Made in China

Does it matter who writes history if no one reads it?

As tedious as it grows with repetition, I’m afraid the old Santayana chestnut that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it” remains no less incisive in our amnesiac age. Data and infinite information might be at our collective fingertips, but who do we depend on to judiciously tend them? Who makes it their mission to remember dispassionately, to carry forward truths both flattering and inconvenient? Who among us actually knew in the first place? Perilously few, in my experience.

I recently witnessed a scholar informing his audience that Xi Jinping’s genocidal inclination towards the Uygurs distinguishes his regime from its Imperial Chinese forerunners who displayed no such maniacal tendencies, despite their cruelties. I objected that on the contrary Imperial China had been the author of multiple genocides of subject peoples over the millennia. He ignored me. A bystander to the conversation argued that Sinologists tend to be quite pro-China, so no one spotlights these awkward truths. He probably didn't know.

Many would argue that we’re already deep into a post-fact era and the battle to actually remember anything but the blandest contours of our few millennia of human history has long since been ceded to a postmodern elite obsessed with facile disputes over race, victimology and their own most immediately accessible personal feelings. They’re probably right. But I find it hard to care. I’m too disagreeable and I owe too many of my intellectual debts and loyalties to humans whose time on earth never overlapped mine anyway. I can’t bend myself to the vapid ethos of this ahistorical age I happen to live in. I remember and remember and remember. It’s probably no use, but it’s what I do.

You’re here reading me, so odds are, you do, too. Many among the 1.4 billion humans behind the Great Chinese firewall defied censors to mourn an early Covid coverup whistleblower’s death, gathered for hours clamoring for any insight about their government’s pogroms against the Uygurs when a tiny door briefly opened on Clubhouse, and struggle futilely to know anything surrounding the 1989 events of Tiananmen Square or a thousand other moments unflattering to the Chinese regime’s self image. But us? We do it to ourselves. No one’s surveilling us to keep us from reading or remembering. We do it to ourselves.

I have a dread suspicion this post, what should be a banal little act of recollection, will become a recurring feature on this Substack. Perhaps it’s a necessary role in an age of atrophy... scattering these occasional little oases of factual recollection across an arid landscape of righteous amnesia? All in hopes that the wiser inhabitants of some future age might hopscotch their way back to storehouses still packed with the millennia of human memory, fact and reflection we largely ignore.

The Forgotten Genocide

Today there are twelve million Uyghurs in a nation of 1.4 billion Chinese, a fraction of a voiceless percent. The Chinese have imprisoned whole communities and are persecuting Uyghurs en masse. Reeducation camps, a tried and tested instrument in the toolkit of Communist societies for a century, dot Xinjiang today. Islam and the Uyghur language are called threats to the regime. Mosques are monitored. Children are consigned to Mandarin Chinese language schools. The Chinese Communist Party is executing a slow-rolling genocide.

How can we understand this? We could look back to history. But that presupposes we know any.

Too often, today’s commentators lack the most basic familiarity with the lineaments of the Chinese past, even though it is copiously documented. Absent that basic knowledge, they make recourse to abstractions of European colonialism or lazily ascribe the inspiration for the current horror to Hitler or Stalin. They construe the actions of the Chinese purely in the light of Western history because that is the only interpretative lever they can operate.

