Iran is not Iraq

Key demographic and historical data points for American observers (plus a quiz!)

A lot of American citizens currently have strong opinions about Iran and its future. But how many of them know the first thing about Iran’s past (or basic demographic, political and religious facts about its present for that matter)? What follows is a quick review of a few of the above I find most germane today. Before we start, feel free to test the state of your Iran knowledge with this quiz!

In a clip posted June 17th, 2025, Tucker Carlson asked Texas Senator Ted Cruz what Iran’s population was. Cruz refused to respond, with his defenders later objecting that this was a “gotcha” question. But Carlson’s point was that someone like Cruz, who is in a position of power and supporting American military involvement in Israel’s offensive against Iran, should know basic facts about that nation. As it happens, Iran’s population is about 90 million; more than Turkey or Germany, and far more than the 27 million Iraqis who endured US occupation starting in 2003. In addition, Iran’s area is about 2.4 times that of Cruz’s home state of Texas.

These are clearly relevant details when considering any military or diplomatic entanglement, even for the most powerful nation in the history of the world. Another crucial and germane fact is that Americans are, in many ways, a deeply parochial people who take only the most cursory interest in the rest of the world despite our nation’s legion military commitments and our complex economic entanglements. A stark illustration of this reality is that more than two decades after the Iranian Revolution major news outlets were still erroneously referring to Iran as an Arab nation.

At this point, with US intervention in the Israeli-Iranian conflict, the possibility of swift and de facto decapitation of Iran’s military leadership means that the Islamic Republic’s future will probably differ starkly from its past. With its prestige and credibility in tatters, the specter of regime change in Iran suddenly feels imminent. And alongside that eventuality comes inevitable geopolitical and economic fallout given the Islamic Republic’s various alliances and antagonisms. Change in, or the collapse of, the Middle East’s second-most populous nation of nearly 100 million (after Egypt), the world's seventh largest oil-producing nation, poised as it is at the nexus of great-power politics between the US, China and Russia, would be one of the most consequential events of the early 21st century.

The Persian civilization is ancient, but Iran the nation-state is early modern

The first mention of Persians as a people appears in 9th-century BC Assyrian annals. Before Cyrus the Great’s 6th-century BC conquests, Persians were one of innumerable Iranian tribes occupying the territories east of Mesopotamia’s venerable civilizations. By the historical period, Persia’s core territories were located in what was formerly Elam, in the southwest of the Iranian plateau. To their northwest were the Medes, who occupied modern Kurdistan, while beyond the shores of the Caspian ranged the Parthians.

Of the pre-Islamic Iranian empires, two of the most storied, that of Cyrus’ Achaemenids who dominate so much of Herodotus’ histories and the Sassanians who nearly conquered Byzantium, had their base in the Persian-speaking homeland of Fars. Because of the Persian dynasties’ prominence, the language of Fars and its cultural identity spread far and wide in the Iranian world, which before the rise of the Turks, extended to the western edge of Mongolia, and with the Scythians into the heart of Europe. Today, a form of Persian, Dari, remains one of the major languages of both Afghanistan and Central Asia broadly, and is even the native language of the Tajik people. But this is a recent historical phenomenon, driven by the ethnographic transformations Islamic-era Turkic migrations and Mongol conquests wrought.

