Land acknowledgement, Greenland edition

A saga of human survival gives “indigenous,” “native,” “homeland” new meaning

In large precincts of left-leaning America, it has lately become commonplace for any official proceeding to be delayed until someone has intoned a somber statement of guilt acknowledging the locale’s legacy of colonization, its history as another people’s ancestral homelands (sometimes with such specificity as “since time immemorial”) and with homilies to such things as the “inherent sovereignty of indigenous people” who previously resided there. Such a self-serious ceremony could scarcely flourish (nor be so succinct and straightforward) anywhere but a continent with as few layers of human churn and conquest as North America.

But setting aside the specific bloody legacy of America’s European conquest and lingering questions of guilt and responsibility, it’s worth considering what a quarter century of genome-powered population genomics can now tell us about our upstart species’ general tendencies to usurp and wholly replace prior inhabitants. Is North America somehow unique? What do we know today about human patterns of replacement that we could not determine centuries ago when an informed person might have actually believed indigenous Native Americans had been in their “ancestral homelands” since time immemorial, rather than for some 15,000 years?

And what does it really mean to be indigenous, to be native, now that we can genuinely interrogate the layers of our species’ population history? What if a people whose genetic close kin we are accustomed to regarding as marginal or indigenous (with all the respect, compassion and pity that tend to so swiftly attach themselves to such designations) are the usurpers? What if they arrive last and are the last men standing? What if it is they who out-compete and supplant a locale’s entire contingent of long-time inhabitants? What if those vanished early inhabitants are Europeans? And what if when the dust settles, we see that the commonality of these johnny-come-latelies who out-compete long-time inhabitants and master a new locale, is not race, continent of origin or bellicosity, but simply an upgraded toolkit that runs circles around that of the locals’?

This is the case for Greenland, our subject today. We apply a genomic lens to the millennial saga of humanity’s quest to master one of the planet’s most unforgiving pieces of terrain. And if the non-European champions of our tale, the ancestors of Greenland’s 50,000 inhabitants today, supplanted both Norse and Dorset forerunners, is it time they draft a land acknowledgement? Or shall we defy chronology and regard them approvingly as native Greenlanders “since time immemorial”? Perhaps neither. Perhaps we can simply recognize that their story and their land’s long saga is proving to be among the most commonplace of human population plotlines.

* * * * *

In 1408, Thorsteinn Ólafsson and Sigríður Björnsdóttir, were joined as man and wife at Hvalsey Church, in modern-day Qaqortoq on the southern tip of Greenland. The bride and groom both had Icelandic origins, and we know of the wedding because of its mention in a surviving Icelandic letter dated 1409. Though their union at Hvalsey Church suggests they might have planned to make a life together in Greenland, settling down among the Norwegian-descended settlers who had by then retained a foothold along the great island’s fringes for over four centuries, the couple departed in 1410, returning to their native Iceland. Their nuptials mark the last written record of Europeans in Greenland before the modern era, though archaeological evidence suggests that presence persisted for several further decades before the ultimate extinction of the medieval Greenlandic Norse civilization.

The Hvalsey Church wedding was one of the final acts in the annals of a European outpost already old by the 15th century. In 982 AD, over four centuries prior, Icelanders exiled the landowner Erik the Red from their homeland for murdering his neighbor (Erik’s own father had fled Norway over a murder as well, bringing his wife and 10-year-old son to Iceland). Erik was prosperous, an important figure on the small island. He had followers who stood with him and were ready to follow him into exile. The small party ventured into the cold, rough seas of the North Atlantic with a boldness characteristic of the period’s pagan Norse. It was 180 miles beyond Iceland that he and his small party made landfall. There, they discovered the imposing landmass Erik would name Greenland. The world’s largest island, fully 30% the area of Australia, looms famously oversized on Mercator projections. But even scaled more accurately, Greenland remains three times the size of Texas. This vast near-continent is mostly a world of ice, over 80% of its surface covered by a permanent glacier that holds nearly 10% of the planet’s fresh water.

