Our Three-Body Problem

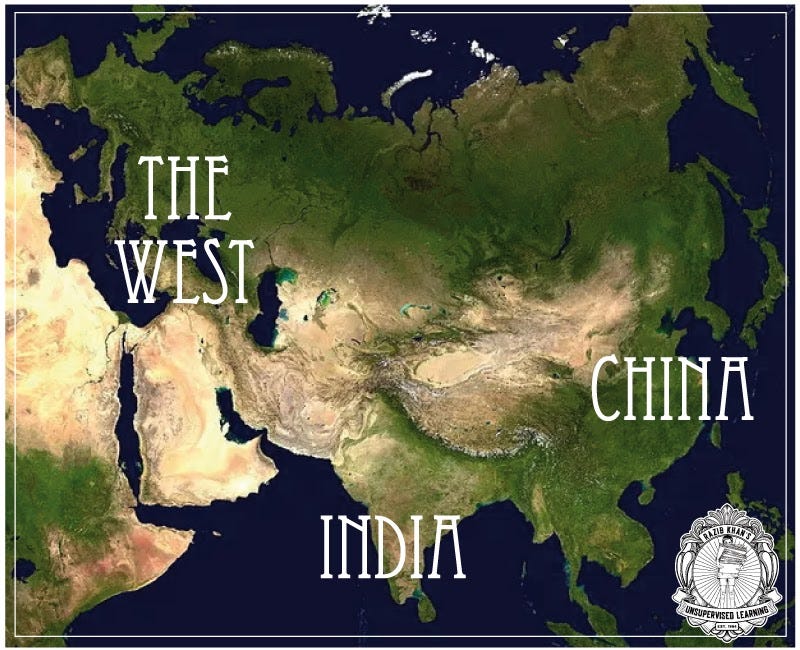

China, India and the Rest

In my daily life, I spend a lot of time up to my eyeballs in direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic results. The American consumer might often be looking to DTC companies to tell them in great detail how much say, German vs. French ancestry they carry. But as many bloody wars have been fought and as many millions of lives cut short the last few hundred years over these deadly serious borders, our genes aren’t persuaded. Results no more specific than “Broadly Western European” are hardly the rousing call to rediscover their roots people crave, but as far as our genes are concerned, it’s often as good as we’re going to get. European citizens can readily inventory the incomprehensibility of their nearest neighbors’ language, their mystifying traditions, their suspicious preferences in alcoholic beverages, the blasphemous divergences in their confessional traditions, etc. etc. But in many cases, it really is all a veneer. Give me these various nationals’ whole genomes, and at the genetic level, I often won’t be able to point you to any serious distinction. In many cases, I truly can’t tell you which are, say French as distinct from German at all.

This narcissism of small differences reminds me at times of a similar tunnel vision I’m discerning more and more in realpolitik as our 21st century unfolds. It’s understandable that the cloud of the 20th century’s convulsive European wars casts a long shadow over our world view 100 and 70 years on. No surprise either that Europe and the US’s last two decades of horror grappling with a nihilist strain of Islam in their midst (an internecine struggle I see reliably waxing and waning like sibling rivalries over the long sweep of history) throws a West v. Islam contrast into greater relief than perhaps warranted.

I would instead submit that we’re well on our way to a tri-polar world where all those 20th and early 21st-century foes actually collapse into a single sphere characterized more by its deeply intertwined roots than tiny distinctions among its branches. Instead, the greatest contrasts I foresee the world grappling with in decades to come include the deep differences among the two cultural giants who effectively sat out the global 20th century. And not just each of their distinct contrasts with the West.

“The West and the Rest” has an irresistible ring, but when you get down to it, the incommensurability of Indian culture to that of China yawns just as unfathomably, or more so than that between the West and either Asian giant. For my money, the irreconcilable cultural poles the remaining century will bring into focus are these three ancient traditions: the broader Abrahamic West, the Chinese sphere and the Indian one.