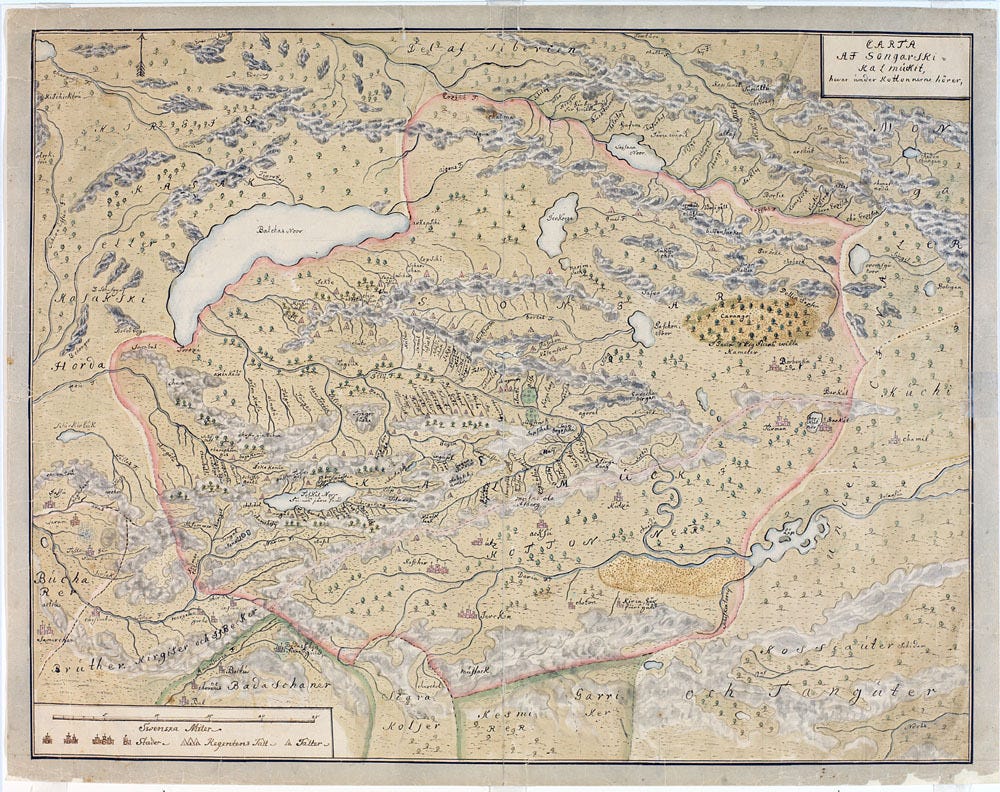

The reality is that Chinese history itself offers a clear example of genocide and repression on a mass scale to “fix” a political problem: the genocide of the Dzungar Mongols in the 18th century. This occurred in the northern half of today’s Xinjiang: Dzungaria. Dzungaria was a territory named for a people who have since been ethnically cleansed from it. The genocide of the Dzungars reminds us that the template for government-sanctioned repression and violence of an ethnicity requires no Western influence. It is a feature of Chinese governance and has been for centuries.

The Dzungar Khanate was the last of the great steppe empires. Less storied than the Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan and the Turkic Empire of Tamerlane, it is now notable for the genocide that accompanied its destruction. After the Dzungar Khanate was erased, modern China’s borders gained their final outline. This act concluded the geographical invention of China as we know it today.

The Great Enemy

For nearly 2,000 years, the empires of the steppe menaced the settled societies to their west, east, and south. Attila the Hun threatened the Romans, the Turks plundered northern India, and China was overwhelmed many times by horsemen from the north. But by the 1600’s, new weaponry had evened the playing field. The “gunpowder empires” could slowly strangle the tribes of the open steppe, one canon volley at a time.

