The haplogroup is dead, long live the haplogroup! (part 2)

What mtDNA and Y-chromosomal lineages can still tell us

Note: Part 1

Though science aspires to uncover eternal truths, its practice remains historically bounded. A couple of decades ago, a peculiar confluence of biological realities, technologies and methods coalesced to drive uniparental lineages to prominence. First, mtDNA is particularly copious because each human cell has 1,000 to 6,000 mitochondria (as opposed to one nuclear genome). So before polymerase chain reaction techniques enabled the amplification of even minute quantities of DNA in the 1990’s, mtDNA was targeted because it was easy to obtain. The original mtDNA work that led to mitochondrial Eve even relied on collecting discarded tissue-rich placenta which is both an abundant and accessible source of genetic material. But even after PCR’s advent, sequencing technologies were laborious and expensive. And further, mtDNA was known to have a hypervariable region that was rich in genetic information and accumulated mutations (ever-informative markers) faster on the evolutionary time scale. So mitochondrial DNA did not fall out of fashion even as other genetic techniques joined it in demographic inference.

Though the Y chromosome had fewer innate advantages than mtDNA (it was much harder to extract sufficient quantities and samples did not have as much variational density as mtDNA), it was poor in functional genes and thus assumed not to be strongly shaped by natural selection, making it a perfect tracer for demographic history. The Y, like mtDNA, records how you relate to others, not how you adapt. Finally, as we’ve covered, neither marker recombines, meaning that they were very tractable for modeling on the computational platforms of a generation ago (imagine a brace of the garish blue iMacs circa 2000 all set up in parallel). Y and mtDNA lineages were literal trees that converged on a single point in the past, not reticulating lattices, and coalescent theory meant every step backward there were fewer and fewer branches to track.

The successes and pitfalls of the uniparental age

But sometimes opportunity can be a curse. Historical population geneticists twenty years ago got caught in the trap of looking under the lamppost. Researchers were deeply interested in complex questions, but the first tools at their disposal, Y and mtDNA family trees, proved inadequate for their ambition.

