The holidays are upon us. By way of thanking all of you for being so willing to support my fledgling substack project, this week I'm releasing a little set of year-end mini-posts. These are five quick daily reads about the state as I see it of five sectors I follow. Might have been perfect for raising the level of chitchat at a normal year's run of December parties. In 2020, I hope they'll edify if it's not your field and that you'll let me know what I'm missing if it's your bailiwick I'm reflecting on.

Thank you for reading, for subscribing, and for forwarding to friends who you think might enjoy. A quick administrative note: I'll be adjusting my Substack price levels upward in the new year so now is a great time to grab a paid subscription if you've been considering. Or to use Substack's gift option while the prices are lowest. Cheers!

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In the late 2000s Peter Thiel and Tyler Cowen made waves arguing that technological progress had declined since the middle of the 20th century. Having spent my adulthood in the period between 2000 and 2020, I was quite open to the idea. I watched the Jetsons. We don’t live in the world of the Jetsons.

But there is room for hope. We may not have flying cars, but we are now grasping the machinery of life itself and reshaping it. To behold today’s changes in biology is to witness a revolution.

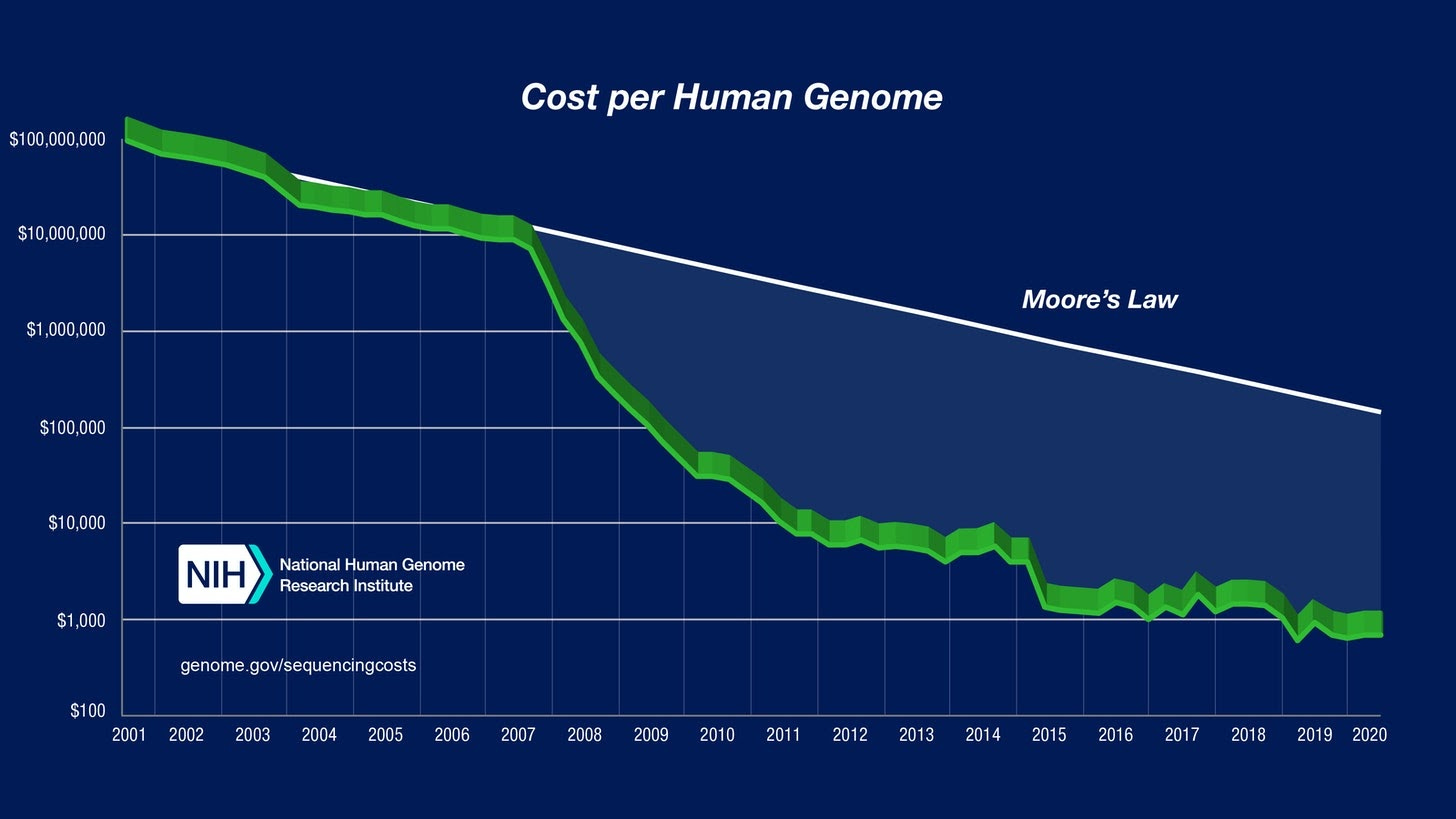

The last twenty years have seen a massive crash in the price of genomic sequencing:

While the first human genome cost $3 billion dollars, you can now get a good quality medical-grade genome for $1,000. I got my genome sequenced during a sale for $300 two years ago. Meanwhile, in 2014 I got my son sequenced while still in utero for free as part of a university project. In less than a generation, genomics has gone from blue-sky giga-science to cheap commodity consumer technology. About 10% of Americans have availed themselves of direct-to-consumer genomics, and it is so banal that South Park even did an episode on the theme.

CRISPR!

If genomics is the reading revolution, then genetic engineering is writing. Strangely, genetic engineering predates genomics by decades, in the form of recombinant DNA technology. This is a cumbersome method of modification whereby gene fragments from one organism are inserted into vectors such as bacterial plasmids or viruses, which can then transfer them into the organism of interest. Though this technology had early successes in the 1970’s, its application was constrained due to limitations in scope and scale. The clunky multistep process of cutting