Note: This is the third post in a series. Here is the first post and the second.

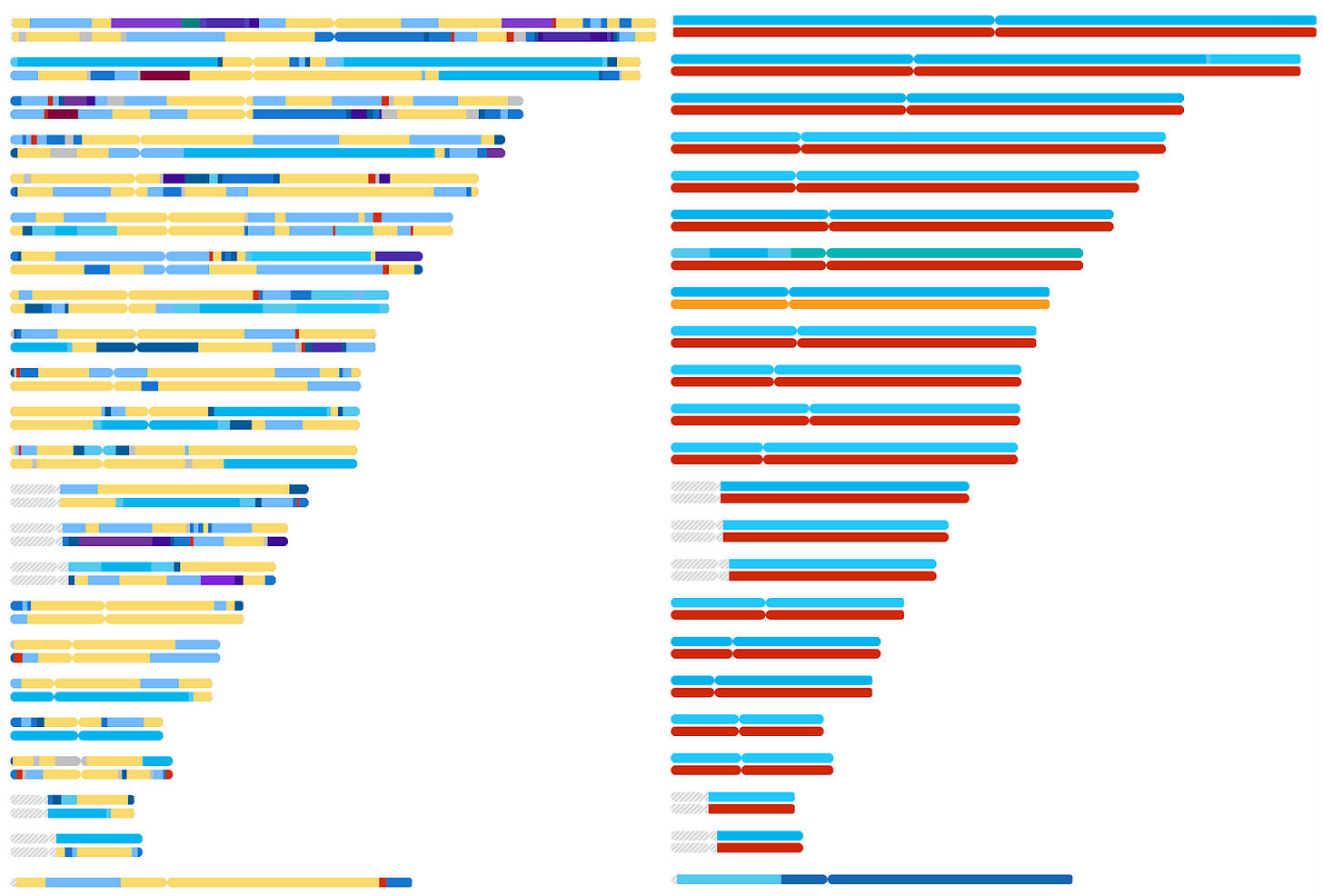

The above plots are of two men who are roughly half European and half East Eurasian (the one on the right precisely so) in ancestry. The individual on the right has a white mother and a Chinese Singaporean father, while the individual on the left descends from a mixed population in Guatemala (to be precise, he is 52% white, 47% indigenous and 1% Sub-Saharan African). Obviously, the East-Eurasian ancestry of the right individual is East Asian Han Chinese, while the East-Eurasian ancestry of the left individual is mostly indigenous American, in his case, Maya. But there are other clear differences between the two individuals beyond their overall ancestral origins. The segments themselves may add up to roughly the same proportions, but their patterns are so different because of the very different histories that these two people embody.