Erik the Red seems to have given Greenland its rather optimistic name as a marketing ploy, apparently presuming presciently that the name would better entice others to join him on a return voyage. In 985, his exile ended and he returned home. In short order, he had persuaded two dozen ships’-worth of his countrymen to join him sailing back into the untouched west. After 986, two primary European settlements were established in Greenland. These were blandly christened Eastern Settlement, Eystribyggð (site of Hvalsey Church) and Vestribyggð, for a smaller Western Settlement (which actually lies both to the north and west of Eystribyggð). In the generation after the initial colonization, Erik the Red’s son Leif brought Christianity to Greenland, having converted to the new religion at the court of the Norwegian king, Olaf Tryggvason. Lief converted his mother (though not his father), enlisting her to help build the first church in Greenland, easing Greenlanders’ integration into Latin Christendom, and eventually more formally into the kingdom of Norway. In 1124, Eystribyggð received its first resident bishop, a Norwegian named Arnald. A successor, Jón Árnason, appointed in 1189, would make a pilgrimage to Rome and meet Pope Innocent III in 1202 before returning to Greenland, illustrating just how integrated the Arctic Norse became with their cultural cousins in Europe, their island settlements marking the westernmost colonies of Christendom. But just as Europe was stretching itself west across the Atlantic, and establishing a beachhead approaching North America’s northeastern fringe, the New World was marching eastward, as it had for millennia. Greenland was not virgin territory when Europeans arrived; the Norse were actually newcomers in a land haunted by the remains of earlier peoples who had not been extirpated by fellow humans, but repulsed by the harshness of the unforgiving terrain itself.