A global world fractured by history

We live in a globalized world. But our hyperconnected landscape has notably not produced a flat homogeneity of values. India, China and the West, which encompasses Christian Europe and the Muslim Near East, continue to serve as distinct and unique cores of human civilization. These three great pillars of human tradition reflect profoundly different values and orientations in their elite cultures. We have pragmatic China, philosophical India and a broader West threading a path between the two. Most remaining civilizations can easily be understood as both derivative and a synthesis of these traditions. Latin America is broadly Western, with indigenous American and African elements. Southeast Asian nations balance Indian, Chinese, Islamic and indigenous influences. In the 20th century, the hegemony of Europe was so overwhelming that Indian and Chinese elites adopted Western political ideas and institutions, whether those were liberal, democratic socialist or Marxist-Leninist. Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, was culturally a product of the British elite. Mao Zedong strove to incinerate ancient Chinese culture. He saw himself as a Marxist revolutionary completing the long march of history out of the Asiatic mode of production. The Indian and Chinese future was Western, albeit with better banquets.

But in the 21st century, a great rebalancing toward Asia (already over half the worlds’ economy and on pace for 60% by 2030) is due. Narendra Modi, the current Prime Minister of India is a Hindu nationalist who emerged from that nation’s vast lower middle class. Xi Jiping is likely to be the last leader of the People’s Republic of China to have lived through the Cultural Revolution as an adult. Western institutions dominate the world in forms of government and legal systems. But their deeper meaning is often hollow. Algeria, Bangladesh and China each refer to themselves as a “People’s Republic,” a relic of 20th-century Communism, despite being very different nations with little connection to the term’s ideological source. Xi’s China is led by a party that calls itself Communist and claims to enact a dictatorship of the proletariat, but in reality, it is a pro-corporate authoritarian oligarchy. As deep cultural differences that were sublimated in the 20th century’s ideological fervor resurface, Samuel Huntington’s prophecy that 21st-century geopolitics may fracture along civilization lines now looms up again.

The great traditions of the Iron Age

The core differences go back at least 2,500 years, and they date to German philosopher Karl Jaspers’ “Axial Age,” when the seeds of the great religions and transcendent philosophies were sown. Confucian thought in China preoccupied itself with the well-being and virtue of people in this life. China’s metaphysical tradition was stimulated by Buddhism, which arrived already philosophically mature from India.* Instead of reflecting on the nature of the universe, the Chinese recorded the events of this world in exact detail. The Zhou defeated the Shang on the 20th of January 1046 BCE, thus beginning classical Chinese history.

Meanwhile, Indian intellectual energy was so focused on abstract metaphysics that the subcontinent developed no native historical tradition at all. Instead, Indian ascetics retreated to the forests and produced the contemplative Upanishads, which plumb the depths of inner mysticism. This single-minded devotion to the inner world left little time for the outer world. India’s historical chronology is in fact calibrated by the pilgrimages of Chinese monks to Buddhist holy sites in the subcontinent. There is no Indian Herodotus, but there are Faxian and Xuanzang.

Finally, the Western tradition began with Egypt and Mesopotamia, matured with Greece, Rome and Persia and grew to encompass the dual Abrahamic civilizations of Christendom and Islam. The West exists at an equipoise between the practical and the abstract. Aristotle’s own oeuvre alone encompassed both Politics and Metaphysics, underscoring that the concrete and ideal were both fully allowed to vie for centrality in Western civilization. During the Enlightenment, Western thinkers looked to the secular governing elites of Confucian Imperial China, while in the 19th century, philosophers like Schopenhauer drank deeply at the well of Indian thought in formulating their ideas.

Such connections and influences have always existed. And that is all to the good. The late historian William H. McNeill in The Human Web: A Bird's-Eye View of World History posited that the past 5,000 years have been characterized by a growing interconnectedness across human societies. He argued the connections fortified human civilization against the specter of systemic collapse. While Western Europe slunk through the depths of its Dark Age after the fall of Rome, Tang China saw its cosmopolitan peak. Europe’s 19th-century conquest of the world was only possible because medieval China had kept the lights on 1,000 years earlier. While illiterate European warlords extracted “protection money” from their subjects at the point of the sword, the Chinese were innovating with gunpowder and inventing paper money..

Some might quibble with bracketing Islam and Christian Europe, or ancient Greece with Egypt and Persia, as part of the “West.” But it was the rise of Islam that fractured the world of Late Antiquity, united around the Mediterranean and stretching from Arabia to Scotland. North Africa and Syria produced Roman Emperors. Britain did not. “The West” in modern parlance is a secularized form of the archaic “Christendom,” but Christianity and Islam operate within the same metaphysical universe and partake of a shared history. Christians and Muslims both worship the same God revealed to Abraham. They have a truly shared understanding of what a religion is, though they might fight to the death over abstruse matters of theology.

