they identified as “hairy men.” The Carthaginians killed some of these latter, taking their hairy pelts back to Carthage, where they remained on public display until the city’s destruction in 146 BC.

The scholarly consensus seems to be that Hanno and his fleet pushed at least to modern day Senegal, though many argue that the description of a volcanic mountain more closely fits Mt. Cameroon, while gorillas only range much further eastward in Africa, beyond modern Nigeria as the coast begins to steer south toward the Congo river. While Hanno’s fleet dramatically reset the limit of the southern frontiers known to Mediterranean peoples, Himilco the Navigator led other Carthaginian ships northward, likely establishing contact with the peoples of Britain four centuries before Julius Caesar would, first securing consistent trade routes to bring precious Cornish tin to the Mediterranean market.

Hanno and Himilco’s voyages occurred at the beginning of the Carthaginian Age in the western Mediterranean, more than two centuries before the First Punic War. In 535 BC, Carthage’s navy defeated forces marshalled by the Greek colony of Massalia (modern Marseille) near Corsica, while a subsequent 509 BC treaty with newly republican Rome ceded to the Punic power the seas of the western Mediterranean beyond Italy’s shores. In the next century, Carthage’s armies repeatedly crossed over from North Africa into Sicily, conquering the western half of the island, subjugating its numerous Greek-speaking cities. By the early 3rd century BC, Carthage held sway over the North African coast to its west, and had established colonies and possessions across the Mediterranean in Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and all along Iberia’s eastern coast, as well as establishing hegemony eastward along the North African coast toward the edges of Egyptian domains.

Carthage’s appellation at this time was “ruler of the sea,” and its trading empire extended both to the farthest western limits of the ancients’ known world, beyond civilization’s edge, and back eastward, as its magnificent “silver fleet” routinely arrived to disgorge wares in Egyptian ports, in the Phoenician motherland, as well as in Greek trading hubs like the southern Italian port of Taranto. Poised at the junction between the western and eastern Mediterranean, in 300 BC, the city of Carthage possessed both an empire and a stranglehold on any commerce that traversed the network of sea lanes. Its prestige was such that the storied Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, founded by one of Alexander the Great’s most successful generals and fated to only end with glamorous Cleopatra’s ascendence, even chose to feature the Phoenician horse symbol associated with the Punic power upon its own coinage. In the decades before the first hostilities between Rome and Carthage, the latter city was the populous one, with half a million inhabitants, a cosmopolitan nexus of trade brimming with more humanity at its peak than Athens, Syracuse or even Alexandria.

Up until the Third Punic War began, long past Carthage’s apogee, the city remained a bustling nexus of trade. This dynamism was completely obliterated, and with it was swept away any memory or record of probably additional centuries' worth of audacious voyages into the barbarian realms to the north and south. While Rome’s advances were accomplished piecemeal, methodically, their Carthaginian antagonists seem more to have proceeded by the seat of their pants, stitching together a far-flung empire via risk-taking commercial forays, streaking across the seas, the society’s progress driven by profit-minded merchants rather than an ambitious general’s quest for bloody glory.

Hannibal’s defeat two generations prior, in the Second Punic War, ended Carthage’s imperial dreams, as a triumphant Rome stripped it of all its colonies, absorbing them into its own burgeoning portfolio. What was an extensive Punic commonwealth that had ringed half the Mediterranean was reduced to a rump, just Carthage and its near hinterland. But within a few decades, even this proved too much for Rome, which concocted a casus belli, and then crushed the token Carthaginian resistance. The citizens of the merchant-city were killed, scattered or enslaved. The once dazzling Carthagian capital of great defensive walls and magnificent public buildings was utterly erased, preserved only in the memories of its Roman enemies.

Though Carthage would reemerge as an urban center again more than five decades after its obliteration in the Third Punic War, one last time rising as a great city of western Mediterranean antiquity, that late incarnation was a new city built atop the ruins of the old. And yet, though the political power and military glory of the old Carthaginians faded to faint historical memory, a matter for annalists and a morality tale for rhetoricians, the Carthaginian cultural legacy continued on in language, religion and folkways. Septimius Severus, a Punic-descended Libyan born in the colonial Carthaginian city of Leptis Magna near modern Tripoli, became Roman Emperor in AD 193. And St. Augustine of Hippo in the early 5th century AD, more than 550 years after Carthage's destruction, records the presence of Punic speakers in the North African countryside.

Much of what actual precise detail we know of Carthage we glean from the extensive works of contemporary 2nd-century BC historian Polybius, who chronicled the wars between the North African city-state and Rome from 264 to 146 BC. For the Romans, Carthage’s rise and fall served mostly as a testament to their republican virtues, a foil for their fortitude in the face of repeated wars, a vivid proof of their ability to overcome oriental avarice and opportunism. But however little recorded, the city-state’s legacy is far richer, and extended long after its jealous rival’s ultimate victory.