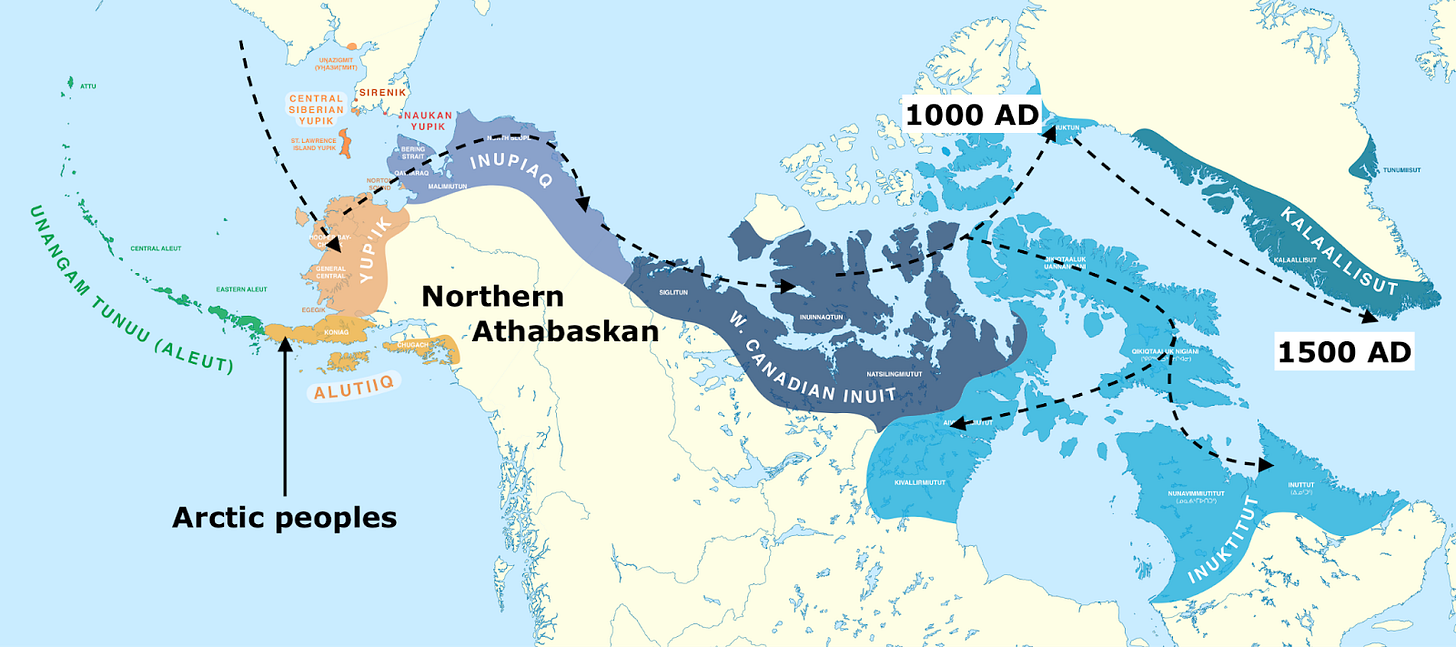

Humans have occupied Greenland since at least as early as 2500 BC. But those earliest inhabitants did not venture across the Atlantic from Europe; they slipped east along the Arctic’s shores, following the north’s copious marine resources, including pods of seals, tempting targets for those foraging across an otherwise desolate landscape. Archaeology labels these polar societies “Paleo-Eskimo,” with the Saqqaq culture being the earliest. Part of the “small tools tradition,” they seem to have begun their migration eastward from a home base in eastern Siberia and western Alaska 5,000 years ago, until they reached the continent’s end in Greenland. As a world on the margins, Greenland’s population numbers have waxed and waned several times over. Norse timing was fortuitous; they arrived in Greenland at the beginning of the Medieval Climate Optimum, a period of warmer temperatures across the northern Atlantic begun in 950 AD, some seven centuries after the extinction of the last Paleo-Eskimo cultures on the island’s southern shores. However, the Norse had neighbors. Called Skræling in the Norse sagas, these were the Dorsets, and their existence beyond the limits of Christian civilization, in northern Greenland and the islands to the west, rendered them a shadowy menace to the medieval Greenlanders. But in a twist, neither of these two peoples, the Norse or the Dorset who inhabited Greenland in 1000 AD, would leave any lasting legacy. Modern Greenland was ultimately to be the easternmost outpost of the emerging Thule culture, which was sweeping across the northern Arctic by boat from a homeland in Alaska just as the Norse were tentatively exploring the North Atlantic. These whale hunters, in contrast to the agricultural Norse, flourished in Greenland’s colder temperatures after 1400, and it was they who would come to dominate the polar world of the north down to the present day.

The First Ancient Genome

Though the Paleo-Eskimos remain an obscure people outside the halls of Arctic archaeology, they represent something of a historical milestone for paleogeneticists, arguably present for the birth of that field as a branch of genomics, rather than just genetics. On February 10th, 2010, Ancient human genome sequence of an extinct Palaeo-Eskimo, appeared in Nature. This was the first ancient human genome to be fully sequenced, pipping the publication of the Neanderthal draft genome to the post by four months, and ushering in a decade-long competition between Eske Willerslev and David Reich, paleogenomics’ two dominant figures after Svante Pääbo transitioned to a more remote elder statesman status after 2010. But timing aside, the Willerslev group’s Nature publication remains notable just on scientific grounds, because with hindsight we can see that it anticipated a later key pattern gleaned from ancient DNA again and again: modern humans tend to replace each other with incredible regularity.