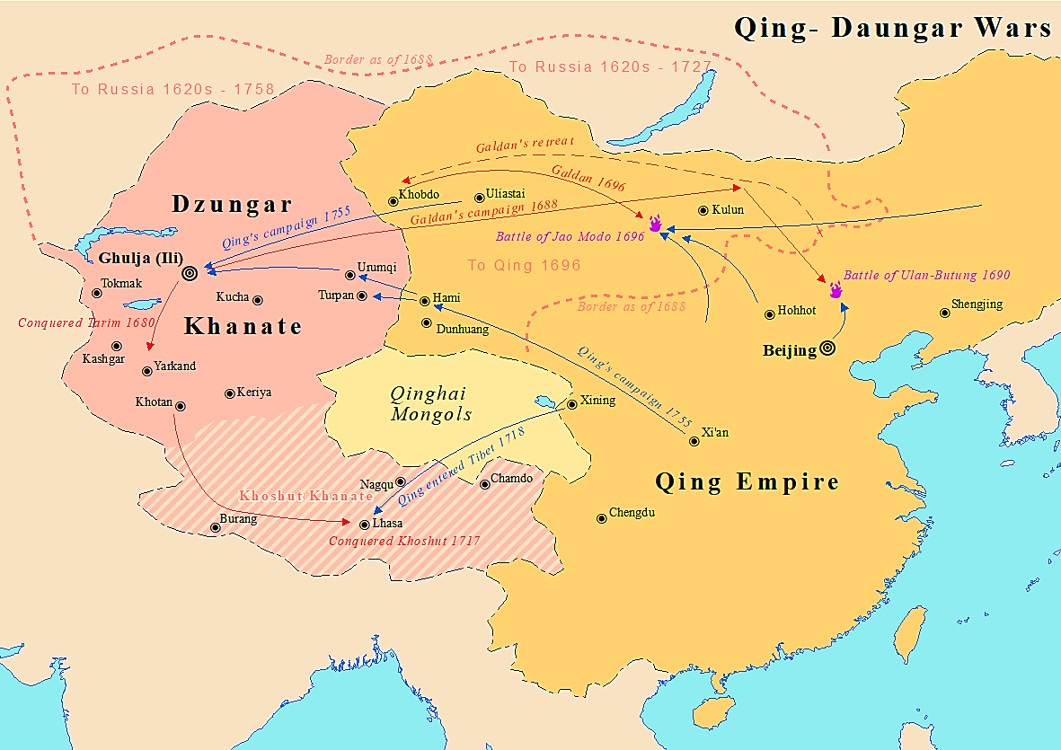

Squeezed ever more tightly between the rising powers of Tsarist Russia and Manchu China, the ultimate demise of the Dzungar Khanate was achieved through the genocide of the constituent tribes. Between 1755 and 1757 80% of the Dzungars died or were killed through the concerted action of Manchu-led forces, ending centuries of conflict and decades of rebellion. Dzungaria, the northern half of modern-day Xinjiang, was thus emptied of Mongols and resettled with Kazakhs and Uyghurs.

The official modern definition of genocide includes “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.” Manchu authorities issued official orders and exhortations to attempt total extermination. A non-European power committed this act long before the modern era. Genocide requires no connection to European ideologies of colonialism or the lethal force of machine guns.

The rise of the Dzungars

The Dzungars were not only the last of the Mongol Empires, they were also marginal Mongols. The Dzungar confederacy was a fusion of the Olot, Torghut, Dörbet and Khoshut tribes, collectively called the Oirats. During the time of Genghis Khan, the Oirats were forest-dwellers, on the southern edge of Siberia, not part of the nomadic societies to their south that joined the Mongol horde. They did not share in the glory of the conquests. Ethnically, Dzungars who survived the genocide remain distinct from the majority of Mongols who were ruled by descendants of Genghis Khan, the Khalkha Mongols.

Between the 14th and 18th centuries, the Oirats were often at war with the Khalkha Mongols. The Khalkha had prestige and legitimacy on their side. The Oirats had the fact that they were hardier, tougher, and their elites less exposed to the comforts of wealth. In other words, the Oirat advantage over the Khalkha Mongols was the advantage the Khalkha Mongols had once had over their enemies.

By the end of the 17th century, the Oirat tribes who had become the Dzungars gained the upper hand. In 1691, the Khalkha Mongols forestalled surrendering to the Dzungars by submitting themselves to the new rulers of China: the Manchus.

