RKUL: a little light reading, September 2021

a sampler of recent paid posts (with follow-up notes)

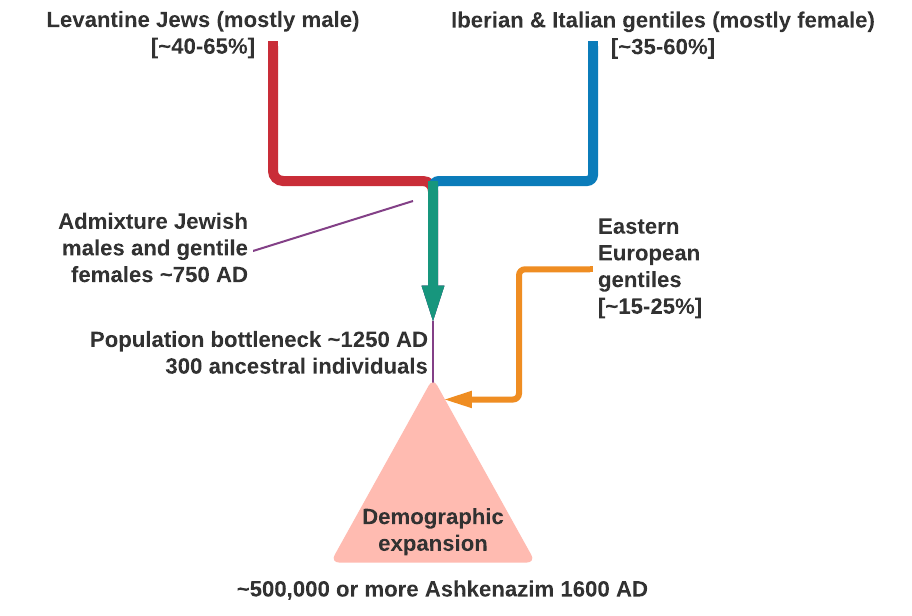

Ashkenazi Jewish genetics: a match made in the Mediterranean

The history and culture of European Jews have been fascinating us for centuries. Today genetics provides a new scaffold, allowing us to really get to the heart of the questions which have perplexed us for so long:

To understand when and where the Ashkenazim come from, it is important to understand what they were before they became the distinctive people we know from history and fiction. The ancient King David was a simple shepherd, while the Babylonian Talmud outlines how farmers must maintain adherence to the laws of the Torah despite the agricultural season’s cycles. 2,000 years ago, the Jews were both pedestrian and unique. Pedestrian in that they were a nation of farmers and shepherds, as extensively documented in the Bible. Yes, large communities of urban Jews flourished in Alexandria, Rome and other large cities, but on balance, the Jews were not particularly urban. Like the Jews, Greeks outside of their homeland tended to be urban as well, but the average Greek was still a farmer or a shepherd, as were the vast majority of humans in the ancient world (not to mention, incidentally in the world as a whole until the 20th century). The ancient Jews were tillers of the soil and drivers of flocks, like all their contemporaries.