Carthage and its culture shaped Mediterranean history for 1,500 years, from the city’s 9th-century BC founding to North Africa’s last centuries under the Roman Empire as the forces of Islam closed in. Rome ultimately won and wrote the histories, but before its defeat, Carthage had already left an indelible imprint as one of the Mediterranean’s preeminent powers, a juggernaut of undeniable political, military and mercantile achievement centuries before Rome’s consolidation of Italy. Even after the Carthaginian homeland’s absorption into the Roman system, the Punic language had already sunk deep enough roots in North Africa to persist as a rural tongue, with Christian priests still preaching in Punic under St. Augustine several centuries after they had abandoned their old pagan religion.

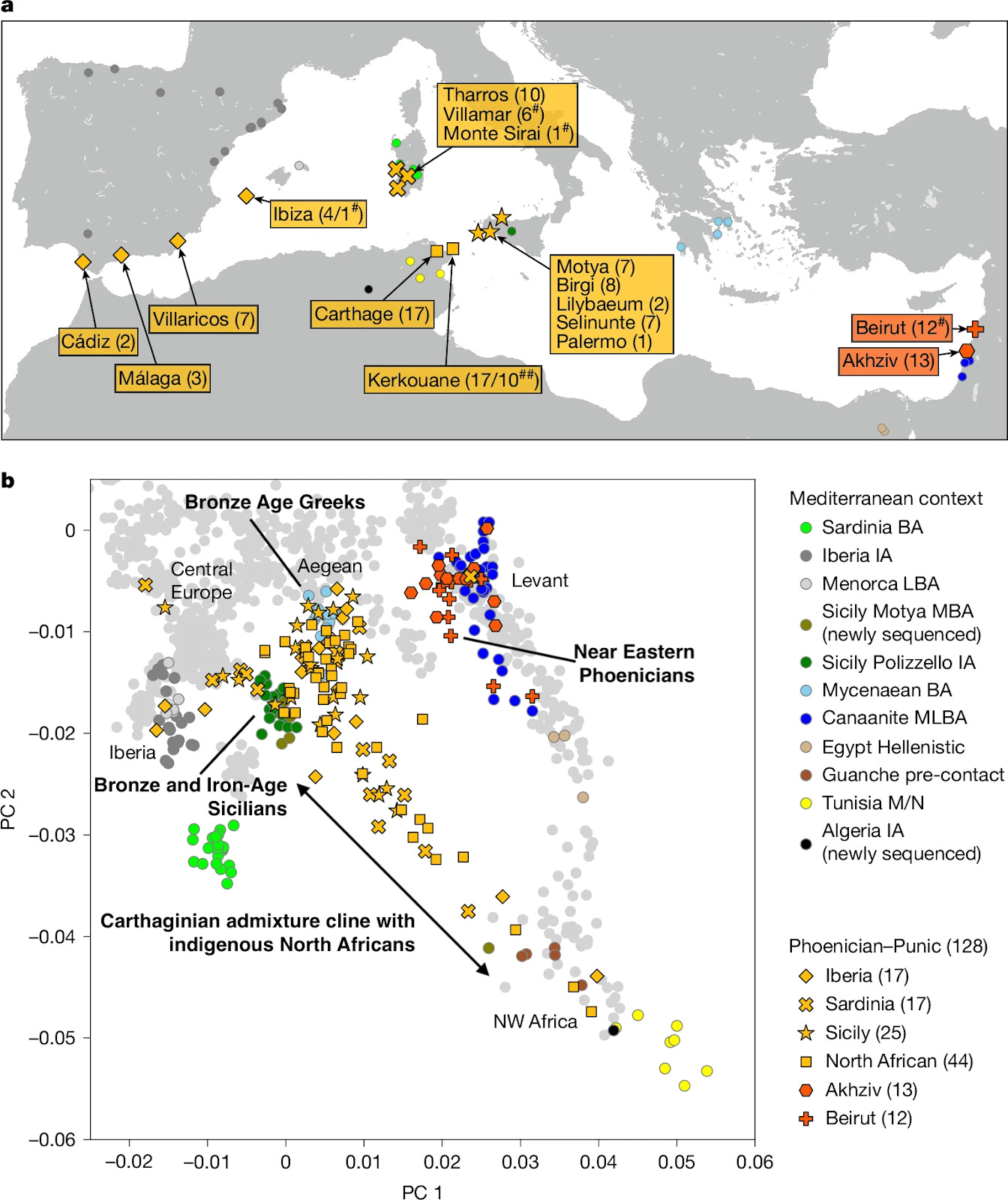

And now, paleogenetics has revealed a new twist to this cultural resilience: it emerges that the Carthaginians who fought Rome for over a century in their extended cycle of pan-Mediterranean wars were overwhelmingly not actually descended from the original Levantine settlers who had emigrated from old Phoenicia. Instead, even the pre-Roman-era people of Carthage were predominantly of the same stock as southern Italians and Greeks (with a reasonable leavening of North African Berber stock, given Carthage’s geographical location west of Egypt). Though they spoke a Canaanite Semitic language related to Hebrew (and more distantly to Arabic), and worshipped pagan Semitic gods, the Carthaginians who spent five generations skillfully resisting and retaliating against the waxing belligerence of an ascendant Rome overwhelmingly prove to have been solely cultural heirs to the Phoenicians, not actually their biological descendants.

