Lost Green Saharans: ancient DNA unearths a new race from a verdant North African interlude

These 7000-year-old humans are neither Eurasian nor sub-Saharan African

Remember how simple our story used to be? Twenty-five years ago, our line was that the fateful lineage leading to us, the anatomically modern populations who dominate the planet today, began with a big bang about 200,000 years ago. A single massive wave like a demographic tsunami rushing concentrically outward swept away all competing branches of humanity, snuffing out their separate flames, mercilessly pruning so many disparate branches from the vast and ancient tree that stretched back over a million years to the roots of our hominin lineage. Today, a generation on, by the light of incessant bombshells of insight from computationally powered modern genomics and the laboratory wizardry of paleogenomics, our simple story is long gone; and every few years seem to produce yet another verified side plot or narrative twist to complicate the story of us. Our terse Hemingway novella insists on becoming a sprawling 19th-century Russian epic, its confoundingly complex plotlines interweaving across continents and epochs.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised. With the relatively small data sets of the late 20th century, it stood to reason that our best models would be simple, too. When raw material is sharply constrained, the edifices produced tend towards minimalism. Today, with the whole genomes of thousands of ancient humans, including from three major lineages, Neanderthals, Denisovans and the African populations that led to all of us, we are no longer constrained by a lack of relevant data. A vast theoretical cathedral is now being erected, no rude preliminary sketch, but a detailed demographic simulacrum of what once was, the dream of eventually working out every detail and nuance more fathomable by the day.

Much of the story to come in the next few decades of human population genetics will unfold in sub-Saharan Africa, as our tools and methods rise to the challenge of illuminating our deeper origins. But though Africa south of the Sahara is the site of most of our species’ evolutionary history, today we’re adjusting to a revelation not out of the cradle of humanity, but from the sands of the continent’s largely barren northern third.

In 2000, the plot was dead simple. A small group of expansionist East African modern humans left the ancestral continent 50,000 years ago, and exterminated all of our cousins, from the Neanderthals in Europe to assorted other hominin populations (these latter at the time unnamed) in East Asia. By 2010, it became clear that the extermination had not been complete; non-Africans carried Neanderthal heritage from an admixture event early in the out-of-Africa migration timeline, likely in West Asia. More surprisingly, we also harbored Denisovan ancestry, traces of an eastern human species that was discovered solely by genomics. And the surprises kept coming. In 2014, geneticists scanning patterns of relatedness across ancient and modern humans realized there had been a branch of non-Africans who never mixed with Neanderthals, and whose heritage many West Asian populations carry. This heritage was also brought to Europe and South Asia during the agricultural revolution’s demographic expansions starting 10,000 years ago. We termed this population “Basal Eurasians,” for their early split from other non-Africans, over 50,000 years ago.

But, like all other non-Africans, Basal Eurasian genes attest that that group too is a product of the “great bottleneck,” a period of thousands of years when the ancestral breeding population of all humans except sub-Saharan Africans collapsed to the scale of just some 1,000 individuals, give or take. It seems likely that Basal Eurasians 50,000 years ago occupied territory in West Asia or Northeast Africa, so they never had a brush with Neanderthals, like their non-Basal cousins, who pushed north and east into the highlands of Iran and the Caucasus. There, our ancestors absorbed a large population of Neanderthals before sweeping outward to the north, northwest and east, taking their Initial Upper Paleolithic (IUP) toolkit all across Eurasia and onward to Australia. The story then, until 2025 ran that the “out of Africa” humans had developed in isolation, and a branch had eventually gone on to conquer the world. This small out-of-Africa population was one of multiple human groups who branched off from Africans south of the Sahara, specifically from East Africans.