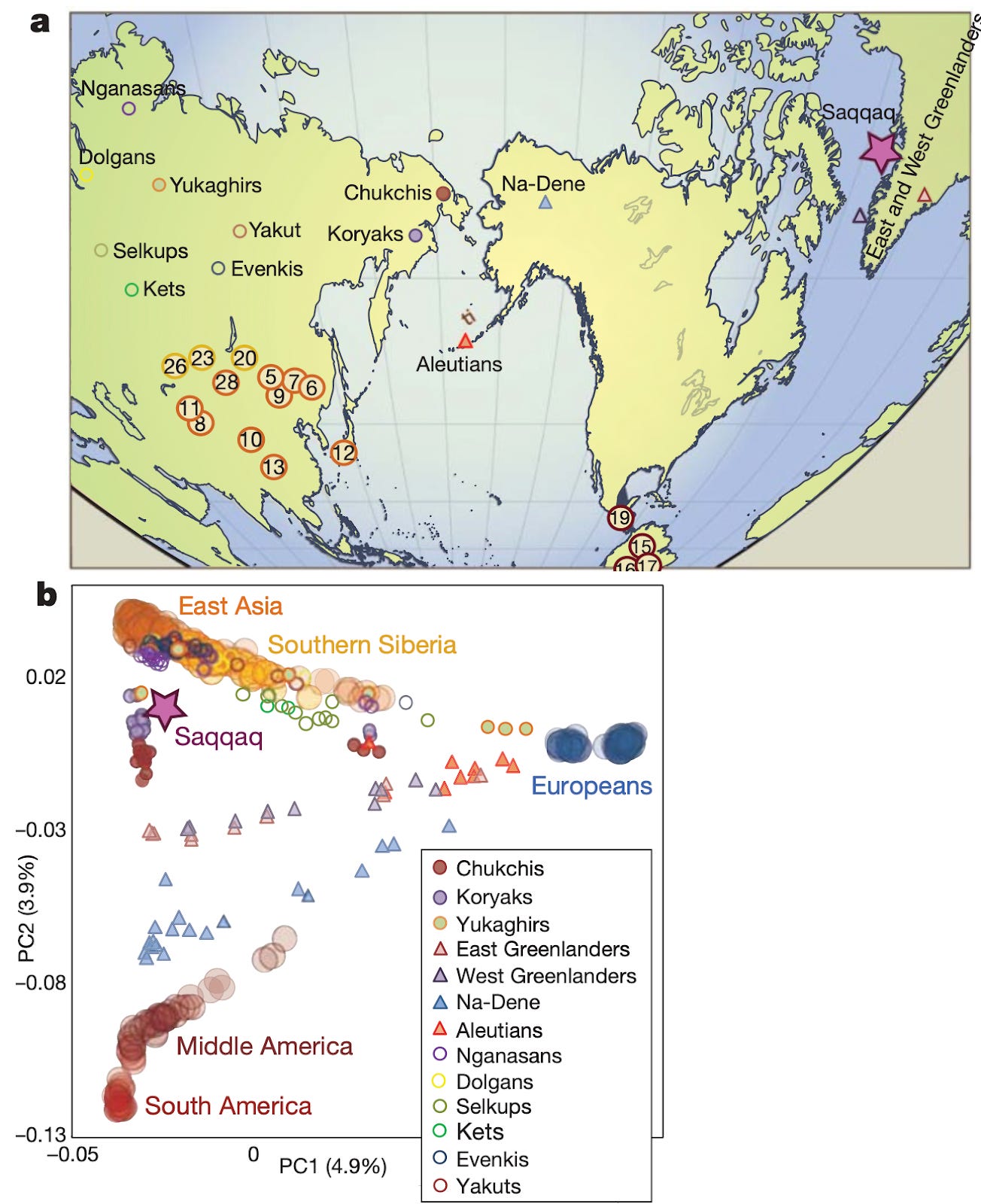

The sequenced individual was a member of the Saqqaq culture, one of the first Paleo-Eskimo societies in the Arctic and Greenland. He died 4,000 years ago, and his people buried him on an island off Greenland’s west coast. The most notable aspect of the Saqqaq genome at the time it was first analyzed is that the individual was not ancestral to modern Greenlanders; indeed genetically his closest matches in contemporary populations live on the far northeastern edge of Siberia, among the Chukchi and Koryak minorities, who occupy territories just across from Alaska in Russian Siberia. What paleogenomics has shown since the Saqqaq paper is that demographic prehistory often delivers such twists and lays bare unexpected distant connections; the genetic discontinuity that made waves in 2010 would surprise less today.