Islam and Christianity both draw on Hebrew religious ideas and Greek philosophical traditions. Both have been strongly shaped by Persian Zoroastrian concepts of good and evil, heaven and hell. The angels who serve the Abrahamic God are imported from Zoroastrianism, as are the ideas of the bodily resurrection and the end of days. West of the Indus river, and north of the Sahara desert, the peoples of Europe, North Africa, and West Asia may have been fractious and seen themselves as enemies, but ultimately they spoke one cultural language.

All under heaven

It is in religion that some of the most striking distinctions between the three great civilized traditions emerge. In the West, God is a being separate from his creation, revealed through prophets. India’s dominant religious traditions view God as an immanent being, whose essence suffuses the universe and manifests in all things. Such extensive theological inquiry into the nature of the supernatural has been of minimal concern in China, where maintenance of traditional rites as an instrument toward proper human governance and flourishing monopolizes the spotlight.

Chinese, Indians and Westerners have different views on religious identity. When Roman Catholic missionaries began converting Chinese in the 16th century, they noticed some of the new Christians continued to engage in ancestor worship and visit temples to local gods. New converts explained that they found Christianity congenial, but saw no reason to give up their other practices and beliefs. This is in keeping with the Chinese concept of “three teachings”, Buddhism, Daoism and Confucianism forming a seamless whole. Many Chinese partook of all these religions, and also continued to venerate their ancestors and patronize regional gods. In the Chinese view, Roman Catholics brought a new religion, which they could add to the ones they already had.

If China was practical, India again was philosophical. Gandhi outlined the Hindu view succinctly when he stated that religions “are different roads converging to the same point. What does it matter that we take different roads so long as we reach the same goal?” The Hindu God was immanent in the whole universe. And all religions and all things partook of the divine. While the Chinese accumulated individual religions, Indians absorbed religious ideas and integrated them into Hinduism.

The West came to a very different understanding. God tells the Hebrews that “Thou shalt have no other gods before me.” Jesus tells his followers that “I am the way, the truth, and the life: no man cometh unto the Father, but by me.” The first pillar of Islam, the profession of faith, states that there “is no God but God, Muhammad is the messenger of God.”

Traditionally the Chinese did not have a single religion, but visited Buddhist monks and Daoist priests as need arose. They venerated Confucius and his teachings as guides to the good life, not as a path to salvation. Those with devotion to a particular sect, such as Pure Land Buddhism, were the exception, not the rule. In contrast, elite Hindus understood themselves to be followers of Sanatana dharma, the “great tradition.” But the details of their particular belief were left to individual choice and preference, with adherence to various philosophical schools.

In contrast, Muslims, Christians and Jews had exclusive identities and mandatory beliefs. This Western view of religion was deeply incomprehensible to the Chinese. Christians in China have repeatedly been mistaken for a sect of Pure Land Buddhism, a movement devoted to the cult of the Bodhisattva Amitābha. Through worship and praise of Amitābha, devotees aim to be reborn in the heavenly Pure Land. All Western religions seem to get misidentified at some point as Pure Land Buddhism by the Chinese. This occurred with the obscure Iranian Manichaean religion, which gave rise to the White Lotus Buddhist movement. Persian Christianity in China was subsumed into Pure Land Buddhism 1,000 years ago. And when Roman Catholics arrived more than 400 years ago from Europe, the religion was again confused with this sect, to the missionaries’ chagrin and irritation.

China was not alone in its incomprehension of the West. When Muslims first arrived in the Indian subcontinent, the natives referred to them as Yavannas. This term denotes Western foreigners, and derives from “Ionian,” as in: Greek. Though Arabs and Persians are clearly not Greek, from an Indian perspective, these three groups shared much more in common than not. Only in India does the ancient Greek Galenic medical tradition survive, the Yūnānī school. Muslims transmitted this school from the West to India after 1200 AD, where it survived and flourished long after dying out in its homeland. This is a case where India’s integrative instinct, culturally appropriating from another tradition, preserved ancient knowledge while openly acknowledging its origin. In contrast, indirect Indian influence on Christianity through Neoplatonism or the modeling of Muslim madrassas on Buddhist viharas are appropriations uncredited and unknown. Where India absorbs and integrates, the West consumes and digests.