The individual on the right is a first-generation Eurasian, a “filial 1” or F1. The individual on the left is what in the Latin America of his birth is called a mestizo, for his mixed-race background (the term is from Latin mixticius, or “mixed”). The two men’s genomes differ so much despite both being mixed race and in nearly identical proportions, because the timing of their two admixtures is very different. For the F1 individual, no generations of recombination to break apart the long uninterrupted segments of exclusively European and Asian ancestry have yet intervened. In contrast, the Guatemalan individual’s finely minced segments of ancestry are the product of generation after generation of intermarriage between people all of mixed heritage, so that the segments inherited from his European and indigenous ancestors are now thoroughly shuffled along the same chromosomes.

Recombination’s power to reshuffle ancestral contributions is also evident when we look at someone who has one F1 parent and one parent who matches either of the other grandparents’ races, what my plant-breeding colleagues would call a back-cross. The below chromosome composition is someone whose mother is a first-generation Eurasian (her mother Japanese, her father European American), and whose own father is also European American.

Ancestries painted

The total ancestry is about ~25% Japanese, but that heritage is distributed unevenly across the genome. You can see alternating segments of East-Asian and European ancestry on one chromosome alongside uniform European ancestry on its counterpart (Notably, the many instances where 23andMe has phased her Japanese segments onto both copies of the same chromosome are phasing errors. Had either of her parents also been sequenced, the algorithm would have been equipped to phase correctly). The process of meiosis through which haploid sex cells (eggs and sperm) are created also entails recombination events between each contributing parent’s own two copies of each chromosome. Before the pictured individual’s Eurasian mother’s own birth, the purely European and purely East Asian chromosomes you see in an F1’s chromosome painting, had already been reshuffled in the eggs she would eventually draw on during her reproductive life. Thus her daughter inherited the maternal complement of her chromosomes all with long segments alternating between European and Japanese ancestry from her grandparents.

The Guatemalan’s more complex interleaved pattern is indicative of a long history of admixture, because generations of recombination compound, producing variable segments of ancestry with ever shorter average lengths. Just as the distribution of average total genetic variation can be used to reconstruct population history (with smaller subpopulations that cleave off of larger diverse ones being more homogeneous by definition), so the distribution of an individual’s average ancestry segment length can be used to reconstruct admixture history.

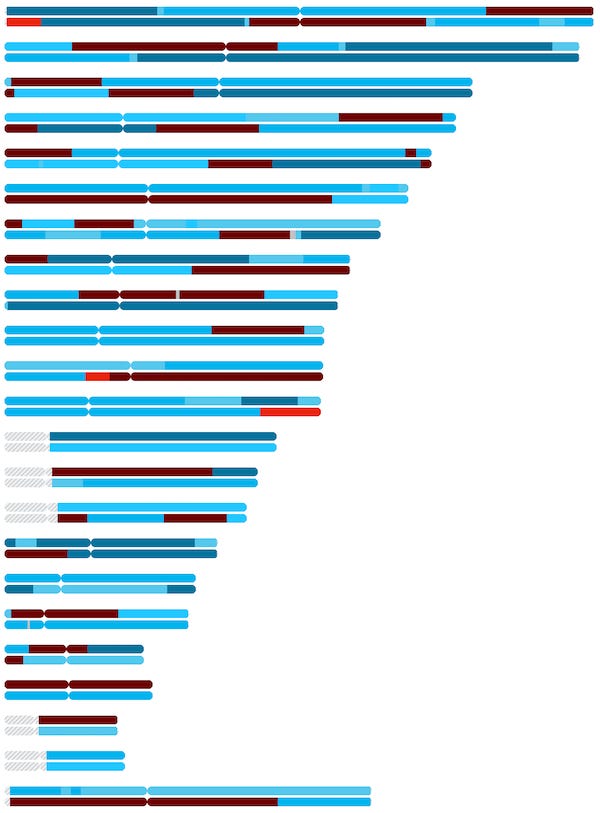

Below is the “ancestry time” from 23andMe for my son.