We know that voyages embarked out of the late-Bronze-Age Levant, when trade networks linked the western and eastern Mediterranean in the centuries before 1000 BC. The cities of the maritime Levant in the shadow of the Lebanon mountains seeded their identity, their understanding of the gods and the languages spoken along shores of the Mediterranean, among their far-flung Punic colonies. But their legacy of blood diminished over the generations until it was the faintest trickle by the time of Imperial Carthage. Carthage, and the Punic culture that was Phoenicia's legacy, embody cultural imperialism in its purest form, and its adopters wholly subsumed themselves into their newfound identity, overwriting their own ancestral traditions, a fact that would only be uncovered millennia later with ancient DNA.

To the seas

Carthage’s origin story as recorded by Greek authors has Queen Dido founding the city in 814 BC, with the name Carthage coming from Qart-hadasht, or “New City” in Phoenician. Dido was fleeing political turmoil in her home city of Tyre, which lies in modern-day coastal Lebanon. Though Dido’s tale clearly belongs to a topos of fictional founding myths, key actors within the narrative seem to correspond to real historical figures. Dido’s grandfather, Balazero, is likely Baa‘li-maanzer, a king of Tyre, historically recorded as paying tribute to the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in 841 BC. Whatever the legend’s actual veracity, the earliest evidence of Phoenician archaeological items in the environs of Carthage dates to the 9th century BC, in line with the ancient authors’ dates for Dido leading a migration out of Tyre.

But this emigration was part of a centuries-long process that saw Phoenicia rise as an independent power in the Near East. At the height of the Late Bronze Age, before 1200 BC, Phoenicia and the city-states of the Levant were catspaws in the Egyptian, Hittite and Assyrian Empires’ geopolitical machinations. They served as centers for trade and diplomacy, their hinterlands’ cedar forests meanwhile feeding shipbuilding and construction’s appetite for lumber, particularly in wealthy Egypt. But with the great states’ collapse after 1200 BC, the key cities of the coastal Levant, Tyre, Sidon and Byblos chief among them, became independent mercantile powers. Collaborating with the United Kingdom of Israel, the region’s paramount land power, Phoenicia's coastal cities drove an early Iron-Age economic renaissance powered by voyages of exploration in search of wealth. The Bible, describing King Solomon’s reign, relates that:

For the king’s ships went to Tarshish with the servants of Hiram. Once every three years the merchant ships came, bringing gold, silver, ivory, apes, and monkeys.

Tarshish here refers to the kingdom of Tartessos in southwest Spain, inland from the Straits of Gibraltar, and Hiram was a 10th-century ruler of Tyre. This underscores that in the century before Carthage’s founding, Phoenician trade networks already extended to the Pillars of Hercules. And the importance of faroff Cornwall’s tin mines for the smelting of bronze reflects how long bustling trade networks had already stretched from the great cities of the Near East, up the Atlantic seaboard.

With the end of the Bronze Age imperial order, a chaotic collection of entrepreneurial city-states sent traders and colonies outward, to the Mediterranean’s very limits. Their frenetic decentralized forays replaced a previous regime of staid royal-sponsored interchange conceived more as gift exchanges to nourish diplomacy between potentates than the grubby hustle of trading houses. Even a casual reader of historians like Herodotus and Thucydides will know that ancient Iron-Age Greece colonized Sicily, southern Italy and southern France. Sicily and southern Italy were Magna Graecia, and Athens’ attempted invasion of Syracuse illustrates that this western extension of the Greek world was always seen as an integral part of Hellenic geopolitics. But the Greeks were latecomers, their primary period of colonization dating to 750 BC and after. The Phoenicians, from whom we have far scantier records, seem to have begun their explorations centuries prior, expanding not just in North Africa, but to Spain and Sicily as well. Cádiz, Palermo and Malta all retain Phoenician roots.

But Carthage, near modern-day Tunis, was the greatest of antiquity’s colonies, even going on to seed its own urban progeny, like Cartagena in Spain and Marsala in Sicily. It was the jewel in the crown of Phoenicia's expansive cultural empire, which had become a veritable Punic forest towering over the modest original grove of Levantine cities, Byblos, Sidon and Tyre, which lay in a string just 100 kilometers long. And yet new genetic evidence suggests that while Carthage’s cultural roots were indisputably Levantine, at its imperial apogee, from 400 BC, when it had already dispatched both Greeks and Etruscans, all the way through the storied long century of Punic Wars that roiled the Mediterranean until 146 BC, its Near Eastern demographic foundation was already buried so deep beneath a new genetic superstructure that the signal was almost entirely lost.