So you want to test your DNA

A genomicist tells you what tests are worth it for you, and why

NOTE: Neubla genomics seems to be having problems with fullfillment right now

It will surprise no one who reads me or has met me in real life that I’m not very acquisitive. I don’t have prize possessions. Never have. I am an avid consumer of exactly three things: spice, ideas and data. You’re on your own for peppers (or hot sauce, although in another life I used to write quick and dirty hot-sauce reviews) but as always, I have strong opinions about what and who is worth reading. I’ll share a Cyber Monday roundup of those in a separate post of reading recommendations (along with my only annual mega discount on Substack subscriptions). And aside from investing in your brain, there is exactly one thing I believe everyone, from an infant to a nonagenarian should own, possibly in multiple formats, for their (and their descendants’) own good: their genotype or especially their Whole Genome Sequence (WGS).

In this post, I will take you through the trade-offs as you decide what product is right for you or your loved one, as well as a bit of the history and the science behind these products. There has never been a better time to first get your WGS or genotype and I frankly envy anyone who is just weighing their first little investment. It’s amazing how differently I would advise you now than just four or five years ago! I have been buying genotyping services and then WGS kits for myself, my extended family and friends since 2009. I have also worked for nearly a decade behind the scenes, customizing the genotyping chips that power the kits and drafting the ancestry explanations consumers receive for many of these products. When Henry Louis Gates’ team prepares an episode of Finding Your Roots, they run the raw results by me to be sure we concur on the conclusions about the guest’s ancestry. I live and breathe consumer genetics and here I share my recommendations with you based both on my first-hand experience buying them and my work as a genomicist seeing how these products come to be.

So you want to test your DNA

There is no competition for my first pick, the gold standard: a Whole Genome Sequence (WGS). In 2000, it took nine months and cost taxpayers $100 million to assemble the first human genome. It still wasn’t in my price range, but I vividly remember my excitement in 2010 when the first consumer options in this field emerged with a price tag of around $10,000. I leapt at the chance to own my WGS (and share it for research) in 2018 for $299. Depending on whether you catch a flash sale, for as little as $199 and a wait time of six weeks or so, today anyone can have their own Whole Genome Sequence of exactly the same fidelity as that game-changing multi-million dollar version two decades ago.

Your choices for this product are Dante and Nebula. Dante offers one product and Nebula three. Dante’s one offering and Nebula’s best bet are both the 30x WGS. 30x is a measure of coverage, or how many times short, several-hundred-base-long sequences align to the same part of the genome. Every pass further overwhelms the occasional misread, improving accuracy to the industry standard for precision and accuracy. Nebula will also sell you a 100x kit, which to me, is just a tax on the uninformed. A typical Illumina machine might have a 0.1% error rate per base position. 30x samples the position about 30 times, allowing you to be sure that a variant is a true call and not a false positive error. By 100x, you are well past diminishing returns and just paying for vanity. I don’t see the added value. 30x is good enough for academic labs, mind-bendingly good, honestly. This is your best bet. Nebula will also sell you a bargain WGS product with 0.4x coverage. Again, I don’t see the value. Either get the 30x or just get a genotype (I’ll get to these next) with a slicker interface and a richer community experience.

So, what is the value of a WGS? Unlike genotyping which is subject to reconfigured chip design over time and continues to be improved upon, with the subset of alleles and genes assayed on its chip tweaked and updated, the WGS is already… everything. To put it simply, this is an appreciating asset, the opposite of a car. No judgment calls from the scientists customizing a chip, just everything from the most trivial to the most consequential, at your fingertips forevermore. You’re getting a read on every single position in the human genome we know how to read (which for all intents and purposes, is everything). It can be downloaded and it will last forever. The data underlying any medical genetic question you might subsequently need to answer in the coming decades will already have been collected.