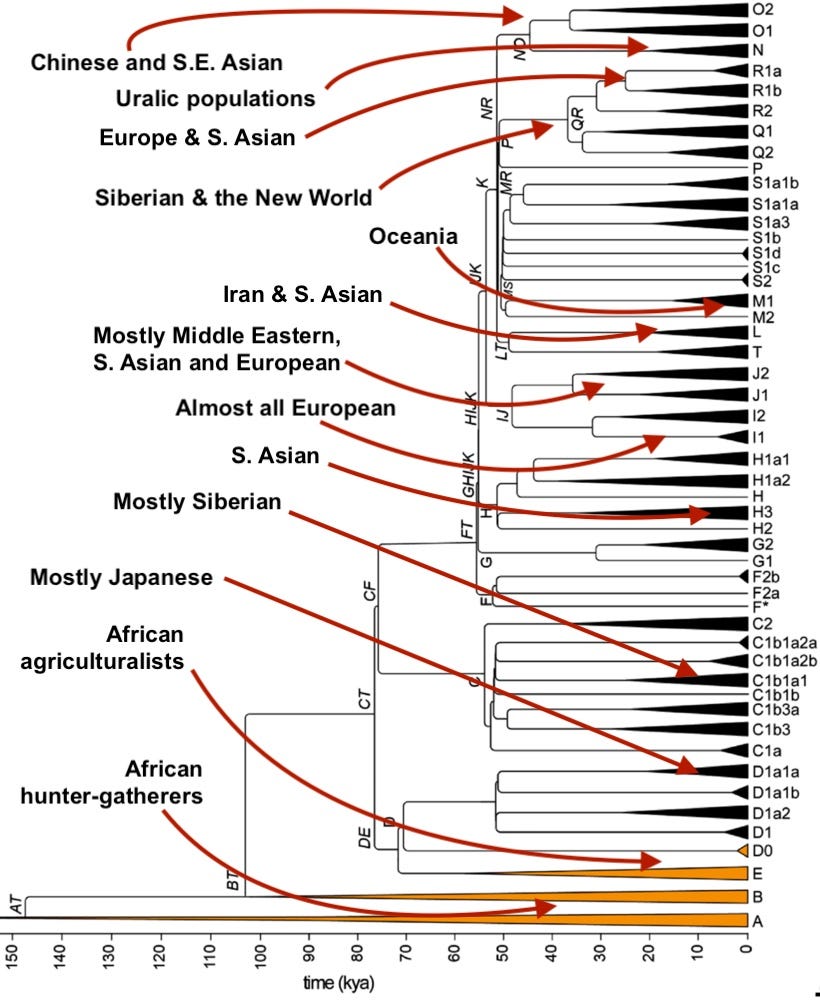

As we’ve seen, mtDNA and Y trace only a single direct line of genealogy, while the sum of any population’s demographic history is almost always a complex bramble. This limitation can be illustrated sometimes even by the contrasting mtDNA and Y narratives within the same population. The Munda tribes of east-central India speak a language that seems distantly related to Cambodian. Although, if you only had their mtDNA haplogroups to examine, they are a perfect 100% match with their Indian neighbors. Given that, you might reasonably dismiss their linguistic difference as just reflecting cultural diffusion. But if you were able to look at their Y-chromosomal lineages, you would find that 65% of them are clearly Southeast Asian in origin, not Indian (haplogroup O, a lineage very rare west of Burma). The two lines of DNA, maternal and paternal, tell very different stories, the stories of two entirely distinct peoples who eventually braided their heritage together into a new population.

With the New World’s mixed populations, we are well aware of the history, so upon confirming that the mtDNA haplogroups of Argentinians are about 50% indigenous we aren’t at much risk of fallaciously concluding Argentina is half-indigenous by ancestry. We realize that generations of male-skewed European migration have yielded a mostly European-heritage population whose mtDNA lineages nevertheless reflect the scarcity of European women among the early waves of migrants.

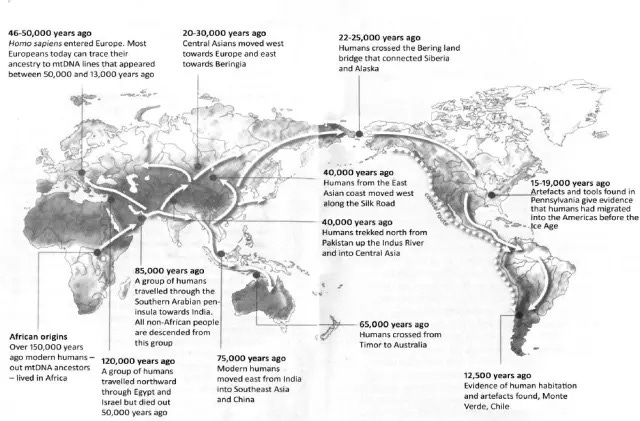

A second problem was that works of historical inference using only contemporary geographical distributions of Y and mtDNA haplogroups rested on a tacit premise that migration generally defined the early phases of human expansion. And that it was followed by a settled period in relative stasis. This assumption was sometimes made explicit; for example, Stephen Oppenheimer’s 2004 book The Real Eve: Modern Man’s Journey Out of Africa, featured an mtDNA phylogeny overlain on a map of the world (above), depicting the planet’s sequential, colonization during the Pleistocene, from Africa to Eurasia and finally on to Australasia and the New World. Each mother would settle in a frontier zone, and her daughters move onward in the next generation, producing an mtDNA genealogy where genetic, historical and geographic distances were perfectly aligned. In unfurling the genealogical tree, Oppenheimer proposed to read human history in the branching patterns displayed.

Alas, the basic assumption that mass migration and population turnover largely cease once people reach a particular territory in prehistory seems to be false. This is not a problem exclusive to uniparental lineages; the same oversimplification plagued genome-wide analyses when they became ascendant.