It is notable in William Dalrymple’s White Mughals: Love and Betrayal in Eighteenth-Century India that Europeans who assimilated into Indian culture in the 18th and early 19th century more commonly converted to Islam than Hinduism. A monotheistic religion was more accessible to Westerners, something explicitly asserted by the reactionary 20th-century French philosopher René Guénon, who studied Hindu Advaita Vêdânta, but ultimately converted to Islam (he argued that religious truth had gone extinct in Europe due to the secularization of Christianity).

Meanwhile, Muslims and Christians often did not know how to interpret the plethora of sects and traditions in the east, whether in India or China, and frequently dismissed them all as “idolaters,” marking them off from the Abrahamic traditions. Islam explicitly divides humans into three classes: believers, the tolerated “People of the Book” (Jews and Christians) and finally, kafirs, those who reject the Abrahamic God and must be converted by force. Though Christians sometimes referred to Muslims as heathens, there too, on the whole, the term was generally reserved for practitioners of paganism, by which they meant Hinduism, Buddhism and those who practiced ethnic religions like Shinto. East-west incomprehension spawned some farcical misunderstandings. When Vasco da Gama and the Portuguese arrived in India in 1498, they did not understand what Hinduism was, and assumed that Brahmins were Catholic priests. They initially saw Indian idols to be forms of their own religious statuary. Though they soon recognized their mistake, the episode illustrates how parochial European thought was, too inelastic to stretch beyond Christianity, Islam and Judaism.

Chinese pragmatism towards religion manifests itself in the diaspora. In Thailand, the Chinese have traditionally become Theravada Buddhists, in the Philippines, Roman Catholics. In the United States, the largest faction is Protestant. The exceptions here are Malaysia and Indonesia, where the Chinese have not converted to Islam. The rationale reflects one of the only human loyalties that truly vies with religion: culinary folkways; the Islamic ban on consumption of pork would be deeply disruptive to Chinese culinary tradition. In modern China, converting to Christianity doesn’t alienate a person from their Han ethnicity, while conversion to Islam is actually perceived as a conflict, thanks to Islam’s insistence on a host of practices which conflict with traditional Han norms.

Purity and pragmatism

In contrast to Chinese pragmatism, Indians tend toward an esotericism that expresses itself with a focus on ritual purity. Traditional Chinese cuisine’s signature omnivorousness stands in sharp contrast to the subcontinent’s punctiliously abstemious tendencies. Though most Indian communities are not vegetarian, native Indian elite opinion has been strongly supportive of vegetarianism. Modernization has been enabling the spread of the ideal. Bans on the consumption of beef are a political issue in India. Hindu conservatives aggressively protect animals, in particular cows. Vegetarianism is justified on individual grounds of health and cultivation of compassion, but also due to the principle of nonviolence being applied to animals, who are clearly different, but seen to express the divine essence that pervades the universe.

In contrast, China does not even have an animal protection law. Though there is a native Daoist tradition of compassion toward animals and Buddhism fosters a vegetarian culinary tradition, the Chinese instrumentalist view of animals could hardly be more at odds with India’s: they are food, medicine and material. In fact, dogs are customarily killed painfully in China because it is believed that the rush of adrenaline makes their meat more delicious.

Not surprisingly, Western views have been more mixed. Unlike in Indian thought, Western religions have emphasized the separation between humans and animals, with the former alone having souls. In Genesis, God proclaims that “Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you...” But he also enjoins humanity to be stewards of the earth, and St. Francis of Assisi models Christian compassion toward animals. Islam’s halal slaughter practices are also geared toward minimizing cruelty. Animals may not have souls, but rather than dismiss them as purely biological utilities, they are acknowledged as conscious creations of God.

Synthetic civilizations

Civilizational influences matter in areas outside core zones. Vietnam and Myanmar are both Southeast Asian. But Vietnam has felt China’s influence much more decisively, while Myanmar’s culture reflects its adherence to Theravada Buddhism, an arrival from India. The Vietnamese are religiously pragmatic, like the Chinese, while the majority Burman ethnicity in Myanmar are so tied to Theravada Buddhism that they view themselves as the custodians of this tradition. Despite having a much longer Buddhist tradition, Sri Lankan kings have repeatedly pleaded for Burmese monks to come and revive the religion on their island when it fell into decay. The ethno-religious strife in modern Myanmar between Buddhists and Muslims is eerily similar to that in the Indian subcontinent. In this conception of derivative and synthetic civilizations, much of the post-colonial world of Africa must be thought of as an outgrowth of the West. Latin America, similarly, is fundamentally Western. Obviously, there are deep indigenous cultural layers in both spheres, but this was also true when Christianity spread to Northern Europe, and Islam to Indonesia. Local differences do not erase broad civilizational affinities and identities.