This might seem counterintuitive, and my family is undeniably unusual, but I actually find this product as appealing a gift for those who don’t have decades of medical or ancestry questions ahead of them as I do a must-have investment on your minor kids’ behalf. Or frankly, if the octogenarian or nonagenarian is you, it’s a thoughtful bequest for your genomically engaged progeny. We find it comforting to know that when my kids’ nearly 90-year-old grandfather is gone someday, no longer gamely turning up his hearing aids to try to follow the day’s mumblecore dialog, we already have his WGS banked forever, for anything we wonder about as subsequent genetic discoveries and interesting findings emerge. This is an unusually hale human whose prodigious memory shows no signs of diminishment in his late 80’s, despite having spent his working years skimping on sleep and being much more intimate with pie crust than cruciferous vegetables. What if any of those lucky quirks will someday prove to have a genetic basis? And if any do, which might my children have inherited? In a similar vein, if my maternal grandfather, a pioneering doctor who lived to 100 were alive today, I would leap at the chance to bank his WGS for my future curiosity, too.

Who shouldn’t get a WGS? I think this has value to everyone alive. But if your budget is very limited and your purposes are purely to find relatives or join an active community of genealogy enthusiasts, you will get more out of a genotype product (which I’ll cover next) than a WGS.

One group who I know is sometimes reluctant about all genetic testing products is people with a known brutal condition in their pedigree that will be a matter of an autosomal dominant coin-toss. Many simply do not want to live with that knowledge. I haven’t been in your shoes; in my family, the harshest stuff is best managed with drugs from childhood, so we want to know as early as possible. What I will say is that your entirely valid personal choice doesn’t diminish the value of the rest of the WGS. Don’t want to check the Huntington’s Disease read in your results? By all means, don’t. But don’t let that keep you from owning your WGS for all the myriad other reasons it could be useful and interesting to have. And know that you’re in good company. I’d estimate one in five friends who get a WGS tell me there are results they choose not to view.

Finally, which is better, Nebula or Dante? The 30x WGS will give you exactly the same genetic data at exactly the same fidelity from either. Nebula sells you a subscription for their interface, too, which I don’t love. But depending on your comfort DIY-ing it, you can plan to simply download the huge file once it arrives, which in the case of Nebula would allow you to discontinue your subscription within the first months. To do this, you select the quarterly “Nebula Explore Reporting Membership” option at check out and can plan to cancel after downloading your raw data. They will only bill you once sequencing is complete, adding $24.99 to your total cost. That being said, if DIY-ing it is not your preference, Nebula has clearly invested more in the user experience and interface, so the lifetime membership upsell might feel worth it whereas Dante still feels very bare bones. Both options will coddle you a lot less in their current iterations than the slicker (older and more developed) genotyping companies’ interfaces, but if you don’t need concierge service, you will own and be able to explore your entire genome from day one. If this isn’t living in a time of miracles for you, I can’t imagine what would be.

Genotyping: no one-size-fits-all

OK, but we are only four, or five years into the super-affordable WGS era. What most people know is direct-to-consumer genotyping: 23andMe, Ancestry, Family Tree DNA, etc. And as strongly as I’d urge everyone to consider banking a WGS, genotypes are still a great choice for a number of uses. These are the products about which people ask my professional opinion most. I am asked versions of all the following on a daily basis. What is the best ancestry testing platform? What platform gives you the most accuracy? What test can I trust to understand my ethnic origins and ancestry proportions? And I am admittedly a uniquely good person to ask, not only having bought dozens of the tests but having been involved in developing some of the methods that generate percentages of ethnicity, nationality and ancestry for a decade now. I’ve been there for the discussions between scientists, product managers, designers and marketers before the tests roll out to the public. I’ve written the ancestry stories you receive from some of the kits and I’ve liaised with the deeply informed community of genetic genealogists and hobbyists who are these services’ superusers and evangelists. But unlike with a WGS, where I tell everyone: just get one, any one, it will only increase in value, etc., the answers to these common genotyping questions vary based on who’s asking and what they want to get out of the test.

But what if they’re wrong?

