Life (science) comes at you fast, part 1

Genetics is dead, long live genomics

Note: This is the first post in a series. Paid subscribers can access the second and the third.

It is a statistical truth universally acknowledged that a lone sample, the proverbial anecdote, is vastly inferior to a large, plural sample, the proverbial data. After all, one random sample might well be wildly misleading. And as any scold will be happy to tell you, the plural of anecdote is not data. I am definitely among those guilty of having muttered snidely, “and what was the N?” upon hearing some implausible “finding” trumpeted by a credulous newsreader.

And yet… in my own field of human population genetics, a curious reality has been verified over the past twenty years of tandem great leaps forward in computing power and genomic data generation. Far from being a nearly useless anecdote, one single human being’s genome is actually an incredibly, almost incomprehensibly informative and faithful window onto millennia of our species’ population history. And I don’t mean some carefully chosen human, a lucky repository of extra-informative genes, poised just so on some key cusp of change amid ceaseless successive generations of human history. I mean any human. Pick a genome, any genome, peer inside the whole genome sequence (WGS), and behold chapter upon chapter of human population history unfurl.

Why? The simplest reason is that we contain multitudes. Coiled in the nucleus of every cell in your body is an indelible record of the personal travel history, the love affairs and the shameful secrets of thousands of those ceaseless generations of your ancestors. If you were raised in your biological family, those nearest generations of ancestors whose tales your DNA tells in the most copious detail, come with faces you can see in your mind’s eye, laughs you would recognize anywhere, a telltale gait common to their sibling cohort. But a WGS allows you to continue climbing past those sturdiest, lowest branches that bear a distinct family resemblance. Every successive generation further up into the canopy branches wider and consists of progressively more slender, gossamer traces of your distant, ever less familiar forebears. And at each higher story in the canopy, those individual branching tendrils that contribute ever-smaller threads of your unique DNA are shared with more and more of your fellow humans. The higher you climb, the more long-ago humans your DNA samples, until after an accumulation of generations, your genes simply offer a faithful record of one large tranche of human population history, the gnarled bramble of interrelationships eloquently reflecting the long subplots of your race, your continent and your species.

The most powerful reason a lone human’s genome can now confirm such a staggering amount of human population history isn’t really anything unique to humans at all. It is the simple application of a richly elaborated toolkit of methods and inferences tested and honed over the century of statistical genetics’ history. These powerful, empirically derived observations and assumptions might have been gleaned at a time when they could be tested on all of say, four markers per sample, but they apply with equal fidelity to today’s millions of markers. And they undergird every insight we reap today with our astonishingly god-like new computational power and serendipitous leaps forward in DNA extraction and amplification. They are common to all life. But for a child of the 1980’s like me whose boyhood reading in history and prehistory was littered with seemingly eternal debates and open questions, ours is an absolutely revelatory golden age of illuminating addenda. Every year brings more decisive and usually incontrovertible evidence about ancient people’s once uncertain movements, mating choices, murders and conquests.

But why does each individual human genome offer so much information? Surely it is only the slow accumulation of so many WGS results from humans on every continent that delivers these insights? Actually, no. Already in 2000, with the very first sequence of a human, a composite of five individuals, including geneticist Craig Venter, we began to harvest these previously unverifiable high-fidelity details of our human past.

Each early genome relevant to a specific story of human population history can be thought of as a rough draft. Successive samplings of similar humans tend only to refine, tighten and fill out the plot details. The overall thrust of the story is already in place from the first writing. This continues to prove true whether the genomes in question are thousands of years old or literally collected by someone last month spitting into a plastic vial. In 2009, I shared the 650,000 markers of my genome-wide 23andMe data publicly and was happy to hear from multiple people studying Indian population genetics that they found my ancestry composition, South Asian but with a substantial East-Asian component, informative of how Bengalis were distinct from Indian populations to their west. And in fact, later more formal studies of larger numbers of Bengalis would reach the same conclusion. The genetic truth will out, even from a first draft.

Genomics eats biology

The first draft of the human genome was completed at a cost (in today’s dollars) of about $3 billion. Just 22 years later, any consumer can buy a kit from Nebula in the US or Dante in Europe, and send in their spit for a whole-genome sequence at a cost of between $100 and $1,000 dollars.