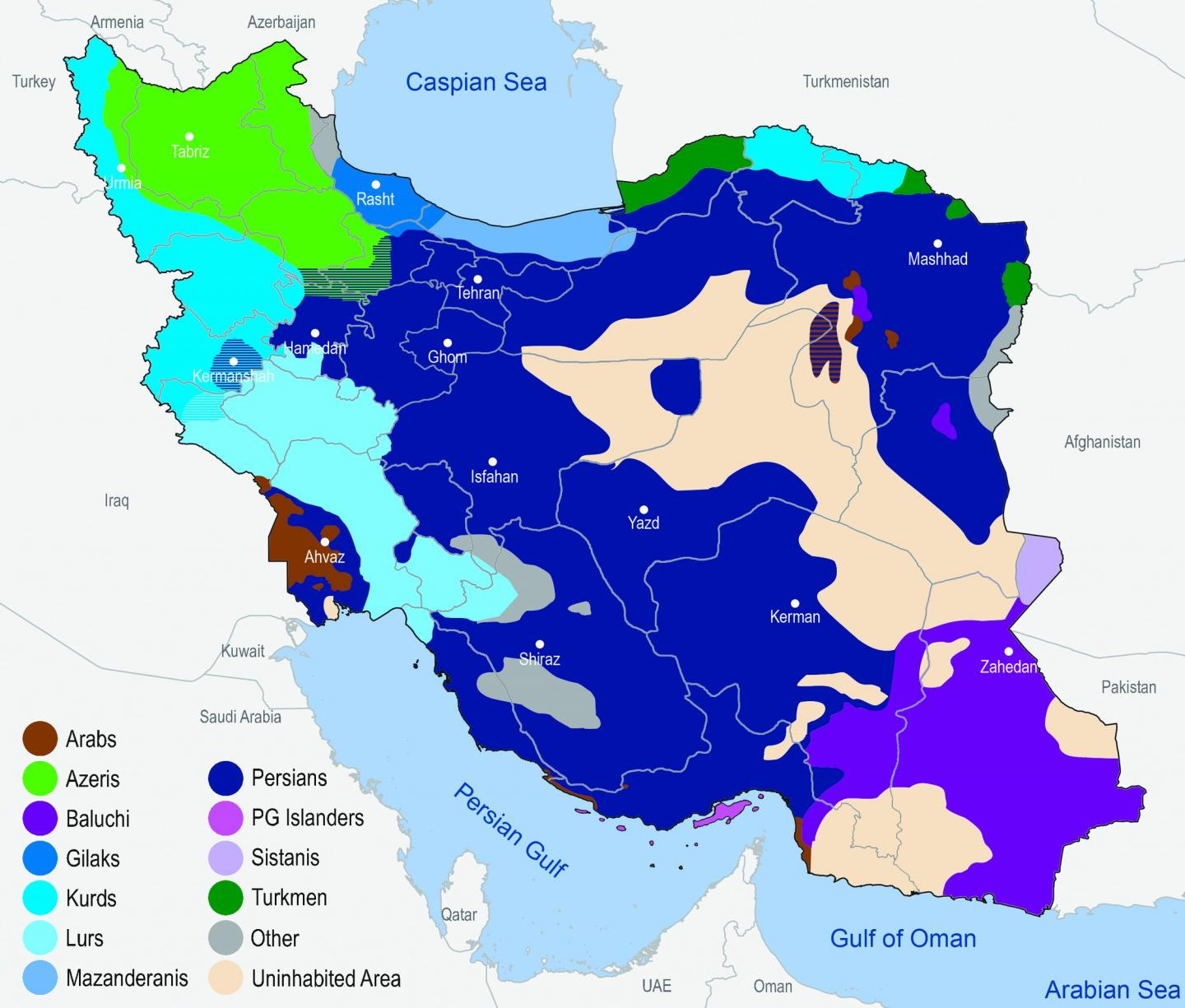

Ancient Iran's pre-Islamic diversity is still somewhat reflected in the modern nation, though. Only a slight majority of Iranian citizens are ethnic Persians. The second largest group, Turkic Azeris, at around 20%, far outnumber the population of Azeris to the north who give the nation-state of Azerbaijan its name. Despite the cultural and linguistic prominence of Persian, numerous other Iranian ethnolinguistic groups still flourish today in Iran: Kurds and Luris in the west, Gilakis and Mazanis in the north, and Baloch to the east.

This ethnolinguistic diversity superficially resembles that of Iraq, where Shia Arabs form the slight majority, ahead of large populations of Sunni Arabs and Kurds, as well as Christian Assyrians, Yezidi Kurds and Turkomans. One of the major political revolutions of modern Iraqi history has been the marginalization of the Sunni Arab ruling class in favor of the Shia Arab majority. Even though these resemblances in terms of diversity might strike some as a warning for the future of a post-regime-collapse Iran, they actually mask deep and informative differences.

Iran’s Supreme Leader, Mohammed Khamenei, has an Azeri Turk father. Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s current President, is himself Azeri. The last Shah of Iran was majority Azeri; he had an Azeri mother, as did his own father. The last Shah’s wife was also the daughter of an ethnic Azeri general. This genealogical trivia underscores the commonplace integration and investment of ethnolinguistic minorities in the current Iranian nation-state. More precisely, since 1000 AD every ruling dynasty in Iran with the exception of the Mongols and the short-lived Zands of the late 18th century has been of Turkic origin. Though Persian civilization is ancient, the broad structures and interests that dominate the modern Iranian nation-state arguably have their origin in 16th-century Safavid Iran, which was established with Shah Ismail's 1501 conquest.

Ismail and his dynasty were ancestrally of diverse origins: Kurdish, Greek, Georgian and Turkic. But in the 15th century, the Safavids, who led a Sufi order, had become assimilated into the Azeri Turkic culture of eastern Anatolia and northwest Iran. Of more enduring consequence than his ethnicity, Ismail established Shia Islam as the religion of his dynasty, and by extension, his imperial domains. This set the Safavids apart from their Ottoman Turkish rivals to the west, and later the Indian Mughals to the east, both of whom were staunchly Sunni. It also established a religious uniqueness for what had been a predominantly Sunni Iran.

