Our African origins: the more we understand, the less we know

Part 2 of 3: The revolution in our understanding of African human evolution

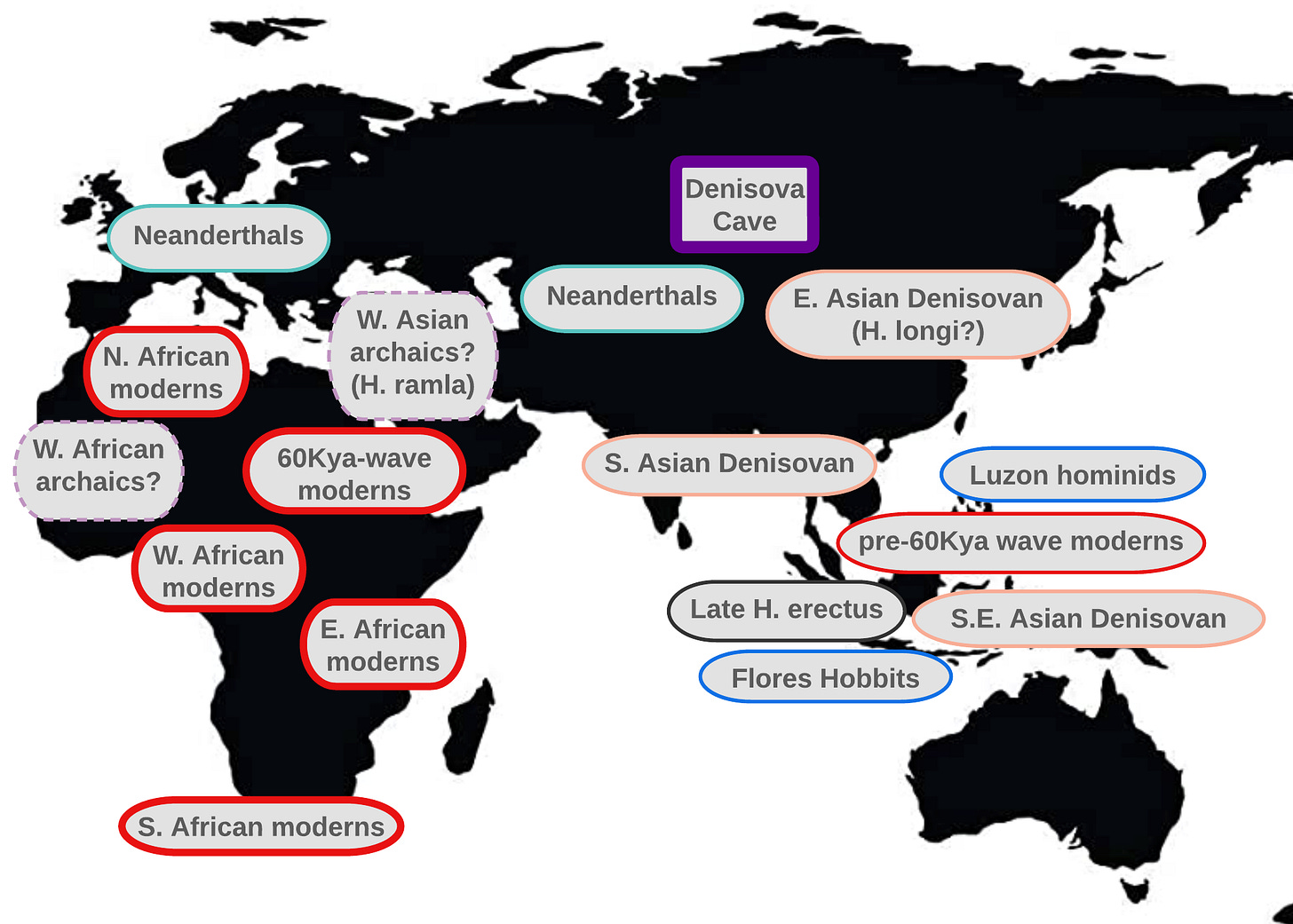

Other posts in this series: Yo mama's mama's mama's mama... etc. and What happens in Denisova Cave stays in Denisova Cave... until now.

In 2004, a fossil from a site in Ethiopia called Omo Kibish, was definitively dated to 195,000 years ago. These remains had been known since the 1970’s, and were the long-time candidate for the oldest known set of anatomically modern human remains. The skull looks like an ordinary one you’d see in a biology classroom today, not the more robust skulls of earlier African hominids and Neanderthals. The 195,000 years ago date was important because it roughly aligned with mitochondrial Eve, and was in the same range as Y-chromosomal Adam. With the Omo fossil in hand, by the mid-aughts paleoanthropologists were bringing together different lines of evidence to produce a compelling case that modern humans arose in East Africa 200,000 years ago. Some of these East Africans eventually left the continent at least 60,000 years ago, replacing our robust European cousins, the Neanderthals. In this telling, as the descendants of Omo’s people migrated north and east, they also pushed south and west within Africa. It was a neat and tidy narrative of the human past. One tribe, one epic expansion.

The end of the old order

In 2017, this simple story with Omo as a fossil linchpin fell apart overnight. Archaeologists in coastal Morocco, all the way in Africa’s far northwest, uncovered a fossil dating to more than 300,000 years ago that was poised on the precipice of anatomical modernity. Chris Stringer has described it to me as a proto-modern skull, well on the way to becoming “like us.” The discovery of the skull was a bombshell, a media sensation prompting headlines like “Oldest Fossils of Homo Sapiens Found in Morocco, Altering History of Our Species” in The New York Times. Its appearance in Morocco, at a site called Jebel Irhoud, was totally unexpected, and East-African Omo had to immediately concede its longstanding pride of place. The fossil at Jebel Irhoud was over 100,000 years older than the one at Omo Kibish, clearly, an earlier antecedent of modern humans that was confoundingly far from the putative East-African hearth. To many paleoanthropologists, such a surprising find made plain that their understanding had fallen short; they needed to reevaluate. Philip Gunz, an author on one of the Jebel Irhoud papers declared flatly that “We did not evolve from a single ‘cradle of mankind’ somewhere in East Africa.” A major assumption of our solid old out-of-Africa theory: a singular origin of modern humanity, and definitely an East African one, was now in tatters