And once you go beyond simple dynamics of rapid population expansion and replacement (the Out of Africa migration or the replacement of European hunter-gatherers both fit that bill), uniparental markers could lead you astray or preserve no record at all of more modest demographic shifts. In contrast, the rich, dense data offered by genome-wide analysis over hundreds of thousands of SNPs delivers innumerable phylogenetic windows on a population’s history, as opposed to just two, and could anticipate ancient-DNA outcomes in ways far beyond Y and mtDNA’s power. David Reich’s 2009 paper Reconstructing Indian Population History used modern samples on genome-wide data to broadly predict the results of 2019’s The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia, which utilized actual ancient DNA samples).

Finally, there is the problem of time depth and information loss. Because Y and mtDNA lineages are passed through only half the human population, they are subject to stronger genetic drift and lineage turnover. When probing the deep history of our species, we can’t get back past the most recent common ancestor ~200,000 years ago, since both Y and mtDNA are blind beyond this genetic singularity when all extant lineages converge into one. This is a problem because our Neanderthal and Denisovan cousins diverged from us more than 500,000 years ago. We now know that there is both Denisovan and Neanderthal admixture in modern humans, but neither Y nor mtDNA research based on modern human phylogenies ever gave us an inkling of this reality. These single markers simply lack the broad power to bring into focus our species’ more subtle long-term evolutionary dynamics, because of their narrow time horizons and limitation to only a single line of genealogy.

So if they were inadequate in so many ways, why do I bring up uniparental lineages in every human population story I tell today? Because, even in that Icarus stage when the field was trying to make these targeted tools be all things to all people, not every sally was a dead end. And the successes illustrated the unique strengths of the markers in specific contexts, when the evolutionary forces were so pervasive that a single lineage was sufficient to capture demographic history, or when mtDNA’s ease of extraction made it the best choice for degraded samples. Simple and elegant uniparental analyses often returned results that would later be confirmed by more complex methods once orders of magnitude more computational resources and sequencing data came online.

The persistent relevance of mitochondrial DNA was underscored when in 2010 it was retrieved from Neolithic sites in Europe, and the shocking results prefigured what more thorough genome-wide ancient DNA would subsequently confirm: Europe’s first farmers were like no other population alive today; between 8000 and 5000 years ago the continent was almost entirely dominated by a people of mostly ancient Anatolian ancestry, untouched by the migration from the steppes to the east that would wash across the continent over and over after 3000 BC. Only the inhabitants of Sardinia maintained their Neolithic character in the isolation of their island, being impacted by outsiders only after 1000 BC, and even today carrying the greatest proportion of farmer ancestry in Europe.

Haplogroups as scouts and tracers

With the benefit of hindsight, now we can see that much of the work of interpreting distributions of haplogroups twenty years ago might as well have been reading tea leaves. Uniparental lineages just didn’t offer enough information on their own to configure fine-grained narratives robust to future plot twists and discoveries. Within a few years, powerful new techniques would muscle them offstage almost entirely.

But by then, dramatic “theories of everything” based on a Y or mtDNA phylogeny alone had been propounded in popular press books and documentaries (Bryan Sykes’ 2006 Blood of the Isles was in fact only based on a bit of the blood of the Isles). Historical geneticists used Y chromosomes and mtDNA to argue that modern Europeans descended from Pleistocene hunter-gatherers, which proved to be spectacularly wrong, as the hunter-gatherers left almost no genetic legacy (this is incontrovertible now that we can compare ancient to modern DNA). And on the Indian subcontinent, prehistorians ignored 20th-century biological anthropological theories based on physical appearance that argued South Asians were a mix of West Eurasians and indigenous populations of much longer residence. Resistance to the idea of recent mass migration by archaeologists and philologists was less about the theory’s merits than the idea’s association with German nationalists like Gustaf Kossinna, who had laid the groundwork for elements of Nazi anthropology. Today we know that the older anthropological work was mostly correct on India (to be fair, there were minority voices in genetics that remained open to migration and admixture). Finally, although geneticists relying on mtDNA correctly adduced that Native Americans were related to the populations of East Asia, they entirely missed that 30-40% of their ancestry was from a Paleo-Siberian population (“Ancient North Eurasians”) with closer affinities to Europeans.