DNA and stitching them into intermediate vectors which must be grown in cultures, and then inserted into the target organism, required large investments and deep institutional support. This is a reason that genetic engineering with recombinant DNA was notable in the context of agribusiness. Massive corporate resources were necessary to implement and execute the technology as anything more than a curiosity.

If recombinant DNA technology allowed us to play God, it was a small primitive tribal god. As long as genetic engineering was restricted to expensive tinkering you’d be more likely to encounter it in science fiction than Scientific American.

CRISPR-Cas9 changed this in 2012. This form of genetic engineering became mainstream within science almost immediately and transformed laboratories overnight. It was a revelation in its power, flexibility, and ease of execution. Recombinant DNA technology arose in a pre-genomic era. CRISPR came to prominence during a period when genomics was already a banal part of a biologist’s toolkit. Not only was CRISPR technology much more effective as far as genetic engineering went, biologists now had “maps” that they could use as guides, rather than grasping blindly through vast, uncharted terrain. It is like the difference between Phoenicians sailing into vast oceans guided only by the positions of the stars, and the celestial mechanics deployed by NASA to explore the solar system with laser-like precision.

Innovation’s preconditions

The confluence of technologies is critical for takeoff in a particular sector. The ancient Greeks had primitive toy steam engines, but their mathematical and metallurgical science would not have enabled full-scale industrialization. It was not just a lack of vision or focus. The ancient world was not ready to harness steam as the motor for industrialization.

Similarly, mass-scale genetic engineering wouldn’t have been feasible even if CRISPR-Cas9 had been discovered in the 1980s. For example, the gene for Huntington’s Disease wasn’t identified until 1993. The major age of gene discovery actually post-dates the development of early genetic engineering. The PCR method which makes genetic testing so simple and ubiquitous wasn’t widely used until the 1990s. Also, advances in other fields like stem cells produce incredible synergies between the ability to edit genomes and their practical applications in medicine and health. CRISPR-Cas9 allows for the efficient and precise editing of genomes, but modern stem cell technology allows for the production of modified cells at a large scale that will not be rejected by the patient’s body.

