Life (science) comes at you fast, part 2

It was there all along - learning to read the history written in our genomes

Note: This is the second post in a series. Here is the first post and the third.

The draft human genome was completed in the year 2000 (and yes, technically the complete genome was only finished in 2021), and during the aughts genomics accelerated its deployment of powerful new tools to tackle the field’s long-standing questions. L. L. Cavalli-Sforza published The History and Geography of Human Genes in 1994 as the capstone of a long and storied career. In it he marshaled his (at the time) enormous sample size of 1,800 individuals drawn from dozens of populations across the planet, each of them typed at 110 markers. But many of the open questions posed and explored in that book were actually promptly resolved in the first decade of the 21st century when the power to test the propositions mushroomed overnight. Cavalli-Sforza’s swan song would be the last great work of human population genetics utilizing solely classical methods and markers. The Human Genome Project was ushering in a new era, as computers and massive sequencing machines became as central to the geneticist’s toolkit as the pipette and agarose gel.

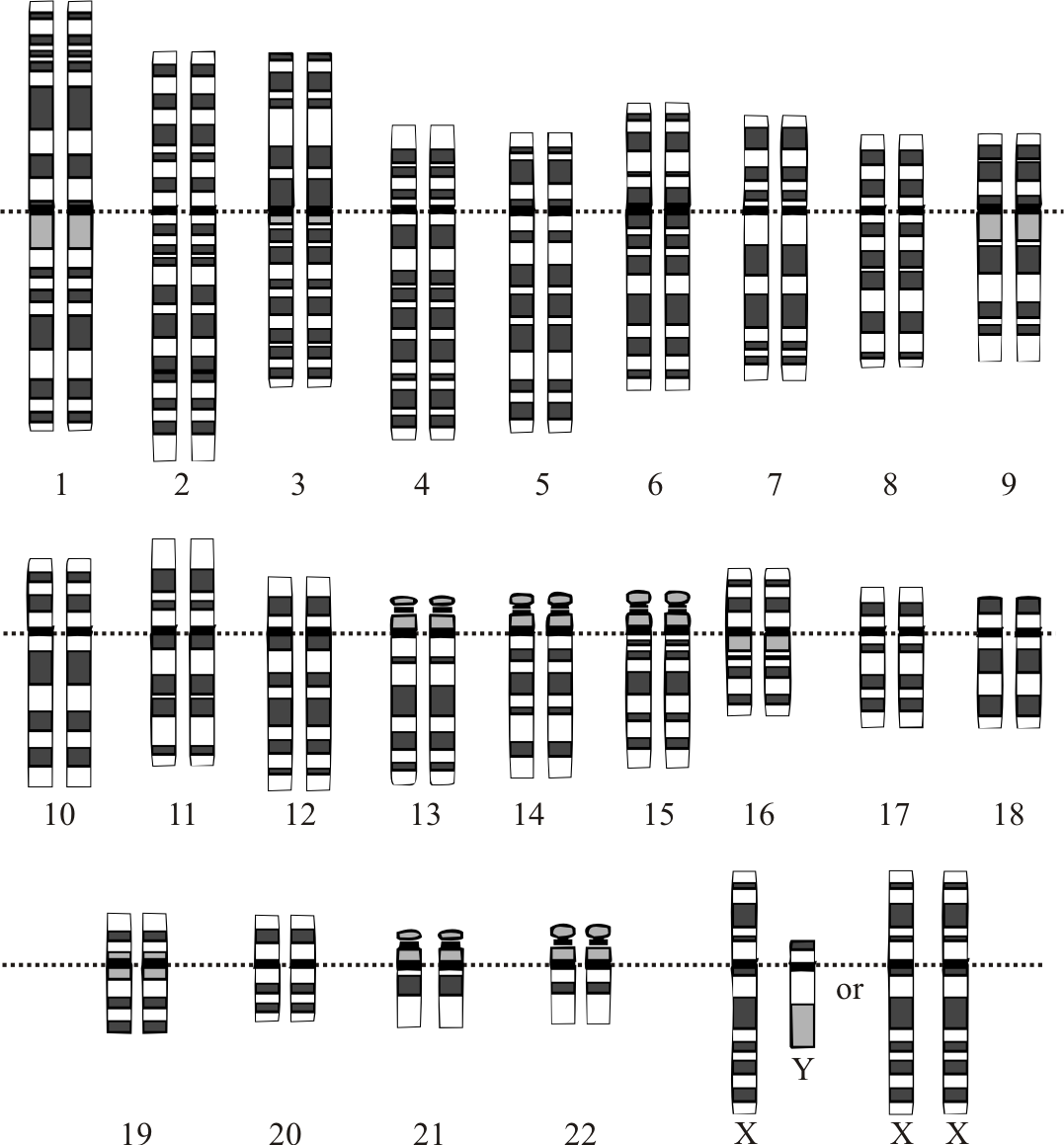

In 2008, the next generation of scientists at Stanford took 938 unrelated individuals from 51 populations of the Human Genome Diversity Panel (mostly, in fact, from Cavalli-Sforza’s 1,800 sampled individuals), and using chip technology genotyped each at 650,000 common, highly informative (because of their high variability) base-pairs, or SNPs (for single-nucleotide polymorphisms). A good example to illustrate the concept and utility of SNPs is the variable position rs1426654 within the gene SLCL24A5, where the genotype GG correlates with darker skin, and AG or AA with lighter. The frequency of the A allele is nearly 100% in Europeans, while G is nearly 100% in East Asians and Africans. Other groups, like South Asians, have a mix of A and G, explaining much of their variation in skin color. Often, SNPs vary within families. As it happens, I’m AA on rs1426654 just like my wife, but we differ, for example, on the SNP for sensitivity to bitter tastes within TAS2R38. I’m CC, meaning I cannot taste some flavors of bitterness while she is CG, and therefore can. Our children are a mix. Though I only have the C allele to offer, my wife contributed the G allele to one of our kids, so the two of them both can taste many bitter flavors the rest of us can’t detect.

Though the Stanford researchers only genotyped half as many individuals as Cavalli-Sforza had fifteen years earlier, their 6000-fold increase in genomic information per individual (recall that the state of the art passed from a yield of 110 genetic loci to 650,000 SNPs in less than two decades) yielded a deeply insightful and widely cited publication in Science. The bombshell paper came complete with crisp plots (see the beautiful barplot below) and phylogenetic trees of human population structure, and exploded across the media and scientific literature as if it were divine revelation. We stood amazed. It was that unexpected that we could actually know and visualize these deep insights.