And yet again, this is not to suggest uniparental lineages were useless. Both mtDNA and Y-chromosomal phylogenies root modern humanity’s origins within Africa, supporting the dominant interpretation of the fossil record and genome-wide analysis over the last twenty years. And, when integrated within a broader disciplinary perspective, they can be quite helpful and clarifying, even contributing the decisive clue in a complex case. Y and mtDNA haplogroup affinities make it clear that Latin Americans are a mixed population where paternal and maternal heritages differ, with the former from Iberia and the latter indigenous to the Americas. Y chromosome haplogroup Q among indigenous people in North America and in Eurasia was a hint of deeper connections between these populations (later, confirmed with the discovery of Ancient North Eurasians, or ANE). On their own, these uniparental lineages were inexplicable, but they have since become entirely comprehensible (dominance of Y chromosomal Q also gives away that ANE heritage in Native Americans is strongly male-skewed).

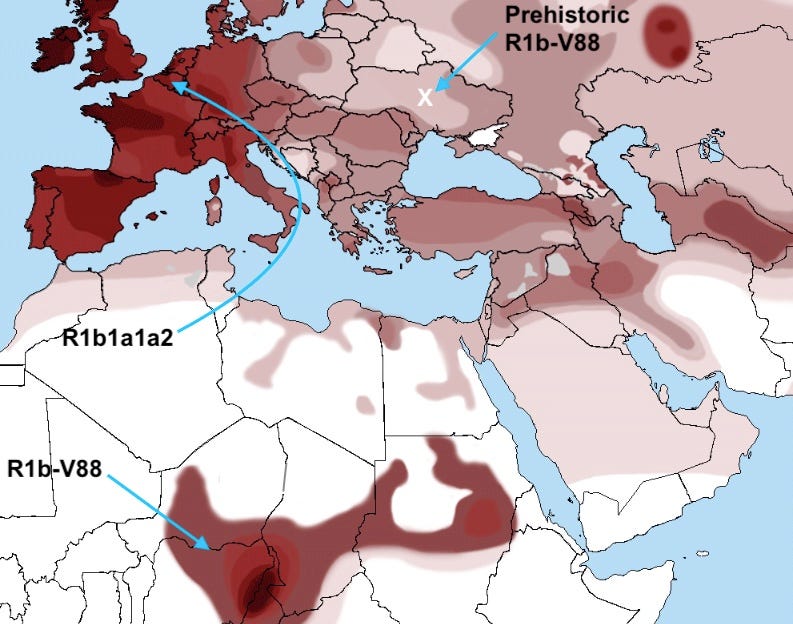

So where is it that uniparental lineages now seem to contribute most? Let’s look at a few good cases. One key use is flagging possible avenues of inquiry. Consider that for twenty years a detail of the R1b lineage’s distribution has presented a mystery: why does a region around Lake Chad have such a high frequency of this ordinarily West Eurasian haplogroup? Ancient DNA tells us that Western Europe’s high R1b frequency is a feature of the last five millennia of migration. The R1b variant present in Africa, R1b-V88, is distinct from its supernumerous European cousin, and the two branches seem to have diverged more than 5,000 years ago. Today, using genome-wide analysis, researchers have confirmed a millennia-old Eurasian migration into Central Africa, so the distribution within Africa is no longer such a mystery. But where exactly did R1b-V88 arrive from? Ancient DNA can answer that question; it seems to originate in prehistoric Ukraine. A deep and thorough genome-wide analysis of the small Eurasian fraction in Chadians might have yielded this result at great cost and effort, but the precise information conveyed by the Y haplogroup was an accessible early shortcut to the truth.

