The haplogroup is dead, long live the haplogroup! (part 1)

Why mtDNA and Y-chromosomal lineages matter

Note: part 2

In every regional or population history I write, you find references to Y-chromosomal and mtDNA “haplogroups.” While never quite the central focus of the story, they’re not exactly ornamental trivia either. Haplogroups come with abstruse nomenclature, letter and number combinations of unpredictable length. But on the plus side, their relationships to one another can be visualized as literal treelike schematics. And they lend themselves to narrative structures we’re all at home with; being able to say that “R1b and R1a are ‘brother’ haplogroups” paints a clearer picture for most readers than when I assure a colleague “a ‘ghost population’ added to the model resolves the f-statistics in the population graph.” Haplogroups are useful signposts, but in an era of ubiquitous GPS, perhaps they’re a bit more like precious fragments of early maps at the historical society than precise satellite coordinates.

Y and mtDNA studies were the genomic darlings of the turn of this young century, but the bloom is off as we hurtle deep into a post-genomic era. Is there really any point to these flimsy little tendrils of genealogical arcana now when all three billion human base pairs can be routinely illuminated? Paradoxically, no longer being overexposed stars of the show has freed up Y and mtDNA markers to meet their full, unique potential in the complex narratives of historical population genetics. They never made sense as matinee idols. More like scene-stealing character actors, they have finally come into their own when tapped to shed light on different demographic histories of the sexes due to culture (polygyny or polyandry) or conquest (capture of indigenous women) or precisely trace high-status lineages across time. Today these exceptional tools finally have a worthy mission. Once whole-genome analyses frame the broader narrative, Y and mtDNA lineages can flesh out specific details like sexual demographics or tenuous connections between populations not discernible via other methods.

Y and mtDNA lineages are both technically uniparental markers because they are passed from one parent only, the Y from the father to son, and the mtDNA from the mother to child (although sons do not pass their mtDNA to their offspring so they’re dead ends). So the information they convey isn’t quite as remote as exhibits at the local historical society. Within genetic genealogy circles, a person’s direct paternal and maternal lineages have undeniable emotional valence that earn them a certain unquestioned primacy, even though those narrow lines of descent are not uniquely privileged in any scientific sense. The Y and mtDNA lineages exclusively trace back very specific and precise ancestors within a family tree. If I meet a Polish man who carries the R1a1a haplogroup, I know with certainty that we share a direct common forefather about 5,500 years ago who lived somewhere on the Pontic steppe of Ukraine. Some 220 generations of fathers and sons stretch back to a single human, the direct paternal ancestor of my sons, me and about a third of Slavic men.

Haplogroups are a way of “carving nature at its joints,” along familiar lines that strike humans as natural and accessible. Every single Y haplogroup traces direct paternal ancestry along a chain of men back to the origin of our species (and earlier if we had the data), while the mtDNA haplogroup is the genealogy of all of our mothers, back to the evocative “mitochondrial Eve.” These simple and direct genetic lines hew conveniently to the same assumptions as our cultural traditions of surnames, and they faithfully reflect our species’ fixation on patrilineal and matrilineal descent. Both of which tread that tiny track of a person’s descent solely along the direct genealogies of a single sex, just like the Y chromosome and mtDNA do respectively. And within the context of human demographic history, paternal and maternal dynamics do vary in interesting ways that can be uncovered by haplogroup distributions and the phylogenetic trees in which they’re embedded. It is amazing, if unsurprising, for example, to confirm that in racially mixed populations in Colombia almost all the mtDNA haplogroups are indeed indigenous to the Americas, while the Y chromosomes look like a subsampling of Iberian men. The mtDNA and Y studies add a quantitative dimension to the qualitative lore.

Today Y and mtDNA lineages play a supporting role to whole-genome analyses in the constellation of insights we can assemble about our evolutionary genetic past. Because we know so much more with 21st-century tools like whole-genome sequencing and fields paleogenetics, these two markers can now truly come into their own to explore very precise demographic phenomena, rather than being unrealistically tapped to illuminate the totality of the human demographic past.

A haplotype

So, what is a haplogroup? It’s really just a catchall for a set of related haplotypes that go back to a common ancestor within the genealogy. Okay, and so then what is a haplotype?