The rise of the Manchus

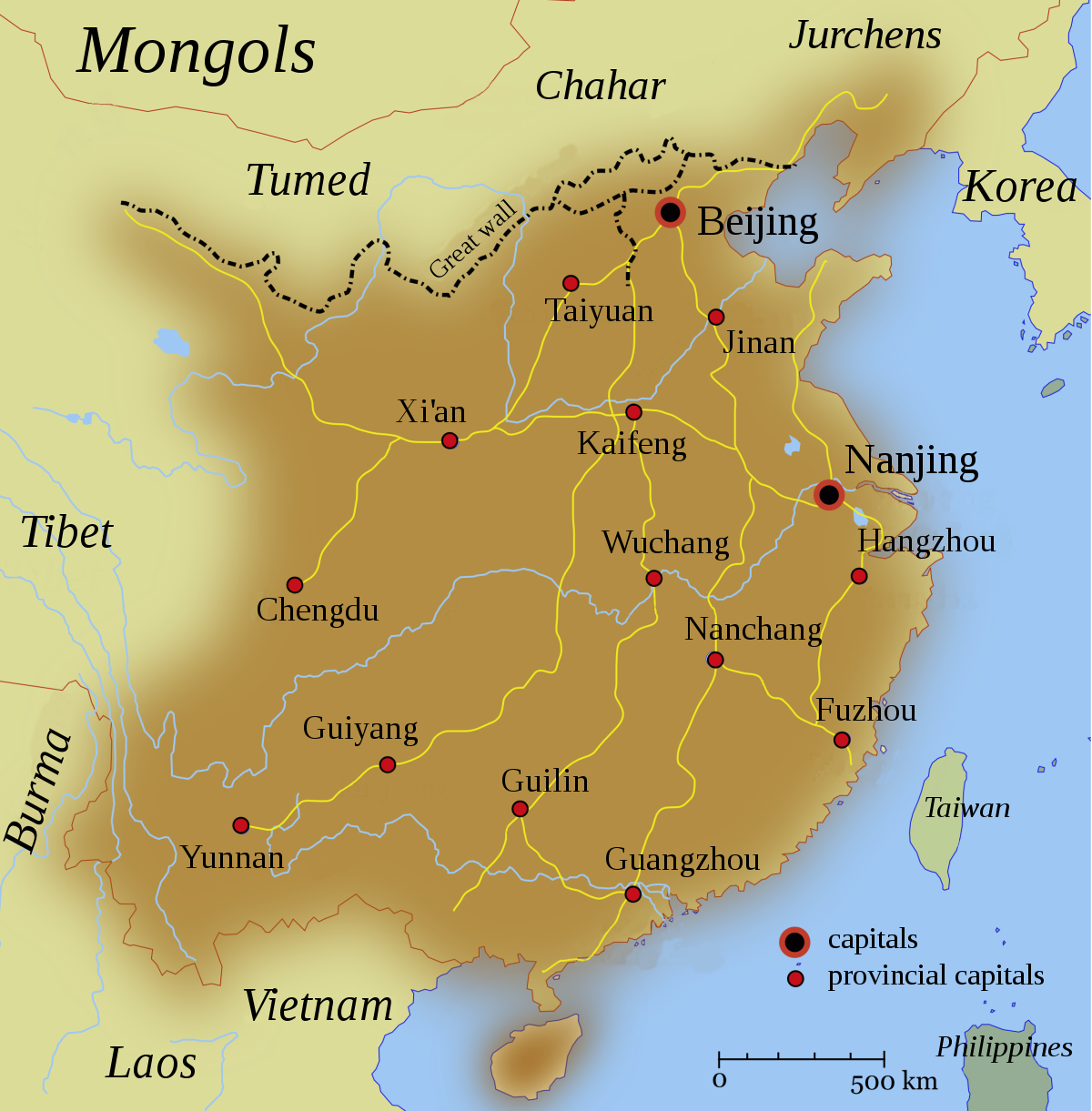

The Manchus were a coalition of tribes that occupied the forest zone to the east of Mongolia, what we today call Manchuria in northeast China. The Manchus understood empire and conquest. Between 1115 and 1234, their ancestors, the Jurchen, ruled northern China as the Jin dynasty. That dynasty was destroyed by the Mongol invasion from the north.

In the subsequent centuries, the Jurchen tribes reinvented themselves as the Manchu, and established alliances with the Khalkha Mongols, in their ancient home of Manchuria. In the mid-17th century, the collapse of the Ming dynasty presented another opportunity. Between 1644 and 1659 the Manchus conquered China. Within the borders of Imperial China, they ruled as Chinese Emperors, founding the Qing dynasty. Emperor Kangxi reigned as an exemplary Confucian monarch between 1661 and 1722, and his six-decade regime helped inspire a wave of early-Enlightenment Sinophilia in Europe. China embodied to many of the philosophers of the age the possibility of secular, enlightened despotism administered by rational bureaucrats.

