RKUL: a little light reading, October (& early November) 2021

a sampler of recent paid posts (with follow-up notes)

Thanks for subscribing to Razib Khan’s Unsupervised Learning. October and early November brought paid subscribers two major pieces. Here are a couple of excerpts for free subscribers. Paid subscribers will find follow-up notes throughout.

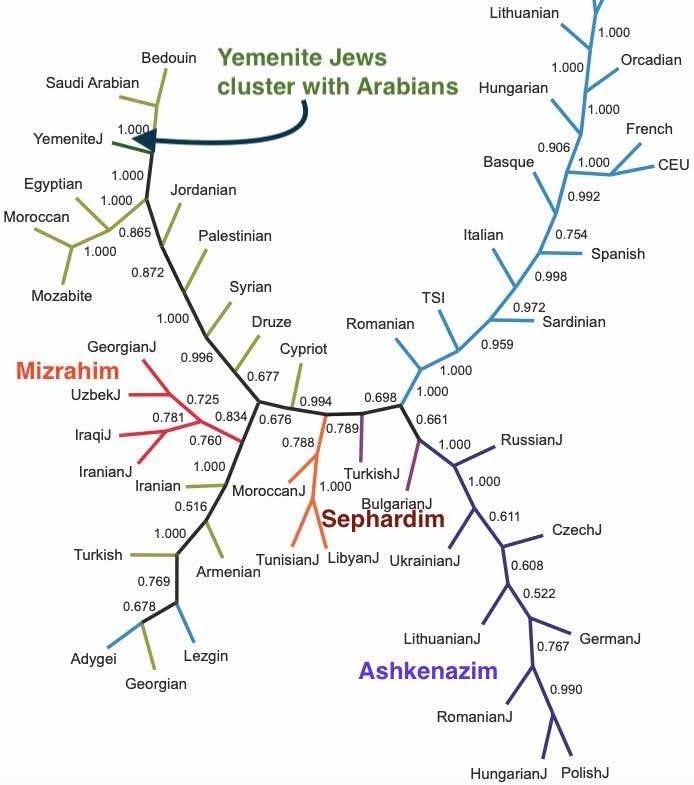

The eternal wanderers: Sephardic Jewish genetics and culture

The history and culture of Sephardic Jews, those who were expelled from Spain in 1492, are more complex than those of Ashkenazi Jews. But the past decade has seen the mysteries of their genetics and history unraveled, thread by thread:

Unlike the history of the Ashkenazim, the story of their Sephardic cousins is not a tight narrative. Both groups emerged from a synthesis of native Europeans and Levantine migrants, but after their early similarities, their paths diverged. After 1000 AD, the Ashkenazim exit the world stage before their grand cultural entrance in the 19th century. In contrast, the Jews of Iberia operated within a multi-religious landscape for centuries, engaging with and defining the broader public culture. One of these medieval Sephardic Jews, Maimonides, deployed a synthesis of Greek Aristotelianism with the ancient tradition of Jewish learning to construct a system of belief and practice that now serves as the benchmark of orthodoxy for Jews the world over, Ashkenazim and Sephardim both.

The drama of the 1492 expulsion, the persistence of crypto-Jews, and the Sephardic adventures across the Mediterranean inspired Benjamin Netanyahu’s father, himself Ashkenazi, to devote his academic career to the topic, writing the 1,400-page The Origins of the Inquisition in Fifteenth-Century Spain. While Ashkenazi Jews grew in number through natural increase, the Sephardim assimilated and influenced Jews in every corner of the world, leaving their mark on history through the attractiveness of their culture to others. Once limited to Spain, today the Sephardic tradition in the form of religious ritual and Hebrew pronunciation colors the daily life of populations from Morocco to Yemen to Iran, and of course Israel itself. The genius of the Sephardim transcends their genes and lives on in a patchwork legacy of customs, practices and traditions embraced in lands from the Atlantic to the Hindu Kush.

Heritability of height: the long and the short of it

Height is a socially and scientifically important trait. Tall men tend to be type-cast as leaders, and height clearly has benefits on the male side of the mating market. But for a geneticist, height is important because it’s a critical test case for how evolution can shape a trait over time given underlying genetic variation. Though we’ve always known that you inherit your height from your parents, today we understand it genomically due to the combination of sequencing and modern computational biology:

From the perspective of a geneticist, human height has long been known to be one of the most heritable of characteristics. There is clearly variation between families and populations, and being tall or short runs in particular lineages. Today we are finally arriving at a good accounting for height’s biological underpinnings and can pinpoint the genomic differences which account for this variation. As a trait that is subject to natural selection (albeit weak and variable), the average height of human populations has shifted upward and downward several times over the course of our species’ evolutionary history. There’s also a reason that men exaggerate their heights on dating profiles. Being tall isn’t just useful when it comes to playing basketball or spotting predators on a savanna, its fortunes have long been driven by sexual selection, at least in males (the majority of male American CEOs are over 6 feet tall, even though only 15% of the male general population is).