First off, so are these tests accurate? How accurate are they really? Those are probably the very most common questions people reach out to ask me. I think there are two layers here. All these tests are today utterly, brutally accurate. Especially if you speak SNP, which most of us don’t. The chips call the single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), the bases that vary between one person’s genome and the next’s, incredibly accurately. More precisely, under validation, in over 99.9% of the cases, the genotype call is proven correct. A 30x WGS is still more accurate, but a consumer genotype is already incredibly reliable. But I realize that’s not what my non-geneticist friends are asking me. What people want to know is mostly how meaningful their ancestry breakdown really is. And that is where we depend on a human interface between the absolute statistical precision of the SNP calls and our nuanced, flesh and blood world. This layer is where art makes meaning out of science. And it is excellent overall and getting better with every passing year. But it still has shortcomings and specific lacunae. Let’s get into these.

The ancestry percentages a consumer receives are the outcome of a cascade of decisions that begin after the raw genotype comes back from the chip. If the result at a position is reported as AG, meaning you carry an A and a G on your two copies, you can trust that call with 99.9% confidence. Comparing my 23andMe, Ancestry, Family Tree DNA and National Geographic genotyping results to Dante’s 30x whole-genome sequencing service, I calculated 99.9% of the hundreds of thousands of markers were indeed accurate calls. They’re not making the results up; the chips work as advertised.

Today the genotyping services return reams of markers, with the current generation of chips reporting 600,000 to 800,000 SNPs per person at that 99.9% accuracy level. But on select markers, like those on the BRCA gene that can increase breast, prostate, ovarian and pancreatic cancer risk, even a 1-in-1000 error rate is too high. And given this, the genotyping services selectively increase the accuracy and precision of these crucial sites through various technical means so that the calls at these disease-relevant SNPs are more like 99.99% accurate (When customizing the chip, they designate more probes to sample those markers that code for the most functionally sensitive phenotypes, to assure watertight calls; for example, ten probes might be assigned to a single disease SNP, whereas other less dicey positions are pinged more like three times to make a final call).

Estimating ethnicity

And of course, when people ask me if DNA tests are accurate, I know they’re not asking me if the millions of letters of raw genetic code they downloaded are accurate from SNP to SNP. They just want to know if they’re actually 1% Nigerian and 99% Northern European like 23andMe said. In this specific case, yes, I’m sure this is perfectly true and informative. But if you are Japanese and the service reports that you are 0.1% Ashkenazi Jewish, I wouldn’t believe that (these are both real examples from friends).

How do I make these judgments? Well, in the first case, I happen to have read a 23andMe white paper that noted that their simulations indicate that their method returns a 50% false positive rate below 0.1% Sub-Saharan African ancestry against a European genetic background. This means that by the time you are up to 1%, you’re ten times over that still-noisy threshold, so they’re almost certainly detecting real admixture. On the other hand, when it comes to the Japanese person with a 0.1% Ashkenazi background, I know that companies are banking on the finding that many customers really like 0.1% granularity (this is from market research surveys), but scientifically, this level of faux exactitude often results in false positives.

There are scientific and historical reasons for the different thresholds in these two specific comparisons. The evolutionary split (as in, the last common ancestor) between Ashkenazi Jews and Japanese dates to about 50,000 years ago, while between Sub-Saharan Africans and all non-African humans, the divergence point is 100,000 years ago, long before the “out of Africa” migration. That makes it easier to detect Sub-Saharan African ancestry against non-African genetic background than it is to sort different stripes of non-African ancestry. The closer the genetic relationship of two populations from which you are putatively mixed, the more you have to increase the threshold to eliminate any risk of the minority component being an uninformative false positive (or just a matter of shared ancestry between two closely related but truly distinct groups, like Swedes and Finns).

My point in walking you through this minutiae is to underline that there are masses of decision points to navigate as you translate hundreds of thousands of A’s, C’s, G’s and T’s into a crisply partitioned ethnicity pie chart. The SNP data might be spit out in stark black and white, but humans have to choose the parameters in the model to deliver the consumer meaning. How many populations? What do you label them? How sensitive (and thus prone to miscalls) do you tune your needle? How do you define the scope of a given reference population and where, geographically within that nation, do you sample it from?

