Korean identity: a story of genetic continuity 1,400 years in the making

One enduring nation out of many

The Korean Peninsula is a geographic nexus point. At its narrowest, the peninsula is just 144 miles across. Surrounded by the Yellow and East Seas on three sides, it descends delicately in organic irregularity from the Asian mainland’s easternmost reaches like a healthy lobe of ginger. To its west, across the Yellow Sea, begins the vast landmass of China's core provinces and to its east are the many islands of Japan. But just as importantly, to the north is Korea’s sole land connection with the rest of Asia, the vast mixed territory of forests, lakes and grasslands that is Manchuria. Following the Manchu conquests of China in the 17th century, the tables turned and successive waves of Han Chinese settlers transformed Manchuria into a northeastern appendage of China. The fallen Chinese, a subject race, conquered their Manchu overlords and the Manchu homeland through sheer force of numbers; ancient Manchuria faded into the annals of history in the era when the American republic was just emerging, going from a land of a hundred tribes to just another Chinese province.

But Manchuria’s unrecorded history holds many of the keys to Korea’s past. Today, the Yalu river sharply delimits the boundary between the communist People's Republic of China and the communist Democratic Republic of Korea. However, where Korea began and Manchuria ended has traditionally been more vague; Koreans and Manchurians have mixed and migrated across each other's lands since before the end of the last Ice Age. The makeup of Koreans, both today and historically, according to ancient DNA, suggest these interactions were a dynamic two-way engagement. Korea’s occupation of a unique central geographic position in Northeast Asia, and the nation’s track record of existential battles for supremacy and survival made the peninsula a merciless, competitive arena. Over the last few millennia, Korea has proven a demographic cul-de-sac where the winner takes all and it’s either up or out, but with “out” generally having all the finality of a Roman gladiator’s first loss, a culling field from the Yalu in the north to Straits of Tsushima in the south. Many people entered, but only Koreans were left standing in the end.

The outcome of this roiling history is a Korean identity and underlying genetics that exhibit a stability and continuity rarely seen elsewhere on the planet. But only by examining the macro-regional history that extends far beyond Korea can we reconstruct the peninsula's past. We must look north to Manchuria, a land until recently of illiterate tribes. And west to ancient China, with its vaunted history going back over three millennia. And finally, we must look east to Japan, a nation with an inextricable connection to Korea, but which pointedly insists upon its separate uniqueness. Two hundred miles east across the Korea strait, Japan appears to be the repeat forward destination for the genetic imprint of prehistoric Korean migrants. This reality is the outcome of the Korean peninsula’s role as both a sieve and a demographic escape valve for the Japanese archipelago. Korea, then, is perhaps an extreme case of geography guiding and straitjacketing history in a nation-state I have yet examined here.