Like it or not, the genomic revolution is here. In the next decade, it will worm its way into your healthcare, while it is already transforming fields like forensic science. And yet, cherished biomedical advances anticipated by the first sequence over twenty years ago remain futuristic dreams. In his speech announcing the completion of the draft genome, President Bill Clinton boldly predicted that in the “coming years, doctors increasingly will be able to cure diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, diabetes and cancer by attacking their genetic roots…it is now conceivable that our children's children will know the term cancer only as a constellation of stars.” We haven’t cured these diseases yet (though CRISPR genetic engineering technology will probably take a big bite out of some of them in the next decade). And alas Clinton’s grandchildren probably will know the term cancer for the disease since they will become teenagers in the 2020s with no cure in sight.

A single composite human genome did not transform medicine or usher in an age of miracles. That promise still awaits. But a different story, in a different field actually more than deserves the hype and hyperbole of Clinton’s long-ago speech. In the twenty-odd years since that first draft whole-genome, genomics, as applied to human history and prehistory, has actually quietly recorded one of the most audacious leaps forward in the history of human knowledge. In human evolutionary biology, literally a genome here, and a genome there, has completely exploded the scope of possibility, illuminating with startling clarity countless uncharted landscapes from our past. We may not see a cancer-free future in our lifetimes, but we now know the past with incredible perspicacity through the data and tools provided by 21st-century genomics.

And perhaps most extraordinary, again and again, we have seen that all it takes is one genome. A single genome from a San Bushman in 2008 allowed scientists to conclude that his was indeed an incredibly genetically diverse population, the most internally diverse of all extant human populations. Two years later, a single genome from Denisova cave allowed scientists to add a whole new species to the human family tree. And in 2018, a single genome, (and this time admittedly, an incredibly lucky find) again from Denisova cave dating to a period 90,000 years ago, was enough to verify the specific existence of a girl whose mother was pure Neanderthal, and whose father was a Denisovan (and that he himself already had distant Neanderthal ancestry).

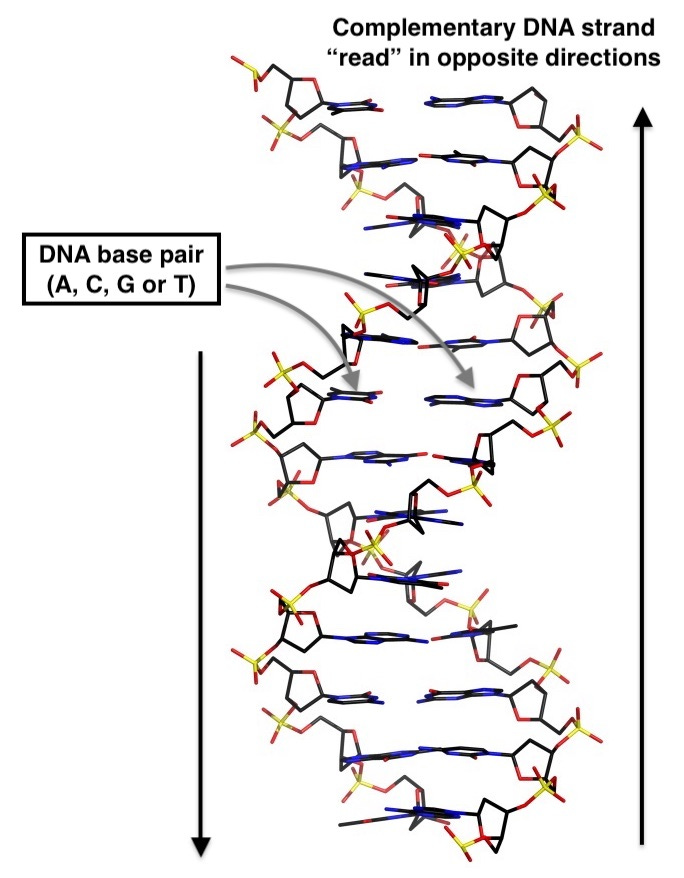

But how can researchers possibly draw such sweeping conclusions about whole populations from a single human genome? Isn’t one human’s DNA just… one data point? First, let’s get a little technical about what we’re now working with. We have to recall that a sequence of DNA consists of three billion nucleotide bases, A, C, G and T, arrayed as complementary twin strands. Taken as a whole, the dual copies of those three billion base pairs (base pairs meaning simply single points in the genome where each parent contributes one nucleotide base: A, C, G or T) is what we now most often mean when we say “genotype” (although confusingly, not so long ago in the pre-genomic era when reading three billion bases was unfathomable, the term actually just connoted genetic variation at a single genetic location).