What you’re up against: tradeoffs when designing a test to estimate ancestry

First, How many markers do you want to use? Today all the services are far beyond any definition of enough, usually more than 200,000 markers, so this no longer distinguishes one service from another. In the past, they didn’t have as many markers on the genotyping chips or such massive computing resources, which all used to yield some pretty noisy results in the early 2010’s from the earlier versions of the current offerings and as well as from now-defunct services. Noisy results that suggest you are a trace amount Japanese when you know you are Norwegian are intriguing, but they’re not true (for what it’s worth, misassigned “Japanese” ancestry in Norwegians would most likely be a matter of detecting Sami admixture).

Next, how many “reference” individuals did the service utilize to train and test their model? To determine if you are English, a service could compare your data to 1,000 validated English samples or to just 25. The former is obviously more powerful and informative than the latter, but it is far more computationally intensive and thus expensive. Again though, these long-time concerns are slowly sunsetting as computation gets ever cheaper. Every year, you can count more on the services to harness the power of huge reference panels (if you were an earlier adopter and haven’t circled back to your results, this may well have been your experience in the early 2010’s, though).

Third, do they have a diverse reference population set? English samples are obviously easy to obtain, but what about other reference populations? There were cases ten years ago when many populations were not yet in public databases so you couldn’t return good results on them. There were no East African reference populations yet, so Somalis would come back best modeled as part European and part African. And early on, without South Asian reference populations, every Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi came back as a mix of European and East Asian. Today, we’re far beyond those early days. But still, a native Hawaiian may come back as 4% Papuan, which is the closest to the 25% Melanesian ancestry component found in modern Polynesians. So in that case, I would caution anyone with this ancestry to take the specific percentages with more of a grain of salt than ancestry like Japanese or Nigerian, both of which are well-represented in databases.