The Safavids forcibly converted Iran to Shia Islam over the course of two centuries, bringing about the situation today where over 90% of the population adheres to that sect of the religion. The discrimination minority Kurds and Baloch suffer in the Islamic Republic today owes more to their Sunni identification, than to their language or ethnic identity. It is no coincidence that the Islamic Republic’s Shia-based religious nationalism seems to have had greater traction than the Pahlavi dynasty’s attempts to forge a secular Iranian nationalism along the lines of Atatürk’s Turkey. The Ottoman Empire’s collapse, the Armenian genocide and the great ethnic exchange with Greece in the 1920s, left the Republic of Turkey ethnically 75% Turkish, with only a large Kurdish minority. In contrast, an Iran that is 50-60% Persian is a nation-state that can rely upon its dominant ethnicity to furnish a unitary culture for the ruling class, while never the demographic heft to serve as the foundation for populist ethnic nationalism.

An early modern Iranian nationalism

Some states have very recent origins.This is famously true of much of Sub-Saharan Africa, where nation-states are cobbled together from various assorted ethnicities, borders arbitrarily to appease European powers locked in long-forgotten colonial rivalries. But it is also true of European nation-states like Germany and Italy, whose ethnic-national identities predated and preceded their political form that first emerged in only the 19th century. Despite cultural, linguistic, and in Germany religious (Protestant vs. Catholic) differences, no one worries that Germany and Italy are teetering on the edge of collapse, even if a millennium of political history predating the mid-19th century was fractious in both cases. The Democratic Republic of Congo may have been the creation of European colonialists, but Italy and Germany were present within the stone from which modern political movements carved them.

Probably literally because of their phonetic similarities, naive American observers might worry that Iran's collapse risks resembling that of Iraq two decades earlier. But despite these two nation-states being Middle Eastern, Muslim and multi-ethnic, they remain deeply qualitatively different, not least in their early modern histories. Europeans created Iraq from Ottoman provinces that Iranian dynasties had long threatened. It was and is artificial and novel as a political entity despite Iraq's inheritance of ancient Mesopotamia's geographical expanse. Modern Iran, in contrast, is very much the heir of Safavid Persia, with most of its ethnicities unified by a common religion that marks them off from other Muslims. Persians and Iran’s ethnic minorities genuinely share a common history across the centuries. The Islamic Republic is not like Germany or Italy. Although likewise a state that reflects a shared national ethnicity, it is perhaps more like contemporary Spain, a multiethnic polity that emerged organically from a succession of earlier states. The basis for the modern Spanish state was arguably the unification of the monarchies of Castile and Aragon under Ferdinand and Isabella, the generation before Shah Ismail conquered Iran. Like the Safavids, Spain’s Habsburg monarchs religiously unified their realms, but left its ethnic diversity intact, even if unified by a dominant Castilian language.

After the Mullahs

Revolutionary Iran arose at a particular time and place, near the tail end of the Cold War. It conceptualized itself as a “third force,” leading a Third World movement outside of the capitalist and communist blocs alike, unified by the fires of nascent Islamic revivalism. Soviet Communism is now just a memory, while the demographic engine powering political Islam’s late 20th-century revival lies in abeyance (Iran’s plummeting total fertility rate today is approaching the US’s and lower than France’s). But the Islamic Republic of Iran remains with us, a holdover of 20th-century passions, still in the long shadow of political and social forces that have long since exhausted themselves, inveighing against the “Great Satan” ad nauseum. The Supreme Leader of Iran ascended to power when George H. W. Bush was leading the US and Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union. His worldview was fundamentally shaped by the geopolitics of the 1970s. Israel’s recent attacks have exposed his regime to be riddled with Mossad operatives, suggesting the institutional apparatus is today kept running by functionaries who no longer have any faith in the system. The best analogy for the Islamic Republic is probably the Soviet Union in the Brezhnev era. Most of the populace no longer believes in the ideology, but the institutional machinery keeps moving.

If the regime falls in the near future, the most likely scenario is not the collapse of the nation-state; Iran, as an institution, has roots centuries deep. Rather, it is the chaos of 1990s Russia, when elites scrambled and jockeyed for position within an entirely novel configuration of power, and kleptocrats swarmed to divvy up the remaining spoils of the planned economy. The Iranian regime’s end is almost certainly inevitable. The question is not if, but when.

Whether or not you already took the Iran quiz before reading this piece, feel free to test the state of your Iran knowledge (again) now!

Quick thought before reading the rest, as it is nagging at me. Yes, one can call Americans parochial in not knowing much about other countries. However, I doubt that Brazilians, Swedes, Namibians, or Japanese know much about Iran either, nor about each other.

I got a 5 on the quiz and am appreciating learning many new things. I mostly knew about the language and some religious history. On we go.

Razib, thank you for this. It was fantastic. Sending this to all and sundry!