Moving up in structural complexity, the genome can be further organized into 19,000 genes embedded in vast swaths of “junk DNA.” This surfeit of information within a single genome means that one human sequence can recapitulate our species’ history. The patterns within the genome are the outcome of every individual’s evolutionary past. Discern those patterns, and you bring the past vividly to life. So far so good, but how?

Population history from a single genome

When L. L. Cavalli-Sforza published his magnum opus, The History and Geography of Human Genes in 1994, his data set held 1,800 individuals whose genetic variation was sampled across 110 markers per person. Contrast this with the millions of meaningful markers you can delve into from your own genome, one by one, on your laptop next month if you send in a direct-to-consumer personal genomics kit today. Cavalli-Sforza published after decades of intrepid sample collection and curation, but he had the misfortune to be just a crucial handful of years too early. The exponential growth rate in information technology that Ray Kurzweil discusses in The Singularity is Near took off in population genomics after the year 2000. Even just over a decade later, the myriad secrets held in his samples from around the planet could have been laid bare to his team on a base pair-by-base pair basis . The power we already take for granted today represented such an unfathomable leap forward, geneticists working in Cavalli-Sforza’s Stanford lab in the 1990’s have since told me they literally didn’t see the revolution coming; it was such an immense, tedious struggle just to assemble 110 markers per sample, geneticists working at the time sincerely doubted we would ever innovate the technology to whole-genome-sequence human DNA. Life (science) comes at you fast.

When the revolution suddenly came, it was a perfect storm of simultaneous revolutions in computing and automation, as well as iterative improvements in bench biology. In the 1990s, the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method enabled the amplification of trivial source amounts of DNA, crashing the lower limit of sample material required for the extraction of genetic information. The same decade also saw the beginning of a wholesale switch from researchers laboriously visually identifying genetic variation by inspecting individual bands on gels to the computational assembly and alignment of massive volumes of automatically machine-generated DNA fragments. By transforming genetics into a robotically driven data-generation project, the power of Moore’s law was brought to bear on biology, as incredibly powerful computers and parallel processing relentlessly chipped away at the cost of information extraction.

Advances like Illumina dye-sequencing in the aughts and nanopore sequencing in the teens also improved the fidelity of data that progressively more powerful computational algorithms could then reassemble into a finished whole genome sequence. At the same time, the less ambitious but still highly informative techniques of genotyping key subsets of the genome that exhibit extreme variability took their own leaps forward. In less than a decade after the Human Genome Project, technologies utilizing genotyping chips to probe specific fragments from key sites went from returning hundreds of markers to a million.

From an explanation point of view for general reader for why a single genome tells so much, I think you missed hammering on the most common baggage a general reader brings to the table. The general reader thinks we know what genes do. So hammering on this NOT being true is critical. I think most readers will still miss this point after reading your post (FWIW). The key insight is genomic ancestry techniques (for the most part) treat the functionality of genes as unknown and not even needed. So what's required is to have a set of baseline genomic guideposts to compare new finds against. That set of guidepost/baseline genomes is what makes a single genome so informative. If we only had a bare bones single Denosivian genome but no baseline to compare it to, it would tell us nothing.

Anyway, enjoying the series as always. And just my two cents of reaction to reading this particular post. If you think there might be something to it, perhaps you can ask readers you know who aren't aware of this, and see if they missed this point or not. And it could help determine what to cover in future.

Great article. And the third paragraph of the opening is one of the most inspired, beautiful paragraphs I've read in a long time -- not the least because it so wonderfully captures what has so fascinated me about this subject since I first sent my sample to the Genographic Project many years ago, and then watched in amazement as the golden age of genetic discovery blossomed. What a ride!