The human DNA sequence comes in two copies, a single genome of three billion bases duplicated into two strands, packaged and organized into chromosomes. That means every single one of our genes has a two-fold redundancy; with the key exceptions of the sex chromosomes in males and mitochondrial DNA in all of us. Every single position in the genome, when called upon for input, turns and confers with a partner before registering its vote or rendering its edict. Except, that is, for every lonely little position (of which there are more than 50 million) on each man’s runty little Y chromosome, as well as each position on the tiny but mighty engines that power every single one of our cells, our mitochondria (vastly shorter than the Y, with only 16,569 positions), these latter a bequest from each child’s direct line of female ancestors at their conception.

In addition to there being billions of positions in the genome that align themselves in a sequence, the genes within organisms are arrayed in a set order and bundled into specific chromosomes. They don’t just float free in the nucleus; they’re often packaged within a precise structure. The further the evolutionary distance separating two species, the more likely they are to differ in the order of their genes (and the total number of their chromosomes; humans have 46 chromosomes while our great-ape relatives all have 48). In contrast, within species, you generally have the same gene order.

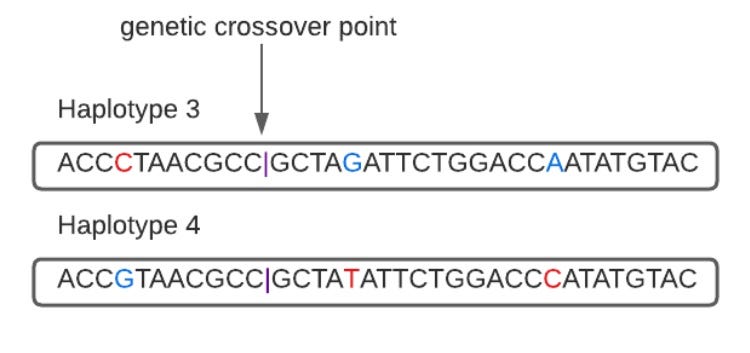

But in these ordered genes there is still variation. It is the variable positions, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), myriad A’s, C’s, G’s and T’s, when clustered together in a specific sequence, and correlated in their inheritance as a block, that characterizes a haplotype. A haplotype is defined by linked genetic variation on a DNA segment inherited as a unit from a parent. The figure below illustrates two short sequences that are almost identical but vary at three positions, 4, 16 and 27. Haplotype 1 reads C, T and C respectively at those positions, while haplotype 2 reads G, G and A. Since all genes except those on the male sex chromosome, come in two copies, you can see how an individual might in fact carry both haplotype 1 and haplotype 2.

In most of the human genome, these sequences of linked SNP variation become fragmented and decoupled from each other over generations due to genetic recombination, as segments of DNA break and cross over to match the alternative copy within your genome. Imagine, for example, if a single person of Chinese ancestry were to appear and marry a native of a small Swedish village; in that first generation of their offspring, the Chinese parent’s genetically distinct ancestry would be clustered together along long stretches of DNA (the chromosome pairs would all be exclusively Chinese or exclusively Swedish, one homolog from each parent). But in each subsequent generation that their descendants remain in Sweden mating with Swedes, the ancestral Chinese segments will be broken apart and recombined with DNA of European origin. After many centuries, the traces of the original long Chinese haplotypes of linked variation will only be detectable as much shorter segments.

We can illustrate the mechanism in a single generation with the above haplotypes if they swap sequences after breaking, in this case between the eleventh and twelfth letters.

The haplotypes are now CGA and GTC, rather than CTC and GGA.

When males and females form sperm and egg cells during meiosis, we expect about 20-40 crossover events to occur, swapping segments across the chromosome pairs inherited from the individual’s mother and father respectively (as well as the X chromosome for females). These breaks and swaps between the chromosome pairs can compound over the generations, decreasing the linkage of genetic variants across segments of the DNA, chopping up very long haplotypes. This perpetual dynamic that works against linked variation is why the presence of both very long and common haplotypes often merits closer inspection. For example, among both a majority of Europeans and a large minority of South Asians, one of the longest haplotypes is found spanning the lactase gene, in a segment over a million bases long (it would be 1.7% of the length of the Y chromosome).