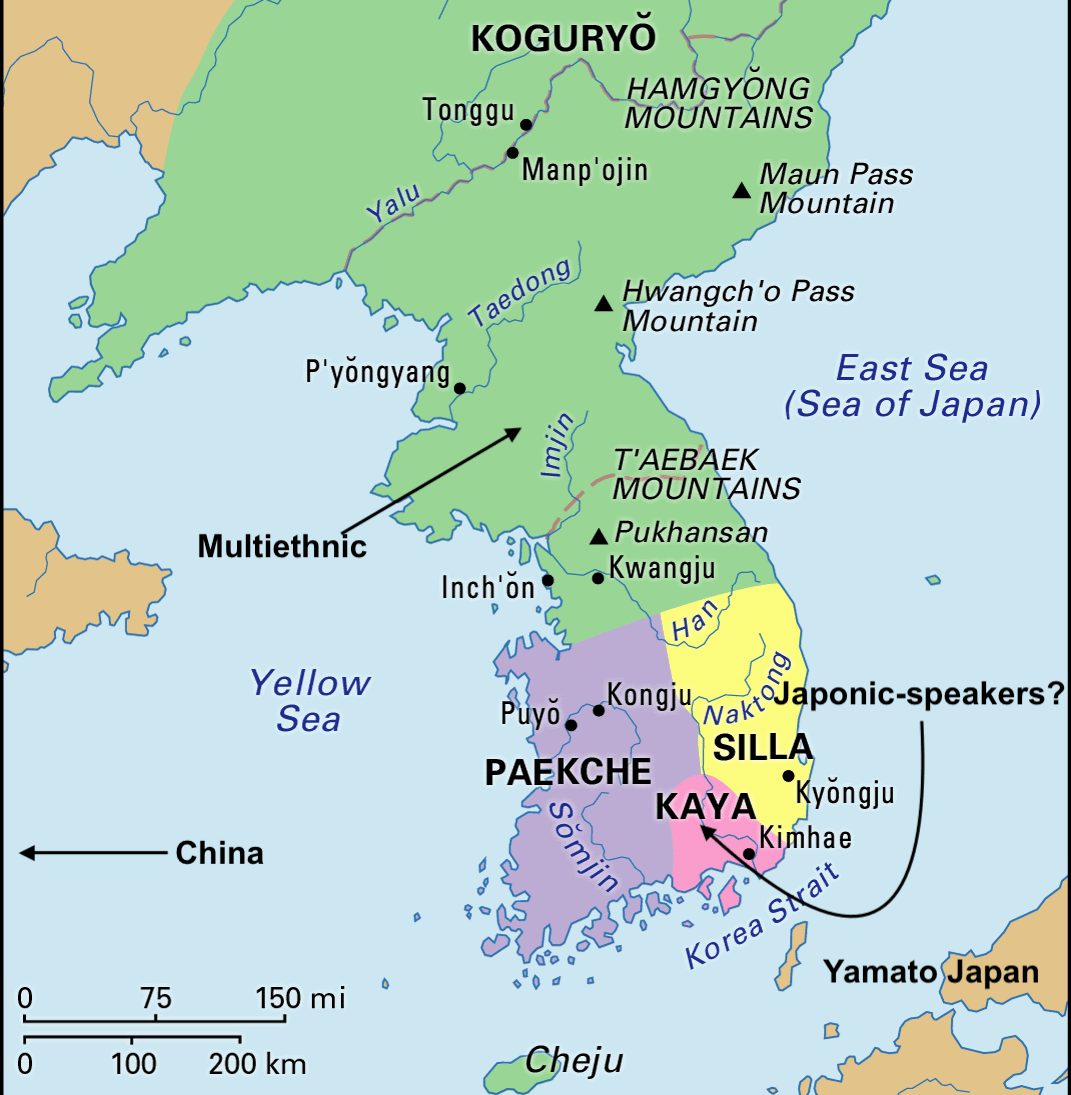

But this non-negotiable geography interacts with the fluid contingency of history. In 668 AD Silla, a domain coterminous with modern South Korea, led by its king Munmu, defeated a centuries-long rival, the Koguryo kingdom of the north. This momentously unified most of the Korean peninsula into a single state, an event which ushered in the Korean nation we still know today. Consider that by comparison, in that year Britain was divided between seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms fringed by half a dozen Celtic principalities. In continental Europe, what would become France was split into numerous duchies, as powerful local potentates relegated the seventh-century kings to ceremonial figurehead status. But except for one brief interlude of fragmentation between 892 and 936 AD in the wake of Silla’s dissolution, the Korean peninsula was destined to remain a unified state from that moment forward, not to be sundered again until 1953. The Koryo dynasty, from which the name Korea derives, reunified the peninsula in 936 once and for all, handing power in 1392 to the Choson dynasty. They ruled all the way until 1910, when the Japanese integrated Korea into the Japanese Empire, temporarily dissolving the nation-state.

The totality of Silla’s conquest fatefully closed the door on any future possibility of a peninsula with a multiplicity of ethnicities; the Korean peninsula, which in the depths of the Ice Age and down to the centuries after the birth of Christ, had been a byway of peoples from Manchuria to Japan, was instead destined to become one of the most homogeneous nations in the world.

The diverse cultural and genetic foundations of Korea predate 668 AD. But the 1,400 year continuity of a national identity across Silla, Koryo and Choson permanently interwove those threads, and goes a long way towards explaining contemporary Koreans’ shared sense of belonging, and that they are one people and one race. Most post-colonial states that arose out of the detritus of fallen modern empires are but decades old, while Korea is long past its first millennium of existence. There are, of course, other models of national identity and self-conception than Korea’s. In Germany, the preexistent nation called the state into being. In the Indian case, the administrative state created the national political identity in the 20th century. For Koreans, like their Japanese neighbors, the ethnic nation and the administrative state are inseparable, co-evolving together. To be Korean is not simply a legal writ or geographical coincidence (though both have their roles). It entails Korean ancestry and culture. Neither is Korea a legal mandate, summoned into being by will and colonial caprice (like Taiwan or many African nations).