For scientists though, height has always been of outsized interest because it perfectly illustrates how genetics shapes and guides the variation and development of complex characteristics. What Drosophila has been to evolutionary genetics, height has been to quantitative genetics. Unlike single-gene diseases (cystic fibrosis, Tay Sachs and sickle-cell disease) or simpler traits (eye color, ear lobes and widow’s peak), human height is controlled by hundreds and thousands of genetic markers, and its impact on fitness is contextual and subtle (short people got plenty to live for, as it happens!). Now, with major advances in sequencing and computing, we are close to understanding the genetic basis of why you are tall or short.

I had a couple of main goals with this piece. The first was to trace the complexity behind a heritable trait with a profile like height. Think the complete inverse of the type of trait conventionally used to illustrate simple genetic concepts like recessive and dominant: say eye color or Gregor Mendel’s pea plant characteristics. There is a gene for the extreme stature of dwarfism, but otherwise, there’s no one simple “height gene.” And second was to tell the story of how the conundrum of height itself, and particularly its smooth (not disjoint) distribution of values in human populations… drove the genesis of an entire field we all take for granted today: statistics. We owe so many ubiquitous statistical methods to the early 20th-century drive to understand height specifically.

Also, if you missed the free post, please check it out:

Under pressure: the paradox of the diamond What obscure Jewish subgroups teach us about Ashkenazi and Sephardic flourishing

Podcasts

On the Unsupervised Learning podcast, my guests and I have drilled down on a broad variety of topics over the last month:

Alexander Young: everything you want to know about cognitive genomics

And here are the currently ungated podcasts all in one place.

First, Kat Rosenfield and Trent Colbert are very different people. Kat is a millennial woman who writes fiction and cultural commentary. Trent is a zoomer man attending Yale Law School. But we live in a common American culture and are subject to universal tensions, no matter our gender, age or race. Over the last decade, Kat has gotten caught up in the culture wars, and become a commentator on them from the perspective of a liberal who has resisted woke excesses. Trent recently became the target of a campaign at Yale Law School over an innocent email. Exactly the type of thing Kat might write about in one of her columns.

My conversations with Kat and Trent are attempts to explore where we are, and how we got here, as a culture. You may or may not be aligned with the changes in American politics and society, but they are going to impact you. Trent’s experience is a cautionary tale that even the most harmless and casual wording choices can explode into controversy, while Kat’s trajectory illustrates that an objectively mild rejection of objectively radical changes to norms and traditions can get you expelled from the “club.”

I don’t have any plans to turn Unsupervised Learning into a “Culture Wars” podcast, but now and then it’s useful to hear from guests who confront the constant stream of controversies that now define American public discourse.

Speaking of which, Josh Lipson and Alex Young touch on some of these controversies, in particular those relating to ethnicity, race and religion. Josh comes out of the world of amateur Jewish genetic genealogy, a description that belies the depth and richness of the knowledge of enthusiasts within the community. Josh and I talk about all the details of Jewish genetic history, with a focus on the Ashkenazim, what the science tells us now, and what it might be able to tell us in the future. This episode is a perfect complement to my post, Ashkenazi Jewish genetics: a match made in the Mediterranean. Josh knows his stuff, so we dive pretty deep.

Meanwhile, if you read my piece Should we get "woke" on genetics and behavior? or Dr. Kathryn Paige Harden’s The Genetic Lottery, I can recommend my conversation with Alex Young. He’s a young statistical geneticist working on traits like educational attainment. If you are a geneticist outside of this space, I highly recommend listening to Alex, because we get into the details of why and how he does what he does. It’s not junk science, it’s serious science, and if you insist on dismissing it, at least do yourself the favor of grappling with the actual ideas coming straight out of labs like these.

Then, I had Carole Hooven on to talk about sex and testosterone, evolution and biology, but we ended up spending a lot of time on the climate of intolerance for dissenting opinions in modern academia. Highly recommend T: The Story of Testosterone, the Hormone that Dominates and Divides Us itself, but I still maintain that the lengthy digression of the podcast is well worth a listen. We don’t have time to pretend people like Carole aren’t actively being purged right now on the flimsiest pretenses. Least of all those subscribers also still in academia.