In a best-case scenario, you’re always lucky enough to have a high-quality whole-genome at your disposal. With it, you can reconstruct population history incredibly reliably. Reality is often messier and necessitates creatively applying any tools that can be marshaled. Last year saw a paper published on the ancient DNA of the Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture that flourished in western Russia north of the Pontic steppe 4,500 years ago. Looking across whole ancient genomes, the authors found that this population was almost a perfect match for the contemporaneous Corded-Ware-culture samples from further west, a culture that began in Poland and expanded westward into modern Germany and Scandinavia. Historical linguistics has examined the names of the rivers in the region of western Russia where the Fatyanovo-Balanovo flourished, and surmised that they may have been named by speakers of a Baltic dialect (from which modern Lithuanian and Latvian descend). But in terms of genome-wide admixture, the authors couldn’t reach any specific conclusion about affinities. So, they looked at the uniparental markers. Many individual males in the burials represented haplogroup R1a, which is prevalent today among speakers of Slavic and Indo-Iranian languages (with smaller fractions among Germanic and Baltic groups). Among the samples with adequate data, six had the Z93 mutation of R1a. This is almost always associated with Indo-Iranians, so the uniparental markers allowed the researchers to conclude that the Fatyanovo-Balanovo society was one of the earliest precursors to Indo-Iranian populations that expanded eastward, and eventually south, over the next 1,000 years. Given a bunch of Y-chromosomal lineages in isolation without the assistance from archaeological, linguistic and genome-wide context, the case would be far thinner. But it’s not 2000 anymore, and questions of prehistory can be approached today from countless angles, yielding a sharp stereoscopic picture, ever more impervious to distortions and weird visual artifacts.

Closing the circle

A generation ago, genetics had come inconceivably far; the combination of vastly more powerful molecular techniques (like PCR amplification and ancient DNA extraction), precise far-sighted analytical frameworks (coalescent theory) and the concrete horsepower of computation yielded a rich informative forest of phylogenetic trees planted atop Y-chromosomal and mtDNA data. Using these new tools, researchers established distinctions between numerous species, and confirmed the African origin of all humanity. Next, they drilled down at a finer scale and established continent-wide differences in macro haplogroups (if your Y haplogroup was R, you probably were not East Asian, if your mtDNA haplogroup was U5, you probably were European). But like Icarus, they soon outran the power of their techniques and ended up lost in ad hoc and unfounded pattern matching. In the second half of the aughts, genetics stepped away from the proverbial lamppost of Y and mtDNA haplogroups, and into genome-wide studies’ blinding klieg lights, where genetic relationships across thousands of markers could be clearly illuminated. And finally, after 2010, ancient DNA began to yield real genetic data from the past, rather than conjectures and inferences. It was as if the sun had come up and we could now conduct all our research in full daylight, rather than twilight’s dregs.

But uniparental markers remain key to understanding the histories of our forefathers and foremothers, back to the beginning. Because of their sex-biased inheritance, Y and mtDNA quantify the brutal reality of prehistoric conquest. Comparing Y and mtDNA allowed geneticists to conclude that 4,000 years ago, a few paternal lineages engaged in massive polygyny across Eurasia (coinciding with the spread of Indo-European languages). The combination of ancient DNA and uniparental markers have now shown that Neanderthal Y chromosomes and mtDNA are actually closer to modern humans than to their Denisovan cousins. Even high-quality whole genomes from Neanderthals and Denisovans do not present the clear results of ancient modern human admixture into Neanderthals that uniparental markers offer.

Uniparental markers are often very useful in getting a handle on fine-grained details, building on genome-wide evaluations of the human demographic past. In some cases where there is an archaeological turnover without a concomitant genome-wide shift, Y and mtDNA lineages can still detect changes. This is the case in Northern Europe, where the Nordic region saw multiple migrations from the south over 1,000 years. These were detectable archaeologically and with Y chromosomes, but not through other genetic analyses. In 2800 BC, migrants descended from the Corded Ware Culture of Eastern Europe arrived in Scandinavia. Genetically they were about 75% steppe heritage, with the rest being Central European farmers assimilated just after the nomads left their Pontic homeland. Like other Corded Ware groups, the men among the newcomers were all of the R1a Y haplogroups. But after 2500 BC, R1a was abruptly replaced by R1b, indicating paternal lineage replacement, likely due to Bell-Beaker expansion from the southwest. But the overall genome looks very similar, because Bell Beakers descend from a western Corded Ware population. Then, after 2000 BC, the frequency of haplogroup I1, which remains the dominant lineage in modern Scandinavia, rose sharply, indicating another ethnolinguistic shift with the onset of the Nordic Bronze Age. Again, this is only discernible with Y chromosomes, because the overall genome-wide ancestry did not change. On their overall genome, modern Scandinavians look roughly like descendants of Corded Ware and Bell Beaker populations, but the Y chromosome tells a more detailed story. This is a classic instance where all our genetic tools are worth applying to these questions because our understanding is incomplete without all viewpoints.