Why is this haplotype both long and common? It owes its immense popularity to the little fact that it includes a SNP mutation within lactase that confers lactose tolerance, a trait that has been under very strong natural selection among milk-drinking pastoralists over the last 3,000 years. If a favored SNP increases in frequency fast enough due to strong positive selection, then coincidentally adjacent portions of the genome will “hitchhike” along, overwhelming the usual plodding, but inexorable, progress of recombination, leaving a very long haplotype at a high frequency in the population.

The detection of a long haplotype is a possible sign that Charles Darwin’s primary evolutionary force, natural selection, has been stomping through the human genome, leaving in its wake a vast desert barren of genetic variation. The haplotype around lactase is a copy from a single individual that likely lived around 5,000 years ago in central Eurasia, so in the majority of Northern European genomes, there is no difference at all between their two inherited chromosome copies.

But let’s rewind to where I said that in most of the genome haplotypes break apart. Our story today is not the vast bulk of the genome where all that conferring and recombining and crossing over confers. For haplotypes, our informants are the tiny fractions of the genome that take a road less traveled. And their solo journeys have made all the difference. The mitochondrial genome and most of the Y chromosome are by design unpartnered dancers, appearing intact in every act as evolution marches forward, never collaborating or conferring with anyone (there are some exceptions that are not relevant to this discussion). On the Y and mtDNA, mutations that arise together stay together like graffiti accumulating on a wall over time, because there is never any recombination to swap them onto another segment. The only way the mtDNA and Y sequences morph over time is when they accumulate new mutations. There is neither mixing nor matching of variants. Whereas for example your chromosome 1’s are likely to be a mishmash of your four grandparents because of recombination in your parents, the mtDNA is simply that of your mother, and her mother, and her mother before her. A male's Y chromosome is simply that of his father, his father before him, and so forth.

The evolutionary history of haplotypes in most of the genome would be hard to reconstruct because of the complicating variable of recombination scrambling the segments, producing a plethora of haplotype variation over the generations. Happily, for our purposes, this disqualifying complication does not apply to the Y chromosome and the mtDNA. They instead are just singular haplotypes, from beginning to end, accumulating variation through mutation in a clocklike manner over the generations. The simple evolutionary-genetic dynamics of the Y and mtDNA alone make demographic inference easy because you have only to work back up a family tree to the common ancestors.

A haplogroup

So, if a haplogroup is just a set of related haplotypes that share a common ancestor, does that mean that defined broadly enough we are all part of the general human haplogroup? Yes, because in the context of the two types of uniparental lineages, the Y and mtDNA phylogenies, they of course coalesce all the way back to the most recent common ancestors embodied by mythical individuals we call mitochondrial Eve and Y-chromosomal Adam. Despite these evocative names, to work with uniparental lineages is to be forever condemned to have to emphasize that these two individuals were not the only humans alive in their generation, and did not even necessarily contribute a disproportionate amount of their ancestry to humans alive today. It’s just that according to the mathematics of uniparental inheritance, eventually all competing unbroken lineages but one will die out, so that a single line descended from a common individual ancestor will encompass the whole population. It may be random, but it’s also inevitable.

The logic of this is not unique to DNA; it is reflected in our cultural genealogical traditions. Nearly 2,000 years ago, Emperor Augustus was concerned with the decline and extinction of Rome’s noble families. These were organized in gens, descended from common male ancestors whose status was inherited by the chain of legitimate patrilineal descendants. What Augustus did not understand is that the problem was not the morals of the nobility, but the custom of patrilineality in an officially monogamous culture, as many men in each generation would not happen to beget legitimate living sons to perpetuate their family line. Augustus craved the reliable fecundity (and blithe lack of concern about paternity?) of rabbits, in a world where the quest to achieve fatherhood looked more like a March Madness bracket, collapsing generation by generation. As a tragic example, Emperor Marcus Aurelius had at least seven legitimate sons, but only one, the insane Commodus, survived into adulthood (when his antics got him assassinated). In a patrilineal or matrilineal system, one needs an unbroken line of males or females, and the nature of probability means some lineages will go extinct every generation as the sequence of males or females is finally interrupted.

But what of those families that flourished and became prolific? In Rome, different branches of a particularly numerous gens became functionally distinct. During the late Republic, the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla had the senator Lucius Cornelius Cinna killed because the latter supported the enemies of the former. Though both were of the gens Cornelii, the Cinna and Sulla branches were by the first century BC considered separate families with no particularly strong connection. In the language of haplogroups, the Cornelii were the macro-haplogroup, while the Cinna and Sulla were descendant haplogroups. As some haplogroups go extinct, others diversify to fill the gap, so that eventually all haplogroups will be found to descend from a common ancestor, just like the Cornelli.