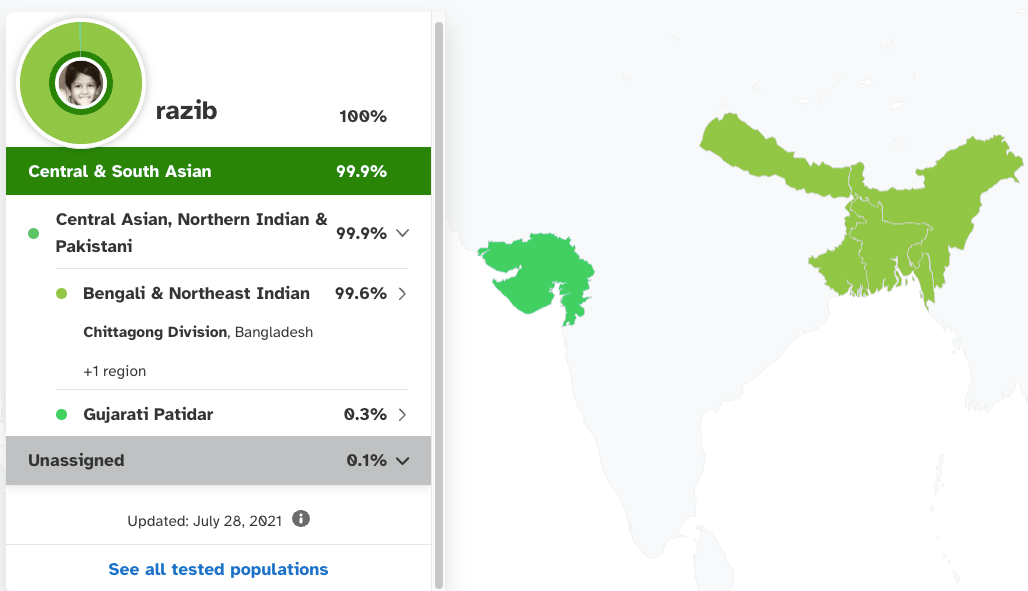

For the end product, you’re also at the mercy of what finite array of populations are available to assemble your ancestry. For example, 23andMe tells me today that I am 99% Bengali, with ancestry from the Chittagong division of Bangladesh. This is all true. But with the state of the art in 2010, 23andMe told me that I was 50% European and 50% Asian in ancestry. This might seem crazy, but their overall model at that point had just three major reference populations: Asian (Chinese and Japanese), European (whites from Utah) and African (Nigerian Yoruba), and so despite me roughly genetically resembling a billion+ other humans, their best model based on what was then well sampled was midway between European and East Asian. As it happens, 85% of my ancestry is conventional South Asian, with 60% of that subset of my heritage closer to Europeans and 40% closer to East Asians (the product of a prehistoric admixture in the subcontinent between steppe pastoralists moving southeast out of Iran and Afghanistan and indigenous foragers distantly related to Southeast Asians and farmers). Another 15% of my ancestry is very similar to Southeast Asians, like Burmese (the product of a generalized admixture in Bengalis that distinguishes us from other South Asians and dates back to 500 AD). Running this math, (85% x 40%) + 15%gives 49% Asian, just like the 2010 algorithm stated.

Today, 23andMe can detect that I’m nearly 100% Bengali because my particular genetic mix is very common in Bengalis… so the machine learning algorithm has long since been trained to detect generic Bengalitude (which I embody… sort of). But in the process of making that designation along national lines, it masks what is genetically distinctive about Bengalis compared to other Indian subcontinental people: that we’re non-trivially East Asian. Also, it elides the significant variation within Bengalis, just calling all of us who fall within the typical range: garden variety Bengali. I can look at my data myself and see that I’m more East Asian than most Bengalis, more than any of my near relatives. Two Bengalis might both be correctly recognized to be 99% Bengali, but under that umbrella, one could actually be 10% East Asian and another 17% East Asian (both are actual common values I’ve frequently observed within the Bengali population).

Different kits for different reasons

So back to the overarching question, what is the best genotyping kit for you? It really depends on what you specifically want to know. Due to corporate decisions that date back to a CEO-driven preference earlier this decade, Ancestry has long since discontinued returning markers on the Y (paternal) or mtDNA (maternal) regions of the genome to the consumer, so if you want to know your uniparental lineages, you should go with 23andMe or Family Tree DNA. Family Tree DNA, also for historical reasons of company culture (they have always really cultivated their genealogist super-users) offers many deluxe products related to fine-grained Y and mtDNA sequencing, so if you are interested in drilling down on uniparental paternal or maternal ancestry, they are your best bet.

Among the places where 23andMe and Ancestry shine is that they have the largest databases. This allows them to beef up their reference populations just from within their own customer database, scanning the results their chips generate for individuals that complement the academic samples all companies work from.

Here is a neat illustration of how far we have come from the early days I recalled above when a Bengali (member of the third largest ethnic group in the world, after Han Chinese and Arabs) could receive results suggesting hybrid Asian/European ancestry… to today when you have to be from a much smaller subgroup to routinely get a close-but-no-cigar assignment. A few months ago Dasha Nekrasova, co-host of the Red Scare podcast, got results from Ancestry saying she was a mix of Lithuanian and Ukrainian. She knew she was ethnically Belorussian; her parents are immigrants from Belarus. Why did it fail to recognize her as Belorussian? Her co-host, whom I know, had Dasha send me her DNA to double-check. I have Belorussian samples within my own database, and Dasha fell right in the middle of them. When I looked at Ancestry’s reference populations, they didn’t seem to include Belorussians, so the algorithm made her a combination of the two closest ethnicities to be found in their database.