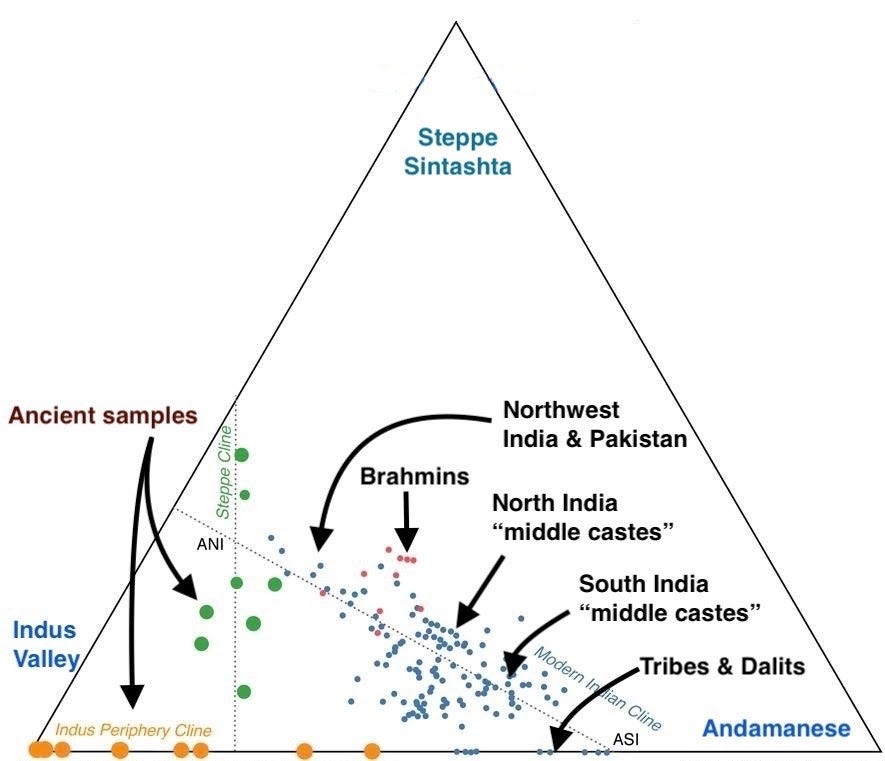

The character of caste: sorry white people, you didn't invent this one

There are some deep social and cultural facts that only genetics can truly resolve. The question of the origin and pervasiveness of caste is one of those. For the past few decades, a debate has been roiling about whether the complexity and fixity of caste is an artifact of British colonialism or an ancient aspect of Indian society:

The word “caste” itself may be of Latin origin, but Muslims and Greeks plainly saw the phenomenon of communities that married only among themselves (endogamously) and tended to specialize exclusively in particular occupations. Both al-Biruni and Megasthenes, 1,300 years apart, also detailed that according to ritual status, a group we would today recognize as Brahmins were at the top of the social hierarchy. This underscores that caste had been part of the Indian cultural landscape for thousands of years before the Portuguese bestowed the term “caste” upon the continent just five hundred years ago. How then could you see an article published in a respectable Indian newspaper with the headline “Did the British invent caste in India? Yes, at least how we see it”? The author of the piece argues that “there was no regularity or uniform pattern in the various stratification systems that existed over a large subcontinent demarcated by a medley of jatis…” After conceding that mainstream scholars like Sumit Guha, author of Beyond Caste: Identity and Power in South Asia, agree that some caste did exist prior to the British, the piece still persists in objecting to the widespread consensus, insisting that “other scholars, however, have serious doubts.” These dissenting thinkers assert that at that time, “caste could be changed as easily as moving from one village to another. And such instances...happened frequently.”

I should probably note that my discussion of the above Substack piece resulted in me getting mass reported on Clubhouse for “hate speech” and instantaneously disappeared from the app in the middle of hosting the conversation. Those supposedly offended were a group in the Democracy First club (left-leaning Indian-Americans who are opposed to Hindu nationalism and the Modi government), where some individuals showed up in my room and repeatedly mooted awkwardly worded ideas about intelligence and heritability, presumably meant to put the room in a negative light. My sources say one of them was recording the conversation in order to “report” me, while the other acted as the agent provocateur. After my suspension, friends observed them gloating in their own rooms, explicitly claiming responsibility. Luckily for me, I know people and was reinstated overnight. I obviously won’t stop talking about inconvenient truths and data, but I do wonder how many people this petty little gang of commissars have silenced with their coordinated method and the moderators’ obliviousness to anything that doesn’t neatly fit a social-justice rubric.

Podcasts

On the Unsupervised Learning podcast, my guests and I have dabbled in a broad variety of topics over the last few months:

And here are the currently ungated podcasts all in one place.

Most readers know who Steve Pinker is. A psycholinguist who is also one of America’s most prominent public intellectuals, Pinker has a new book out, Rationality: What It Is, Why It Seems Scarce, Why It Matters. His book subjects have traditionally swerved between those that focus on his domain-expertise, like Words and Rules, and works that cast a broader net over social, political and culture concerns, like The Blank Slate. Rationality is a bit of a hybrid, as I note in my review in UnHerd. In addition to his newest book, Pinker and I also discuss his take on the current temperature of the culture, and the consequences of the great “awokening” for the American intellectual scene. He’s still optimistic.

My conversation with fellow Substack writer Freddie deBoer mostly covers his book, The Cult of Smart, and Kathryn Paige Harden’s The Genetic Lottery. Since deBoer is a self-described radical socialist, I wanted to delve into how he could arrive at very deterministic views about educational outcomes. To be frank, I myself found deBoer a bit too fatalistic and hereditarian in some of the conversation, a position that’s rare for me, let alone with an egalitarian anti-capitalist.