But there was another side of the Qing: outside of the borders of the Chinese heartland they were Manchurian warlords. Kangxi devoted multiple months of the year to hunting, a pastime of the steppe and forest zone, not an avocation typical of Chinese Emperors. Unlike native Chinese, the Manchus had a deep relationship to Tibetan Buddhism, which led to the Manchu absorption of Tibet into their domains in 1720.

The Manchus had assimilated to many of the folkways of the steppe. They were comfortable with the culture of the nomads to their west. The Khalkha Mongols were an essential part of the Manchu military class. In the 19th century, Mongol generals played a role in suppressing rebellions in China proper.

Manchu entanglement with Tibetan Buddhism and the Khalkha Mongols made conflict with the Dzungar tribes inevitable. The Manchus stood between the Dzungars and their ambition to bring together all the Mongol people under their leadership. In the centuries after the decline of the Mongol Empire, the scions of Genghis Khan had become habituated to a certain level of luxurious living which left them less ferocious fighters than their lean and hungry Dzungar cousins. Over the centuries, the Khalkha had lost ground to the Dzungars. On the eve of their abrupt pivot to an alliance with the Manchus, there was no viable independent path forward between the two rising powers.

Both the Manchus and Dzungar were devotees of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dzungar interference in the affairs of Tibet was alarming to Manchu rulers who cultivated and relied upon the legitimacy of Buddhist Lamas.

After their conquest of China, the Manchu had men and materiel beyond the wildest expectations of any steppe warlord. They went into the conflict with enormous advantages.

A rebellious people

The Dzungar Khanate was a predatory steppe polity. Unlike the extensive bureaucratic states emerging on the fertile edges of Eurasia, the steppe produced societies that were more often simply a collection of tribes bound together by personal loyalties. In this way, they were primal, ancient throwbacks to something deeply premodern. But for two thousand years, the steppe people also remained state-of-the-art in their military technology: mounted warriors who could traverse great distances and strategically retreat whenever the battle turned against them. With powerful compound bows, they could shoot while mounted, thanks to a lifetime in the saddle.

It was often far easier for settled societies to pay tribute to the people of the steppe than resist their incessant raiding. The East Romans paid tribute to the Huns, and so succeeded in deflecting the attention of these invaders away to the west. Similarly, it was usually far more cost-effective for Chinese emperors to provide “gifts” to their steppe allies rather than engage in resource-sapping wars.

This is the historical precedent into which the Dzungars stepped. Their ferocity meant that they easily established hegemony over the Muslim people of the Tarim basin, whom we today call Uyghurs. These urban Muslims resented rule by capricious Buddhist nomads, and they welcomed liberation by the Manchus.

Dzungar mobility meant they also interfered in the religious politics of Tibet incessantly and at will for decades. The title Dalai Lama was conferred initially by a Mongol ruler in the 16th century. By the end of the 17th century, the Dzungars were manipulating and controlling succession in the Tibetan Buddhist hierarchy. It looked as if Tibet would be absorbed entirely by the Dzungars, just as the cities of the Tarim basin had been.

The Dzungar-Qing Wars

The years between 1687 and 1757 saw a series of conflicts between the Dzungars, and the Qing dynasty. The war came to an end only when Emperor Qianlong, a man even more cultured than his grandfather Kangxi, demanded the liquidation of the Dzungars as a nation.

In response to the recalcitrance of some of his subordinates to carry out the full extent of his dictates, Qianlong ordered the following proclamation be read out:

Show no mercy at all to these rebels. Only the old and weak should be saved. Our previous military campaigns were too lenient. If we act as before, our troops will withdraw, and further trouble will occur. If a rebel is captured and his followers wish to surrender, he must personally come to the garrison, prostrate himself before the commander, and request surrender. If he only sends someone to request submission, it is undoubtedly a trick. Tell Tsengünjav to massacre these crafty Zunghars. Do not believe what they say.