The Saqqaq, and their Dorset descendants are both genetically entirely unconnected to the Amerindians of North America to their south, and, surprisingly also to the Thule culture that would eventually supersede them across the American Arctic, giving rise to present-day Inuit societies from Alaska to Greenland. Additionally, the admixture plot above illustrates a Saqqaq affinity to the Nganasans, the Samoyedic tribe who occupy north-central Siberia’s Tamyr peninsula, just on the other side of the Urals from Europe’s northeastern corner. Importantly, the Nganasans’ Uralic language connects them to the west, to the Finnic peoples whose range eventually expanded to include the eastern Baltic. The Paleo-Eskimo and Uralic connection highlights the reality of a fully circumpolar world whose extent we are only just beginning to fathom via archaeology and genetics.

The Saqqaq genome’s sequencing also occurred at a critical juncture in our understanding of American prehistory. A generation ago, archaeologists knew the Clovis culture from Siberia had settled the Americas in a single pulse some 13,000 years ago. This common origin explained the general physical and genetic similarities of modern indigenous people across North and South America, from the Canadian north to Patagonia in the south, along with the massive megafaunal extinctions that swept the two continents just before the end of the last Ice Age 12,000 years ago. But excessively brittle regnant orthodoxies have a particular way of collapsing; first they weaken slowly, before imploding all at once; today, our understanding is in a state of flux and revision. Evidence from archaeology now makes nearly irrefutable that the New World saw many settlements long before the Clovis expansion, starting before the Last Glacial Maximum, over 20,000 years ago at White Sands in New Mexico and Chiquihuite Cave in Mexico. And though the overwhelming majority of the ancestry of American peoples derives from a single wave of foragers who pushed in about 15,000 years ago from the lost subcontinent of Beringia that spanned the seas between Alaska and Siberia, sophisticated modern genomic methods have discovered telltale but still poorly understood connections between South Americans and the peoples of Melanesia and Australia. The first-pass genetic analyses did discern this in broad strokes, but important details remain to be teased out of the DNA upon much more meticulous inspection. Nevertheless, the genetic methodologies before 2010 did correctly arrive at the truth that the Beringian wave nearly erased earlier genetic signatures south of the Arctic. By and large the earlier peoples left their artifacts, not their genes.

But what was true south of the Arctic, with a single great Amerindian diaspora entirely cut off from its Eurasian roots at the end of the last Ice Age, and then diversifying from initial shared heritage, is much less assured in the far north. To early 20th-century ethnographers working with the toolkit of cultural and physical anthropology’s descriptive tools, the Inuit people dominant in the Arctic seemed both quite physically and culturally distinct from the native peoples to their south. Together with the Aleuts of southwest Alaska, these Arctic peoples speak the related Eskaleut languages, tongues that differ greatly from the Na-Dene languages of North America’s northwestern quadrant. Save for its southeastern panhandle, the modern American state of Alaska illustrates the social and cultural differences between the Arctic and traditional Native America; the two groups of Inuit peoples, the Yupik and Inupiat, dominate the coastal zones, focusing on marine resources, while the Athabaskan-speaking tribes occupy the interior, hunting terrestrial big game like moose, the northernmost extension of North American foraging culture. The Yupik are also unique among American peoples in that they seem to have expanded into Asia as well: several thousand Siberian Yupik inhabit Russia’s far eastern Chukchi peninsula. Unlike the Yupik, who mostly reside in southwest Alaska, the Inupiaq Inuit of northern Alaska are part of an extensive related cultural zone that stretches out toward Greenland, where the Kalaallit branch are today known as “native” Greenlanders. But this wide ethnolinguistic distribution is a relatively new configuration, as the Saqqaq genome’s stark differences from modern Greenlanders underscore.