Recently, that story has received a significant plot twist. Early modern humanity was a bigger family than we thought. Over 50,000 years ago, the ancestors of today’s humans were divided not just between sub-Saharan Africans and proto-Eurasians, but into at least three broad categories, because now paleogeneticists have uncovered a lost branch of humanity that long occupied northern Africa, separate and distinct from the sub-Saharan populations to their south, and the Eurasians to their east. These were the Ancient North Africans (ANA), and we now have three genomes where this exotic heritage predominates, their 2025 publication opening a new chapter in the quest to retrace the human journey at a level of granularity unimaginable in 2003 when the site was first excavated.

The other Africans

The unwieldy term sub-Saharan African encompasses all the variegated peoples south of the Sahara desert. A simpler label might be black Africans, but populations like the San foragers and Nama pastoralists of southwest Africa have lighter skin than many tropical Asian peoples. An essential aspect that has set sub-Saharan African population structure apart since the emergence of molecular evolution in the 1980’s is that it remains the most genetically diverse on the planet because its peoples alone were spared the great bottleneck that all other known humans endured (or so we thought). This has preserved such wealths of genetic diversity that we find the Khoisan of the far south are genetically more distinct from West Africans than West Africans are from Eurasians (who are, of course, ultimately descendants of East Africans). The cleavages within Africa are deepest and most ancient in the south, but now new light has been shed on the oft neglected north, which in our day is mostly uninhabitable desert.

An April 2nd, 2025 paper in Nature introduces us to an additional population that also skipped the great bottleneck, and also were not sub-Saharan Africans. The paper is Ancient DNA from the Green Sahara reveals ancestral North African lineage. This finding is not a total shock, a 2018 paper reporting seven 15,000-year-old samples from what is today Morocco found only an imperfect fit between them and contemporary populations in the region. Located in Taforalt cave, these individuals’ genomes bore affinities to Near Eastern populations, but gave perplexing signs of genetic variation that didn’t really fit any of our existing models of human evolution or the representative list of populations then in our datasets. The challenge with the Taforalt samples is that it’s hard to understand admixed populations without a good grasp on the putative source populations in the first place. Imagine trying to solve for x in the equation 2 + x = 6 if you know no numbers beyond 2. It just doesn’t compute.

The Nature paper genotypes three individuals from 7,000 years ago in the deep Sahara, in southwest Libya. These new probands were much more geographically and genetically isolated than Taforalt’s Pleistocene Moroccans, and the Libyan genomes offer much more unambiguous evidence of a previously unknown and distinct ancestral population that must have flourished across North Africa for tens of thousands of years prior. The Taforalt individuals were the first clue that our existing understanding of African population history had serious gaps; prehistory north of the Sahara was more complicated than we had thought. Of the three individuals found in the Takarkori rock shelter in the Green Sahara paper, one furnished truly high-quality DNA yielding over 800,000 markers, and reflects 90% descent from a distinct North African ghost lineage that was neither Eurasian nor sub-Saharan African. Named TKK, this individual’s results make clear and indisputable that a lost race of our species once called the Sahara home.