The end of Mendelian disease

Genetically edited stem cells were critical in the breakthrough that may help cure many individuals suffering from sickle-cell disease. This illustrates the reality that genetic engineering is not magic. There are important practical questions of how you edit the cells, and how you can get the changes to suffuse tissue and effect a cure. But in many cases, those obstacles will be overcome. There are encouraging trials in dogs on muscular dystrophy, a disease caused by mutations in the largest gene in the genome. Trials are also beginning for cystic fibrosis. These are two childhood and young-adult diseases which inflict great suffering upon so many, but which may soon be wholly unfamiliar names to the young.

What these diseases have in common is that they are Mendelian conditions caused by impactful mutations in single genes. Often they are recessive or sex-linked. They are the bread and butter of medical genetics. But will they always be?

Because of the simple genetic characteristic of these diseases, the “target” for genetic engineering is narrow and precise. Fix the mutations and fix the diseases.

A combination of prenatal screening and gene editing in adults may mean that many Mendelian diseases are stamped out in the next twenty years.

The persistence of polygenic disease

Many conditions are not due to simple genetic causes but rather to a mutational burden across many genetic positions. There are hundreds of genes implicated in the risk for type 2 diabetes. And then CRISPR-Cas9 is a notably accurate and precise technology, but even it sometimes produces errors. “Off-target effects.” Attempting to fix polygenic conditions may introduce many new errors (perhaps, soberingly, even causing cancer).

Also, polygenic diseases often have environmental factors that impact risk, so a genetic fix may not “cure you.” It would just alter your risk profile.

The reality is that for most genetic traits, which are due to lots of genes, genetic engineering will be a matter of science fiction for at least another generation. It is worth noting, that unfortunately, it is unlikely that there will be a genetic cure for schizophrenia or autism, which are highly heritable mental illnesses caused by mutations across many loci.

The genetic engineering of “things”

The other major aspect of the “writing revolution” in genetics in the 2020’s besides better health through the beating back of Mendelian diseases is likely to be in the area of the modification of non-human organisms. In other words, basically everything besides us. GMO’s are still taboo in much of the developed world, but on a planet of eight billion humans subject to the exigencies of climate change, it seems likely that many nations will begin to invest in producing better crops and livestock to wring more out of scarce land. Mistakes in the context of medicine and health are deadly, but in plant and animal breeding dead-ends are common and not problematic. Due to simple Malthusian pressures, it is easy to imagine the proliferation of heat and cold resistant crops or super fecund livestock that are more efficient at converting feed to meat. “Meat things.” Traditional practices are limited by the methods of evolution, breeding within a species or amongst closely related species. Genetic engineering opens up the possibility of broad synergies across the tree of life. Keeping things “natural” and “organic” may become a developed-world luxury. Intelligent design in evolution may not be our past, but it could be our future!

An unnatural world

The next decade will not see an end to hunger or illness. But, there may well be less disease. There will be more choices for producers in crops and livestock. The phrase “better living through chemistry” dates to the 1930’s. The 2020’s may usher in “better living through genetics.” Though I suspect that this revolution won’t be advertised...

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Thank you again for reading, for subscribing and for forwarding to friends who you think might enjoy. A quick administrative note: I'll be adjusting my Substack price levels upward in the new year so now is a great time to grab a paid subscription if you've been considering. Or to use Substack's gift option while the prices are lowest. Cheers!

a friend pointed out that just because locus are of small effect, one might still be able to target that locus with a drug and case a huge phenotypic change. so the polygenic part of the newsletter may be on the pessimistic side.

here is the explanation https://www.gnxp.com/blog/2010/02/small-genetic-effects-do-not-preclude.php

There is an ongoing clinical trial of a treatment for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy by Systemic Gene Delivery https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03375164

The PI for that trial is the man who was PI for the development of Zolgensma (onasemnogene abeparvovec-xioi) which targets the genetic root cause of spinal muscular atrophy in infants by replacing the function of the missing or nonworking SMN1 gene with a new, working copy of a human SMN gene. https://www.zolgensma.com/how-zolgensma-works.

We are living in the 21st Century.

We should also give some credit to genetic technology for the creation of the 2 new vaccines against Coronavirus. Less than a year after the virus was identified and sequenced. It is an awesome accomplishment. Further, the underlying mRNA technology could be extended to other diseases, including cancers.