Mahan Ghaffari and Emily Deans both spoke on the interminable COVID-19 pandemic, which seems set to drag along well into the fall of 2021. Ghaffari is an evolutionary geneticist who focuses on viruses, and we discuss technical details of how we can expect SARS-CoV-2 to mutate and change over time. Deans, in contrast, is a psychiatrist who has been following the pandemic since the beginning, and this conversation is a follow-up from an earlier one we had in the spring of 2020.

Finally, I explored the life and times of Antonio García Martínez, author of Chaos Monkeys. We discussed technology (and a bit about his “cancellation” by Apple), his identity as a Jewish convert, self-driving cars, and whether America’s decline is inevitable.

Reader comment

In Ashkenazi Jewish genetics: a match made in the Mediterranean a reader talks about his family background:

Thanks so much for this write-up. This is a part of my history that I knew nothing about until I was 42. I discovered it initially through genetics. My maternal grandmother had a surname of Kardos which is Hungarian for sword. She said she was descended from Hungarian nobility. I fantasized I was the descendant of Attila the Hun! My father's family came as refugees from Europe after WWII and his ancestry was a mystery also. So I fanaticized I was also descended from Central Asian descendants from Genghiz Khan. My father's side turned out to be Russian peasants like they said - Y-DNA E-V13 - with very distant links to all over European Russia and Eastern Europe.

Thanks to the Genographic Project, FamilyTreeDNA… I found my maternal grandmother had the mtDNA haplogroup K1b1a1b which is the most common Ashkenazi mtDNA haplogroup. Later we got records from Hungary that my maternal grandmother was directly descended from Cohens and Levites. It shows up dramatically in the autosomal matching in 23andMe and FamilyTreeDNA. Her parents were buried in the largest Jewish cemetery in Budapest. Her parents changed the surname from Kohn to Kardos in 1891 as part of assimilation. My grandmother and her sisters barely escaped Hungary. She left in 1933 because her husband was an early aerospace engineer who emigrated to the US in the late 1920s. One of her sisters was a senior student of Bela Bartok and escaped with the help of academic supporters in 1938. Another sister hid out in Budapest during the war. Most of her relatives ended up in Auschwitz. No wonder they would make up a fake story to prevent her children from the prevalent antisemitism.

Perhaps not that light…

When I posted 15 books that you will leave you changed last winter I left off Warren Treadgold’s A History of the Byzantine State and Society because it’s more than 1,000 pages, and I know many feel Byzantium is kind of an obscure civilization. But I regret not including it my the list because comprehensive doorstop though it may be, Treadgold’s is a very important book since Byzantium was at the center of world history for nearly 1,000 years. This book begins in the mid-third century and continues up to the 15th century. Treadgold tackles military, social and religious history in one fell swoop. You see the fall of the Roman Empire through the eyes of the Empire that didn’t fall.

You won’t need to read another book on Byzantium if you read this one. But I’m betting A History of the Byzantine State and Society will only whet your appetite...

Over to you

As always, I welcome paid-subscriber comments and your reading recommendations and suggestions. They never disappoint.

These people were obviously never present for an Uncle Razib lecture where you promise to make them famous. Promises made...promises kept.

Some other good byzantine history reading:

Michael Angold - The Byzantine Empire 1025-1204: A Political History. This takes you through an incredible sequence of events. The Romans are on top of the world in 1025, and in 50 years they have completely blown it and are losing their Anatolian heartland, which they had always been able to defend against the Arabs. Then they get it back together for about 100 years with the Komnenos dynasty and then fall apart again. The Larger lesson being that political systems and state structures can be quite fragile and respond to stress in self-destructive ways.

Mark Whittow - The Making of Byzantium, 600-1025. Takes you from the 7th century collapse through the long recovery and closes at the peak with strong focus on the limitations imposed by geography. Very interesting take on Basil II, whom he sees as a "traditionalist/reactionary" repudiating the 10th century conquest era with its focus on multi-ethnic alliances with Armenians and other eastern non-orthodox christians in favor of a return to Constantinople-centered orthodoxy. Implicit is the thought that the decline began with Basil, not after him.

Any books by Anthony Kaldellis. Kaldellis likes to stir things up and some of his arguments seem a bit out there as in Byzantine Republic, but in Romanland he is pretty hard to argue with on the fundamental Roman identity of the empire, and the bad faith agenda of the western world in trying to obscure that identity. Kaldellis has an interesting podcast as well.

Peter Sarris in Empires of Faith is looking at the entire late antique / early medieval world, not just Byzantium, but very interesting throughout, and interesting views on the 7th century collapse and early attempts at recovery.