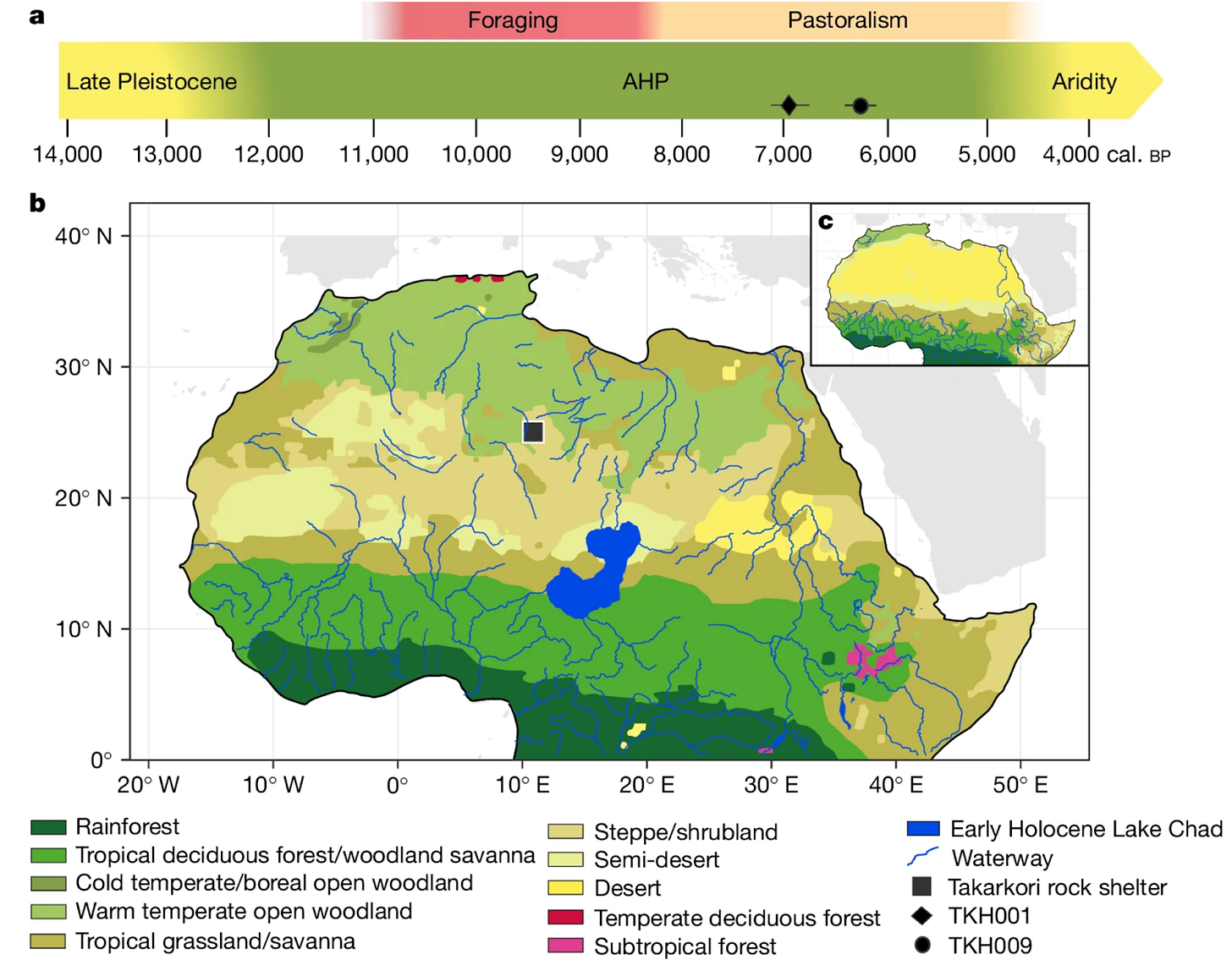

TKK and her lineage flourishing some 7,000 years ago in what is today deep in the heart of the world’s largest desert, are only comprehensible given the Sahara’s climatic fluctuations over the last few hundred thousand years. When TKK lived, the Sahara was not a desert across most of its range. The huge stretch of territory in Africa’s northern third from the Atlantic to the Red Sea was undergoing what is labeled in the paper the “African Humid Period” (AHP), another term for the more colloquial Green Sahara. As is clear in the map above, where inset panel C depicts the arid present and panel B represents the biomes of the wet period, between the end of the Ice Age 11,500 years ago, and 3000 BC, for these crucial millennia, most of the Sahara was not desert. It was instead a mix of woodlands, savanna and scrubland, with only a modest precursor of today’s vast desert along its eastern edge. Humid periods have punctuated the Sahara’s history since it emerged as a climatic and geological entity nearly 10 million years ago. The Eemian interglacial, dating to 110,000 years ago, may have been even more humid than the latest Green Sahara, thereby propelling human populations from the African core northward toward the Mediterranean.