In a way, over the past generation, we’ve come full circle on uniparental markers. When they first made waves more than a generation ago, phylogenetic analyses of mtDNA and Y chromosomes were transformative and culturally impactful, with television documentaries heralding the discovery of both mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam. Tackling big questions in concert with paleoanthropology, uniparental population genetics got out of the blocks fast, correctly establishing the overall shape of modern humanity’s emergence. The issues began when researchers got even more ambitious, tackling complex questions too grand for these targeted, precision tools. The powers of our one-time wunderkinds were stymied by both what we now know were faulty basic assumptions about minimal migration after initial expansions, and the inherent limitations of a vanishingly narrow thread of heritage wending back through the millennia.

Though uniparental markers still proved useful in estimating things like how many offspring Genghis Khan may have sired, by the 2000’s it began to feel like more misses than hits. But that was then. Although uniparental ancestry answers questions over a glacial time scale, the field of paleogenomics itself can at times feel like it morphs at light speed. Y and mtDNA analysis have long since been joined by deep surveys of whole genomes of modern people and an enormous wealth of ancient DNA analyses. So now, instead of overpromising or building ambitiously upon shaky assumptions, modern Y and mtDNA phylogenetics have found their role as essential accessories to the overall toolkit of next-generation sequencing, as well as complementing the burgeoning field of paleogenetics.

The uniparental markers, mtDNA and Y chromosomes never belonged on the marquee where they briefly featured at the turn of this century. But as the field of paleogenomics continues to mature, they keep turning in brilliant cameos in the sprawling saga of our species. Given that even human cell teems with mtDNA and Y chromosomes are carried by every human male, the plotlines of haplogroups are literally the stories of us all, of our human race. In subsequent posts, I will begin to unravel the tales of some of our most storied haplogroup lineages.

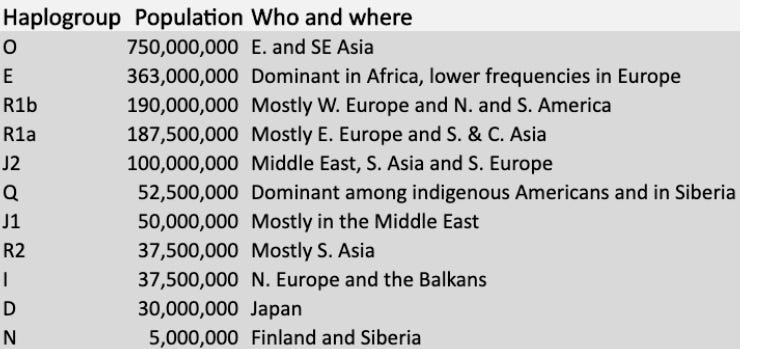

In the table below, you will find the 11 most numerous Y-chromosome haplogroups extant among humans today. If you or your family carries a rarer Y-chromosomal haplogroup, I’ll leave the comments open to all so you can feel free to name it. (Notably, Y-chromosomes have historically been more obsessively studied, in part because they are more starkly geographically segregated than mtDNA haplogroups)

Based on what I’ve read before, you believe Y-DNA H in India is associated with the Iranian agriculturalists, correct?

Do you think it could possibly be AASI instead, and what makes you lean towards one belief over the other?

What is the chart implying about the migration path of R1b1a1a2? Did it reach Western Europe via North Africa?