Finally, I talked to Eric Berger about this book, Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days that Launched SpaceX. In a wide-ranging conversation that begins with the private space industry and Elon Musk, and touches on mining in the asteroid belt and O’Neill Cylinder Space Settlements, the closest fly-by we make with politics consists of discussing NASA’s prospects for the future. Eric’s passion for space and the technological frontier is infectious, and he reminds us that humanity can still do great things when we set our minds to it.

Reader comment

In The eternal wanderers: Sephardic Jewish genetics and culture a reader talks about the beliefs of the early-modern philosopher Spinoza, and how it related to his Jewish background:

The language Spinoza uses sounds pantheist because the Jewish community he was from had a panentheist conception of God. The name Yahweh is the causative form of the Hebrew verb for “to be”. Therefore, it can be interpreted as “causes to be”, “that which causes to be”, or causality itself. Keep that in mind, when you read Spinoza writing “That eternal and infinite being we call God, or Nature, acts from the same necessity from which he exists”. In the Kabbalistic conception of God, the Ein Sof is the one aspect of God that is not in some way synonymous with the universe. The Ein Sof is the infinite.

There are many correspondences between Spinoza thought and the writings of the kabbalist Abraham Cohen de Herrera. For example: “This oneness is described by Herrera as the nature of the Ein Sof, which would entail the view that everything is one in God and moreover that God is one inasmuch as he is infinite and many inasmuch as he manifests himself in being. In this view, the essence of the world is nothing other than the revealed aspect of God. As Spinoza would later argue in his Ethics, this God, i.e., the Ein Sof, therefore remains the immanent cause of all things. Assuming this pan(en)theistic view of the Ein Sof in the Puerta, Dunin-Borkowski adds that what the Kabbalists teach concerning the one-and-all is an age-old philosophical heritage. This is what Spinoza would have recognized in Kabbalah and referred to in a letter to Henry Oldenburg as a tradition of the ancient Hebrews that he acknowledges.”

The big difference between Spinoza and his community wasn’t regarding this conception, it was that Spinoza believed that which is called God doesn’t want anything, it just is.

Perhaps not that light…

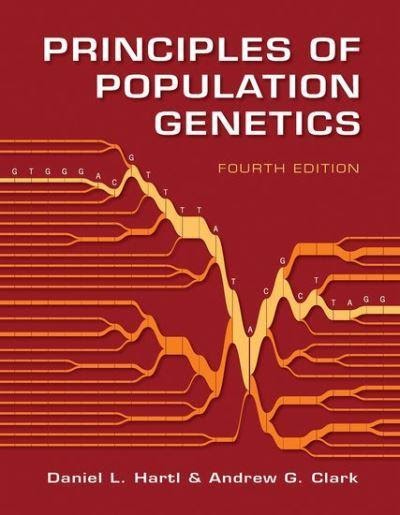

People often ask me how they can develop a bit of intuition in relation to population genetics. If they want a gentle introduction, I point them to John Gillespie’s Population Genetics: A Concise Guide. For 2021 “best practices,” Matt Hahn’s Molecular Population Genetics might be best. Finally, for masochists who also want books that can give them a workout, Lynch & Walsh’s two volumes, Genetics and Analysis of Quantitative Traits and Evolution and Selection of Quantitative Traits, fit the bill.

But for me, the Platonic ideal of a population genetics text remains Hartl & Clark, Principles of Population Genetics. I learned population genetics from the 3rd edition in the early 2000’s, and also have a copy of the 4th edition. It’s far more extensive than the Gillespie book, isn’t as intimidating as Walsh & Lynch, and probably is more relevant for the non-scientist than Hahn’s book.

To get utility out of Principles of Population Genetics you don’t really need to know much more than algebra, and it will provide you with the theoretical scaffold you need to really understand population genomics and its gusher of data.

Genomics Survey Time!

If you have a bit of time, I have 15 question survey for people in genomics. Trying to collect some information about the field in the beginning of the 2020’s.

Over to you

As always, I welcome paid-subscriber comments and your reading recommendations and suggestions. They never disappoint.

+1 for all Persian rice dishes. Cherry rice is my favorite.

Highly recommend anyone who visits Florida check out a rocket launch if they can. Night launches are pretty spectacular. Launches near sunrise and sunset can also be something to behold and will leave trails effecting the coloring in the sky.