The rise of the South and the East

As we proceed deep into the 21st century, American hyperpower is fading. Europe and North America are riding a demographic decline straight down out of prominence. Meanwhile, Latin America and Africa will carry the Western torch onward with their demographic dynamism and growth. More Christians already live in Africa than on any other continent. The moment in the late 20th century when anyone could plausibly argue the global Western order would erase all substantive differences has passed. China’s Communist regime now sponsors “Confucius Institutes,” and a Hindu nationalist party is dominant in India. These two distinct Asian societies are emerging out of their centuries of humiliation and weakness. The CCP’s foreign policy realpolitik expresses Chinese pragmatism. The Chinese seek allies who can provide them with raw materials, not fellow travelers in a global ideological revolution. Indian idealism expresses itself in the rise of vegetarianism in a nation whose growing wealth could actually enable a great increase in meat consumption. Even if they are pseudoscientific, the persistence and resurgence of Indian and Chinese traditional medicine highlight the tenacity of ancient folkways in the modern world.

The Axial Age is long past. Literate civilization is the rule on our planet. Connections between the ancient civilizations were much more tenuous. Today, inter-cultural interactions are ubiquitous and pervasive. This makes it more, not less crucial to understand the deep differences between societies. Conflict and cooperation have always occurred, but now they are the rule, not the exception. The “human web” is tightly knotted, and we share a small and fragile planet. It is more urgent now than ever before that we understand each other across our civilizational chasms.

* Religious Daoism exhibited strong influences from Buddhism, and in its turn shaped some sects of Buddhism, such as the Chan tradition, called Zen in Japan.

Brilliant Razib!!! Loved this line "Where India absorbs and integrates, the West consumes and digests."

Good article, though I do find this part a bit unsatisfying:

"Only in India does the ancient Greek Galenic medical tradition survive, the Yūnānī school. Muslims transmitted this school from the West to India after 1200 AD, where it survived and flourished long after dying out in its homeland. This is a case where India’s integrative instinct, culturally appropriating from another tradition, preserved ancient knowledge while openly acknowledging its origin. In contrast, indirect Indian influence on Christianity through Neoplatonism or the modeling of Muslim madrassas on Buddhist viharas are appropriations uncredited and unknown. Where India absorbs and integrates, the West consumes and digests."

I do not find these examples very good comparisons. You use a theological comparison for Christianity and Islam, then for lack of a better term, materialistic knowledge for Hinduism. Is there an example where you could compare how Hinduism acknowledges and "integrates" theological concepts from other religions? To the counter of the example of the theoretical unacknowledged Hindu influence on Christianity, there have been some scholars who say there was a theoretical unacknowledged "Christian" influence in Hinduism during the height of the Bhakti movement/era in South India due to the Nestorian Christians living there. The Hindu example you use of "integration" (as opposed to the consuming) seems a more physical/practical knowledge, i.e. medicine. Greek medicine system may have even reached earlier to India via the Indo-Greek kingdoms, then when Muslims encountered India, it further reinforced that medical knowledge being from the "Greeks". But why is that surprising that Hindus would acknowledge their practical knowledge from where they feel it originated? This is not to cast anyone in a bad light, if anything instead of integration, I think it just shows great scholarship on Hindus to document where they feel the knowledge came from. Hindu Indians were collaborating across the middle east with other scholars in the pursuit of knowledge, first with the Zoroastrian, Manichean, and Nestorian Persians, possibly the Greeks, and then later with the Muslims in the "House of Wisdom" You say Hinduism gives credit to the medical knowledge, but records in the west and the Catholic church openly acknowledged their knowledge received from the "pagan" Greeks, and later the western "enlightenment' acknowledges their gleaning knowledge from contributions of the Islamic medical scientists, Another example, I could be wrong, but I think there are Islamic records of gaining knowledge from Hindus/India, for example what the West used to call "Arabic" Numerals, the Islamic world called "Hindu" numerals. Even the great Patriarch of Nestorians, Timothy, mentions the origin of numbers from India. Great article Razib, a lot to think over, but just this one part I feel examples with more direct comparisons, i.e. theology to theology, just would make the point better.