This is exactly a latter-day, fine-grained version of my Bengali ancestry being called as half Asian, half European in 2010. No algorithm will ever account for the most obscure sub-group of a sub-group of a sub-group until that algorithm has been explicitly been trained on samples of it. But with every passing year and every additional population fed into reference databases, less of humanity can be regarded as obscure. No surprise that the human population numbering nearly 300 million was lower hanging fruit than the one of nearly 10 million. In any case, this means that until every human subgroup has been added to reference panels if any of your ancestry might be at all unusual, which kit you should prefer depends on your expected ethnicity and the ethnicities in the services’ reference populations. You can check for yourself and make the best guess about what service would answer your particular questions. If you’re having a hard time deciding, pop your expected ethnicity in the comments to this post and I’ll give you my two cents. And actually, you don’t even need to stop there. Since these services provide raw data, you can upload that to third-party services like Genome Link or My True Ancestry. These nimbler, smaller, boutique services tend to release features on a more frequent cadence and explore novel aspects of ancestry like your Viking heritage.

There are of course other considerations. Right now, 23andMe seems to have the richest offering of functional results among the major kit companies, so if knowing all sorts of traits (and some disease risks) might be rewarding to you, 23andMe is the best service. On the other hand, Ancestry has the largest customer database, so if you are adopted and want to find relatives, Ancestry provides the highest probability (best of all, if you can buy two kits, would be to combine the numbers between both Ancestry and 23andMe). And note the variation in database sizes: 21 million for Ancestry, 13 million for 23andMe and a bit over 1 million for Family Tree DNA. If you’re not looking for relatives, go with the features, where 23andMe is the best. If you enjoy exploring genealogical connections, Ancestry is the best. Though Family Tree DNA has the smallest database, it also has long had the most active genealogical community. If you want to get involved in an active community of genetic genealogists that’s been around for a couple of decades, then Family Tree DNA is a great option.

The average consumer now has access to DNA technology that the best labs in the world could only have dreamed of in 2010. Ours is an “age of miracles” where our genomics problem isn’t prohibitive cost or lack of computational power but the dilemma of what to do with such godlike gifts.

What to buy, in a nutshell

Money is no object: invest in a WGS from Dante (cheaper if you are happy to dig around in your data yourself using Promethease etc.) or Nebula (with a slicker interface by subscription if you want more structure and guidance) for everyone you love, young to old. Consider adding a basic genotyping kit (like 23andMe, Family Tree DNA or Ancestry) for recreational purposes and the fun of finding out percent relatedness to relatives both close and distant.

You seek your roots: genotyping is game-changing for people on either side of a closed adoption who long to connect. You up your chances of a hit with the size of the database you’re searching. So if you can afford both Ancestry and 23andMe kits, you’ll have over 30 million people to search among (obviously some subset will have done both tests).

You have health questions: WGS: Dante or Nebula, 100%. For $12 Promethease is aesthetically very bare bones, but will help you parse your WGS findings from either platform, based on all the latest health variants in SNPedia, so you don’t have to look up genetic positions manually. If I had health mysteries and suspected a genetic component, I would want my WGS to complement whatever targeted tests my doctor was ordering. Why not the Health & Ancestry product 23andMe offers? The price is only marginally higher than their ancestry-only offering, so why not, but be forewarned that FDA strictures have kept 23andMe health products extremely narrow and constrained. In contrast, Promethease is run by someone based in South Korea so the FDA is not a factor in what they can tell you.

You love genealogy: any genotyping service. Family Tree DNA and Ancestry have the most active communities. WGS services don’t have enough users to compete here.

You’re interested in your uniparental lineages (MtDNA or Y chromosome): 23andMe, Family Tree DNA, or other more boutique genotyping services, just not Ancestry.

Your ancestry is probably from an obscure group: check the coverage of your expected group in the reference panels of 23andMe and Ancestry and if you’re still undecided, pop your expected ancestry in the comments here and I’ll weigh in.

Wonderful counterpoint to the literary & symbolic aspects of genealogy e.g. here:

https://www.plough.com/en/topics/justice/culture-of-life/yearning-for-roots

https://www.plough.com/en/topics/life/parenting/the-name-of-my-forty-sixth-great-grandfather

Don't all of these services keep copies of your genetic data? I'm not comfortable with that.