Of 600,000 Dzungars, up to 480,000 may have died. A 19th-century Chinese historian estimated that 30% of the Dzungar households were directly killed by the Qing armies. Another 40-50% died of disease and starvation. The remainder fled to the Russian Empire or took refuge with the Kazakhs.

The closing of the frontier and the rise of the gun

Qing victory over the Dzungar was total. The Dzungar nation lost its ability to resist and rebel. This marked the arrival of the Eurasian heartland into the modern geopolitical system. Before the rise of the Qing and the expansion of Russia into the Eurasian interior, the vast zone had been occupied by mobile nomads and hunters. There were no true borders on the map, there was territory occupied and inhabited. The nomadic response to encroachment was to fight or retreat at the first sign of weakness. They rarely took any significant losses due to their customary strategic depth.

But the partitioning of Central Asia by Imperial China to the east and Imperial Russia to the west closed off all avenues of retreat to the Dzungar. The nomads’ attempt to play Russia off against the Qing met with mixed success at best. The Russians knew a vigorous coalition of nomadic warriors could cause them trouble in the future. They remembered being ruled by Tatar nomads.

With the development and spread of firearms, nomadic advantages in warfare also diminished. Modern states with extensive systems of logistics were more effective in fielding large armies for long periods in distant locales. The Qing wore down the Dzungar, and ultimately the campaign of genocide left Dzungar soldiers no homes to retreat to.

Rationality and the total state

The Qing dynasty ruled a China that was heir to thousands of years of Confucian statecraft. But the Manchus remained a cosmopolitan and imperial people who also operated outside of the boundaries of Chinese thought and precedent. In 1691, they signed the Treaty of Nerchinsk, which established a border with the Russian Empire. Their patronage of Tibetan Buddhism was not in keeping with Chinese tradition, but unsurprising from a people of the eastern steppe and forest, who had shifted from shamanism to the religion of the Tibetan Lamas in the decades after 1500. It also allowed them to absorb and integrate Tibet into the Chinese Empire for the first time in history.

The destruction of the Dzungar Khanate also established the western border of the Manchu Empire in what the Chinese today call Xinjiang, literally “New Border.” Whereas earlier Chinese Empires had been content to watch their influence gradually fade into the steppe and desert to the north and west, the Manchus established clear lines and borders all around the perimeter of their domains. Though distinct from the Westphalian tradition of Europe, the Manchus rationalized the geography of China so that it transitioned easily into the modern era. Today's internationally recognized borders of the People's Republic of China are the outlines ruthlessly carved by the Manchu Empire.

The Manchu victory over the Dzungars was not due to their particular skill or ferocity in the arts of war. Rather, they deployed the whole might of the Chinese nation and various allied peoples (Manchus, Mongols, and Turks) against the Dzungar in a war of attrition. Modern weaponry erased the long-held advantage of the steppe nomad against the Chinese infantry on a man-for-man basis. Science, engineering, and modern politics conquered the steppe and exterminated the Dzungar.

The greatest human stain

The reason European philosophers like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and Voltaire admired China is that it seemed to be a rational empire. Voltaire also envied what he perceived to be the subordination and marginalization of religion in Chinese statecraft, in contrast to the coordination that was typical in Europe at the time.

This was an indigenous development within China, ruled by the Manchus, a non-Chinese people. It was part of a broader arc of economic and political progress across the world, as states rationalized themselves, and scientific and engineering principles unblocked long-standing stalemates. The process bore its full fruit in Europe, which conquered the world. But the example of China in the 18th century illustrates that elements of it were present at the other end of Eurasia.

The Dzungar genocide, and its resemblance to later atrocities under Americans, Turks, and of course Germans, shows that no time, people, or place is any guarantee against inhumane behavior. The Manchus had experienced decades of rebellion and recalcitrance on the part of the Dzungar. Their ultimate solution was to end the Dzungar as a people, thereby unburdening themselves of the long war. This was simple logic.

The Uyghurs have been far less violent and problematic for the People’s Republic of China than the Dzungar Khanate was for Qing China. But the power and totality of the modern state have progressed far beyond the 18th century. The reach and encroachment of the modern surveillance and police states are like nothing Qianlong could imagine. Instead of exhortations to obey, all that is needed today is a decree specifying that authorities should “show absolutely no mercy” to the Uyghur “separatists.” And like that, the mechanism of the modern totalitarian state snaps into motion, a blur of bureaucratic paperwork and punctilious attention to the details of slowly destroying another race of humans.