Korea’s geographic outlines go back to the dawn of written history in northeast Asia 2,000 years ago, when Imperial Chinese chroniclers of the Han Dynasty recorded the proto-Korean tribes, the Buyeo (in central Manchuria) and Yemaek (in southern Manchuria and northern Korea), among the various barbarians brought into the fold of the Middle Kingdom. For centuries, Imperial texts referred to Manchuria and the lands that are today North Korea as the barbarian commanderies of the northeast. Silla’s political unification would smooth out the peninsula’s ethnic landscape, but the earlier diversity of peoples, some related to the modern Japanese and the Ainu of Hokkaido, others to Manchurian foragers, farmers and herds, can still be discerned in the Chinese texts, archaeological evidence and genetic record. Korean history is partly a story of those early inhabitants’ assimilation into the genetic patrimony of modern Koreans and integration into Korea’s culture and ruling class. Today Koreans share a land border with Manchuria, which until recently was ethnically very diverse, but deep in their shared past, Korea also contained multitudes, both streaming in from the great north, and moving onward to the islands of the east.

A Northeast Asian map of Korean genealogy

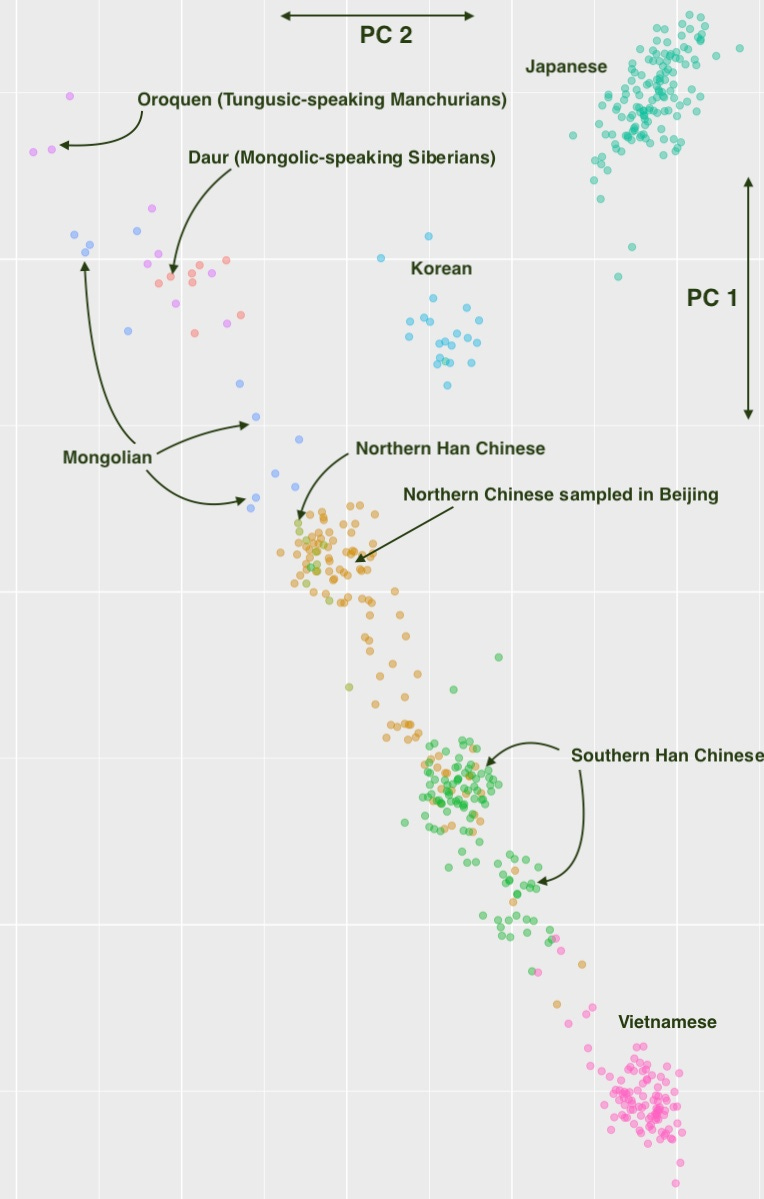

But before we further unpack the Korean genetic past, let’s look at how Koreans relate to their regional neighbors genetically today. To consider this question, I assembled a dataset composed of 20 Koreans (of South Korean heritage), 103 Han Chinese sampled in Beijing, 10 Han from northern China and 105 from southern China, as well as 132 Japanese and 9 Daur, 12 Mongols, 9 Oroqen and 99 Vietnamese. With 60,000 common markers on each typed individual, is more than enough data to run a principal component analysis (PCA) relating individuals to each other on a two-dimensional plot, and to generate a pairwise genetic distance between groups using the Fst statistic (represented by a neighbor-joining graph that visualizes the distances).