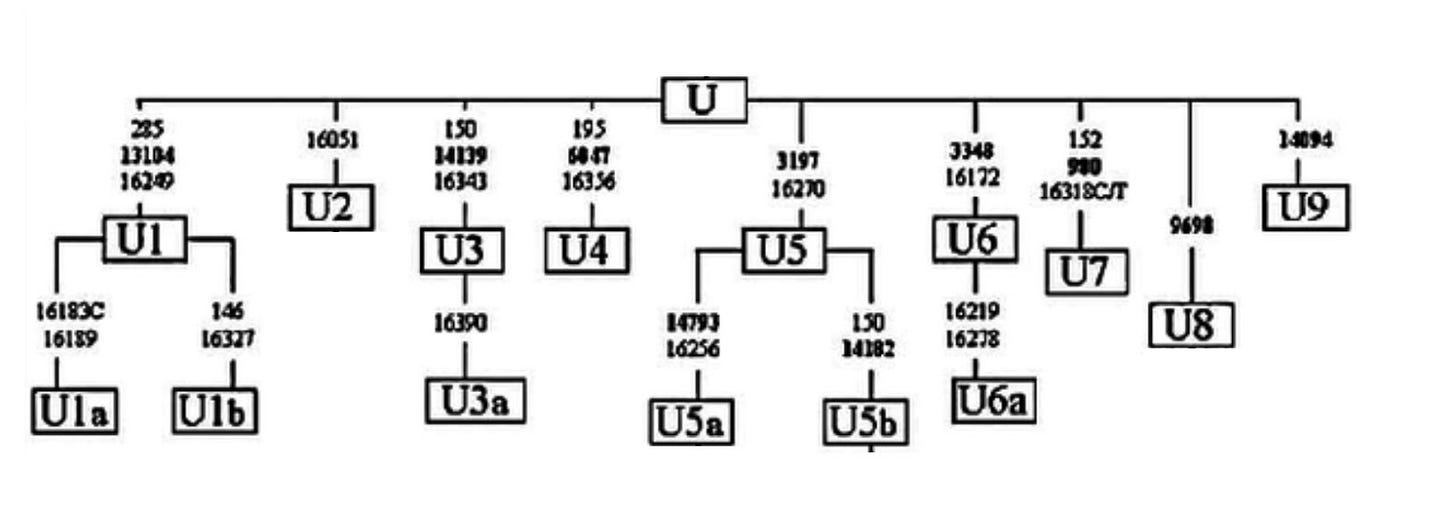

Because Y and mtDNA sequences build up mutations as they march forward through time, their phylogenies are defined by new mutations that accumulate within their family trees, demarcating a significant branchpoint. At some specific time in the distant past, all lineages shared the same common mutations in the last common ancestor, but over the generations, new variants came to define this or that branch. If one particular lineage was reproductively successful, it would come to beget many smaller branches descended from it. Above is a figure that defines the branches of the Y-chromosomal haplogroup R differentiated by the numerous mutations that accumulated over tens of thousands of years (the best estimate is that R1 and R2 separated 35,000 to 40,000 years ago). Though there are different nomenclatures for Y and mtDNA haplogroups, this common system is rather simple in how the names track with the mutations. First, two mutations, M479 and M173, define the split between R1 and R2. Then, within R1 you see the mutations that define R1b and R1a, and next within R1a you see the M17 mutation, which defines R1a1a (the process goes further within R1a in this tree, and some genealogical fanatics define unique mutations that trace close branches of the same family).

There are cases, like in mtDNA haplogroup U below, where mutations occurred so close in time we cannot define bifurcations, so many branches emerge from a single node.

Finally, just because mutations define a particular branch does not mean all of them to have the same importance to us. Within R1a1a, the Z282 and Z93 mutations retain outsized importance because they define lineages that encompass the vast majority of European and Asian males of this haplogroup and are associated with the massive demographic expansion of Indo-Europeans out of the Pontic steppe.

In the concluding post of this two-part series, we’ll begin to explore what haplogroups can really illuminate and why in the sweeping saga of the human race.

Best explanation of haplo since my Berkeley days in 1969 with Savage as lecturer.