When we in the West react with incomprehension to the horror unfolding in those remote outposts, we need to realize it is not without precedent. It is not an act of capricious evil, but a calculated decision. Genocide was built into the foundations of Xinjiang itself, the contested soil suffused with the blood of the exterminated Dzungar people. I’m hardly one to exhort anyone to do anything. But ours is an age when earnest Americans announce unbidden whose stolen native lands they occupy as readily as they proclaim their pronouns. So could we just supplement our long-distance concern and hand-wringing with a thought for the actual facts of the western frontierland of China? Xinjiang is Dzungar land emptied of Dzungars. And now it looks poised to be emptied of their Uyghur successors. Sadly, genocide, that darkest of human stains, is not a recent Western invention, but Made In China, too.

A good write up but in the prologue and conclusion you commit the usual western fallacy of equating culture-cide and geno-cide. They aren't the same (though often go hand in hand). This false equality is at the root of western inability to confront barbarian cultures in their midst. After all saying bad things about culture inevitably means genocide.

But the two concepts are distinct. Killing memes is not killing people. If Chinese manage to eradicate Islam from Western Turkestan (or utterly neuter it) - good for them and congratulations. If they manage to do it without killing people who don't fight them - there is no moral problem with what they are doing. If, on the other hand, they kill indiscriminately with the intent to "kill them all" this would be something to object to.

It is hard to tell given the abysmal quality of "reporting" from these areas but it seems that Chinese are doing the former rather than the latter.

I'm afraid the more recent American schoolyard chestnut "he who smelt it, dealt it" better explains the convenient "amnesia" we see in the west.

Just to illustrate the point...take a look at a map of Xinjiang. It happens to be right next to...Afghanistan. The country where for two decades, the locals have been subject to western re-education, airstrikes, torture, and weapons testing (remember the "M.O.A.B."??).

Furthermore...take a look at a map of oil reserves in China. Xinjiang happens to have the biggest "blob of black". Curiously similar big "blobs of black" happen to trapped under regions where the west has "human rights" based regime change policies (Venezuela, Iran, Iraq).

President Trump (who I actually like) says "we're not so innocent - and we're going to take the oil!". It happens right in front of our eyes in Syria...and rather than any discussions about boycotts of American goods & sanctions on their leaders...you get brave academic dissertations about the benefits of stealing Syrian wheat on top the oil!

Having said all this...you don't want "culture-cide" of the Uighur's (sorry Eugene G.!). They're beautiful people, beautiful women, beautiful dresses, beautiful dances. But more importantly, this world needs more "conservative" types with strong family values. Eugene compares them to "barbarians". But when American culture consists of Disney-owned ABC & NFL star Michael Strahan celebrating "Bacha Bazi" on national television...ain't that "backwards"? (ever heard of Sodom and Gomorrah??). Certainly more backwards than anything I've heard the Uighur's accused of!

You ask me (no one does, on account of being a highschool dropout) the key to "saving the Uighur's" is being sincere. You can't have the desire to cripple China in your heart - while spouting hypocritical sanctimony from your mouth. You can't unfairly personalize this issue around Xi Jinping - because you want to protect your future ability to do business in China.

If I (to reiterate, a highschool dropout) can see through it...then of course the Chinese see through it. And that's not helping anyone. We need to have man-to-man relationships, crude jokes, and possibly some innocent misogyny. It's what we used to call "diplomacy" (before those jobs became rewards for friends & funders).

Without getting into specifics (probably because I want one of those "reward" appointments lol!) there are successful eastern examples of "fundamentalist Islamic communities" being integrated into "secular" nation-states. The peoples retain their "hard" culture & identity...yet end up becoming loyal & valuable resources for the state & military. It's the key to "saving the Uighur's" & "preventing a genocide/culturecide"...yet not one western "scholar" has considered or proposed such a solution.