The first thing to observe about the PCA plot above is a cline running north to south in East Asian populations. The antipodes of the range are, at one end, the Daur and Oroqen, northern Manchurian and Siberian tribes respectively, and at the other, the Vietnamese, who reside in tropical Asia. The order of populations is geographically coherent: the Oroqen of Manchuria and the Daur of Siberia, Mongolians, northern Han Chinese, southern Han Chinese and the Vietnamese. But perpendicular to the primary north-south cline are the Koreans and Japanese. More precisely, Koreans are positioned between the Japanese and the non-Korean mainland populations, in particular, northern Han. Of course, this is also where they reside geographically: at the interstices of Manchuria, China and Japan.

The pairwise Fst, which summarizes genetic differences between two populations, recapitulates the pattern you see in the PCA. In the PCA, individuals mostly cluster neatly into distinct populations that correspond to the categories in the pairwise Fst. When the pairwise genetic distance is visualized on a neighbor-joining tree, the Vietnamese fall at one pole of the twig-like tree, with the Oroqen at the other. Japanese and Koreans are distinct, out on slightly longer stems branching off in quick succession, while Han populations show the expected variation between north and south (southern Han are closer to Vietnamese, northern Han to Koreans and Japanese).

The simplest demographic model which explains these genetic patterns involves serial migration and isolation by distance, dynamics which perhaps sound more complicated than they are. In essence, imagine an evolutionary phylogenetic tree and overlay it on a geographic map, adding arrows to the tips of the phylogeny, converting them into migratory vectors. Concretely, this means that when modern humans arrived ~45,000 years ago to East Asia in a single wave, some groups moved northward, enduring a population bottleneck and a subsequent split at each step. The demographic dispersion across a landscape with geographic barriers like rivers and mountains means genetic differences will accumulate between groups with shared ancestral origins. Accumulated genetic variation, represented in statistics like pairwise Fst, then is a natural outcome of human expansion and diversification that we can detect statistically, without any knowledge of precise historical details or specific events required.

The problem is that though the model is elegant, we have enough data to know it’s not true. Biology isn’t physics, historical contingency matters, and populations don’t just migrate unidirectionally forever like lost moons hurtling out of the oort cloud, branching outward and never looking back; Neolithic-era humans brought rice farming to Southeast Asia, reversing the initial anatomically modern human north-to-south direction of migration from Southeast Asia to China (ancient DNA and archaeological evidence can even date the arrival of northern agriculturalists to modern Hanoi’s environs about 4,000 years ago). At some point, China’s Yellow river basin agriculturalists expanded back westward toward the Yellow Sea coast from which their ancestors had come. At the same time, these people were expanding in the other direction, pushing into the uplands of Tibet, transforming the genetics of a region previously occupied by foragers who had earlier percolated up from Southeast Asia. Finally, Austronesians sailed out of Taiwan across Southeast Asia, and eventually across the Indian Ocean and back to Africa itself, leaving a permanent cultural and genetic legacy in Madagascar. The tips of the evolutionary tree don’t split indefinitely, repeatedly we see distant branches have been grafted back together in what were surely fraught reunions after long separation. The modern Han Chinese, who descend from the Erlitou culture of Henan that flourished 4,000 years ago, are one such fusion; scions of both northern foragers who ranged from the Yellow river plain in the west to the Liao river basin in the northeast, and southern hunter-gatherers who traversed the Yangzi basin and haunted southern China’s coastlands. The tree of humanity is really a gnarled bramble. Again and again, since we entered the age of massive genomic sample sets, we are reminded that a pinch of data is worth a pound of theory.

The Korean peninsula’s location puts it at the nexus of these various late Ice–Age populations coursing west to east and north to south. While the foragers of the Yellow river plain settled down to become farmers after the last Ice Age, to the north, in Manchuria’s forests and along its icy rivers, nomadic hunters continued to hone their skills, perfected under brutal conditions that had prevailed for 100,000 years. Further south, prehistoric foragers in the Korean peninsula developed a signature pottery style 10,000 years ago, very similar to that of contemporaneous Jomon-period artifacts in Japan. This affinity of style is almost certainly due to a shared origin among the broad network of Siberian people who had pushed eastward more than 20,000 years ago, before the peak of the last Ice Age. In Japan, these people became the ancestors of peoples known as the Ainu, but in Korea they disappeared early on in prehistory. Koreans notably were rice farmers by the time they enter the Chinese historical record 2,000 years ago, not Paleo-Siberian foragers. And rice agriculture has its origins far to the south, in the Yangzi river basin. Some historians and archaeologists have posited a seaborne migration out of the south seeding rice culture in both Korea and Japan. But the genetic and archaeological data refute this theory. Rather, a new form of pottery that spread across the peninsula around 1500 BC and arrived at the same time as rice farming derives from traditions in the Yellow and Liao river basins, pointing to an origin due west, not south.